Janus and the Future of Organized Labor

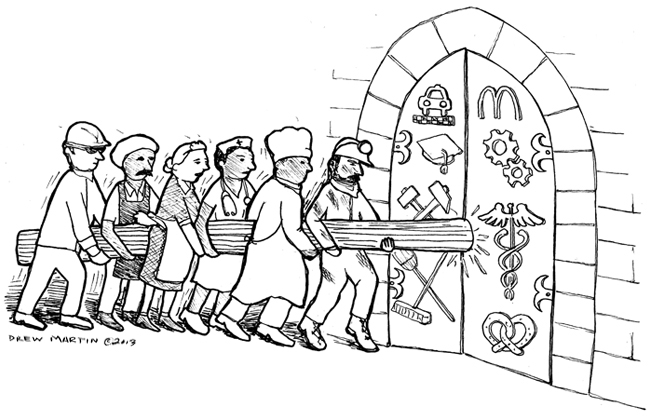

What does the Supreme Court’s five to four ruling in the case of Janus v. American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees, Council 31, Et. Al.[1]mean for the future of organized labor in the United States? As the four dissenters stressed, the court’s majority overruled a precedent that had held for more than four decades even during the Burger and Rehnquist Courts.

More remarkably the majority ignored its own preference for state sovereignty (federalism) by nullifying the authority of the separate states to determine how to manage employment relations for public workers who lack any connection to interstate commerce. And it did so by using the First Amendment in a peculiarly odd manner. The requirement that public employees who choose not to join the union that must represent them pay a fee (agency fee as it is known) that reflects the cost of such representation scarcely impinges on their free speech rights. The agency fee payer need not participate in union activities and remains free to condemn union leaders, union policies, and union actions by speech, pen, artistry, or tweet. What the ruling does, however, is to legalize or constitutionalize the act of “free-riding,” that is to enable workers to enjoy the benefits of union representation without paying the costs. Only blatant animus against trade unionism and collective action can explain the court majority’s decision.

Janus v. AFSCME resurrected an older judicial pattern of using the law and the constitution to render organization and collective action by workers ineffective. From the founding of the modern labor movement in the late nineteenth until the passage of the Norris-LaGuardia Act in 1932, union leaders had struggled unsuccessfully to liberate the labor movement from judicial interdiction. Several scholars have asserted that the political behavior of the labor movement, most notably the American Federation of Labor and its longtime president, Samuel Gompers, was primarily a response to judicial antilabor animus.[2]The Norris-LaGuardia Act by limiting the ability of courts to enjoin collective action, primarily strikes, achieved labor’s greatest desire. The New Deal added positive reinforcement by enacting legislation that guaranteed workers the right to organize and to act collectively. Beginning in 1938, the Supreme Court and most federal appeals courts in the North and West ruled quite consistently that collective action by workers was necessary to counterbalance the far greater power exercised by employers. The Supreme Court found picketing to be a protected free speech right; judges declared employers’ attacks on unions during organizing campaigns and elections to be an unfair practice because of their power to hire and fire; and in most cases, federal appeals courts upheld the rulings of the regional National Labor Relations Boards that favored unions.[3]

Protected by the Wagner Act, the decisions of the NLRB, and the rulings of federal courts, unions grew and flourished. Under the aegis of CIO unions organized the mass-production sector. When World War II brought five years of full employment and required uninterrupted production, federal authorities promoted unionism and collective bargaining as a reward for a no-strike pledge by union leaders. The government authorized union security through the union shop in mass-production industries and validated the closed shop in trades organized by highly skilled craft unionists. The labor movement came out of the war more powerful and more secure than ever before in US history, powerful and secure enough to survive the 1945-46 strike wave with membership and contracts in place. Nearly one-third of all non-farm workers then enjoyed union representation, and the Harvard labor economist Sumner Slichter declared the nation a “laboristic society.”

For the next thirty years the labor movement maintained its size, influence, and effectiveness. If unions never exceeded the one-third barrier or completely organized any sector of the economy, their influence on the economy and government remained crucial. Such major corporations as IBM, Eastman Kodak, Sears Roebuck, and Dupont remained union-free by matching union wages and fringe benefits and instituting formalized job ladders and orderly grievance procedures. Whether Democrats or Republicans held power at the national or state level, public officials dealt respectfully with labor leaders and sought their input. When and where Democrats held power labor leaders were more welcome and unions achieved many of their demands. Republicans were cooler to the wants of labor but Eisenhower or “modern” Republicanism accepted the rise of organized labor and the necessity of collective bargaining. The great exception was the Democratic South, outside of pockets of labor strength in Kentucky, Tennessee, Alabama, Louisiana, and Texas. There most Democratic state officials and US senators waged war against unionism and allied with northern and western “non-modern” Republicans.

The years from 1945 to roughly 1973, today commonly referred to as “the great contraction” saw economic inequality diminish, real wages rise steadily, standards of living improve, and contemporaries including the president of the AFL-CIO, George Meany, laud the creation of a middle-class society. Such praise for what John Kenneth Galbraith called an affluent society and others portrayed as a classless society led many labor leaders to forget about what they had once condemned as a “slave labor act,” Taft-Hartley. It also cloaked far more malign forces busily at work beneath the surface.

Ever since the New Deal reforms and shifts in judicial rulings had favored the growth of labor power, the opponents of unionism had worked ceaselessly to contain labor power.[4]By 1938 a Republican-Southern Democratic coalition in congress used its influence to undermine the NLRB and attack the CIO as a communist front. Only the war retarded their ability to leash labor power. In 1947 the conservative coalition won its first major victory with the passage of the Taft-Hartley Act overriding a presidential veto. Taft-Hartley failed to roll back or even contain labor where it had emerged unscathed from the postwar strike wave. It did succeed in thwarting the CIO’s attempt to penetrate the South. Section 14b authorized states to adopt socalled “right to work” laws that eliminated union security. In states that enacted “right to work,” nearly all in the South at first, a union-management contract no longer could require all employees to join the union although the union remained obligated by law to represent all workers. Hence the “free rider” problem. A second aspect of Taft-Hartley compounded the “free rider” problem. The act enabled employers to voice active opposition to unions and to pressure employees to vote against union representation or to decline membership if a majority voted for representation. What the NLRB and federal courts previously had declared to be unfair labor practices under the Wagner Act, Taft-Hartley sanctioned as a First Amendment free-speech right. At first employers’ ability to act openly against unionism worked primarily in Southern “right-to-work” states. Subsequently, it became an especially effective weapon against established unions as more states adopted right to work laws.[5]

Before the mid-1970s when such unionized industries as automobiles, rubber, and electrical goods followed population south and west, they brought unions with them. But capital began to replace labor (heralded in the 1960s as automation) in the mass-production sector reducing the number of automobile workers, steel workers, tire assemblers, electrical industry employees, textile workers, and even waterfront workers. As total employment declined so, too, did union membership. Fortunately for the labor movement public employee unionism surged in the 1960s and brought us to the present when 34 percent of public employees belong to unions as contrasted with fewer than six percent of private sector workers. For the last quarter of a century the largest unions have been the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees, the Service Employees’ International Union, and the allied American Federation of Teachers/National Educational Association, the unions most imperiled by Janus.

The global economic crises that began in the 1970s and recurred periodically undermined labor power everywhere. On the European continent, in Scandinavia, the British Isles, and North America, unions lost members absolutely and relatively but nowhere was the decline in membership and loss of power as great as in the United States. Once unions of highly skilled workers had been able to use their marketplace bargaining power (MBP) to monopolize the supply of labor and establish closed shops. No longer.the 1980s closed shops in the building and construction trades had become the exception. Residential building became predominately nonunion and in commercial and industrial construction major national contractors ran double-breasted operations, half union and half nonunion. Simultaneously mass-production workers lost their work-place bargaining power (WBP) as their ability to cease work at the point of production failed to paralyze transnational enterprises, which could shift production to nonunion sites domestically or to plants established overseas. The loss in union power was magnified in the United States by the growing belief among Republicans and even Democrats that in a globalized economy there was no alternative (TINA) to the market. And in a market in which workers no longer held MBP or WPB employers called the tune. In the private sector employers used a combination of their economic muscle and free-speech rights to intimidate employees, compel unions to concede essential contractual rights (concessionary bargaining), break strikes by hiring replacement workers, and oust unions from the workplace. They could also rely on federal courts to find their antiunion activities perfectly legal. Between 1968 and 2012 Republicans controlled the presidency for thirty-two years and they used their power to reshape the judiciary as an anti-union bastion. Between 2009 and 2017, Republicans stymied Obama and the Democrats from rebalancing the judiciary, and since the election of Trump, Republicans have aggressively stacked the federal courts with jurists committed to principles in which unions and labor power have no place.

Weakening unions and nearly eliminating them from the private sector served a second purpose for employers and Republicans. Ever since the reelection of Franklin Roosevelt in 1936 unions have been the most effective aggregators of Democratic votes. They have educated their members about the issues, financed the campaigns of candidates supportive of labor, and brought union members and their families to the polls. With declining memberships and shrinking treasuries, private sector unions can no longer operate as effectively in the political arena. Hence a declining share of working people have been voting for Democratic candidates and among white union members the proportion voting for Democrats has fallen.

As private sector unions lost their political muscle, public employee unions remained able to finance election campaigns, aggregate voters, and bring them to the polls. Public sector unions also enabled women and nonwhite employees (the majority of public workers) to exercise voice at the polling place as well as the work site. It was the political voice of such unions, not their workplace role, to which Janus and others like him objected; most agency shop payers simply want a free ride. The Court gave Janus what he wanted and in so doing licensed other less ideologically motivated public employees to grab a free ride. Wisconsin, once a laboratory for progressive reform, illustrates one possible result of Janus: the decimation of unionism in the public sector. Since Governor Scott Walker eliminated agency fees and dues check-off among other restrictions on union rights, Wisconsin’s public employee unions, teachers the lone exception, have lost two-thirds of their members, most of their income, and hence the ability to act effectively in the political realm.[6]Will Janus have a comparable impact on public employee unionism where it remains strong?

Some friends of labor worry that the federal courts will extend the logic of Janus to the private sector where unions still enjoy the security of the union shop. But unions in the private sector are already so decimated that they are probably beyond resurrection as currently constituted. The real questions are how best to retain union strength in the public sector and how to reorganize private sector unionism on a foundation that will enable it to grow and survive in a global economy.

There are omens of a brighter future for labor power. Clearly a gulf exists between how free market enthusiasts and judges apprehend the reality of power relations in employment and ordinary citizens do. The example of recent teacher walkouts in Oklahoma, West Virginia, Kentucky, and Arizona, right-to-work states, show that public employees can act collectively even in the absence of coordinated union leadership, that “strikers” can win the sympathy and support of fellow citizens even in deep red states, and that teachers can compel extremely conservative legislators and executives to meet many of their demands. Referenda in Ohio and more recently in Missouri demonstrate that voters, unlike legislators who are willing accomplices of conservative political action committees and lobbyists, have far more sympathy for working people and their unions. First two years ago in an Ohio referendum and on August 7, 2018 in Missouri, voters defeated right-to-work laws, in Missouri by a two to one majority.

Such omens should move union officials and organizers to spend far more time and effort with their members explaining what it is that unions do, why members should participate more actively in union affairs, and why an active membership creates a dynamic, democratic union. They must also build working relationships with community reform groups whether in political clubs, religious institutions, or private voluntary associations. Together unionists and community allies must participate politically from the local to the national level to ensure that legislators serve the interests of working people and ordinary citizens not the wealthy. As once was the case with clothing workers unions early in their history and the CIO unions in their formative and halcyon years, unionists must act in their communities as well as their workplaces.

Five years ago, in this same place I noted the words spoken in 1932 by the labor economist George Barnett prophesying a dim future for organized labor. “American trade unionism,” he said, “is slowly being limited in influence by changes which destroy the basis on which it is erected.” Those changes, he added, are likely to continue, and unless an unexpected shock to the system occurred, organized labor as then constituted had no future. His prediction, of course, proved to be far off target. That was 1932 and the New Deal and the rise of CIO followed in short order.

Given the current alignment of forces domestically and globally, will the Janus decision herald doom for labor or will dire predictions today prove as foolhardy as Barnett’s in 1932? Which is a better indicator of labor’s future: Janus or the teachers’ walkouts in Oklahoma, Kentucky, West Virginia, and Arizona and the referenda in Ohio and Missouri. I don’t know. Only a shock on the magnitude of the Great Depression of the 1930s or World War II might be powerful enough to revitalize the labor movement. Today, however, such a shock might produce greater repression than bring a New Deal for workers.

Notes

[1]Janus V. American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees, District Council 31, Et. Al., 585 U.S. ? (2018).

[2]Victoria C. Hattam, Labor Visisons and State Power: The Origins of Business Unionism, (Princeton, 1993); William E. Forbath, Law and the Shaping of the American Labor Movement, (Cambridge, MA., 1991).

[3]Some scholars interpret two Roosevelt Supreme Court decisions as indicating persistent judicial animus toward collective action. In the case of Mackay Radio [304 U.S. 333 (1938)] the court ruled that an employer was free to hire permanent replacement workers during a strike that did not involve breach of contract or an unfair labor practice. But the decision neither enjoined the right to strike nor picketing. In the Fansteel Case [306 U.S. 240 (1939)], the Court found a sit-down strike, that is worker control of company property (legal trespass), to be illegal and enabled the company to fire workers found guilty of criminal action but endorsed the NLRB’s order that Fansteel must reinstate strikers’ innocent of criminal breach.

[4]For two histories of the rise of conservative antiunionism see Kim Phillips-Fein, Invisible Hands: The Making of the Conservative Movement from the New Deal to Reagan, (New York, 2009) and for a more conspiratorial version of the same process, Nancy Maclean, Democracy in Chains: The Deep History of the Radical Right’s Stealth Plan for America, (New York, 2017).

[5]Today twenty-seven states have such laws.

[6]Walker exempted police officers and firefighters unions from the limitations on union rights because their leaders supported Republican policies.