If Not Now, When?: How student protest can help save US higher education

After more than 20 years of public disinvestment from social programs that help create strong, healthy, and secure young people; following five years of war-making that have, to date, seen more than 1.5 million US troops off to Iraq; and now facing the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression, it is, no doubt, a challenging time to be a young American. It is also an exciting time to be young in the United States. It is an exciting time to be young and engaged in politics. Young people from a variety of socio-economic backgrounds have been on the move since at least 2004 in the area of traditional politics, including voting and community service, as well as in the area of activism.[1] The youth vote has been in the headlines and student activist groups–local and national in scope–are reporting increased turnouts in membership and mobilizations. The U.S. student activist agenda of 2008 has been dominated by protests linking calls for an end to the Iraq war with calls for increased education funding.[2] Signals suggest that this generation is politically capable and poised to rattle the cage of American politics.

But what exactly is the source of this new youth engagement? Does it indicate a new faith in traditional politics on the part of the young or does it reflect a deeper, more widespread sense of social and political discontent? If the latter is true (as I will argue) then the question arises whether this discontent is sharp enough– or deep enough– to break out of the channels of electoral routines and demand more serious attention through the leverage of protest. Following then, on what issues can young people best use their leverage? What should they demand? Or, more tellingly, what happens if students don’t apply the leverage of protest? Might they allow themselves to be used by the Democratic Party in close contests in November which may very well turn on the new youth vote? Will America’s newly turned-on youth be able to gain specific concessions from a Party that vaguely gestures help? Might young people trustingly head to the polls, being cheered and praised along the way, without getting anything much in return? Given Obama’s seeming anti-Iraq war position, and his more generous proposals for increasing federal funding for higher education, he seems to have a clear advantage with young voters. Not incidentally, young people–across the board– are shown to be far more racially tolerant than older Americans. Obama’s cache with the young seems to suggest a place for them at the Democratic Party’s bargaining table. But can young people be assured a seat there in the event of an Obama victory? If history is any indicator, young people’s newly energized electoral influence will not alone guarantee leverage. Instead, as argued below, their electoral influence will only win them concessions if combined with strategic protest on select issues logically connected to specific institutional targets.

The argument that young people are currently well positioned to maximize their political influence through protest is connected to four related claims. First, the increase in youth participation is a result of direct appeals to the young since 2000 on the part of non-profits, schools, key segments of the music and entertainment industries, community groups and, most recently, the Democratic Party. For different reasons, these efforts sought to address the well-documented decline in youth engagement between 1972 and 2000. Second, these efforts have occurred alongside shifting material conditions for the young that have been traditional indicators for discontent. Third, deteriorating material conditions for the young have been brought on by economic policies captured in the phrases “globalization” and “neo-liberalism”. “Globalization” as such, has stripped away “public good” based regulations rooted in Progressive Era , New Deal and Great Society legislation. Likewise, globalization policies have gutted the remaining redistributive programs of the latter two eras which once promised young Americans equality of opportunity and greater security. The prismatic concerns being raised by young voters today — funding for higher education, health care, war-spending, the environment and job opportunity –reflect young people’s increasing anxiety over the future in the wake of globalization’s (neo-liberalism’s) free-market agenda.

The conditions of deteriorating material security for this generation connect to my final observation and fourth claim. Enrolled college students and marginal/potential college students seem to be waking up to politics just as significant electoral competition is breaking out within and between the major parties for the first time in more than a generation. Indeed, the young’s recent significant entry into the electoral arena seems to be a contributor to the heightened competition. Based on historical patterns, this upturn in political engagement amid a sharp shift in economic conditions and increased electoral competition suggests that conditions are ripe for the impact of student protest.[3]

This is not a new argument, nor is it a prediction. The logic traces to the work of Piven and Cloward thirty years ago in Poor People’s Movements: Why they Succeed, How they Fail (1978) where they examined popular unrest by lower-income Americans in the 1930’s and 1960’s. More recently, Frances Fox Piven applied their basic thesis to broader sectors of American society in her work Challenging Authority: How Ordinary People Change America (2006)

Three claims connected to their basic argument can be extended here: 1) the outbreak of “discontent is determined by changes in institutional life,” in which economic shifts weaken daily routines (e.g. work, school) which function to regulate civil society ; 2) “…the forms of political protest are also determined by the institutional context in which people live and work”[4]; and 3) while sharp shifts in traditional voting patterns are the first signs of discontent, “it is usually when unrest among the lower classes breaks out of the confines of electoral procedure that the poor may have some influence.”[5] In keeping with Piven & Cloward’s core argument, protest only occurs when people who otherwise acquiesce, those who accept the authority of their rulers, “come to believe in some measure that these rulers and these arrangements are unjust and wrong.” [6] I argue elsewhere that a type of theoretical lacuna exists in their work leaving the reflexive processes (both cognitive and ideological) that permit people to see conditions as wrong and “open to change,” under-explained and uncoupled from how people then translate the insights into political action [7]. More importantly, Piven and Cloward’s broad thesis is unique within the literature for its explanatory strength and power over time. Oddly, social movement writers seem to under-recognize the power of Piven and Cloward’s contribution, and resultantly the ongoing social movement scholarship aiming to understand how inchoate movements recognize and think through political “opportunities” remains muddled.[8]

In the case of contemporary student politics, Piven & Cloward’s framework is particularly revealing. While recent increases in youth voting and volunteer community service are in and of themselves praiseworthy, in keeping with Piven and Cloward I argue here that students’ greatest ability to affect economic and social opportunities for the majority of young people depends on whether or not they leverage their protest power connected to universities[9] and their networks. As with the poor– or any segment of American society that constitutes a significant voting block yet lacks money and access–protest is a critical tool of influence. using or threatening to use the power to disrupt institutions that depend in some manner upon protesters’ involvement, the logic of leverage is revealed. In her more recent work, Frances Fox Piven makes plain the earlier argument:

I use the term disruption here not merely to evoke unconventional, radical demands and tactics, but in a specific way to denote the leverage that results from the breakdown of institutionally regulated cooperation, as in strikes, whether workplace strikes where people withdraw their labor and shut down production…or student strikes where young people withdraw from the classroom and close down the university.[10]

But as Piven goes on to argue, there have been few occasions when such disruption has been capable of having impact. Such “big bang” moments as she calls them, occur when protest movements raise the ” …conflictual issues that party leaders avoid.” When protest occurs during periods when new voters or switch voters are being pursued by parties, movements can expand the scope of contention between parties and the electorate. Piven suggests:

By raising new and divisive issues, movements galvanize groups of voters, some in support, others in opposition. In other words, protest movements threaten to cleave the majority coalitions that politicians assiduously try to hold together. It is in order to avoid the ensuing defections, or to win back the defectors, that politicians initiate new public policies.[11]

For impact, protests must make the most of the climate of political competition and flux when concessions are possible. To be sure, public acts of protest generate political energy and gains not reducible to concessions alone. The mere public expression of suppressed positions upholds the right of dissent– in spirit and fact– under any conditions. Still, when protest occurs amid an atmosphere in which openings for leverage with decision-makers are evident, protest movements may be enlivened. Those openings, however. may be also be aggressively closed through the use of political repression. That decision-makers are vulnerable during periods of electoral instability, and that electoral instability is more often than not brought on by rapid economic change syncs with the likelihood that protest erupts among those who feel both ignored and insecure. That defiant movements under just such conditions have historically been the motors of democratic change in the U.S. must not be forgotten. This remains the straightforward yet elegant argument of Piven and Cloward for the last thirty years.

In keeping with this logic, students therefore wield a particular form of power in the current era. First, the surge of new young voters into the electoral arena has party strategists re-calculating numbers and re-thinking policy positions. Second, universities and colleges need young bodies for survival at least as much as the young believe they need degrees. The threat of strategic withdrawal from and/or disruption of higher education institutions remains young people’s political trump card. While the interests of non-college attending youth speak most urgently to the great threats facing increasing numbers of young Americans, protest leverage and the likelihood of political engagement is linked to participation in higher education institutions.

Certainly, the list of threats facing young people today is long and multi-layered: rising economic inequality and the looming financial collapse, social dislocations resulting from war and war spending,[12] punitive and exclusionary higher education funding policies, diminishing healthcare access, and increasingly foreboding environmental threats dot the horizon. But few of these concerns provide young people a platform and logic for protest in the way that higher education policy does. If it is true, as I suggested at the top of this essay, that young people’s leverage rests with “strategic protest on select issues logically connected to specific institutional targets” then the rapidly deteriorating chances among the young for quality, higher educational attainment provides both motive and context for protest.

The past two decades of high school graduates have been grappling with increasingly prohibitive higher education costs alongside successive waves of gutted financial-aid programs and attacks on affirmative action.[13] Inequality in admission and retention is rising, student and family indebtedness has spiked, and job opportunities for graduates are plummeting. To add to this, the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) looms on the horizon, and promises to sever the higher education industry from remaining government protections and academic regulatory practices rooted in traditional notions of academic autonomy and the public good.[14] In an uncharacteristically sharp warning, a spokesman for the American Council on Education (ACE) stated that the higher education provisions in the WTO-sponsored GATS are “the higher education equivalent of the asteroid hurtling toward earth that people aren’t really aware is out there, or of the consequences once it hits.”[15] For those who are paying attention, it is understood that the unfettered global market trade in higher education services under GATS will further threaten the self-regulatory capacities of American universities and will further reduce their socio-economic re-distributive functions. [16]

All things being equal?: Political Engagement, Educational Attainment & Rising Inequality

Interestingly, data from the 2004 national and 2006 midterm elections showed, uncharacteristically, that significant increases in youth participation in those years cut across class, race, ethnicity, gender and geography (urban, suburban and rural).[17] Indeed, the youth vote rose 11% in 2004 for college-attending youth, and 9% for non-college- attending youth–overall, 49% of eligible 18-29 year olds turned out. Outreach to youth of all incomes was particularly poignant in the 2004 campaign season as community-based organizations, scattered secondary and post-secondary initiatives and music-industry related campaigns all combined to urge young people to register, vote and be heard.[18] More recent reports, however, demonstrate that in the midst of a broad rising trend in engagement, a new-old “civic engagement gap” is emerging among youth based on class and educational attainment.[19] Stubbornly and predictably, the class/education gap is also a race and ethnicity gap between better-off, predominantly white youth on the one hand, and less well-off, disproportionately African-American and Latino youth on the other. Whereas in 2004 and 2006 the electoral surges among the young were fairly even for college and non-college youth, the recent super-surge of young voters in 2008 primaries and caucuses (with youth turnout, doubling, tripling and even quadrupling in some contests[20]) shows a distinct divide (Figure 1). Moreover, Meira Levinson, of the Center on Information and Research on Civic Learning, reports a salient, “civic achievement gap between non-white, poor, and/or immigrant youth, on the one hand, and white, wealthier, and/or native-born youth, on the other. Young people (and adults) in the former group demonstrate consistently lower levels of civic and political knowledge, skills, positive attitudes, and participation, as compared to their wealthier and white counterparts. As a result, they face serious political disadvantages”.[21]

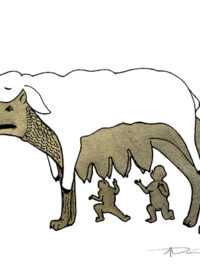

Figure 2

This trend-within-a-trend is troublesome, telling and open to transformation. Its potential for transformation rests on the shoulders of this demographically interesting generation of young Americans amid conditions historically associated with student protest impact. Whether or not conditions will prompt enough young people to see change through protest as viable and compelling remains to be seen.

This trend-within-a-trend is troublesome, telling and open to transformation. Its potential for transformation rests on the shoulders of this demographically interesting generation of young Americans amid conditions historically associated with student protest impact. Whether or not conditions will prompt enough young people to see change through protest as viable and compelling remains to be seen.

What’s so interesting about this generation?

Protest movements are never the straightforward product of structural strain, political opportunity or changing demographics. Yet the possibility of significant numbers of people seeing unjust conditions as open to change, and purposively setting out to create that change is mediated by these factors. In the case of U.S. youth, strain (increasing inequality), conditions of electoral competition and compelling demographics all set the current stage.

First, young Americans are numerous; youth (18-29 year olds) now make up the largest share of the population since the baby boom, and the trend shows strength.[22] In 2006, there were just over 32 million 18-25 year olds and 74 million 0-17 year olds. In 1968, by way of comparison, there were 23 million 18-25 year olds and 70.5 million 0-17 year olds. While voting age youth made up a larger share of the electorate in 1972 (24%), 18-29 year olds have been a steadily increasing share of the eligible voting population since the 1980’s when birth rates began to rise again following a lull. Youth now make up 21% of eligible voters. This makes them twice as numerous as the highest voter turnout group, 66-77 years old.[23]

Second, young Americans are more diverse than older populations with respect to race and ethnicity. The Pew Foundation funded Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning (CIRCLE) reports :

Between 1976 and 2006, the percentage of young residents who are white has steadily fallen from approximately 79% in 1976 to approximately 62% in 2006. The percentage of young residents who are Latinos grew 10 percentage points from 8% in 1976 to 18% in 2006.[24]

Connected to their post-sixties diversity, youth today prove to be more racially, ethnically, religiously and politically tolerant than their counterparts 40 or even 20 years ago. They have broader attitudes on race, homosexuality, civil liberties, immigrant status and religious or political affiliation. Whether the data comes from the Higher Education Research Institute’s “Freshman Survey,” the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning’s various studies, or from Russell Dalton’s presentation of 2004 General Social Survey and the International Social Survey Program[25]The Good Citizen (2008), the data shows increased tolerance is a trait of the current and emerging generation of young people. Dalton also argues that younger generations exhibit a far more engaged citizenship which includes higher levels of support for government spending[26] and higher levels of protest activity (particularly when Internet and consumer actions are included[27] than older generations.

Additionally, immigrant youth make up the largest share of the youth cohort since 1920. In 2006, 13.3% of 18-25 year olds were born outside the U.S.; another 6.5% were born to foreign-born parents. (See Figure 2).

Figure 2

What makes this compelling in relation to student discontent? First, the fastest growing youth populations happen also to be among the lowest income groups, thus indicating the level of hardship shaping current generations of the young. The dream of post-secondary education–and the attendant aspirations of economic mobility and traditional political influence– are increasingly closed to low-income youth, particularly from immigrant communities. In combination with declining higher education enrollments of African-American and low-income whites (discussed below), the lack of higher education opportunity for this fast-growing section of American youth is politically provocative. Indeed, a 2006 study showed that, while Latino youth are much less likely to be engaged in traditional politics, more than 25% report having participated in a recent protest.[28] When understood in the context of the powerful civil rights demonstrations within immigrant communities in 2006 and 2007 –including school walkouts by middle and high school students–a powerful trajectory of protest may be nascent.

The pattern of disinvestment from American youth is widespread, though harder felt for some. Little in US spending patterns over the last 30 years suggests public support for young people. Bush’s 2009 proposed budget continues the trend of dis-investment in American youth and will only exacerbate rising poverty among youth and children. According to the Children’s Defense Fund, 1.2 million more children are living below the official U.S. poverty level since Bush took office. In the 3.1 trillion dollar proposed 2009 budget, another round of cuts are slated for Medicaid, vital nutrition programs, food stamps, WIC, and Section 8 housing subsidies. Marion Wright Edelman of the Children’s Defense Fund has commented:

It is astonishing that Mr. Bush is asking Congress to eliminate 47 programs in the Department of Education that would disproportionately affect low-income and minority at-risk children, including for example Supplemental Opportunity grants that benefit college students from America’s poorest families (Press release, March 2008)

Much about youth security can also be gleaned from the minimum wage, slotted to rise this year to $6.55 per hour. Even at the increased level, it only earns 40% of the official poverty level for a family of four.way of comparison, the 1968 minimum wage earned 90% of the poverty level, which adjusted in real dollars would be equivalent to $9.50 per hour today. Whether among the minimum wage-earning youth, or among the increasing numbers of children living in a home earning at the minimum-wage level, economic conditions have deteriorated for youth since 1968.

Will this spur an effective protest movement? What issues animate student complaints? Where, how and on what issues can students have an impact?

If, as Piven and Cloward suggest, discontent and leverage are connected to the institutions that shape daily life, the fulcrum of student power seems to rest with schools and institutions of higher education. When assessing the broad economic shift dubbed “globalization” and its impact on higher education policy in the U.S., there seem to be much to protest. Indeed, U.S. students can learn from watching their counterparts in Canada, Australia, France, Italy, Germany and other EU nations who have taken to the streets in protest of both the GATS inspired “Bolgona Process” and GATS itself.[29] U.S. students face greater obstacles to higher education access than their EU counterparts and risk even greater hardships under new policies. The U.S. gap between level of hardship and level of protest in this area may point a way for the US student movement agenda.

Conditions for student protest? Globalization, Higher Education and Rising Inequality

The great challenge of this generation of young activists will be the development of strategic protest campaigns that leverage the spatial and educational-attainment advantages of college-attending youth in the interest of those youth who are increasingly at the margins and locked outside of higher education. The current student protest focus on stopping the war and increasing funding for higher education suggests they are conscious of the stakes. Indeed, the policies responsible for the rising inequality in access to higher education are reflective of the broad array of policies (combining neo-liberal initiatives with a war-economy) that threaten the general welfare of this generation. Globalization as such is rooted in an ideology committed to the privatization of public goods and services previously won by generations of democratically committed citizens. The acceleration of neo-liberal education policies under GATS promises to further the privatization agenda and worsen conditions for the growing ranks of low-income young Americans. Given the demographic make-up of the U.S.’s 17 million higher education attendees– 80% of whom attend public, state and community colleges– the potential for a democratic and class-conscious student movement is better today than in the recent past.

The ideology of privatization is affecting every level of our culture. The politics and the decisions which drive and enforce this agenda are controlled by governing bodies that are not elected, do not have young people’s best interests in mind and are not accountable. Still, the market-based and market-driven initiatives of international bodies like the WTO, the World Bank and the IMF in some form end up before national assemblies like the U.S. Congress. In this respect, the increased competition in the electoral arena, and the myriad of opportunities for youth there is meaningful. The national election cycle it follows, still matters and sets the stage for young people to gain the attention of law-makers.

The ideology of privatization is transforming higher education systems around the world. Whether we are talking about France, South Africa, China, Italy, Singapore, Australia, or the U.S., public higher education systems and institutions are being pressured and compelled to adapt to market logic and market dynamics. According to the ACE associate director of government relations, GATS will mean that: “Some bureaucrat at the World Trade Organization could be making decisions that overturn the judgement of the U.S. Congress or state governments.”[30]

Scholar Fazal Rizvi has noted that the broad principles of privatization take at least four forms: 1) the transfer of ownership of public institutions; 2) the shift of public operations to the private sector; 3) decreased public investment and increased government support for private interests; and 4) the outsourcing of functions and services, including anything from university food services to research and teaching, to the private sector.[31] These principles are changing the American university in fundamental ways that require the abandonment of its long-standing, hard-won democratizing functions.

As Donald Heller has argued, decreased public investment in U.S. education in the current era marks a break with a public rationale dating back to the post-Civil war period in which federal and state investments in higher education were seen to have a “return.”[32] It is widely observed that there have been three major moments in which this public rationale was forged: 1) the granting of public lands to the states for higher education purposes under the Morrill Acts of 1862 and 1890, 2) the Serviceman’s Readjustment Act of 1945, and 3) the Higher Education Acts of 1965-1980 which established Pell Grants. In each case, public investment in higher education was expanded, signaling that university education was not the prerogative of upper strata Americans, but something to which the masses were entitled. Indeed, the public rationale that was forwarded by those movements and advocates who fought for and won this legislation had three components. The compact suggested that public investment in higher education would: 1) a produce a more skillful and competitive workforce, 2) increase economic mobility, and 3) contribute to a more efficacious citizenry.[33] That higher education was understood as an industry did not preclude a simultaneous understanding of higher education as a democratic social good deserving of public investment.

From the Civil War until 1980, tuition was either a negligible or non-existent source of higher education’s overall revenues in the U.S.looking at higher education’s revenues today, we see how dramatically the federal and state contributions to higher education revenues have declined. Indeed, the federal share of higher education revenue (public and private) has declined from a high of 20% in the mid-1960s through the 1970s, to around 11% today. More dramatic is the decline in states’ share of of higher education revenues; these have declined from a high in 1980 of 34% to around 23% today.[34] For the first time since before the Civil War, tuition and fees make-up the largest share of higher education revenues.

While private financial contributions have kept enrollments steady and growing over the last 20 years (despite predictions to the contrary), they have caused student and parent indebtedness to increase dramatically and dangerously. Indeed, as economists seek to explain the demand side of the “bad mortgage” crises, big arrows should point to the excessive re-financing by families of their homes in order to meet skyrocketing tuition costs. Certainly, the greatest beneficiary of the public disinvestment from higher education has been the banking/loan industry. And while taxpayers are being bound by Congress to bail out predatory banking/loan industry, no one prepares to assist those ordinary Americans crushed by debt connected to higher education. To more fully understand the family burden of financing higher education, a look at cost to income over a twenty-year period is helpful. At St. John reports, mean income in the U.S. increased 150% in the period between 1980 and today, while tuition at public four-year colleges increased 517%; in the same period community college tuition rose 387%.[35] Capped Pell Grants have now lost their purchasing power with maximum grants not able to keep lower-income youth in school. As states and institutions respond to the loss of need-based aid by introducing merit-based aid, lower-income students are further disadvantaged.

Despite statistical error and misinformation on the part of the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), Edward St. John and Ontario Wooden have demonstrated with NCES’ own data, that “[t]he decline in federal grant aid, coupled with shifts in state funding for higher education, have fueled a new period of unequal opportunity. There is substantial evidence that low-income, college-qualified students have been left behind in large numbers.”[36] Little is being done in higher education circles to publicize the fact that the empirically pronounced access gaps–and all that brings–promise to increase under the General Agreement on Trade in Services’ higher education provisions. [37] Little in the way of serious public education or opposition is underway. When considered alongside young people’s stakes in the policies and their rising interest in politics the stage may be being set in the U.S. for a reassertion of the old compact.

Certainly the campaigns like those developed by the “Books Not Bombs” and “Tent State University” coalitions are promising. Yet given an emerging class-based gap in youth participation, the political character of such campaigns–both strategic and ideological– remains unclear. How far will students and allies be willing to go in pressing for equal access to higher education? Will demands be based on middle-class relief or will the majoritarian interests in universal access to higher education shape their imagination?

In media coverage, the new youth engagement, to the extent it is covered at all, is portrayed in very pedestrian terms. Many rightly point to increases in civic engagement among the young as evidence that a variety of civic initiatives in public schools and colleges are taking hold. While initiatives vary from thin neo-liberal/neo-conservative calls for volunteerism to more substantive lessons in the democratic arts and community problem solving, research shows that opportunity for exposure to civic education in high school is much higher for those attending schools in white, wealthier districts. To be sure, while any improvement in youth voting and engagement is cause for some degree of celebration, the re-inscription of the historic U.S. equation of property and political voice seems an unfortunate trajectory of much of the new civic education. Aimed as it is at those more likely to participate in the first place, the bias under new conditions produces tensions that might possibly produce broader questioning. The problem remains that as higher education become less equitable, so does the polity. And while educational access cannot be considered a harbinger for economic justice, its absence insures its opposite. What interventions can be made?

This can best be answered by considering what options have been successfully employed historically under related conditions? The answer is protest: disruptive, persistent, strategic student protest. Indeed, protest by students and potential students can have its greatest influence when aimed at higher education policy using clever institutional strategies in university settings. Examples of sucessful campus-based protests can be found in the 1980’s Anti-Apartheid movement and the 1990’s Student Anti-Sweatshop campus movement. In each case, students consciously utilized the local protest strategy of withdrawal and/or disruption to pressure universities to then use their institutional leverage in other specified arenas (university financial investments in Apartheid South Africa and university purchasing power in the college apparel industry, respectively).

While local university settings provide an obvious starting place, the crisis in higher education today coupled with the deepening economic crisis suggests national targets such as the Department of Education and the US Trade Office. In this case, young activists today might greatly benefit from examining the often ignored example of student and youth protests in the Great Depression and New Deal Era. As Robert Cohen carefully documents, more than 3000 youth and students, seeking to “dramatize the economic hardships of youth in the Depression Era” marched on the White House in February of 1937 as part of a three day “Youth Pilgrimage for Jobs and Education”. For, the pilgramage, youth leaders collected nearly one million signatures in support of the American Youth Act which outlined generous federal aid for youth jobs and education. Student “…leaders brought their advocacy of this bill directly to President Roosevelt”[38] and met with First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt who served thereafter as a liason between the White House and the student movement. While it is difficult to imagine such a situation arising under the Bush Administration, it is quite another to imagine such an encounter with an Obama Administration. The history of student protest has some rich lessons for the today’s youth.

While voting can create limited pressure, students’ interests are disadvantaged in the electoral process in the absence of a threat of disruption. Student lobbying efforts are even more dis-advantaged under current conditions due to the dramatic transformation of higher education policy circles since the mid-1990’s. Policy scholars now refer to the “collapse of the community” and a “broken compact” in higher education circles, which have abandoned the once foundational notion that public investment in higher education is a public good. Michael Parsons has observed that the near thirty-year liberal consensus among higher education policy actors “came to a swift end” in the 1990’s as neo-liberals and neo-conservatives enforced a “more primitive form of power” resulting in a move “away from equity to privatization.”[39]

Precisely as conditions for equitable access threaten to worsen under GATS, the higher education policy community in DC is least able and/or willing to defend public higher education. Conditions under globalization and neo-liberal policy in the field of education challenge student activists to look beyond the politics of service, parties and interest groups. The era in which student interest groups like United States Student Association (USSA) or the state level organizations like the New York-based SASU (Student Association for the State University) might have an impact through lobbying has passed. The breakdown of the “equity” consensus that was forged among higher education policy interest groups following the 1965 HEA has been abandoned in favor of privatization policy.[40] Under such condition, protest becomes not only important, but imperative.

Conclusion:

Under the conditions of globalization, excessive U.S. war spending, and pending economic and environmental disasters, serious threats press in on the lives of young Americans. At the same time, civic, electoral and protest levels among the young are on the rise. Given the size, diversity and economic characteristics of young Americans, student demand for increased public support of higher education is both timely and needed. Ideally, it can imagined that a 21st century version of the American Youth Act of 1937–backed by protest and petitions–might help ameliorate the conditions of increasing hardship facing the majority of Americas young. Historic patterns suggest that the potential of the young to influence decision-makers on this agenda lie with breaking out of the bounds of electoral routines. At a time of increased electoral competition among and within the major parties student protest is more likely to be heard. But the window of opportunity may not last. The rising costs of higher education in a time of increasing economic turmoil, hardship and indebtedness promise to worsen even as GATS looms. Conditions for funding and equality of access promise to worsen. The crises further squeeze recent graduates and promise to exacerbate the already high attrition rates among African-American, Latino and lower-income whites. For an increasing number of young Americans, the economic risk of higher education is simply insurmountable. In making the transition out of high school, the current market cannot sustain young people who will be increasingly turned away from higher education institutions, and courted by the military or the criminal justice systems. In such a context, youth protest for decent jobs and universal access to higher education offers a promising horizon. The signs for a serious U.S. student protest movement seem boldly written on the wall. The old phrase re-appears and gains new significance: If not now, when?

[1] Numerous publications of the Center for Information on Research and Civic Learning (CIRCLE) detail the empirical foundations of these trends. Additionally, a spate of diverse scholarship from Russell Dalton’s The Good Citizen: How A Younger Generation is Reshaping American Politics (CQ Press, 2008) to Michael Connery’s Youth to Power: How Today’s Young Voters are Building Tomorrow’s Progressive Agenda (IG Press, 2008) debate the meaning of the numbers.

[2] Coordinated student mobilizations in the spring of 2008 marked the 5th anniversary of the Iraq war with “Funk the War” protests on over 25 campuses nationally. A widely representative “Books Not Bombs” national coalition has been instrumental in shaping campus anti-war walkouts, rallies and teach-ins since 2003. Additionally, 30 campuses nationally and five internationally participated in the week-long “Tent State University” campaign calling for increased education funding and an end to the war. Tellingly, multi-issue left groupings like the new SDS and the Young Democratic Socialists have reported significant increases, with YDS membership tripling in the past 2 years.

[3] See Piven & Cloward, “The Structuring of Protest” in Poor People’s Movements (1978)

[4] ibid., p. 14.

[5] ibid., p.15.

[6] ibid., p.4

[7] see Christine Kelly, “Prospects for a More Reflexive Movement Ideology” in Tangled Up in Red, White & Blue: New Social Movements in America (2001).

[8] Despite the recent collaboration between leading social movement scholars McAdams, Tilly and Tarrow in the collection Dynamics of Contention (2007), little progress has been made in clarifying the relationship between the structural and institutional conditions shaping protest and the reflexive capacities of movements.

[9] Certainly secondary schools are important and have over time proved to be sites of protest. At the same time, protest activities of secondary students are more constrained due to legal status, and family and school control.

[10] Frances Fox Piven, Challenging Authority: How Ordinary People Change America (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2006) p. 21.

[11] ibid., p.104

| [12] In a January 2007, Professor Linda Blimes of the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard published “Soldiers Returning from Iraq & Afghanistan: The Long-Term Costs of Providing Veterans Medical Care & Disability Benefits,” where she reports that operations in Iraq (and Afghanistan) present the highest wounded to fatality ratio of any war in U.S. history. Using official statistics, Blimes reports a startling 16:1 ratio as compared with past highs of 2.6 and 2.8 in Korea and Vietnam respectively (pp. 1-2.) Blimes urges reform and expansion of veterans’ medical care and disability services to absorb the sharp increases. More recent media reports have sought to correct official numbers such as those used in Blimes report. After re-working Pentagon data retrieved through FOIA requests in late 2007, more than 20,000 returning veterans with debilitating brain injuries (resulting from repeated exposure to bomb blasts) were found to have been left out of the official wounded tallies (Greg Zoroya, USA TODAY, November 30th 2007). With more than 1.5 million troops ( average age 25) having served to date, the social costs of war on this generation have yet to be assessed. | |||

[13] For a discussion of the impact of the decline of federal aid see James C. Hearn and Janet M. Holdworth “Federal Student Aid: The Shift from Grants to Loans” in Public Funding of Higher Education, eds. Edward P. St. John and Michael D. Parsons (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006).

[14] For general background information on the implications of GATS on higher education policy, see Roberta Malee Bassett, The WTO and the University: Globalization, GATS and American Higher Education (New York, Routledge, 2006).

[15] Andrea Foster, “U.S. Position in Trade Talks Worries College Groups,” Chronicle of Higher Education, Vol. 53, Issue 30. P.A29. March 30, 2007.

[16] Roberta Malee Bassett, The WTO and the University: Globalization, GATS and American Higher Education, pp. 53-62.

[17] See Mark Hugo Lopez, Emily Kirby and Jared Sagoff, “The Youth Vote 2004,” Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning (CIRCLE), July 2005. Also see, Kirby and Marcleo, “Young Voters in the 2006 Elections,” CIRCLE, December 2006.

[18] “Rock the Vote” rap and rock artists toured major cities across America, while significant press attention surrounded Sean Combes ‘ potent “Vote or Die” ad campaign. These high-profile campaigns eased the work of community-based organizations like ACORN and complemented the patchwork of post-secondary campaigns (such as the American Association of State Colleges and Universities’ American Democracy Project) and resulted in sharp increases in youth registration and voting. State parties were oddly missing from the youth registration effort.

[19] See Meira Levinson, ” Working Paper 51: The Civic Achievement Gap,” CIRCLE, January 2007.

[20] See https://www.civicyouth.org/PopUps/FactSheets/FS08_supertuesday_exitpolls.pdf; March, 2008.

3 Ibid.

[22] See Mark Lopez and Karlo Barrio Marcelo, “Youth Demographics” Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning, November 2006.

[23] Ibid.

[26], ibid, p 65.

[27] ibid, p.109.

[28] Mark Lopez et al, “The Civic and Political Health of a Nation”, CIRCLE, 2006.

[29] UK Indymedia, “Education: protests in Europe,” https://www.indymedia.org.uk/en/2003/11/280435.htm, November 2003. For more general information linking national websites reporting student and youth protests of GATS visit https://www.education-is-not-for-sale.org

[30] Andrea Foster, “U.S. Position in Trade Talks Worries College Groups”, Chronicle of Higher Education, Vol.53, Issue 30, p. A29. March 30, 2007.

[31] Fazal Rizvi, “The Ideology of Privatization in Higher Education: A Global Perspective” in Privatization and Public Universities, eds. Edward P. St. John and Michael Parsons (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press), 2006, pp 67-68.

[32] Donald Heller, “State Support of Public Higher Education: Past, Present and Future” in Privatization and Public Universities, eds. Donald Priest and Edward P. St. John (2006).

[33] Edward St. John and Michael D. Parsons, “Introduction” in Public Funding of Higher Education: Changing Contexts and New Rationales, eds. St. John and Parsons, (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 2004).

[34] See, Edward P. St. John and Ontario Wooden, “Privatization and Federal Funding for Higher Education” in Privatization and Public Universities (2006)

[35] see Edward St. John “Privatization and Federal Funding For Higher Education” Privatization and Public Universities (2006)

[36] Ibid, p. 59.

[37] See Roberta Malee Bassett, The WTO and the University: Globalization, GATS and American Higher Education (New York: Routledge Press), 2006.

[38] Robert Cohen, When the Old Left Was Young: Student Racicals and America’s First Mass Student Movement, 1929-1941 (New York: Oxford University Press), p.191.

[39] See Michael D. Parsons, “Lobbying in Higher Education: Theory & Practice” in Public Funding of Higher Education: Changing Context and New Rationales, eds. Edward St. John and Michael Parsons, (Baltimore:John Hopkins Press), 2004; p. 215.

[40] ibid.

NOTE: Special thanks to Eliot Katz and Frances Fox Piven for editorial suggestions and comments on a draft. An early version of the paper was delivered 4/11/08 at the “Expanding Inclusion in Higher Education” conference sponsored by the Ford Foundation and Howard Samuels Policy Center, CUNY.