Political Violence Against Women: A Form of Misogyny?

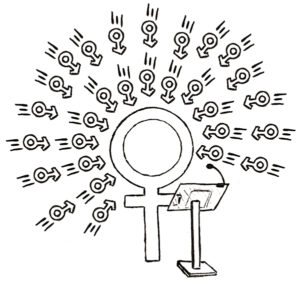

Misogyny — contempt for women — is as old as patriarchy. However, it has taken new forms globally as women have increasingly gained prominence in fields like politics. Assertions of women’s power in domains that were traditionally the purview of men have given rise to new anxieties among some men, resulting in verbal, digital, and sometimes even physical violence directed at women politicians the world over. This misogynistic harassment and abuse creates an exclusionary environment for women in politics and women marginalized by race, sexuality, age, and other differences.

However, political context matters, and these attacks are not happening for the same reason everywhere. Some have described these trends as “backlash,” or as the product of right-wing tendencies in democracies. Misogyny is not just a nasty sentiment: it is undergirded by political and economic factors, particularly when it can be seen as a social phenomenon. However, there is a wide variation in explanations for such attacks on women politicians, depending on the context.

Women have doubled their representation in legislatures globally to 26.7% since 2000, according to the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU). Today, there are 29 women heads of state or government (15%). At least 59 countries have had a woman leader to date. The numbers slowly increased after 1990, when only nine countries had women heads of state or government.2023, women made up almost 23% of the cabinet ministers, with 13 countries having reached or surpassed 50% women cabinet members. Although Nordic and some European countries have historically had among the highest levels of female representation, today, countries like Rwanda, United Arab Emirates, Cuba, and Mexico are found topping the charts. Although these numbers in most parts of the world do not come close to equitably representing women, who make up half the world’s population, these increases have begun to change the face of politics in tangible ways.

As women have made political gains, violence against political women has increased. Some have argued that while women are being voted into many new positions, various men have felt that they are being eased out of domains they traditionally dominated. And so, we are seeing a simultaneous increase in physical violence, verbal intimidation, and sexual harassment of women politicians. It has also involved psychological violence, including online harassment by trolls, who use sexualized graphics and gendered insults and threats to bully women in politics. These tactics are analyzed in a 2020 book by Mona Krook, Violence against Women in Politics. But feelings of increased exclusion by men is only one explanation for these attacks on women. While increases in violence against women politicians is a global phenomenon, the reasons are context-dependent.

A Global Phenomenon

The phenomenon of women politicians being attacked is global. According to the Inter-Parliamentary Union’s landmark survey (2016), almost all female legislators have encountered psychological harassment during their tenure in parliamentary roles, one-quarter have been subjected to some form of physical violence, and one-fifth have experienced various instances of sexual violence.[1] A 2023 survey by MeTooEP in the European Parliament similarly found that of the 1,001 respondents, almost half had experienced psychological harassment, 16 percent suffered sexual harassment, and 7 percent faced physical violence. Surveys of parliaments in the Netherlands by Utrecht University in 2023 and by the Australian government found similar results.

At one extreme, we have countries like Afghanistan, where a women lawmaker, Mursal Nabizada, was killed in January 2023 because she protested the Taliban administration’s restrictions on women since women no longer are allowed to participate in politics.[2] Several women politicians have been killed in Afghanistan simply because they were women seeking office. However, many countries where women politicians are being targeted have actively promoted women leaders and have some of the highest rates of political representation of women in the world.

Even in Finland, the first country in the world to seat women in parliament as early as 1907, women politicians have been attacked. Sanna Marin faced extreme misogynistic abuse while she served as Finland’s Prime Minister from 2019 to 2023. She was not alone. A report from the NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence highlighted a distressing trend in which the five most targeted ministers, all female, experienced a barrage of misogynistic abuse that targeted their values, demeaned their decision-making abilities, and questioned their leadership skills.[3] The report noted that “a startling portion of this abuse contained both latent and overtly sexist language, as well as sexually explicit language.” This kind of trolling has far-reaching consequences. A study conducted in 2019 revealed that 28 percent of Finnish municipal officials subjected to hate speech expressed reluctance to participate in decision-making processes as a direct result of these attacks.

The abuse, however, is not limited to anonymous internet trolls. Moreover, it is often directed at young women. Marin, who was the youngest person to hold the position of prime minister in Finland, faced a torrent of criticism when someone surreptitiously leaked photos of women drinking and enjoying themselves at a party she hosted in her home. She was forced to take a humiliating drug test to allay criticisms that followed. Men rarely receive this level of condemnation.

Iiris Suomela, of the Green League and the youngest parliamentarian in Finland at the age of 25, pointed out that the “behavioral norms for young women are very strict. When a [young] female minister swears on TV, there is a massive uproar, but when a middle-aged man from the other side of the political spectrum uses abusive language, or is even suspected to have committed a crime, it does not cause a similar reaction.” Suomela was referring to an incident where the Left Alliance Li Andersson described an opposition politician as talking “bull. . . .” Andersson had taken over her position as Minister of Education in 2019 at the age of 32. At the same time, several male members of parliament with the far-right Finns Party were under investigation or had been convicted for “incitement against an ethnic group.”[4] This double standard illustrates how there can be two sets of rules for men and women in politics.

In the United States, some of the attacks we are witnessing are tied to the rise in right-wing extremism. We have become all too familiar with reports of right-wing violent attacks aimed at politicians like Rep. Gabby Gifford, Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, former Speaker of the House, and Rep. of California Nancy Pelosi. Rep. Paul Gosar shared an animated video of him killing Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. More recently, in October 2023, Florida GOP Rep. Ted Yoho accosted her on the Capitol steps when he called her “disgusting,” “crazy”, “out of her mind,” and “dangerous.” She countered him by saying that he was being rude. Later in front of reporters, he called her a “f. . . ing bitch.” Many have pointed to the influence of former President Donald Trump and the MAGA movement in helping normalize some of this violence. In the United States, we have also seen the rise of the “outrage industry” of talk radio, podcasts, blogs, and other forms of political talk, amplified by social media, that has escalated feelings of anger, according to Sarah Sobieraj, author of Credible Threat: Attacks Against Women Online and the Future of Democracy. This discourse has heightened the danger that people will engage in real-world attacks, with particular consequences for women and ultimately with implications for democracy, human rights, and political inclusion.

Authoritarian Patterns

In authoritarian environments, there are additional motivations behind assaults targeting women. My research into authoritarian regimes shows that the same regime that enacts legal and constitutional measures to safeguard women from violence can employ state power to violently suppress women who protest state policy or belong to the opposition. The same regime may implement quotas as a strategy to enhance female inclusion yet also employ tactics to exclude women who belong to opposition parties. They do so in ways that go well beyond the ordinary tactics of opposing parties.

The Rwandese government has the highest percentage of women in parliament in the world (61%), yet it suppressed and imprisoned two women who ran for president on trumped-up charges and carried out a smear campaign against them. One businesswoman, Diane Rwigara, who had been outspoken against the Kagamé regime, stood as an independent candidate in the 2017 Rwandan presidential elections. Soon after she announced her candidacy, nude photos of her were circulated to the press in an effort to intimidate her. Rwigara, her mother, and four other associates were arrested and charged with “inciting insurrection.” She was later acquitted in 2018, possibly as a result of international pressure, but her arrest had a chilling effect on other would-be presidential aspirants and those in the political opposition, particularly women. Earlier, in the period leading up to the 2010 presidential elections, an opposition party leader, Victoire Ingabire Umuhoza, was prevented from running. In October 2012, she was sentenced to fifteen years imprisonment for “conspiracy against the country through terrorism and war.” She served an eight-year sentence, five of which were in solitary confinement. Rwigara and Ingabire Umuhoze were singled out as a warning to other women not to challenge the president and his ruling party. Thus, women can be involved in politics as long as they are aligned with the ruling party.

This pattern is evident in other African authoritarian countries but for a variety of reasons. Many one-party countries transitioned to multiparty systems after the 1990s, forcing ruling parties to look for new ways to maintain vote share. My current research shows that many of these countries adopted reserved seat systems, which ostensibly allowed women from any party to run for specific seats that only women could contest as a measure to increase female representation. There are other types of quota systems, including legislated quotas and voluntary party quotas. However, only authoritarian countries in Africa have adopted reserved seats because it allows them to more easily control the women who run for these seats in ways that are prohibited by voluntary party quotas or legislated quotas. In Uganda, for example, the ruling party, the National Resistance Movement (NRM), tries to control the women who are elected to the reserved seats set aside for women by aggressively decampaigning, coopting, and funding opposition women who run for these seats. The NRM has used these seats, among a variety of other tactics, to maintain vote share after the country went multiparty in 2005. Women opposition leaders have been publicly stripped, arrested, sexually harassed, threatened with murder, and even poisoned, creating strong incentives for women to run with the ruling party or not to participate in politics at all.

As one woman opposition leader said to me: “Women are a bit cautious. They’re thinking, ‘Okay, I really want to participate, but not in this environment. I have children’.” Yet this is a country where women politicians who support the ruling party have been welcomed. Uganda has a woman vice president, the second in its history. The country has a female prime minister, deputy prime minister, Speaker of the House, and Government Chief Whip in Parliament. Five out of the 11 Supreme Court justices are women. Women hold 47% of the seats in local government, 43% of the cabinet posts, and 35% of the seats in parliament. In other words, the government has promoted women leaders while targeting women in the opposition. This is not simply misogyny, but a form of targeted repression found in autocracies.

The same kind of state-induced violence is evident in Zimbabwe, where female opposition leaders are singled out for repression not only through extra-legal activities but through the judicial system itself. On one hand, Zimbabwe has passed laws promoting women’s involvement in politics and against gender-based violence. On the other hand, there is a disturbing pattern of repression and violence against women who demand reforms that are considered “undesirable.” This arbitrary and unpredictable repression casts a chilling shadow over women’s mobilization efforts and the issues they champion. A gender specialist lecturer succinctly summed it up to me recently by stating, “The government has implemented coercive measures to control women’s movements, instilling fear of entering politics and assuming leadership roles.”

In 2020, opposition leaders Hon. Joana Mamombe, Netsai Marova, and Cecilia Chimbiri were arrested on three separate occasions for protesting the government’s handling of COVID-19 policies, including issues related to food scarcity and social support. They endured physical and sexual assault, and later, they were charged with disseminating false information about their abduction and torture by suspected state security agents in 2022. All three women were affiliated with the Citizens Coalition for Change (CCC), formerly known as the MDC Alliance. Marova, one of the women, emphasized, “We are dealing with an exceedingly unpredictable government and a capricious judicial system. We can never be certain of the outcome” (Oppenheim 2022). In 2023, the High Court acquitted Mamombe and Chimbiri, while Marova had sought asylum in exile.

Pervasive Violence

In some countries like Kenya, where violence against male politicians is already prevalent, violence against women is an extension of violence between male politicians. It involves attacks by politicians from all parties who feel particularly threatened by another candidate. Many Kenyan political leaders employ armed militias or hired individuals unleashed during elections to intimidate and harass their opponents and for self-defense. As newcomers to politics, this becomes a real impediment to women’s participation.

I carried out research in Kenya when there was a significant increase in women’s representation following the passage of the 2010 constitution, which included affirmative action provisions for women’s political representation. As a result, in the 2013 elections, the percentage of women rose in the Cabinet from 12.5 percent to 33 percent, in the legislature from 7.5 percent to 19.4 percent, in the county assembly to 52 percent, and in the Supreme Court to 29 percent; the Appeals Court from zero to 31 percent; and in the High Court from 40 percent to 49 percent. But as women got involved in politics, like men, they became victims of violence.

Interviews during 2014 in Kenya revealed that the primary factor influencing women’s participation in political leadership was the pervasive threat of violence and actual incidents of violence experienced by women who aspired to be in politics or who held leadership positions. Nearly every female politician I interviewed at the county and national level — sixteen in all — shared personal experiences of violence directed at themselves but also targeting their family members and supporters. These women faced intimidation, property damage, and verbal abuse. Most of these incidents occurred before the elections, but some continued even after women took office.

For instance, Caroline Owen, the Speaker of the House and Kisumu North Ward Representative received death threats through leaflets scattered along her path to the local market. Another woman candidate I interviewed tragically lost her 5-year-old son due to election-related violence. Some women were hospitalized, others were subjected to sexual assault, and some had their family members threatened. Such violence creates extreme disincentives for newcomers to enter the political arena.

While such political violence was a common practice among male politicians, it took particular forms when directed at women. Some attacks were orchestrated to undermine the integrity of female candidates. One woman running for office told me that she found herself attacked by a group of young men while going to the market and had taken to wearing yoga pants under her dress because the men had pulled her dress up, exposing her in public. The current Minister of Lands, Public Works, Housing & Urban Development, Hon. Alice Muthoni Wahome, recounted to me the violence she faced when she ran for Kandara member of parliament with the National Alliance, which later became the Jubilee party. Her opponent unleashed a team of 50 boys to attack her. They pulled out her hair, resulting in her hospitalization for two days in the month before the election. She explained: “Three fliers were distributed spreading all manner of insults. One said I am a devil worshipper, sworn to kill 1000 women and children. Another said I was greedy with my family, and a third said that men will suckle my breasts for five years if I stand for election.” At the time, she was one of 16 women who were elected as an open constituency seat (not a reserved seat for women) in 2013, compared to 274 men.

Additionally, several politicians had to deal with opponents attempting to steal the documents certifying their nomination. Some women reported being offered bribes to withdraw from the race or were coerced into not reporting instances of harassment to the authorities. At times, hecklers were paid to disrupt women candidates’ campaigns through jeering and other disruptive tactics. Shockingly, in one instance, a deceased body was placed at the nomination site of Mary Kimwele, who was running for the position of county woman representative in Nairobi.

Today, women politicians in Kenya face the additional burden of online harassment. “Would I vie for a political seat again? Absolutely NOT!” says Helen Tullie Apiyo, who ran to be a member of the Kisumu County Assembly in 2022. “I realized that politics is a man’s world. I faced so much violence on Facebook.” She added, “I am separated from my husband, so people could say unimaginable things using [anonymous] accounts, to me and my family. It was just chaotic.”[5]

Mexico, like Kenya, is another country where hundreds of political candidates, both men and women, have been murdered or targeted. In the 2018 elections, three female political candidates were killed within 24 hours. This violence is taking place in a context where exceptionally large numbers of women are being murdered, so the political violence against women can also be seen as part of a broader pattern of misogynistic violence.[6] So far, the government has been unable to make a meaningful dent in the murders of women in Mexico: almost 3,760 women were killed last year, an average of more than ten murders every single day.[7] Today, 48.2% of the Chamber of Deputies seats are held by women, while 49.2% of the Senate seats are held by women, but the growth of extreme violence against women suggests that the targeting of women in politics is a part of this broader trend.

Conflict Zones

Political violence against women, including sexual violence, abductions/forced disappearances, violence by unidentified armed groups, and mob violence, are especially high in contexts of war, according to ACLED. The incidences are on the rise. Attempted assassinations of female politicians or repression by the state account for 47% of violence targeting women, while sexual violence accounts for 34% of all such attacks globally.[8] Some of these forms of violence take on regional characteristics: political militias targeting women are more prevalent in Africa; state forces carry out the most violence against women in the Middle East; and mobs, including those with links to political parties and religious groups, are the main perpetrators in South Asia, according to ACLED.

Potential Solutions

A wide range of measures have been adopted to deal with violence against women in politics. Some of these include raising awareness of the issue through hashtag campaigns like the aforementioned #MeTooEP. In 2018, the #MeToo movement led to the suspension or resignation of male MPs and cabinet ministers in North America, Western Europe, and beyond. Investigative reports, task forces, and surveys have raised awareness about the issue, particularly within legislative bodies. In Liberia, the National Elections Commission worked with political parties in 2005 to institute a Code of Conduct to prevent “the marginalization of women through violence, intimidation, and fraud.” Bolivia was the first country to pass a law criminalizing political violence and harassment against women in 2012. Finland has implemented various measures to tackle these issues, such as enforcing legislation against hate speech, providing law enforcement with the tools and expertise to combat online harassment effectively, and improving the capacity to identify coordinated online assaults.

Sometimes, direct engagement with perpetrators can be most effective. Former Prime Minister Julia Gillard was ruthlessly stalked for three years, denigrated by colleagues and media, and subject to a host of efforts to delegitimize her authority. The last straw came in 2012 when the opposition leader Tony Abbott accused her of misogyny, whereupon she launched into what came to be known as her iconic “misogyny speech,” in which she told the MP that “if he wants to know what misogyny looks like in modern Australia, he doesn’t need a motion in the House of Representatives, he needs a mirror.” She proceeded to detail sexist statements he had made in the House.

Finally, collective action by women politicians can also make a difference. One consequence of having a critical mass of women in a body like the Ugandan Constituent Assembly (1993-94) was that it began to change the political culture of discourse. One of the most dramatic incidents that reflected this change occurred when a male member of the assembly accused women of meaning the opposite of what they said. He launched a broadside attack on all women: “When a lady says ‘no,’ she means “yes’ and when she says ‘yes,’ she means ‘no.’” The men in the assembly broke out in laughter, but the female delegates were not amused, demanding that the chair of the assembly call the delegate to order. The delegate retorted: “A country which has no sense of humor is no worse than an atomic bomb.” Male representatives continued to laugh and stomp their feet. After several women objected, the chair finally asked the male delegate to withdraw his remark. He refused, saying, “There is a Russian saying that a frog in a pot can only see the size of the sky, which is equal to the mouth of the pot . . . Some of us [men] have lived outside the pot; therefore, we are able to see a larger part of the sky” (Ogola, CA Proceedings, 7/12/94).

At this point, one of the delegates, Miria Matembe, walked out of the assembly in protest, and all but five of the women delegates followed her. They did not return until an apology was made and the remarks retracted. As Matembe explained in her 2002 book Gender, Politics, and Constitution Making in Uganda (p. 194), “Overall, this was a victory for women. The following day, the women delegates were given a platform in the assembly to present our protest against derogatory language and insensitive attitudes toward women in the House. The issue was debated, and it was agreed that such language and behaviour were unacceptable in the House. No such incident ever occurred again in the CA.”

Conclusions

While it is clear that attacks on women in the political arena take many forms and have many driving factors, rather than attributing these diverse phenomena to a vague notion like “misogyny,” and to the idea that it derives simply from some bad actors who hate women, it is important to disaggregate the various sources and causes of the attacks. The fact that the attacks are generally being perpetrated by the very actors who are promoting women in politics suggests the need for more nuance in how we understand these forms of violence and the purposes they serve. The fact that these attacks are occurring even in countries like Finland, where women have been involved in politics for over a century and are not newcomers, suggests that it is not enough to imagine that these attacks are merely backlash to more women entering politics. The context matters, and as we have discussed in this essay, we have seen an increase in such incidents in countries amidst conflict, in countries where right-wing forces have gained ground, where violence against political men is rampant, where violence against women more generally is widespread, where dominant ruling parties are striving to maintain vote share, and where there have been increases in female representation.

[1] https://www.ipu.org/news/press-releases/2016-10/ipu-study-reveals-widespread-sexism-harassment-and-violence-against-women-mps

[2] https://www.dw.com/en/afghanistan-former-female-lawmaker-shot-dead-in-kabul/a-64398102

[3] https://yle.fi/a/3-11843330

[4] https://www.equaltimes.org/what-does-the-new-finnish?lang=en

[5] https://www.unwomen.org/en/news-stories/feature-story/2023/09/online-harassment-risks-pushing-kenyan-women-out-of-politics

[6] https://www.theguardian.com/society/2022/apr/26/murder-young-woman-mexico-femicide

[7] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/aug/09/mexico-president-amlo-gender-based-violence#:~:text=%E2%80%9CConfronting%20and%20combating%20femicides%2C%20all,10%20murders%20every%20single%20day.

[8] https://acleddata.com/acleddatanew/wpcontent/uploads/2019/05/ACLED_Report_PoliticalViolenceTargetingWomen_5.2019.pdf