The New Left and the Marxian Legacy: Encounters in the U.S., France and Germany

In the mid-1960s, as the Cold War seemed frozen into place after the Soviet repression of the Hungarian uprising in 1956, and the stalemate that defused the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, the spirit of a “New Left” began to emerge in the West.

Although encouraged by events in the Third World, its common denominator was the idea that the misunderstood (or misused) work of Karl Marx must have offered a theory that both explained the discontent with the present among a new generation of youth and could also offer them guidelines for future action. At once personal and social, critical and political, this expectation was encouraged by publications of the writings of the young Marx as well as the discovery of non-orthodox theorists and political activists whose critical work had been ignored or suppressed by Soviet dominated communist parties. These theories represented an “unknown dimension”[1]that became the object of vigorous debate in the 1960s and early 1970s. The searching candle burned bright for a decade before it flamed out.

Meanwhile, the revolutionary spirit that Marx liked to call the “old mole” had grubbed its way underneath the Iron Curtain; the multi-faceted movement of civil society against the repressive states anchored to the Soviet bloc brought finally the fall of communism. But the critical spirit was too weak, economic need weighed too heavy, and the spirit of utopia waxed. It seemed as if there were nothing to inherit from the past. As in the 1960s, the critical spirit of the young Marx, the critical philosopher searching for his path, can suggest a reason to persevere. In a “Preliminary Note” to his doctoral dissertation, Marx justified his refusal to compromise with existing conditions by invoking the example of Themistocles who, “when Athens was threatened with devastation, convinced the Athenians to take to the sea in order to found a new Athens on another element.”[2] This was not yet an anticipation of Marx’s turn away from philosophy to political economy. Like the New Left, Marx was trying to articulate the grounds of a critique of a present that he considered “beneath contempt” in order to hold open the political future.

I will use this idea of a New Left to conceptualize the underlying unity of diverse political experiences during the past half century. Although Marx is not the direct object of my reconstruction, his specter is a recurring presence at those “nodal points” where the imperative to move to “another element” becomes apparent. These are moments when the spirit that has animated a movement can advance no further; it is faced with new obstacles, which may be self-created. I will analyze from a participant’s perspective the development of the New Left in the U.S., France and West Germany as it tried to articulate what I call the “unknown dimension” of Marx’s theoretical project.

I. Innocent Beginnings

As the Civil Rights movement spread, and more rapidly as it merged with protests against the Vietnam war, it was necessary to propose a political theory to explain both the conditions against which protest was raised, and the future projects and goals of the movement. This two-sided imperative, analyzing critically the present while opening a future horizon could not be realized by a single academic discipline such as sociology or economics; critical analysis of the present coupled with a normative reflection on the positive possibilities latent within it has always been the domain of political philosophy. The dominant mode of analytic philosophy in most major Anglo-Saxon philosophy departments dismissed concern with history or politics as speculative.[3] It was (barely) legitimate to appeal to the existentialist voluntarism of Jean-Paul Sartre; but the French philosopher’s demonstration that Marxism is “the unsurpassable horizon of our times,” elaborated in the 800 plus pages of his Critique of Dialectical Reason (1960) was not translated until 1976. It was (barely) more acceptable to turn to Husserl’s or Heidegger’s phenomenological concept of the life-world (and the recognition of lived-experience as a “horizon”), although the latter had been discredited politically and only the first volume of Husserl’s Ideashad been translated. However interested, most Americans did not have the linguistic competence to pursue this path.

Marxism in the adulterated forms of dialectical materialism was not a serious philosophical or political alternative. After the ravages of McCarthyism, there was no political (or commercial editorial) market for it. I bought my first copies of Capitalin the summer of 1965 from an old communist who would drive from San Antonio to the University of Texas in Austin with a trunk full of literature from Progress Publishers in Moscow. Party control of Marx’s writings was maintained so far as possible by its American affiliate, International Publishers. I experience their desire for control when they interviewed me on Christmas Eve of 1970 about a possible translation of the young Marx. The meeting came to a rapid end when I suggested that I would of course add explanatory notes to explain difficult passages.[4] The only option seemed to be to create a new mode of publication. The first step in that direction was taken when the New Left recognized that it was not the first new left, and that America had not always been a status quo society. This insight gave rise to the development of “history from below,” which was pursued in the mimeographed pages of the student-run journal, Radical America. Although the initiative came from historians (led by Paul Buhle), the pages of this journal were open to philosophical and critical theory as well. The young Marx found a place here, as did contemporary French theory, as did I.[5]

Of the politically engaged theoretical journals that emerged in the late 1960s Telos was the most provocative. After two issues as the “official bi-yearly publication of the Graduate Philosophy Association” at Buffalo, the journal defined itself as “definitely outsidethe mainstream” in issues 3 to 5 (Spring 1969-Spring 1970); a year later, it called itself more modestly an “international interdisciplinary quarterly,” but its radical editors defined themselves as “revolutionary” rather than simply “radical.” in numbers 10 and 12 (winter 1971 and Summer 1972). The labels are unimportant; the fact that the journal remained resolutely international influenced more strongly its future. Its history was marked by disagreement, dissent and ruptures, each justified by appeal to the practical implications of theoretical choices.[6] Intellectual, political and personal issues both bound together and separated the editors.

Speaking for myself, I joined the editorial board in the Fall of 1970 with issue 6 (a 360 page summum that contained among contributions by the editors, as well as essays and translations by Tran Duc Thâo on the “Hegelian dialectic,” Maurice Merleau-Ponty on “Western Marxism,” Georg Lukács on the “Dialectics of Labor” and Agnes Heller on “The Marxian Theory of Revolution.”[7]). The editors of Telos were fully embarked on a voyage of initiation that began to with two issues consecrated to the repressed works of Georg Lukács (numbers 10 and 11, 1971-2). Looking back today at the old volumes, I am a bit astonished by the breadth and depth of their themes. They present a juxtaposition of the stages of rediscovery of critical Marxism with a concern for French political debate (André Gorz and Serge Mallet, as well as the challenge of structuralism to the Hegel-inspired critical theories), as well as critical readings of Eastern European attempts to save what was critical in classical Marxism (in the theories of the Budapest School, or the work of the Czech philosopher Karel Kosik, as well as the banned Yugoslav Praxisphilosophers). Hard-to-place figures like Karl Korsch, Ernst Bloch or the Dutch astronomer and founding spirit of the Council Communists, Anton Pannekoek, found themselves alive again in the pages of Telos. The diversity of the contributions reflects the avid curiosity of the authors. But this eager openness and free floating critical spirit did not last.

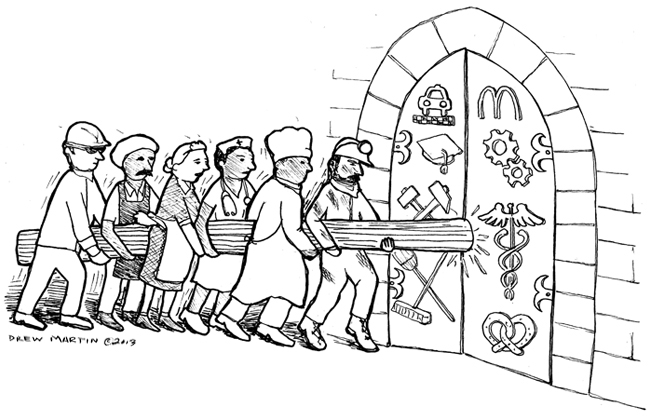

I left Telos officially with issue 36 (Summer, 1978), after a series of critical exchanges among the editors that began already in 1974. The intellectual climate had changed with the political normalization. During the first years ofTelos,the Vietnam war continued, as did opposition to its senseless pursuit. The rapid self-initiation into the varieties of Marxist theory and the nuances of its practice seemed all the more urgent; working with texts in French and German, providing translations and commentaries on them, the editors had remained, as they promised, “definitely outsidethe mainstream.” In the uncertain political conditions created by imperial war, colonial adventure, and the fight against racial discrimination at home, the serious work of theory was felt to be a kind of praxis. But a problem arose from the identification of Marx’s theory as the banner of resistance and the key needed to open the door to a revolution that seemed ever more imperative as repression at home increased. Repression had to be met with resistance, on all fronts, including that of theory.[8]But resistance could become stubborn and dogmatic, pledging allegiance to the flag of Marxism at the cost of creating a climate that discouraged critical thinking.

An expression of this uncritical Marxist dogmatism led me to finally leave Telos. The editors were unwilling to publish the essays by Claude Lefort and Cornelius Castoriadis that I had proposed for translation. It was apparent that their explicit critiques of Marx were too much to accept in a journal that felt the pressured to hold high the partisan banner; to criticize Marx could seem to provide ammunition to the enemy (as if we critical theorists were perceived at all by that enemy). I prevailed ultimately, writing introductions to their essays published in successive issues in the winter 1974 and spring 1975 issues (numbers 22 and 23).[9] The experience left a bitter residue; my concern was not to defend the Marxist faith but to recover the spirit of the New Left. From this perspective Telos had become what I called a “meta” forum, publishing analyses or revised interpretations of second generation representatives of that “unknown dimension” whose aura had drawn the original editors to the project. Commentary on commentaries gave me the feeling that the journal was no longer “definitively outside” of the establishment. I managed to arrange publication of some contributions, mainly on French themes, but the editorial trains were on different tracks; careers could be made, although it would be unfair to confuse fidelity to dogma with opportunism. In spite of the journal’s cosmopolitanism and the diversity of its contributions—some resuscitating forgotten Marxian radicals such as Karl Korsch (e.g., issue 26, Winter 1975), others joining theoretical analysis with contemporary politics (e.g., issue 16 which brought together Marcuse’s 1930 essay on the concept of labor with André Gorz’s analysis of the division of labor in the modern factory), the reheated dinner no longer satisfied my imagination.[10]

My story had not ended. The motivation that had brought me to Telosled me to return to the journal as “Notes” editor with issue 58 (1983). I wanted to take account of new phenomena that were appearing, particularly but not only in East-Central Europe. It seemed necessary to stress their novelty, rather than to insert them into an already valid theoretical framework. The journal had begun to publish originalessays and translations from Eastern Europe where the challenge of Polish Solidarnosctrade union to the totalitarian state was relayed by oppositional intellectuals in Hungary and elsewhere. Telosbenefitted from the presence in New York of two Hungarian students of Lukács, Agnes Heller and Ferenc Feher, as well as the editorial input of Andrew Arato, a native Hungarian. There was excitement in the West as well, as the idea of the autonomy of civil society began to take hold. This seemed to confirm much of what Lefort and Castoriadis had asserted in their essays published earlier, as well as in their articles reprinted by Teloson the twentieth anniversary of the Hungarian revolution (issue 29, Fall 1976). I took responsibility for the “Notes” section of the journal because the times did not seem right for a new grand theory. A politics based on the autonomy of civil society had to remain alert to signs of the new rather than rely on old truths.[11].

As it happened, I soon found myself in the modest minority of editors; the proponents of grand theory came increasingly to the fore. I left the journal once again with issue 71, in 1987. I was not surprised to find that issue 72 was devoted to the work of Carl Schmitt; I should have seen it coming. My misperception resulted in part from the fact that I, along with Lefort and Castoriadis, distinguish between “the political” which defines the framework within which the legitimate struggle for power can take place and political action itself. Already in 1974 I had titled an article on Habermas “A Politics in Search of the Political,” and a decade later, in the context of the East European emergence of civil society, I analyzed what I saw as “The Return of the Political” which I suggested could make possible “A Political Theory for Marxism.”[12] My conception of the “political” differed radically from Schmitt’s conservative-decisionist theory, which came to dominate the journal. Telos has continued to publish, apparently remaining on the conservative path accompanied by traditionalist overtones that I am unable to understand.

II. The French Connection

Another option open to a would-be New Leftist in the 1960s could be found in France. As a country where the Communist Party had won a quarter of the vote in the post-war years, France seemed to prove the cultural legitimacy of Marxist theory. What is more, it was also the home of critics of Marx who considered themselves to be leftists, many of whom were philosophers. The most famous was the “existentialist,” Jean-Paul Sartre (whose gesture in refusing the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1964 because it implied acceptance of “bourgeois” values pleased many a young iconoclast).[13] An American had a further reason to chose France: its revolutionary tradition appealed to equality, whereas the American tradition of 1776 stressed individual liberty. Indeed, the Civil Rights Movement was demanding protection above all for individual rights rather than seek a cross-racial class struggle. That choice was not a tactical error; but it had to be understood as only the first stage toward revolutionary change.

France between 1966 and 1968 provided both an initiation to Marx and a critique of Marxism. At the Communist Party’s annualFête de l’Humanité, I was refused free entry although I explained that I was a comrade getting by on scholarship. Later, at a demonstration against the Vietnam war, a speaker from the Party demonstrated the justice of the anti-war cause while showing its place in a long historical chain; at the end of his discourse, as the public applauded, he joined them, suggesting that he was not expressing his opinion but spoke the truth of historical necessity. A similar Marxist conviction animated the Trotskyist opponents of the communists. Those who attended their (smaller, semi-public) meetings had to sign-in under a pseudonym, increasing the thrill and sense of the exclusivity of participation.[14] The theoretical justification of this practice was that the revolution could come at any time, and that without an organized and knowledgeable leadership to give direction to the working class could fail, or be stolen and deformed (as was said to have been the case in the Soviet Union). The point was well taken; theory was necessary. I moved into the dormitory at Nanterre where I spent a good part of the day reading Marx’s Capital while watching a nasty yellow smoke rise from the tin shacks of the neighboring bidonville.

There are experiences offer lessons that could not be drawn from books. The principal theoretical challenge that occupied me was to identify the working class that was assumed to be the agent of revolution.[15] Had the capitalist economy brought into being a “new working class,” as several theorists whom I came to identify with the New Left claimed. Among them were Serge Mallet, whose analysis of La nouvelle classe ouvrièreappearedin 1963; André Gorz published Stratégie ouvrière et néo-capitalismin 1964; and Daniel Mothé published Militant chez Renaut in 1965.[16] Mallet had been a functionary of the Communist Party; after he quit the party when it proved incapable of understanding or resisting the new Gaullist regime that came to power in 1958, his research was funded in part by a grant from Jean-Paul Sartre. At the time, Gorz was a journalist at the weekly magazine, Le Nouvel Observateur,author of the existentialist analysis of alienation in Le Traître, and a member of the editorial committee of Sartre’s journal, Les Temps Modernes.[17] Mothé, whom I came to know at the journal Esprit, had been a line-worker at the huge Renaut automobile plant at Billancourt while a member of the group Socialisme ou Barbarie, insisted on the capacity for self-organization on the part of workers without the need for a political party to show them the way. What the three political thinkers shared was a welcoming eye for the new. Needless to say, all three were eager participants in the “events” of May 1968.

I followed here the French usage in talking about May 1968 as “events.” What crystallized in the “March 22nd Movement” at Nanterre before spreading and spiraling across France (and abroad) had little to do with Marx. In retrospect, the losers on the left were what I call the Marxists: the Maoists, who insisted that real revolution could not be led by students; logically consistent, their followers ignored the campuses and went instead to the working class suburbs, where they found no echo; and the Communist Party (and its trade unions) who did their best to restrain the unexpected movement that they could not master. For my part, at Nanterre, I had the feeling during the pre-May meetings on campus that I was back at a New Left gathering in the States. It was as if the over-politicized students who, in earlier meetings I had attended, had harangued one another about the need to support the “peasants and workers of X” rather than the “workers and peasants of X” were now speaking English[18] The price I paid for this comfort was in a way paradoxical; I had come to France to find a theory that could make political sense of my New Left experience not to confirm it, now in a new language.

A first reflection after the experience of May ’68 led me back to Marx. What was the relation between the philosophical explorations of the young Hegelian whose analysis of capitalism explored the diverse ramifications of alienation (as both Entfremdungand as Entäusserung) and the author of Capital whose three thick tomes demonstrating the internal contradictions and necessary breakdown of capitalism I had been studying in that dormitory at Nanterre? The ebbing of the spirit of May seemed to lend weight to the structuralist arguments of Louis Althusser, who drew a sharp line between Marx’s “scientific” work and his youthful philosophical explorations. The simultaneous publication in 1965 of his Pour Marxand the two collaborative volumes of Lire le Capital seemed to offer a material foundation for the New Left experience that I had come to France to find. The political price to be paid, however, was not realized by most at the time.[19] The all-encompassing denunciation of ideology in the name of “science” left no room for subjectivity characteristic of the new left or the May movement; the result eliminated the pole of negativity characteristic of the dialectic. I tried to avoid this dead end in my revised doctoral dissertation that proposed an analysis of The Development of the Marxian Dialectic[20]. The qualifier “Marxian” (rather than the substantive “Marxist”) was meant to show that his turn to political economy was based on the dialectical elaboration of Marx’s youthful philosophical insights.

Other questions raised by the experience of May ’68 led me back to the existential Marxism of Sartre. At the “First International Telos Conference” in October 1970, I proposed an analysis of “Existentialism and Marxism.”[21] I was led to this theme by a slim volume titled Ces idées qui ont ébranlé la France. Nanterre Novembre 1967-juin 1968[22]. The author uses categories developed in Sartre’s Critique of Dialectical Reasonto reconstruct the tumultuous emergence on one campus of a revolt that “shook the nation.” The author concludes on a note of what can be called pessimistic optimism. Sartre had tried to explain the transformation what he called serial and external relations among alienated individuals through a movement that transforms them into a “group-in-fusion” through which passive participants become for a moment fused as active members of a collective subject. Sartre recognizes that by its very existential nature the fused group is unstable; it has to seek means to conserve its unity. The only possible solution to this political problem seems to demand that the existentialist cedes his subjectivity to objective knowledge of the Party. Sartre is more subtle in the Critiquethan he had been earlier; appealing to the history of the French revolution, he introduces first the idea of an “oath” by which the fused group binds itself. The words appear to be powerless inn the face of the hard, existential reality of “scarcity” that Sartre calls the “practico-inert.” The oath must then be enforced, ultimately by Terror, itself enforced by a leader who functions as an external “totalizing Third” whose description at times recalls Stalin, or the communist Party. This troubling political implication of this attempt to join existentialism and Marxism may be one reason that Sartre never completed the promised second volume of his Critique.

One last French encounter deserves mention here. As is well-known, French intellectuals of a leftist bent often express their allegiances, or their protests, by signing petitions that are reproduced in journals read by a wider public. In the late winter of 1968, I attended the presentation of a petition against the war in Vietnam by a group that included among others, Sartre. Afterwards, I wrote a short paper for the journal Esprit reflecting on “Les intellectuels français et nous.”[23] My point was that words are cheap; there are actions to be undertaken. I didn’t mention the fact that I had been working with a network formerly active against the French war in Algeria that was now involved in helping American deserters. One of the other participants at the press conference was Pierre Vidal-Naquet, who contacted his friends at Esprit to find out who I was. We met; I arranged for him to meet with some of the Americans; we became friends. A few years later, when I was wanted to have a chapter on Socialisme ou Barbariefor The Unknown Dimension, Vidal-Naquet, an engaged intellectual who never joined a political party, arranged for me to meet Lefort, which in turn led to my meeting Castoriadis. Reflecting on the experience, I have concluded that my activist resentment of the intellectual who signs was based on a misunderstanding of the solidarity of critical individuals who think for themselves.

III. The German Path: From Phenomenology to Critical Theory

The Contributions to a New Marxismpublished by Telos included Paul Piccone’s proposal for the elaboration of a “Phenomenological Marxism.” The editor in chief was summarizing his vision of the path followed by the early Telos. Enzo Paci, the radical Italian phenomenologist, had developed a critique of the pretension to scientific objectivity on Husserl’s posthumously published Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology.[24] Paci tries to demonstrate that the foundation of this vision is an alienation from the lived-world whose effect is the further reproduction of alienated relations that make the human quest for meaningful experience impossible. It took only a short step for Piccone and the early editors to recognize that the implacable logic of capitalism is a manifestation of a similar alienation. This interrelation became clear when Telospublished in the same issue, translations of Herbert Marcuse’s 1928 “Contributions to a Phenomenology of Historical Materialism” along with Husserl’s account of “Universal Teleology.”[25]Capping that issue was Piccone’s essay on “Lukács’ History and Class ConsciousnessHalf a Century Later” which made the integration of phenomenology and Marxism explicit. Despite its sad political fate, Piccone was certain that Lukács’ book had still the potential to reclaim its explosive impact.

Although I was not yet involved with Telos, two brief “Notes” that appeared in the same issue dealt with events in which I had participated, making me more receptive to the journal. One note affirmed Telos’outsider perspectivethrough a biting report on the American Philosophical Association’s winter meeting (at New York’s Waldorf Astoria hotel!). Intellectually irrelevant, the big name figures of the academic world were denounced for having mobilized their fellows against a condemnation of the Vietnam war, while their job-seeking graduate students were consigned to a Kafkaesque maze on the 18thfloor where they competed for interviews. The other Note, also critical, commented on an international phenomenological colloquium in Schwäbish Hall, West Germany, which was said to have placed insufficient emphasis on the importance of the life-world. The exception was said to be the synthetic conclusion presented by Paul Ricoeur.[26]

The political difference between a phenomenological foundation for radical politics and Althusser’s structuralism is striking. The French Marxist was criticizing a bourgeois subjectivism that supposedly led to a philosophical idealism that separated theory from its practical implications. The task of structural logic, as Althusser thought he had found it in Capital, was to demonstrate the material condition of possibility of radical change by overcoming the separation of theory and praxis. The difficulty is that structuralism (like dogmatic materialism) leaves no place for the inter-subjectivity that constitutes meaning in the life-world. contrast, the phenomenological insistence on the primacy of the life-world led to the recognition that lived experience is inseparably the foundation of the world of the subject and the condition of its possible objectification in positive science. Neither can exist or be understood apart from the other. Phenomenology avoids the either/or of materialism and idealism; in this way it overcomes what Lukács called “reification” and the young Marx denounced as “alienation.” While this reading of phenomenology can veer toward a Hegelian-Marxist theory, the ideas of a life-world and the lived-experience within it were in fact fundamental for the emerging New Left.[27]

The similar political reflexes among New Leftists did not obviate the differences in their cultural and historical background. The German New Left experience was at first affected by the fact that the Social Democratic Party (SPD)—the lineal heir of the party of Marx and Engels!—had decided at its Bad Godesberg Conference in 1959 to abandon its self-understanding as a class based party of revolution. Because it had opted to become a reformist “peoples’ party,” the SPD no longer referred to Marxism as its guiding philosophy. In the following years, as its youth organization, the Sozialistische Deutsche Studentenbund (SDS), began to radicalize in ways that resembled the experience of their American counterparts in the other SDS[28], its leaders were tempted to return to the Marxism and class theory that the reformists had rejected. One important difference between the two movements was that the Germans had access to the original texts of Marx.[29] This was a temptation that could lead to scholastic debates about text interpretation, or to dogmatic claims to know better than the simple participants. In both cases, it turned attention away from the creativity of practical interventions by the young militants that were rapidly changing the inherited mandarin culture.

The German New Left was generally more bookish than most of its American cousins. Its members were also more concerned with the past, which the reconstructed Western nation did its best to forget. In the case of the Frankfurt School, Horkheimer and Adorno no longer identified themselves with Marxism as Critical Theory; Horkheimer refused to republish the yearly volumes of the Zeitschrift für Sozialforschungthat were published from exile between 1932 and 1941. Horkheimer played an administrative academic role while still teaching at Frankfurt, while Adorno was widely known for his cultural interventions on the radio. But their reputations had preceded them. Radical students began to publish pirate editions photocopied from the original texts, glued together on cheap paper, bound with thin red cover pages, as a sort of Samizdat! Among those that I purchased at the Karl Marx Buchhandlung in Frankfurt between 1968 and 1970 are the complete edition of the Zeitschrift, and three volumes of Horkheimer’s essays titled Kritische Theorie der Gesellschaft, as well as the Dialektik der Aufklärungand Authorität und Familie. Two other small volumes by Horkheimer also remain on my shelves: the Anfänge der bürgerlichen Geschichtsphilosophieand three essays from his most radical period, 1939-41, published under the title, Autoritärer Staat[30]

Whether their books concerned Marx or the Frankfurt School, the German New Left was a generation of readers. In a way, that was true of all of the New Lefts. One cultural trait that marked the Germans was the idea of a life-world that must be protected against instrumentalization. The refusal to treat what should be an end in itself as a means to something else, be it capitalist domination or a science acquired at the cost of one’s humanity, is a tradition that goes back to the German Enlightenment and to Kant. At their most pessimistic moments, Adorno and Horkheimer constructed an historical- ontological “dialectic of enlightenment” that arises when reason turns on itself leaving the way clear for domination by unreason, as it had after 1933. Horkheimer had allowed himself a somewhat less fatalistic, more political interpretation of the historical moment in The Eclipse of Reason(1947). Significantly, its German edition twenty years later, published as Zur kritik der instrumentellen Vernunft, was more than twice its size. Its final essay, which dates from 1965, reaffirms the goals of Critical Theory—the critique of the existing order—with the caveatthat the “threats to freedom” that werethe subject of his original essay have changed.

The new German radicals wanted not only to criticize the existing world; they wanted to change it. Seeking their way, they tried to return to the origins of critical theory. They read Horkheimer’s path breaking essay “Traditional and Critical Theory” and—having read Marcuse’s One-Dimensional Man—they eagerly read the exchange between Horkheimer and Marcuse titled “Philosophy and Critical Theory.”[31] Then they went back still further, to Marx, especially the young Marx. What they found gave them a deeper sense to critical theory.

Those who did their reading of the young Marx could not fail to be struck in particular by two passages. The first, in the “Exchange of Letters” (among Marx, Ruge and Feuerbach) that introduced the Deutsch-Französischen Jahrbücher, insists: that “We do not face the world in doctrinaire fashion, declaring ‘Here is the truth, kneel here!’…We do not tell the world, ‘Cease your struggles, they are stupid; we want to give you the true watchword of the struggle.’ We merely show the world why it actually struggles; and consciousness is something that the world must acquire even if it does not want to.” This is a straightforward formulation of the idea of immanent critique. It did not, however, suffice on its own. As they read on, they saw that Marx went on to apply this critical theory in his “Introduction to a Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right. ” “Man, he begins there, “is not an abstract essence existing outside the world. Man is the world of men, state, society.” The task of the immanent critique is “to make these reified relations dance by singing to them their own melody.” As his analysis becomes more concrete, step by immanent step, the “man” from whom Marx began becomes the “proletariat.” In this incarnation, the “world of men” is an object that is produced by a certain type of self-reflective society; yet it remains always a subject capable of praxis and understanding—of making a revolution!

The problem for the New Left was that this proletariat conceptualized by Marx no longer existed. That seemed to leave two options for a revolutionary theory of immanent critique. The first would pursue the project on the terrain of culture that had been staked out by Adorno, and by the increasingly popular Walter Benjamin. Elements of this option have been described recently by Philipp Felsch’s study, Der lange Sommer der Theorie. Geschichte einer Revolte, 1960-1990, which reconstructs the integration of French deconstruction theory into Germany by the efforts of the publishers of the Merve Verlag.[32] Most of the story that Felsch recounts takes place outside of the framework of the present account. However one factoid that he cites at the outset points toward the second option for a radical left.

At the time of his death while in prison, the founder of the terrorist Red Brigades, Andreas Baader, had become an voracious consumer of the works of Marx, Marcuse, and Reich; nearly 400 volumes were found in his cell. Baader represented an extreme version of the other option for the New Left: an actionism, which claimed to be a praxis that did in its way what Marx had advocated for critical theory. Although the activists have thought they could “make the reified relations dance by singing before them their own melody,” the song that they sung opposed their ownviolence to that of an unjust society. It is true 1968 was a year that had seen the French May events, followed by the police violence at the democratic party convention in Chicago, the pursuit of the war in Vietnam and the crushing of Prague spring by Soviet and allied tanks. The “praxis faction” argued that by provoking state-violence their actions would force the ruling class to reveal the iron fist within its velvet glove. This superficial and antipoliticaloption was rightly denounced as “left wing fascism” by the heir to the Frankfurt School, Jürgen Habermas, assembly of 2000 activists on June 2, 1968. Although he later admitted that this was no doubt a bad choice of words, Habermas point was telling.[33]

With the turn to violence what I called at the outset the New Left’s age of innocence came to an end. The search for an “unknown dimension” continued, although Marx was no longer considered to be its origin. In France in the mid-1970s, as if to atone for past orthodoxies, anti-totalitarianism became an inspiration for a number of former New Left intellectuals. In Eastern Europe, anti-totalitarianism became a practical reality; in 1989 the Berlin Wall came down, and in 1991 the Soviet Union disappeared. As was the case for many participants in Telosduring the 1980s, it seemed to many that a newNew Left could take shape within the spaces of a “civil society” that conserved its autonomy. This conceptual hope expressed a familiar concept for the heirs to the earlier New Left who had read the young Marx. Those who adopted it unfortunately did not pay sufficient attention to the origin of the concept with Hegel, who saw civil society as only a particular mediation between the immediacy of family life, and the universality of the political state. An autonomous civil society cannot stand alone. The political renewal of the mediations that Hegel called the family and the state stands today as the “unknown dimension” that could animate a newNew Left. Marx may well continue to offer his help in the search for what he had called at the beginning of his own quest to found a “new Athens on another element.”

Notes

[1]C.f. the collection of essays that Karl E. Klare and I co-edited, The Unknown Dimension. European Marxism since Lenin(New York: Basic Books, 1972). The subtitle makes clear our political intention.

[2]My translation from the note in the “Vorarbeiten” titled by its editors “Nodal Points in the Development of Philosophy” as published in Karl Marx. Frühe Schriften, H-J Lieber and Peter Furth, editors (Stuttgart: Cotta Verlag, 1962), p. 104.

[3]John Rawls’ Theory of Justice,published only in 1971, plays no role in the story I am telling. As for the British, the existence of a still vibrant trade union tradition helps to explain the persistence of a more-or-less orthodox Marxist orientation among leftists.

[4]The climate changed rapidly; commercial publishers saw a market. Not known for critical perspicacity, one of the commercial editors, Doubleday, pushed their luck with the publication of a 450 page compilation of The Essential Stalin: Major Theoretical Writings, 1905-1952, edited by Stanford University professor, Bruce Franklin. C.f. the ironic critical review by Paul Breines in TelosNo. 15 (Spring 1973).

[5]C.f., “French New Working Class Theory” (Vol. III, No. 2, May 1969) and “Genetic Economics vs. Dialectical Materialism” (Vol. III, No. 4, August 1969). My edition of the Selected Political Writings of Rosa Luxemburg(New York: Monthly Review Press, 1971) was designated “A RadicalAmerica Book.”

[6]Robert Zwarg has recently published a lucid, richly detailed and critically argued study of Die Kritische Theorie in Amerika. Das Nachleben einer Tradition(Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2017). Zwarg uses the development of Telosand New German Critiqueto trace the afterlife of the Frankfurt tradition of critical theory. In the course of his presentation, he also offers a generous account of Radical Americaas well.

[7]The issue also included my essay “On Marx’s Critical Theory” which used the recently discovered manuscript of Marx’s Resultate des unmittelbaren Produktionsprozessesto demonstrate a continuity between the social analysis of the young Marx and the work of the mature political economist. As Rosa Luxemburg (whose work I was editing at the time) intuited, capitalism and its contradictions can only be understood as a system of social reproduction.

[8]I had an early experience of the weight of Marxist orthodoxy at a conference on Rosa Luxemburg in Italy in 1973. My presentation asked how Rosa Luxemburg could beat once the most innovative of Marxist activists and yet the most dogmatic defender of Marx’s texts (for example, against Bernstein’s revisionism). As it happens, the following day saw the coup d’état in Chile against the Socialist government of Salvador Allende. I instantly became persona non grata! A revised version of that paper was published in Telos, issue 18, “Rethinking Rosa Luxemburg” (and reprinted in The Marxian Legacy). Another example of this kind of pressure is seen in Trent Schroyer’s article in issue 12 of Telos, “The Dialectical Foundations of Critical Theory,” the author feels compelled to begin his discussion of Habermas with an apology: “Despite the vilification of the left, and to the dismay of the academy, Jürgen Habermas remains a Marxist.”

[9]My introductory essays situated historically the two co-founders of the journal Socialisme ou Barbariein the context of French leftist politics and political theory. They became the basis of the chapters on Lefort and Castoriadis published in The Marxian Legacy.

[10]The last article that I published, “Enlightened Despotism and Democracy” (in issue 33, Fall 1977) built from an historical reconstruction to pose a question that led me to turn from the model of the French revolution to reconsider the history of the American revolution. The article touched as well on themes that became basic to the critique of totalitarianism.

[11]A far-reaching synthesis that I found convincing was published in 1992 by two editors whose contribution to Teloshad been significant was important was published Jean L. Cohen and Andrew Arato,in Civil Society and Political Theory(Cambridge: MIT Press, 1992). Both Cohen and Arato, as well as Heller and Feher , finally left Telosby the early 1990s, when they were unable to overcome the influence of the Schmittian grand theorists

[12]C.f., “A Politics in Search of the Political,” Theory and Society,1, 1974, pp. 271-306; “The Return of the Political,” Thesis Eleven, Nr. 8, 1984, pp. 77-91; and “A Political Theory for Marxism,” New Political Science, Nr. 13, Winter 1984, pp. 5-26.

[13]C.f his declaration of refusal, reprinted in https://www.nybooks.com/articles/1964/12/17/sartre-on-the-nobel-prize/

[14]I later used my pseudonym when I published an article on Czech student dissidents that relied on information that could have harmed friends there. C.f., “Czech-Mating Stalinism” in Commonweal, May 17, 1968. I refer below to my debt to the dissidents whom I knew in the 1960s. It should be noted that although both Communists and Trotskyists claimed the legacy of Marx, they were far more justified when they presented themselves as heirs to Lenin!

[15]I knew already from reading one of the few books on Marx that was widely available in the U.S., C. Wright Mills The Marxists (New York: Penguin Books, 1962), that the crucial problem for a contemporary Marxist would be to define what the “working class” could mean in contemporary societies.

[16]All three of these books were published by the Éditions du Seuil. I discuss the theories of Mallet and Gorz in The Unknown Dimension, op. cit. I return to his later work in the ‘Afterword’ to the second edition of The Marxian Legacyand reconsider his philosophical path in chapter 7 of Between Politics and Antipolitics.

[17]Gorz’s idea of a “new left” differed from my own vague understanding; his was strongly influenced by the Italian trade union theorists around the CGIL. After we had become friends, he once told me that he was the editor who had refused to publish my essay on the American New Left in Les Temps Modernes, even though it had been accepted in an official letter by his colleague, Claude Lanzmann.

[18]The former, I came to learn, identified with Maoism, the latter with one of the two Trotskyist factions. At the time, neither my knowledge of French nor my understanding of Marxist scholastics were sufficient to grasp the distinction. I did write, in early June, an account of the May events on the basis of my experience. A copy was sent by courier (the post office was closed) to the journal Viet Report. I do not know whether it arrived. Meanwhile, a friend in London who borrowed by carbon copy never returned it!

[19]I was part of the overflow crowd at Althusser’s lecture, “Lénine et la philosophie,” at the Société Française de Philosophie on February 24, 1968. Althusser, who remained a party member, could appeal to the science of structures to criticize forms of “ideology” that didn’t fit the prevailing party views.

[20](Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1972).

[21]Published in Towards a New Marxism(St. Louis: Telos Press, 1973). This publication was no doubt a sign of Telos’self-confidence rather than of the result of rejection by commercial publishers. I would similarly publish my first work with small leftist publications “outside the mainstream.” Another reason for these publications was the intense desire to communicate, immediately, with others caught up in the same ‘movement’. C.f., the chapter on Sartre in The Marxian Legacy.

[22]The volume was published under the pseudonym of Epistémon (Paris: Fayard, 1968). Its author was Didier Anzieu, a psychoanalyst and professor of psychology at Nanterre; and his title is of course a word play on John Reed’s well-known account of the Russian Revolution as “Seven Days that Shook the World.”

[23]C.f., Esprit, mars 1968, pp. 506-508.

[24]The German edition was first published in 1936. The English translation by David Carr appeared in 1970. Telos published some fragments of Husserl’s text without authorization (in Number 4, Fall 1969). Affirming its political principles, the editorial page insisted that “Since ideas should neither be sold nor bought, none of the included material is copyrighted and can be used for any purpose whatsoever by anyone. It did the same with chapters from Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s as yet untranslated Adventures of the Dialecticin Numbers 6 and 7. The English translation by Joseph Bien appeared only in 1973.

[25]C.f., volume 4, Fall 1969.

[26]I had been there, and agreed. It had been Ricoeur’s support that brought me to Paris, in part on the basis of an exchange of letters in which I tried to show how I thought phenomenology could provide the basis for rethinking new left and antiwar politics. See Ricoeur’s letters of May 15, 1965 and November 5, 1965, and my letter of February 6, 1966, in DH Archive at Stony Brook University.

I should add, however, that David Carr, the English translator of Husserl’s Krisis, who was also at the conference, pointed out to me that his impression was that there was perhaps too much, but too vague a discussion of the life-world. He himself presented a paper on that theme. C.f. his “Diskussionsbeitrag,” to the publication of the papers presented: Vérité et vérification/Wahrheit und Verifikation (Actes du 4ème Collques internationale de Phénoménologie), ed. H. L. Van Breda (The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1974), pp. 95-96.

[27]I leave aside the very different interpretation of the life-world and lived-experience by Heidegger. It did not play a significant role among readers of Telos, although most did read the (difficult if not unreadable) translation into English and some were fascinated by its still influential French variant.

[28]Students for a Democratic Society had been the youth organization of the Social Democratic League for Industrial Democracy. It declared its autonomy from its parent in 1960.

[29]In fact, the generally available and inexpensive East German edition (the Marx Engels Werke, familiarly called “die blauen Bänder) did not include many of the early philosophical work of the young Marx. These could be found in the more expensive edition of the Frühe Schriftenpublished by the Cotta Verlag only in 1962.

[30]Perhaps in the Enlightenment tradition, when Amsterdam was a center of pirate editions, the last-named book had a publisher (Amsterdam: Verlag de Munter, 1967), the others were usually done by anonymous collectives and were undated There were other pirate editions, for example of Karl Korsch and of Wilhelm Reich’s 1934 journal calledSex-Pol(as well as a pocket-sized, illustrated version of Der sexuelle Kampf der Jugend). One found also editions of authors who had abandoned their former political theories, such as Karl August Wittfogel, Franz Borkenau, and Richard Löwenthal (under the pseudonym Paul Sering). Another large volume, retyped by anonymous collaborators (like the Samizat publications that helped bring down the Soviet Union), previously published texts from academic journals under the title Kritik und Interpretation der Kritischen Theorie: über Adorno, Horkheimer, Marcuse, Benjamin, Habermas.

[31]All three essays appeared in volume 6 of the Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung(1937), which was copyrighted in Paris by the Librairie Félix Alcan in 1938.

[32]München: Verlag C.H. Beck, 2015).

[33]C.f., the reconstruction of Habermas’ philosophical development in The Marxian Legacy. I keep this theoretical development separate from his political writings in chapter 8, which are the subject of chapter 8, “Citizen Habermas,” republished in Between Politics and Antipolitics. Thinking about Politics after 9/11 (New York & London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016). At the time, international connections were strong, as reflected in for example Alfred Schmidt’s contribution to The Unknown Dimension. I knew many of f the SDS leaders from Frankfurt criticized by Habermas, including the charismatic Hans-Jürgen Krahl, whose necrology, as noted above, was published in Telos. Others, such as Rainer Zoll, who had left the university to work for the IG Metal (but returned to a post in Bremen somewhat later), helped put the excesses in perspective.