‘One Country, One System’ under Hong Kong’s New National Security Constitution

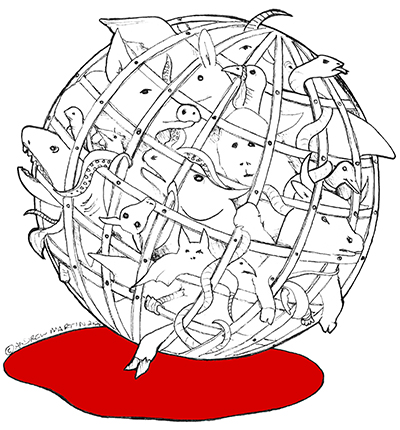

Beijing officials imposed the new National Security Law (NSL) on Hong Kong claiming that it would only reach a few bad apples, that nothing else would change. A closer look tells a different story.

In the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration Hong Kong was promised a high degree of autonomy; the rule of law in accordance with common law principles; human rights, with the full protections of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR); and democratic reform. These commitments effectively promised a liberal constitutional order, with fully half of the sixteen human rights listed relating in one form or another to freedom of expression. The continuance of the common law, with courts being independent and final was promised. All of this content was stipulated for inclusion in a basic law to be drafted. Under this “one country, two systems” formula, countries of the world were invited to recognize Hong Kong’s special status.

The 1990 Basic Law included most of this promised content, with some limitations regarding the rule of law and democratic reform.

While the courts are generally independent and final, the ultimate power to interpret the Basic Law was assigned to the National People’s Congress (NPC) Standing Committee. The NPC Standing Committee quickly took advantage of this privilege in the 1999 so called “right of abode case”—where the Standing Committee essentially overruled the decision of the Court of Final Appeals (CFA). Likewise, the NPC Standing Committee has continuously intervened to block the promised “universal suffrage” for Hong Kong.

These sticking points became the cause for a number of popular protests attracting millions of people over the years, as anxiety over growing Beijing interventions in Hong Kong grew.

Two million protesters that joined the anti-extradition protests in 2019 understood that continuing protection of the rule of law and basic freedoms in Hong Kong depended on maintaining Hong Kong’s autonomy. At the same time, they further understood that the current Chief Executive and cabinet, effectively selected by Beijing and its supporters, was not up to the task of guarding autonomy. Democratic reform to put in place a government answerable to Hong Kong became the protesters core concern.

Instead of listening to popular concerns and carrying out the promised democratic reforms Beijing officials have engaged in increased interference and repression. A complicit Hong Kong government has become the instrument of such repression.

The more indifferent Beijing is to Hong Kong concerns and the more interference and repression it administers or encourages the more resistance it receives.

The new NSL reflects Beijing’s judgement that more repression is needed, this time under direct Beijing control.

The only way this repression will be limited to a small number of bad apples is if all resistance stops. Rather than foot-dragging on democratic reform or interfering in the legal process, Beijing has effectively imposed a new constitutional order on Hong Kong.

Hong Kong’s autonomy has gone out the window in the area where it is most needed, national security.

The PRC’s national security policy generally targets China’s own people. This has long been evident in the repression of popular resistance on the mainland and in China’s peripheral communities.

In the so-called “709 crackdown” against lawyers and human rights defenders, 250 lawyers and human rights defenders were initially charged with “subversion of state power” or “picking quarrels and provoking trouble.”

The spirit of such containment is best reflected in China’s famous “Document 9,” a communist party directive which forbids promoting—including teaching—topics like constitutionalism, separation of powers and western notions of human rights.

Many in the academy wonder if the NSL now represents a Hong Kong version of Document 9. Mainland officials have particularly attacked the separation of powers inherent under Hong Kong’s common law tradition.

The NSL clearly undermines autonomy in this sensitive national security area, providing for the creation of a local Committee on the Safeguarding of National Security (hereinafter the “NSL Committee) and an Office for Safeguarding National Security (hereinafter the “NSL Office).

The NSL Committee is chaired by Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam and made up of leading cabinet and law enforcement officials. It is answerable to the Central People’s Government (CPG) and advised by a top mainland official in Hong Kong. The National Security Adviser, already appointed, is Luo Huining, the head of the local Beijing Liaison Office in Hong Kong. Given the NSL Committee’s subordination to the CPG, we might assume that it would ignore the advice given at its peril.

The NSL Committee directs all local staff in national security operations. These staff include special units set up in both the police and the Department of Justice.

The NSL Office is fully staffed with mainland state and public security officers. Its duties include “overseeing, guiding, coordinating with, and providing support to the region in the performance of its duties” respecting national security. It engages in intelligence gathering and handling cases concerning national security. Its activities are secret, effectively being secret police.

Beyond autonomy, large areas of the rule of law also go out the window. Even though NSL Article 4 promises continued protection of the full catalogue of human rights under the ICCPR, the NSL contains many restrictions that undermine the achievement of this purpose.

As a national law, later in time and more specific than the Basic Law (also a national law) it would appear to override the Basic Law where there is conflict—as specified in China’s Legislation Law. It therefore seems highly doubtful that a Hong Kong court could declare any article of the NSL invalid, as a violation of Basic Law guarantees.

The obstacles to otherwise overseeing NSL enforcement efforts are formidable.

The NSL Committee’s actions are secret and not subject to judicial review. The NSL Office, in carrying out its duties is not subject to local jurisdiction.

While ordinarily prosecutions should be carried out in the local courts, subject to normal Hong Kong legal process, the NSL provides avenues around local procedural protections. Article 42 appears to impose a presumption against bail, providing, “No bail shall be granted to a criminal suspect or defendant unless the judge has sufficient grounds for believing that the criminal suspect of defendant will not continue to commit acts endangering national security.”

The Secretary for Justice can direct that the case not be tried by a jury, in which case a three-judge panel will become the trier of fact. Such proceedings can also be closed to the media and the public, with only the judgment issued in open court.

In a clear indication of mainland official distrust of Hong Kong judges, only judges on a special list chosen by the Chief Executive of Hong Kong are empowered to hear NSL cases. Such judges are appointed to this list on a one-year basis and can be removed from the list if he or she “makes a statement or behaves in any manner endangering national security.” Since judges are normally bound by ethical restraints it would seems such endangering statements would relate to their rulings in NSL cases.

Access to justice may be further impaired under new regulation issued by the NSL Committee whereby the police, in carrying out their duties, may in certain investigations conduct warrantless searches or surveillance.

Worst of all, when it comes to procedural justice, the NSL Office may take over a case entirely, with the Chief Executive’s approval, and transfer it to the mainland for trial under mainland criminal procedures. Mainland China is not subject to the ICCPR and mainland trials in national security cases will not adhere to Hong Kong’s common law standards for criminal justice.

The NSL problems are not just procedural and stretch beyond the degrading of autonomy. The four crimes, all with serious penalties from three years to life in prison are all vaguely defined. Secession expressly does not require “force or threat of force.” Subversion can occur when merely “attacking or damaging” government premises. Terrorism might include “dangerous activities which seriously jeopardise public health, safety or security.” Collusion includes such things as seeking foreign sanctions or provoking hatred by unlawful means. All of these crimes include charges for inciting, aiding or abetting.

As some early cases suggest, collusion may often be connected with secession. In Hong Kong this appears to target the many youth groups who use localist language of identity.

The early August arrest of Jimmy Lai and nine others appears to relate to support for overseas organizations with slogans such as “stand with Hong Kong,” which have allegedly encouraged pressure on China to honor its Hong Kong commitments.

This sort of activity is the standard work of human rights advocacy. It falls far short of the sort of imminent national security threat required in relation to freedom of expression by international standards.

That the NSL reaches the prohibited behavior worldwide, by Hong Kong residents and non-residents alike, has raised global concern. In one case, the Hong Kong special police unit has issued an arrest warrant for an American citizen, Samuel Chu, in respect of his lobbying of the U.S. government to put pressure on China regarding its commitments to Hong Kong.

If we include the various provisions for overseeing national security in schools, universities and even foreign media organizations, then the threat to freedom of expression is breathtaking. The Hong Kong Secretary for Education has even called on schools to ban unofficial “anthem” adopted by Hongkongers, Glory to Hong Kong.

As a further treat to free speech, several legislators were disqualified from running for office merely for criticizing the NSL.

Taken as whole, the NSL has surely instituted a new constitutional order. Hong Kong now effectively has a national security constitution.

In the midst of the furor over the NSL, Beijing has accused foreign governments, who criticize the NSL, of improper foreign interference. Since Beijing originally invited foreign countries to recognize Hong Kong’s special status based on its commitments in the Basic Law, such foreign response criticisms and expressions of concern appear justified.

Michael C. Davis, a former law professor at the University of Hong Kong, is a Senior Research Scholar at the Weatherhead East Asia Institute at Columbia University and a Global Fellow at the Woodrow Wilson International Center in Washington, DC.