The Road Not (Yet) Taken I: Exposing the Roots of the Contemporary Reaction

But, if one has dreamed an empire, the empire of man, and if one dares to reflect at what a snail’s pace men are advancing toward the realization of this dream, it is quite possible” that the “activities of man pale to insignificance.”

–Henry Miller

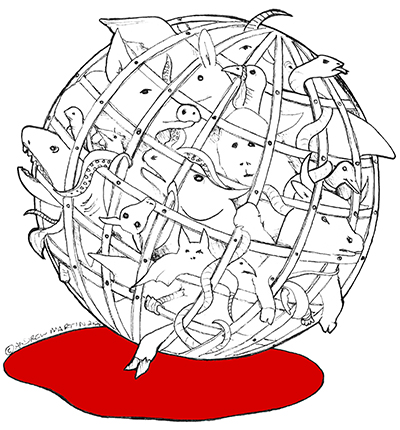

Lemmings race ahead, focused on following the one in front of them. Do they know there is a cliff ahead? Do they know what they do not know? If they did, would they step back, reassess, perhaps turn around?

With the egregious elite assault on the institutions and practices of American society and the escalating crisis in the streets producing ubiquitous (though understandable) refrains of political and cultural despair, our sense of history narrows.

What lies submerged in these exigencies, we forget at our peril, is the long-standing American promise that its unprecedented opportunities – if justly managed – would produce a distinctively modern collective featuring empowered and more fully realized individuals and greater equity for all members.succumbing to the vilification of alternatives by these forces of reaction, in effect reading them out of the foreshortened narrative of their ascendancy, we find ourselves unable to identify and coalesce a broader dynamic of foundational structural and conceptual change.

In order to reanimate the transformative dynamic emerging less than a half-century ago, it is crucial to explain how these initiatives and indeed the very mention of basic changes were derailed in the intervening years. This investigation in turn raises complex and troubling problems of causation, for the success of the Reaction was by no means the simple result of its own – however strenuous – efforts. To the contrary, its increasing domination of the political arena and popular discourse since 1980 resulted only in part from the organized obstructionism and ideological nihilism of reactionary forces seeking control. To a greater extent, this was achieved by its reading of the vacuum of cultural legitimacy, institutional cohesion, and political coherence throughout society. Its proponents recognized the devastating impact of the fundamental challenge to liberal ideology and assumptions in the 1960s and the collapse of its aura of inviolable consensus. Seizing upon the increasing resistance to the great scope of changes being proposed from large sectors of the mainstream body politic, including among many nominally liberal constituencies and one-time supporters of restructuring, the Reaction found it quite easy – though it moved with some stealth and much misdirection – to storm the redoubts and establish its ascendancy.

I. The Archeology of Reaction

Because these “culture wars” as they came to be called were fought out over the psychological framing of the individual and subjecthood in late industrial and post-industrial life, an analysis of the divergent premises advanced requires a psycho-political and psycho-cultural appraisal of the contesting views. At the same time, even to identify how these underlying assumptions are now shrouded in ahistorical denial, amnesia, and incontrovertibility, the psychosocial strategies and mechanisms employed to divert popular understanding must first be exposed. One of the primary – for obvious reasons as we will see – functions of Reaction is to cover over, thereby erasing, what it is a reaction to, in reaction against, thereby turning itself from a project of repression – if successful – into a new normal. In this way, the transformative impulses are isolated to fester unattended, stymied outside the city walls – drawbridge up, denied, unheard, ultimately triggering for its practitioners doubts as to their very reality. Thus a probing analysis of Reaction during its period of presumptive ascendancy must be ultimately an archeology.

The effort at disinterring movement origins is made decisively more difficult when the leading force of Reaction is an imperial power. When the repression of change occurs, for example, in a family situation, typically against the young, or in a particular political region, the evident solution is to pick up with one’s world-view intact and leave. When many still believed in an oasis identified as America, its many immigrants for one or more of these reasons undertook the arduous trek to relocate and resettle. But where an imperial power has extended its grasp over the available space and lines of communication, fostering the burial of contrary clues and the narratives of its opponents-cum-enemies and turning the accessible ‘reality’ (as the George W. Bush retainer gloated) into the mirror of its claims, the activist (following Che or Snowden) will need to keep one’s bags packed. For the theorist of change, there is resort to the implement in the tool-belt most necessary at the outset – archeology.

A further, perhaps the most debilitating, hurdle is when one-time proponents of change no longer wish to recall what was at stake beyond whispered regrets for past indiscretions. Where the previous confrontation centered on issues of power and institutional governance, such lapses of memory are less likely to impede inquiry. This is illustrated in the classic movie of revolution, The Battle of Algiers: though the Algerian insurgent leaders are all hunted down and killed by the French Occupation, the popular movement soon reemerges as a tidal wave that presses on to national independence. Or when, under similar circumstances, opposition leaders join the oppressive system, the fingerprints of imperial intimidation and bribery leave the pathway to betrayal exposed.

The situation is more delicate when the initiating movement challenges existing psychosocial priorities, the dominant values and meanings disseminated in society which people have internalized as the basis of their identity. In this case, the dreams that once moved proponents of transformation but move them no longer are easily lost. Moreover, given the internal burden even at high tide of undertaking such deep recastings, the inevitable doubts about goals, confusions regarding direction, guilt about the magnitude of the demands, thoughts recurring of retraction, the fires of change can all too easily turn to ash with the mounting gusts of contrary winds. Because such reassessments of large-scale attitudes and priorities are rare, they can be unceremoniously jettisoned as part of the unwieldy baggage impeding the process of maturation. The invitation to return, to reintegrate upon proof of disavowal, will then be snapped up, chapters in one’s autobiography excised, childish romances wisely surmounted by the evolving subject, second-order (though never completely erased) amnesia subtly merged with the first-order sleepwalking of all others, leaving hidden beneath the overlay of fresh soil the dimmest outline of previous tels, protrusions, symptoms, hidden chambers, dismantled launching pads, arrested selves. You can walk on it, no problem, says the landscaper, this land was never inhabited, too much groundwater, beware of dumpsites.

And, finally, if one is able to locate those persevering long enough to remember, those rare guardians of the spirit who have not relented, one will be chastened by their test of endurance against the severe forces of repression and pressures of self-doubt. After many decades of Reaction, they may have shifted default settings from a narrative of progressive human unfolding and collective advance to one of heartbreaking spiritual withdrawal and societal decline. In this way, the Reaction has forced even its most stalwart opponents to concede the initiative to the enemies of change, leaving the high ground, the beacon light of transformation, the inner fires of self-transvaluation, depopulated and abandoned, voiceless fantasies that visit and depart in the night.

How can one respond to this sweeping reaction, both willful and habitual, conscious and unconscious, hostile and regretful, aggressive and inadvertent? How does one penetrate the fantasy of the New Normal as the abiding operation of the everyday, of everything one sees outside the window of one’s soul, to insist that Reaction has turned individuals into marionettes, scripted ventriloquists, who have learned to function without their strings? The archeological method is admittedly a hunt for traction on a vast surface of ice. A contrasting method would begin at the other end, as Rousseau in the Second Discourse, by positing a reimagined and restored vision of the fully human unworn and uneroded by the incessant forces of civilizational abrasion and despoliation. And yet, employing the trope of the presocial individual to in effect construct a reverse archeology merely highlights not recovery but loss: forced to watch the progressive deformation of the human as the ideal prototype is set into the flow of history, the culmination will be an irreversible dystopian present.

To the narratives of decline and dehumanization (which Rousseau fully surmounts in Emile), I propose beginning with the outermost symptoms of present delusion and obfuscation, the cul-de-sac of lemming-like behavior, with the goal of sequentially unearthing and interrogating the artifice of psychosocial reactivity and denial. Utilizing the surgical tools of Nietzschean genealogy, we can systematically retrace the patterns of disguised and rationalized malformations to recover the original impulses as they are first turned against their own development. Channeling the spirit of his archeology of the complex web of Judeo-Christian repression, the resistances – fears, resentments, uncertainties, self-doubts presenting as worldly cynicism, ridicule of opponents’ grandiosity and illusions, scapegoating, a sense of grievance at feeling challenged, rage at having no answers, tragic virtue, a theology of absolute limits – can be exposed. Recovering these patterns at their inception will reveal their source in the panic of being unprepared, that is, unequipped, overmatched, and undone, by novel dreams and wishes that were feared forever out of reach. Behind this giant swell of aggression, then, are those very dreams and wishes lighting the path to genuine psychosocial transformation.

II. The Dig

The most evident sign of the Reaction’s success in redefining the political landscape and cultural trajectory is the fixation in an deluge of books, articles, and blog posts across the entire political spectrum – apart from Trump loyalists –– with what form of post-liberal system is emerging. Are we witnessing a coup, a putsch, or a constitutional take-over? Can the result be more accurately labeled as authoritarian, fascist, or plebiscitary dictatorship? The assumption, however unspoken or unrecognized, is that the Reaction has advanced beyond resistance against previously spurned ends to an independent historical dynamic with ends of its own. As I write this with less than two months to the general election 2020, Trump’s Republican Party has put forth no proposals, no policies, no initiatives, no plan for governance, no responses whatever or even press releases regarding the escalating pandemic, economic collapse, ecological crisis, or exposure of endemic structural racism. The only signs from the campaign are the unending 24/7 barrage of micro and macroaggressions against candidates, organizations, movements, and journalists who insist that something be done. The common element behind this firestorm of negativity is refusal – “thou shalt not” – indicating no change or remediation is acceptable. The marketing brand is a Wall, call it “law and order” or racialized stimatization or ‘socialism’ or armed border, the last barrier protecting Us from Them, all of them approaching everywhere.

This is the quintessence of Reaction, demanding by its fervor and single-mindedness to be accorded an independent legitimacy. Yet to accede to this analysis by decibel level ignores the candor which marks the most recent stage of Reaction. In earlier stages, from Ronald Reagan to Bush II and the Tea Party, the backlash was disguised. Its motives were veiled in ever more deceptive and incongruous ideological positions that tapped into nostalgic myths of an arcadian, white, father-knows-best world that bore no relation to the rightward thrust toward corporate control, elite political dominance, and patriarchal authority. Many Americans, far more than admitted it, were beguiled by the good faith of seemingly innocent Trojan horses which (somehow? inadvertently?) formed impermeable roadblocks to change: a balanced budget, smaller government, less federal activism, states’ rights, free market, judicial restraint and Constitutional originalism, lower taxes, deficit reduction, color-blindness, meritocratic rigor, educational excellence, family values, a right to ‘life’ (until birth).

These presumptive ends have now been plainly revealed – as each in short order has collapsed into its opposite with the right wing institutional takeover – to be merely weapons in the ideological defense of the status quo. For most analysts evaluating the new right takeover, however, this shameless gloating at their nearly transparent deceit has paradoxically confirmed the claim of its independent dynamic. Rather than link this disinformation to the larger pattern of reactivity, which would have required asking about reaction to what, a sweeping claim is abruptly put forth that these motivations should be understood as primary, elemental, first order, nothing beyond the incessant human drive for power and control evident in the way groups make history. Yet, resort to this apparently uncontroversial truism had the chilling effect of utterly ignoring, burying, the 1960s reassessment of the psychopolitics of late modernity.

Claiming the ubiquity of domination marginalizes the psychopolitical transvaluation initiated by the early post-industrial initiative for transformation: that the motives now decoupled from reaction are precisely reactive in their intent, the very drives that form in response to, to fill the gaps from, misshapen psychodynamic development. This bundle of needs for “power over,” the obsession with “domination,” stems according to influential psychoanalyst Erich Fromm as one’s deformed response to an early “atrophy of the generative capacity” to exercise “power to,” that is, the internal “capacity” to “make productive use of his power.” As Fromm explained, where genuine “potency is lacking, a man’s relatedness to the world is perverted into a desire to dominate, to exert power over others as though they were things.”[i]

By reinstating the drive to dominate as a core, perhaps the core, motivation, any traction to assert the derivative character of the Reaction is lost. More significant yet, since this transvaluation was originally intended to challenge the broader claim of Western and American liberalism regarding its incentives and practices, its very view of human nature, the net effect is to insulate the liberal project from fundamental critique. In this critique, the liberal psychology of motivations based on instrumental, that is, utilitarian, hyper-competitive, aggrandizing, acquisitive, and materially rather than humanistically oriented, drives, was by no means primary. To the contrary, this motivational system was narrowly constructed and adapted to advancing the early modern economic ascent.

Whatever the justifications for containing human development in furtherance of production, the emergence of late industrial and post-industrial prosperity and plenitude along with the growing resource constraints meant that these constricted incentives could be significantly relaxed and replaced by catalysts for fuller self-development. The goal was to finally address the diminished sense of self and self-motivation demanded by productive discipline and self-repression, to confront the liberal insistence on developmental arrest, on treating frustrated and unrealized potentialities for personal and collective well being as inevitable. Thus, the retreat to undiscriminating claims of domination ignores why such developmental aspirations could trigger the virulent rage and destructiveness now being unleashed that is tilting the nation to the edge of structural breakdown, moral nihilism, and social regression. Its effect is to support the reactionary claim that nothing changes and even the wish for human advancement is delusional. Values and aspirations in this view are simply the window dressing for the ubiquity of power over, rendering the initiative to support healthier developmental potentialities along with the American Dream itself merely window dressings for national expansion, group contestation, and the inevitability of elite ascendancy.

Because the rise of the Reaction has forced reconsideration not only of the current period but the entire twentieth century American idyll of growing liberal ascendancy, it was to be hoped that the longer-term causes of liberal fragmentation would be examined. But the reactionary – however inadvertent – reading of the present crisis has become the predominant and even default analysis, absent any clue about the deeper forces, regarding the contemporary period as a whole. Before Trump’s election, the reigning national narrative asserted the further consolidation and global ascendancy of the American system reflecting (using the term coined in 1996) the “indispensable nation.”[ii] With the collapse of the Soviet Union and the culmination of American ascendancy, the American century would be proclaimed as the “end of history.”[iii] With Trump’s ascension, however, the insulation of the official American story, the story of “American democracy” that was “never supposed to” lead to this dark place, was with mounting evidence of deeper divisions and systemic instabilities finally breached.[iv] As Trump’s far-flung apparachiki pursued a wholesale dismantling of every aspect of the modern liberal state, domestically and internationally, together with all checks and balances and organs of oversight, in order to facilitate a strong-man rule, it was increasingly apparent that an “illiberal democracy” was emerging.[v] The hollowing out of the institutional and electoral processes could no longer be localized to recent or discrete structural malformations.

From an October 2017 conference at Yale entitled “How Do Democracies Fall Apart (And Could It Happen Here?)” to a spate of books – distinguishing between doomsday renderings and brinksmanship warnings – forecasting the collapse of American popular government, the era of self-righteous complacency had come to an ignominious end. But how was this unraveling in the era of presumed national triumph and vindication to be explained? As mainstream analysts conceded that the evident systemic infirmities could not have simply appeared in 2016, a longer-term replacement for the conventional narrative, now clearly the product of at best wishful thinking, at worst cynical ideology, capable of explaining the gradual descent into crisis and delusion had to be framed. Yet how, given that few, including the analysts themselves, had ever entertained such a possibility, could this narrative be shaped to rebut charges of myopia and even collusion? Peering gingerly beneath the evident trends, the solution chosen wove together wishful thinking and cynicism in a narrative of exculpability: a trusting liberal mainstream had been ambushed by the stealth drive to power always motivating the most illiberal forces in the society.

In this way, the entire contemporary era would be reframed (indicating that Trumpism is not the only conspiracy theory) as Americans settling back to enjoy the well-earned fruits of national apotheosis sandbagged by resentful outliers. At work for decades, we were told, had been Kurt Andersen’s “evil geniuses,” Corey Robin’s “The Reactionary Mind,” Michelle Goldberg’s “corrupt authoritarian populists,”[vi] Ruth Ben-Ghiat’s “various anti-democratic forces,”[vii] and Rick Perlstein’s reactionary movement coalescing plutocratic manipulators, populist “con artists and tribunes of white rage,” legions of “far-right vigilantism and outright fascism,”[viii] and teeming fellow travelers priming the broader electorate for Trump and the structural consolidation of right-wing control. Even long-time right-wing political operative Stuart Stevens in his book It was All a Lie: How the Republican Party Became Donald Trump explains how the core principles Republicans had always pretended to represent were summarily dismissed once the goal of unfettered power became available, allowing them to reveal their ‘true selves.’

The deeper force being beckoned as the culprit is of course the ubiquity of ‘power over,’ fully evident in Perlstein’s linkage of recent American history with Europe in the 1930s and South America in the 1970s. The liberal historians – including in his assessment Perlstein himself – charged with overseeing the national narrative had taken their eyes off the ball, seduced as most Americans by the prospect of concord in our time. Yet Perlstein’s greatest contempt is for the New Left and counterculture entrenched in their celebratory bubble of cultural release, convincing themselves on drug-induced highs that society as a whole was following just behind. Inflating a minor trend more tied to expanding consumption that serious social change, these cohorts simply discounted any attention to the realities of power, not only their own trivial impact but the surging reaction to their normlessness and licentiousness. And if pride of place had not already been accorded to ‘power over,’ Isabel Wilkerson’s recent book Caste enshrines savage status disparities at the base of civilization, rendering ideals of freedom and equality even at their most genuine the tragic orphans of history.[ix]

III. The First Usable Artifacts

Clearing away the layer covering the site with the effort to define historical processes by conditional and provisional constellations of dominance, replications of the crude calculus of tyrants and hegemons (what could Jesus with eleven disciples have been thinking), excavation now offers greater visibility of the actual forces at work. Even as the radical right takeover presumably illustrates the essentialism of ‘power over,’ this quest for control was mobilized among diverse constituencies from the start in response to troubling trends connected with post-industrialism. In his 2004 book What’s the Matter with Kansas?, Thomas Frank identified “cultural anger” as the primary motivation mobilizing the popular backlash against cultural liberalization.[x] Easily stoked and marshaled by the brokers of plutocratic control, this rage as Frank notes intensified even as it was being exploited to produce growing economic stress for most supporters. From the perspective of the cultural right, those committed to evangelical and Christian populism, patriarchy, local status elites, white supremacy, and American hegemony, this was a small price to pay for the fervent defense of inscribed American values in the face of assault by emerging cadres of permissiveness and amorality.

While quickly labeled as a reaction to religious and cultural changes, the movement was to partisans a defense of existing patterns and an assertion of bedrock principles. And in purely formal terms, assuming a world where nothing is ever allowed to change, this is a plausible argument.[xi] And yet, though possessors of one-time certitudes felt unjustly pressured by the need under changing circumstance to advance a more compelling explanation than having gotten there first, the assumption of a static world is in the most literal sense reactionary. At the same time, the cause of Reaction to its credit was not at base a question of first filing (who came first or deserved to thus pales) but a deeper claim regarding human psychology and selfhood. The right wing project as announced and propounded by its early advocates was grounded in the classic Protestant-liberal demand of obedience to interdictory authority which it found under intense and nearly fatal pressure from the sixties culture encouraging the release, gratification, and expression of impulses.[xii]

Maintaining those authorities that enforce norms of disciplinary rectitude through the repression and sublimation of primary impulses – religious leaders, parents, fathers, husbands, teachers, racialized hierarchies, Americans, moneyed elites – meant defending their institutional and persuasive power over the public. For some critics, this reinscription of interdictory elites was an effort to undermine the rising expectations of less empowered groups in order to protect elite privilege regarding discretionary consumption and expression. While certainly an aspect of the campaign, to render this account of class war more dispositive requires showing that its class opponents mobilized to contest the demand for greater controls. In fact, despite both mainstream demonization and praise now accorded for the politically astute offensive waged by the plutocrats, not only the people from Kansas but liberals and progressives surrendered before a shot was fired. From Ronald Reagan’s duplicitous rollout of a white picket-fence America of small business revival and patriarchal family values, authority over the young, and a godly nation of moral obedience and certainty, people from every demographic and attitude set joined in the chorus chanting about the nation’s social and psychological recovery.

Demonstrably bereft of evidence, this ideology of return was swallowed in whole cloth by the Democratic Party, providing refuge for the Clinton and Obama administrations as they abandoned their core values of broader benefits and higher standards of living as well as their constituencies that had hoped for relief.[xiii] They ditched any mention of cultural or lifestyle transitions and popular demands for power and equity sweeping the nation as well as programs that challenged corporate leadership, fearing the charge of resuming support for a less repressive society with its psychosocial dislocations and identity confusions. Joining in the conventional wisdom, they too hoped that, once the picket-fences were in place, no one would thereafter look for what lay on the other side.

The cards of constraint that were played overrun the site, but people looked and they saw unmistakable signs of plenty. Barriers more compelling than a return to village morality would have to be put in place to confront the forces of post-industrial change. The Reaction would be forced to come up with an ace in the hole, which would with some key shifts in emphasis become the axiom in the sand guiding its ascendance.

IV. The Big(gest) Lie

What could actually be recovered in the nostalgic revival of self-repression (as opposed to self-mastery) that was not hopelessly tattered? That could provide systemic restraint in the face of not only emerging dreams of liberation but a society consistently propelled beyond norms of moral and psychological moderation by merchants and models of excess? The framework for the eventual underpinning of the Reaction, the foundation or floor plan if you will lying beneath the sediment upon which their artifacts rested, had actually been identified and set forth in its early, more theoretical phase. As soon as the transformative initiatives, and particularly the new view of selfhood emerging from it, were recognized in the late sixties as a total repudiation of the liberal paradigm, it was clear that its fundamental compromises and curtailments of human possibility could no longer be claimed to be materially inevitable. The case would now have to be made that they were necessary.

If the transformative culture’s operative premises – and not simply its manifestations and symptoms – were to be thoroughly gutted, the claim had to be advanced that abundance was (regardless of whatever material advantages it brought) psychologically unsupportable, a site clearing demolition of the stanchions upon which the liberal capitalist self and world rested and rose. Underlying the waves of strategic deployment designed to generate popular revulsion to cultural transformation – from early conservative psychocultural doomsaying and the evangelical preaching of divine judgment to market sacrality, bullying nationalism, and terror of insurgency at home and abroad – circulated a big lie: the claim, first announced by Reagan with stern avuncular mendacity, that America was at the time of his election campaign in 1980 in the throes of a ‘productivity crisis.’

All the stops were pulled out, right wing think tanks with their cooked statistical reports, conservative policy makers, corporate leaders, political Cassandras, cautious backpeddling liberals and progressives, to warn of an eroding work ethic and entrepreneurial spirit, populist threats to profitability, merit, innovation, and reward, and at the unholy center the specter of prolonged economic decline and scarcity. Its effectiveness in deflating all aspirations for change, and in providing talking points for the great multitudes needing an argument for retreat, was soon demonstrated in energizing the many fronts of Reaction. All of a sudden abundance had become redefined as scarcity, although only an imperial culture could enforce the emperor’s outlandish suit of new clothes. For the great problem with this assessment was that it was not – not even a little bit – true. But after pulling off to near universal support this big(gest) lie of all, it is easy to see how the other big lies would fall into place.

On the most evident level, the apprehension being stoked was that the widely cultivated fantasy of unlimited abundance after World War II was under threat from counterculture and reformist demands for a shift away from consumption to other personal and collective forms of well being. The claim that the only alternative to limitless consumption was recognizing some scarcities was of course true, but the assertion that limitlessness was desirable and sustainable was not the work of the opposition but the marketing mumbo-jumbo designed to maintain the wheels of production and consumption regardless of necessity. At the same time, it served to deflect reexamination of this false polarity crying for reexamination at precisely the time of rising access to expanding post-industrial production to challenge the materialist mania and to ask what was genuinely desired and needed.

Moreover, though unwelcome news, liberal thinkers had for more than a half-century foreseen and postulated this very shift. The awkward concern facing an insistence on ineradicable scarcity was the declaration by dominant mainstream thinkers beginning before the turn of the century that the material problem was being solved. With the takeoff of the industrial economy, producing the wealthiest society in human history, many important thinkers including John Dewey and Thorstein Veblen accentuated the dramatic new prospect: the issue was no longer whether vast wealth could be created, and created more efficiently, but how it would be used. Lester Ward, the founder of American sociology, framed the seismic shift from production with its imperatives of functional utility to distribution and the satisfaction of societal and personal well being: “desires,” Ward wrote at the end of the nineteenth century, are now the “dynamic agent” in society, the “universal force” behind all “social forces,” reorienting as the larger societal goal to “produce and distribute the objects of desire.”[xiv] This turn to a consumption-based system grounded in a gratification rationale signaled the very reframing of liberal society from a participatory, institution-building republic grounded in restraint to a dispensary of consumption with the continual opportunity for expanded gratification.

With rapidly expanding production, a situation of surplus was created as early as the 1920s, where the output from excess plant capacity and technological advances as well as of consumer, including agricultural, goods, could not be absorbed within the existing system of distribution. In a profit-driven economy, the necessary restrictions on wages limiting consumption created cascading overproduction and the collapse of prices and profits, leading in turn to the Great Depression.[xv] Scarcity thus had to be restored artificially through the curtailment of production rather than by restructuring distribution, a retreat from affluence that remained intractable until war preparations reestablished the priority of maximizing production. Even given the immense waste of resources and output from a prolonged world war, the technologically innovative, full production war economy created after World War II what was broadly recognized as the first discretionary economic system and the harbinger of the emerging post-industrial age.

This world-transforming stage was famously identified by noted economist John Kenneth Galbraith in 1958 as the “affluent society.” This constituted an alteration of such magnitude that the “ordinary individual” now had access to the wide range of “amenities” previously unavailable even to the rich, and if the focus remained consumption individuals would “need[] an adman to tell them what they want[].”[xvi] Erich Fromm as early as 1947 in Man for Himself spoke of the unprecedented condition of a “material world” which “surpasses” even the “dreams and visions” of the past, a world in which the age-old “problem of production” has “in principle” been “solved.”[xvii] In these books as well as David Riesman’s 1957 essay “Abundance for What?” and a collection of essays under that title, Robert Theobald’s The Challenge of Abundance (1961) and many others, Riesman’s provocative question “abundance for what” became the overriding question.

For Riesman, the urgent task was to develop “collective aspirations” and individual “aims” and “motives appropriate to our new forms of peril and opportunity” in the “age of abundance.” This was particularly pressing since society had provided little “re-education” for those “released from underprivilege by mass production and mass leisure” as well from as their “traditional culture.”[xviii] Galbraith warned that those “economic attitudes” formed in the “poverty, inequality, and economic peril of the past,” however “obsolete and contrived” in the present, continue to hold us in “captivity.” Reconfiguring “new tasks and opportunities”[xix] would involve confronting major psychological dislocations. To overcome what Theobald called the “old patterns of selfishness,” the inbred but now dangerous and dysfunctional pursuit of domination originating in times of survival rather than collaboration, was a major concern.[xx] Fromm identified the unprecedented issue to be faced: without the psychic anchor of economic activity and incentives, how do we comprehend “what man is, how he ought to live, and how [his] tremendous energies” can be “released and used productively.”[xxi]

V. The Flight into Scarcity

Given the exponential advance generated by post-industrial automation and rationalization in which the “level of productivity for mass-produced goods is almost independent of the input of human energy,”[xxii] in which a self-managing cornucopia previously confined to mythology was resulting in the “piling up of consumer goods,” self-identified consumption communities, discretionary and conspicuous options galore, how was the retreat from abundance to a condition identified as scarcity effected? Once we exhume the original arguments and claims of the Reaction, the paramount role accorded to scarcity becomes self-evident. On one level, abundance rendered the operation of the capitalist economy unworkable and counterproductive. Stuart Chase uses the example of air: because the earth’s atmosphere is (for the time being) abundant and freely available, it has – though precious – no market worth if offered for sale. But were it under private ownership, its price would be unlimited, though “every man, woman and child in the country would be poorer.”[xxiii]

This argument for maintaining market viability through limiting output, however, would have no attraction for those who now get their air without cost. Scarcity, then, is not a universal principle, but a weapon to be employed selectively. Thus, the task of economic and political elites, reinforced by armies of marketers and advertisers, is to insist that corporate capitalism is the goose that must remain unimpeded in order to lay its golden eggs. But this only pertains if individuals can be convinced that forthcoming innovations (including canisters of clean air) are indispensible and can be obtained in no other way. To bolster this perception, the corporate system must maintain the very artificial scarcity it claims to overcome. Its pipeline of new and improved products and indispensible, cutting-edge services inflicts ever more attenuated distractions to defer the experiences of surfeit and consumption fatigue. Despite declining income and discretionary options in the increasingly skewed economy, the fantasy of continued excess must be sustained to impose the treadmill of hyper-consumption. The arenas of surfeit must in turn be shifted to the virtual sphere with its ceaseless pandering to and marketing of boundlessness. In this way a coordinated strategy is implemented to mandate ever increasing – though ever less useful – and less remunerated levels of work in order to retain access to the fantasy.

While most Americans have some sense of this shell game, they have despite the sacrifices involved resisted serious efforts to dismantle or even question the artificial reimposition of scarcity. They remain unable to address the acute psychological dislocations generated by the post-war reduction of economic pressures and their mad race to discretionary paradise. In a society suffused with economic peril, a shifting and never secure sense of place or status, and weak interpersonal interconnections, individuals have been highly dependent on the psychological security, grounding, identity, connection, and sense of purpose provided by participation in the economic system. This institutional setting alone provided structures of responsibility, institutional functionality, rewards, roles, relationships, and goals. Even its “metronome-like…routine”[xxiv] connected individuals on a daily basis with the larger project shaped by the Protestant work ethic and the narrative of national development, and allowed them to table or forestall the deeper questions of personal meaning, social values, and individual agency that liberation from economic necessity would generate.

In flight from this impact of the relaxation of economic compulsions and obsessions, Americans had inadvertently given lie to their vaunted national ideals with what Erich Fromm presciently called their ‘fear of freedom,’ the socially propagated inability to shape lives independent of external demands and structures. Having allowed themselves to experiment with goals that could not be delivered by conformist liberalism and the capitalist consumer economy, alternative forms of meaning and self-expression, vocation and engagement, new kinds of collaborative relationships, families, and communities, innovative forms of education and non-school learning, reductions of hierarchy, official designations of merit, and wage differentials, in other words, the possibility of lives less repressed and more actualized, Americans lost themselves in the tangle of unprecedented possibilities. Too disoriented to navigate the dramatic new opportunities opened by the world’s first post-industrial system, Americans of every stripe retreated rapidly to the fortified port of endemic scarcity, intent upon banishing the anxiety of liberation.

While this revalidation of scarcity was later effectively moved to other less revealing framings, an archeological perspective reveals how conservative cultural critics in the first wave of attacks on shifting priorities grasped the deep anxieties involved and contentiously insisted that the fate of civilization rested on maintaining scarcity as a psychosocial imperative. Among cultural conservatives mounting this campaign, including many previous partisans of social change, were Christopher Lasch, Philip Rieff, Richard Sennett, Nathan Glazer, Allan Bloom, Daniel Bell, Norman Podhoretz, Irving Kristol, Midge Dechter, Joseph Epstein, Saul Bellow, Gertrude Himmelfarb, and Robert Boyers.

One of the most influential partisans was Daniel Bell, who had early on challenged the counterculture ethos of protean libidinal “boundlessness” unleashed in the 1960s that enticed large sectors of society “straight by day” to become “swingers by night.”[xxv] Bell saw more acutely than most of the liberal center that the industrial and especially post-industrial dynamic of liberal capitalism had eroded the pressures enforcing psychosocial containment. This relentless dynamic had unleashed expanding expectations at all levels in the economy and proliferating once-marginalized groups with demands in the political arena, ultimately allowing expanding claims for opportunity, equity, and fulfillment to be released from the confinements imposed by the traditional ethos of limits. Energized by increasing abundance, the “cultural drive of modernity” and the adversarial culture of the “unrestrained self” had eroded beyond recognition the bulwarks of functional hierarchy and bureaucracy, self-discipline and delayed gratification, deference to political representatives and political elites. This view, adopted by neoconservatives like Allan Bloom, charged that this incendiary match of instinctual release and libidinal indulgence in “self-exploration and self-gratification,” imagination and autonomy, was animating rebellion against all systems of societal order.[xxvi]

Bell quickly grasped the vital leverage to be gained by retaining a scarcity orientation. Caricaturing as utopian, absolutely unconstrained, and irrational the proposed shift from a production-based society, the delusional opposition goal in his view was to “abolish[] all competitiveness and strife,” to promote the fantasy of such a “plethora of goods” that one “would no longer need to delay his gratifications” but rather “throw prudence to the winds, indulge [one’s] prodigal appetites, and live spontaneously and joyously with one another” in a limit-free condition of “polymorphous sexuality” and a “psychedelic” abandonment to “pleasure.” As an extravagant dreamscape intended to discredit the quest for new priorities, it ironically gained traction by mirroring the very liberal capitalist marketing promise of untrammeled surfeit invoked to mobilize continuing economic sacrifice and deferral of change. This liberal ploy had once been promoted with confidence, indeed certainty, that sufficient levels of material well being would remain forever out of reach. But now that a “post-scarcity stage of full abundance” had to be acknowledged even by its opponents, Bell suddenly realized that the premise of abundance offered not a “desirable social” framing but rather a vastly disruptive view of post-industrial liberal order.[xxvii]

In a section of The Coming of Post-Industrial Society (1973) posed as a question “The End of Scarcity?,” Bell argued based on the absurd and excessive distortion he had drawn – advocated by no one – that post-liberal ideals of a humanized society were forever out of reach. Proponents of change just as everyone else would have to concede that scarcity was endemic, that limits rather than possibilities would always predominate. As a result, the continuing instrumental channeling of desire rather than unfolding of new potentialities would be required. As for the scarcities still lingering, aside from offering politically trivial and self-evident limits on time and information access, Bell focused on the one core privation that he believed we were incapable of moderating: the “relative deprivation” experienced from “disparities of income and status” in comparison with more outwardly successful members of one’s “reference group” as well as with others possessing higher levels of power, influence, and reward.[xxviii]

The argument was on one level ingenious: individuals wracked by the sting of competitive disadvantage would remain “enslaved” to the obsession with catching up in the liberal competition for acquisition and display.[xxix] On a more insidious level, as Bell even intuited, this universal assumption of a flagrant pursuit of limitlessness was in another guise the liberal promise that limitations on gratification merely existed to be exceeded. Despite the pervasive questioning of appetitive infinitude, Bell in effect admitted that the indispensible engine driving liberal enterprise was not material but the unfulfillable compulsion toward self-aggrandizement. Liberalism had come face to face in Philip Rieff’s terms with its own demon: the haunting, unacknowledged specter released by consumer capitalism was its fantasy, at once predatorily exploited and grimly feared, of the “endlessly developing Self, mocking, by its consumption of them, all constraints.”[xxx]

Given the sudden realization that it had prepared the way for its own dissolution, the revalidation of restraint, Bell concluded, if not necessarily limiting economic production but certainly non-marketized gratifications, would after the horse had left the barn require resort to a “transcendent ethic” that would “sanctify” self-repression.[xxxi] Rieff pursued the same course, advocating “a return” to “established…authority” with its primary “interdictory” function of enforcing a “science of limits” as always “complete with [its] repressions.”[xxxii] For Rieff, for Sennett in his book Authority (1980), for Adam Seligman, as well as for the rising legions of evangelical interdiction, “establishing the necessary connection of authority to ideas of selfhood” through “community and the sacred,” with its convictions about “shared moral commitments,” can alone generate priorities unshakably constrained by “boundaries” and “commitments.”[xxxiii]

The problem with this strategy for the broad defense of institutional barriers, however, was that from the Reagan era onward those very elites promoting the return to the previous system of controls were abandoning themselves to the display of limitless self-aggrandizement at the same time they were marketing for corporate consumer capitalism – as immortalized in “Mad Men” – the 24/7/365 messages to ‘just let go’ and indulge. The further dilemma for the corporate and rightwing cultural elites, given the broad shift of society toward greater instinctual release, was that to simply denounce the many forms of excess (including vilification of liberals) or even advocate moderation would jeopardize their commercial dominance and popular following. Unable to resist joining and inflaming rather than fighting the culture of release, they were compelled to shift strategies and agendas mid-stream.

Without benefit of a longitudinal analysis or archeology, it appears that the project of self-repression had been abdicated. The failure of a reinscribed authority generating resacralized boundaries, however, would spell not the end of the Reaction but its far more expansive and totalizing phase. The result – though few have admitted it and fewer have noticed – was far more devious and insidious: the embedding of scarcity through appropriation and redirection within the culture of release. The issue would no longer be whether limits could be reestablished but what kinds of post-liberal desires would prevail. For the Reaction, the realization dawned that certain forms of desire stifled self-development with their own loops of self-limitation, self-arrest, and addictive entrapment.

Establishing with its leverage in consumer culture a maze of empty temptations and palliation meant that such indulgence could be put forward to demonstrate its faux-commitment to the culture of release. For many reasons to be subsequently discussed, in this first historical encounter with more evolved forms of human possibility, this colossal misappropriation and misdirection has for the time being prevailed, leaving the manipulation of desire the primary strategy marking national politics. At the same time, the post-liberal vision of human transformation, of a new selfhood and a new history rooted in full self-development and human community, lurks as the ultimate reminder of the folly of the present flight from history. That story, including the contest over the future of human desire and human self-realization in the post-industrial age, comes next.

Notes

[i] Erich Fromm, Man for Himself (New York, 1947), 88-9.

[ii] See Joseph Nye, Bound to Lead: The Changing Nature of American Power (New York, 1990), 1-2.

[iii] See Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man (New York, 1992).

[iv] E.J. Dionne, Jr., Norman Ornstein, & Thomas E. Mann, One Nation After Trump (New York, 2017), 3, 1.

[v] Christopher Browning, “The Suffocation of Democracy,” New York Review, October 25, 2018, 16.

[vi] Michelle Goldberg, “Twilight of the Liberal Right,” New York Times, July 28, 2020, A23.

[vii] Ruth Ben-Ghiat, “Interview,” NYR Daily, August 15, 2020.

[viii] Rick Perlstein, “I Thought I Understood the American Right. Trump Proved Me Wrong,” New York Times Magazine, April 11, 2017.P, NYTMag, 4/11/2017; URL: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/11/magazine/i-thought-i-understood-the-american-right-trump-proved-me-wrong.html?partner=bloomberg.

[ix] Of course, the U.S. had been from the very beginning the refuge of orphans who proclaimed from both need and hope the vision of a new dispensation. Melville, Huck, Connie.

[x] Thomas Frank, What’s the Matter with Kansas? (New York, 2005), 5.

[xi] The problem with Arlie Hochschild’s effort to piece together the narrative of the reaction as merely one story among many choices has trouble coming to terms with the way stories become – and are exercised as – instruments of domination. See Hochschild, Strangers in Their Own Land (New York, 2015).

[xii] See Philip Rieff, Fellow Teachers New York, 1972); Jonathan Haidt, The Righteous Mind (New York 2012).

[xiii] See Thomas Frank, Listen, Liberal (New York, 2016).

[xiv] Lester Ward, Outlines of Sociology (London, 1923 [1897]), 109, 145; “Moral and Material Progress 1885,” [Transactions of the Anthropological Society of Washington, Vol. III, in Glimpses of the Cosmos IV], in Lester Ward and the Welfare State, Henry Steele Commager, ed. (Indianapolis, 1967), 95.

[xv] See Stuart Chase, The Economy of Abundance (New York, 1934), 139, 195-207.

[xvi] John Kenneth Galbraith, The Affluent Society (New York, 1958), 14.

[xvii] Fromm, Man for Himself, 4.

[xviii] David Riesman, “Abundance for What? (1957), in Abundance for What? And Other Essays (Garden City, New York, 1965), 292; “Work and Leisure: Fusion or Polarity? (with Warner Bloomberg, Jr.) (1957), Abundance for What?, 156-7.

[xix] Galbraith, Affluent Society, 14-15.

[xx] Robert Theobald, The Challenge of Abundance (New York, 1961), viii.

[xxi] Fromm, Man for Himself, 4.

[xxii] David Riesman, “Some Issues in the Future of Leisure (with Robert S. Weiss) (1961) Abundance, 174, 183.

[xxiii] Chase, Economy, 165.

[xxiv] Riesman “Issues,,” 175

[xxv] Daniel Bell, The Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism (New York, 1976), xx, xxv.

[xxvi] Bell, Contradictions, xxxiii-iv.

[xxvii] Daniel Bell, The Coming of Post-Industrial Society (New York, 1973), 456, 475-6, 449.

[xxviii] Bell, Coming, 446.

[xxix] Bell, Coming, 475.

[xxx] Rieff, Teachers, 21.

[xxxi] Bell, Coming, 480.

[xxxii] Rieff, Teachers, 42.

[xxxiii] Adam Seligman, Modernity’s Wager: Authority, the Self, and Transcendence (Princeton, 2000), 3, 9, 10.

James Block is the author of A Nation of Agents (Harvard) as well as The Crucible of Consent (Harvard) can be reached at jblock@depaul.edu.