Can the Constitution and Democracy Survive the Roberts Court?

The United States Constitution is and has been the cornerstone of American democracy. For more than a century, Americans have revered our governing document. But it was not always that way.

In an 1854 speech at an Anti-Slavery Society rally in Boston, abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison called the Constitution “a covenant with death and an agreement with Hell.” With these words, he lit a match to the document and, as flames engulfed the Constitution of the United States, cried, “So perish all compromises with tyranny!” Today, are we reaching another constitutional crisis because of the Roberts Court?

The Constitution changed after the Civil War; while it continues to outline and bind the promise of liberty that defines America, it now accomplishes that purpose in a way that more completely defines the roles of the states and the federal government. While Abraham Lincoln believed that the Emancipation Proclamation was “the central act of my administration and the great event of the nineteenth century,” and he stated if he were to be remembered for anything it would be the Emancipation Proclamation, but it was Lincoln’s understanding of liberty that became his greatest legacy.

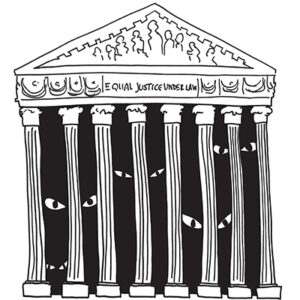

Artist: Drew Martin

Political philosophy involves an analysis of “positive” and “negative” liberty. Nearly a century before Isaiah Berlin brought that concept into political discourse in 1958, Lincoln knew all about negative and positive liberty. In 1864, near the end of the Civil War, Lincoln spoke to a group in Baltimore about differing notions of freedom. “The world has never had a good definition of the word liberty, and the American people just now are much in want of one.” As was his custom, he told a simple story, “The shepherd drives the wolf from the sheep’s throat, for which the sheep thanks the shepherd as a liberator, while the wolf denounces him for the same act as the destroyer of liberty.” Explicitly making clear to whom this new definition of liberty applied, he explained “especially as the sheep was a black one. Plainly the sheep and the wolf are not agreed upon a definition of the word liberty”.

Lincoln was thankful that “the wolf’s dictionary has been repudiated.” But actually, that repudiation is a never-ending story and is being argued over today in our Supreme Court. Lincoln professed that freedom meant aiming for equality. In his Gettysburg Address in 1863, midway through the war, he promised “a new birth of freedom” for a nation “conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” The words “all men are created equal” were only in the Declaration of Independence; if freedom were to have a new birth, the US Constitution would have to be brought into line. The decade following the war witnessed freedom for Black Americans and a redefinition of the role of the national government as a protector of freedom and liberty.

Basically, Lincoln inserted our mission statement, the Declaration of Independence, into our rule book, the US Constitution, creating a new relationship between the states and the federal government, a relationship outlined in the Reconstruction Amendments where Congress was clothed with the power to enforce the new provisions in the Constitution and the enforcement acts that followed.

At our centennials, Americans celebrated the Declaration of Independence but not the Constitution. As Supreme Court justices began to rule on the Constitution and interpret laws as to their constitutionality and in line with what the majority of the people believed to be right, our generation, especially from the midtwentieth century came to believe that the Constitution as interpreted by the Supreme Court was fundamental to our democracy.

Since the Progressive Era and World War I, most Americans have trusted our Constitution. Through most of our history there was also faith in the Supreme Court, who supposedly interpreted the Constitution, protected it and decided if any legislation or laws were unconstitutional. That process worked until recently.

The US Constitution, ratified in 1789, is the world’s oldest still in use. Norway’s constitution, implemented in 1814, is the second oldest still in use. Out of more than nine hundred constitutions written since ours, only fourteen have made it to age one hundred. For all constitutions over the period, the average predicted age at death is nineteen years. While most countries have amended their constitutions over the years or have amended their original many times, ours has been amended only twenty-seven times; since the beginning of WWI, the Constitution has been am ended eight times. The United States is unique because it has one federal constitution that governs the entire country, and each state has its own constitution. States extensively revise theirs, as they are far easier to change than the US Constitution. The US Constitution is only amendable by acts of Congress (or two-thirds of the states in a convention for the purpose) and ratification by three-fourths of the states. This system permits a balance where the states govern themselves under the US Constitution. [1]

The United States Supreme Court supposedly does not write constitutional law but interprets the document. The Court is intended to be nonpartisan, and lifetime appointees are tp ensure impartiality. Yet, the Supreme Court for the last half-century is heavily skewed toward conservatism. The court’s shocking overturning of the fifty-year-old Roe v. Wade in 2022, its granting previously unknown immunity to a president, changing federal regulations on clean air and water, and its voting decisions have eroded much of the American public’s confidence in the Court to make impartial decisions. Some see the partisan court as politicians dressed in black robes.

How can the Constitution be trusted if the Court twists and turns it to make partisan, unprecedented, life-changing decisions for the American public? Not since the Civil War era has the Supreme Court been out of step with this large a proportion of the population, and probably for the first time in American history with a majority of American citizens. Why and how did the Court get this way? Although it was once trusted as the last hope for justice, it is now perceived in low regard by many in the populace as political and partisan, and by some as corrupt and ethically compromised.

This Is Not What the Founders Intended

This is not how our founding fathers intended the Supreme Court to function. They parceled out the power of the new national government among three separate branches. Articles I and II created legislative and executive branches, and Article III created a judicial branch, headed by the Supreme Court and including such lower federal courts as Congress chose to establish. Congress first set the number of justices at six, which fluctuated in the nineteenth century to accommodate the growing number of states. It settled on nine in 1869, where it has stayed, although some tumultuous times have resulted in extreme temporary measures.

In 1788 Alexander Hamilton wrote in Federalist Paper No. 78 that the “judiciary is beyond comparison the weakest of the three departments of power” and added that it would “always be the least dangerous.” Within a few years, however, the Supreme Court asserted the authority to decide whether laws or other actions of other branches of the national government or the states were consistent with the Constitution—that is, whether such actions are “constitutional” or “unconstitutional.” No clause of the Constitution gave the Supreme Court this power. With the authority to act as the arbiter of constitutionality, the power of the judiciary has changed beyond Hamilton’s imagination, though it overturned few acts of congress in the nineteenth century. In the early twentieth century, future Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes expressed the reality: “We are under a Constitution but the Constitution is what the judges say it is.”2015 the Supreme Court had held federal laws unconstitutional 182 times and state and local law unconstitutional 1,094 times. Today the Court is viewed by many as more powerful than ever, with a partisan congressional stalemate the Supreme Court is basically assuming the legislative role and making laws.

Artist: Pedro Camargo

The overall dynamic of the court has changed over the years because people are living longer, healthier lives and justices thus retain their seats for decades longer. For the first 180 years, justices served an average of fifteen years. In the 1970s, that time inflated to an average of twenty-six years, equating to between six and seven presidential terms. A justice who is appointed around fifty—which is most of them—could serve as long as thirty-five years. As of this writing, sitting justices now range from age fifty-two (Amy Coney Barrett) to seventy-six (Clarence Thomas), with three in their seventies and two (Elena Kagan and John Roberts) in their sixties. Donald Trump’s three appointments (Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Barrett) and Joe Biden’s appointment (Ketanji Brown Jackson) are all in their fifties. As the average retirement age continues to climb, while the average age of appointment keeps dropping, justices are likely to serve even longer, leaving a substantially greater imprint on the country and the law than their predecessors did. Today’s thirty-year-old US citizen probably sees only ten new justices; sixty years ago, a person would have seen twice that many.

No other major democracy in the world today gives lifetime seats to judges who sit on constitutional courts.

The Reconstruction Amendments

The decisions of the Court have taken a meandering course since well before the Civil War. The notorious Dred Scott decision in 1857 is universally condemned for its extreme pro-slavery dogma, for twisting the Constitution to incorporate that dogma, and for thereby aggravating sectional divisions and hastening the Civil War. The Missouri lower court, however, began by recognizing that previous cases had ruled in favor of freedom for those whose masters held them in slavery in territories or states in which the institution was prohibited. Then, suddenly, the Court changed direction and abandoned precedent simply in response to antislavery sentiment elsewhere: “Times are not now as they were when the former decisions on this subject were made.” The Court thus overturned its previous cases and removed this path to freedom.

Chief Justice Roger Taney’s decision ignored evidence, especially that in at least five states, African Americans voted at the time of the US Constitution and in the slave state of North Carolina; until after the Nat Turner rebellion, free Black citizens voted on the same basis as white citizens. Taney’s ruling that African Americans could not be citizens and had no rights to be respected by whites had to be addressed in amendments to the Constitution.

The Civil War and the Reconstruction Amendments redefined personal freedom and protection in the United States. The amendments outlawed slavery (Thirteenth), equal protection of the law thus banning racial discrimination (Fourteenth), and guaranteed the right to vote (Fifteenth). All three amendments added clauses specifying that “Congress shall have the power to enforce.” Congress was thus clothed with the power to make real the rights and privileges conferred by the amendments. This alteration in the constitutional role of the states and the national government transformed a core American belief in the need to limit federal governmental power.

Congress also adopted new federal laws designed for enforcement of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments. The Enforcement Act of 1870 guaranteed the right to vote in all elections, without racial discrimination. (This only affected African American men; white and Black women alike would have to wait until 1920 before they received the same right.) The Ku Klux Act of 1871 was enacted as a result of extensive hearings about murders and outrages across the South. The expanded sections of the 1870 and 1871 legislation were intended to give the broadest protection possible. President Grant used the Ku Klux Act in a series of prosecutions that broke the back of the Klan. The Civil Rights Act of 1875 banned racial discrimination on juries, on trains and steamboats, in inns and theaters and other “places of public accommodation” and “places of public amusement.”

The Reconstruction Amendments became part of the Constitution—the fundamental law of the land—to overcome our country’s original sin. They were carefully crafted to build a wall of protections, and to ensure African Americans had a vote and a seat at the table, to be in the room where it was happening, to protect their rights. But this “second founding,” a reversal of the original federalism of the constitution was a transformation that many, including some in the judiciary and many justices on the Supreme Court, were unwilling to accept or understand. Thus followed decades in which the Court made rulings that took nearly all the power out of these amendments.[2]

The courts took out one stone at a time until the wall of protection crumbled. For example, a federal court convicted white murderers after the Colfax Massacre of 1873, but the case was overturned in March 1876 by the Supreme Court in United States v. Cruikshank. The Court found that unless the murderers were representatives of the state, such as militia or sheriffs, the federal government could not prosecute. This was a galvanizing moment for white supremacists in the former Confederacy. The Supreme Court essentially opened the door to killing African Americans.

Two particular cases marked the end of the Reconstruction Era legal protections for Black citizens. The first started when Homer Plessy decided to take a ride on a train. Though African American, seven of Plessy’s eight great-grandparents were white and he could easily pass for white. He challenged his arrest in the Louisiana Supreme Court and lost. The US Supreme Court rejected Plessy’s claims and ignored their own 1872 Brown decision, which had ruled segregated cars unconstitutional. The African American press soundly derided the decision, with one Kansas paper saying the Supreme Court had so “wantonly disgraced itself” that it was “time to put an end to the existence of this infernal, infamous body.” Some of today’s citizens echo this sentiment.

Two years later, in 1898, in Williams v. Mississippi, the Supreme Court ruled that as long as laws were race-neutral, in wording such as a poll tax, white primary, grandfather clause, literacy test, understanding clause, mass challenge laws, etc. although the effect was to disenfranchise Black citizens or exclude minorities from juries, these laws were constitutional, such as the 1890 and 1895 Mississippi and South Carolina constitutions.

That trend continued for decades, until de jure segregation finally ended for good as a result of the rediscovery of the Fourteenth Amendment in Briggs v. Elliott/Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, in the earliest days of the Earl Warren Court, and led to the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

Before Warren, however, President William Howard Taft. appointed Charles Evans Hughes. Previously the progressive Republican governor of New York, Hughes served as associate justice from 1910 until he resigned in 1916 for an unsuccessful challenge to President Woodrow Wilson’s reelection. In 1930 President Herbert Hoover return Hughes to the Court as chief justice.

Hughes, for the first time, made the Supreme Court reckon with facts and evidence in racial justice and voting cases.

He was sworn in on October 10, 1910, just in time to hear arguments for a debt peonage case, Bailey v. Alabama(1911), that would begin the Supreme Court’s long, slow turnaround on racial justice issues. Bailey was awarded a ringing victory, written by Justice Hughes, with language that was an affirmation of the Thirteenth Amendment, which for decades had been ignored by the Court. The opinion charted a new course for the Supreme Court because of one sentence: “What the state may not do directly, it may not do indirectly.”

In 1935, Chief Justice Hughes wrote another opinion that would have long-term impacts in Norris v. Alabama. He began with a crucial procedural principle: that the Supreme Court was obligated to question not only the state court’s legal rulings but also its factual findings. Without this searching examination, Hughes wrote, “review by this court would fail its purpose in safeguarding constitutional rights.”

The Court’s obligation to look at the facts for itself was a familiar one in prior Supreme Court cases on general topics, but had been ignored in the Court’s all-white jury cases. Hughes then proceeded to a withering examination of the evidence, which left no doubt that county jury officials in both Jackson and Morgan (Alabama) counties had systematically excluded African Americans for years, had lied in court to cover their misdeeds, and had even gone back and unskillfully cooked the jury books to make it look as if six African Americans had been on the jury roll, which they were not. Hughes made it clear that highly respected state leaders habitually lied.

Hughes’ opinion found for the first time in more than fifty years that African Americans had been systematically excluded from juries—and the first time in history that the Court’s decision was based on controverted evidence rather than a state’s concession. With this case and others, in twelve short years the Supreme Court had a new doctrinal framework encompassing the right to counsel, the racial makeup of juries, and oversight of state court procedural rules.

Hughes made clear that laws do not matter if they are not enforced.

The Legacy of the Modern Court

The legacy of the modern court, beginning at a stumbling walk with the Warren Burger Court (1969-1986), picking up speed in the William Rehnquist Court (1986-2005), and extending into an all-out gallop with Donald Trump’s three appointments to the John Roberts Court (2005-present), has been a steady undermining of the underpinnings of democracy, including environmental protection, gun control affirmative action and especially voting rights.

Liberal icon William Brennan, an Eisenhower appointee who had served for thirty-four years, retired in 1990. President George H.W. Bush appointed David Souter to replace him. To many people, Souter was an unknown quantity, now a rarity in these days of increasing research on any nominee. Justice Souter soon began voting with the Court’s more liberal wing. After that, great care has been taken to vet judges appointed to the Supreme Court. The Federalist Society has played a major role in that selection effort.

The organization’s stated objectives are “checking federal power, protecting individual liberty and interpreting the Constitution according to its original meaning.” The Federalist Society has become a training ground for right-wing attorneys who aspire to federal judgeships under Republican presidents and has effectively functioned to shift the country’s judiciary to the right. It vetted President Donald Trump’s list of potential U.S. Supreme Court nominees; in March 2020, forty-three out of fifty-one of Trump’s appellate court nominees were current or former members of the society. Six of the current nine Supreme Court justices (Roberts, Alito, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, Thomas, and Barrett) are or have been members.

Affirmative Action. In two landmark 2023 cases (Students for Fair Admissions v. President and Fellows of Harvard College and Students for Fair Admissions v. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill) the Court held that race-based affirmative action programs in college admissions processes violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. In these rulings, the Court ignored the core of affirmative action as it was dealt with in the Fourteenth Amendment, which was to address the historical injustices to Black people, particularly those who had been enslaved. Since some justices proclaim to be originalists or textualists, it is perplexing to understand their misreading of the clear intent of the court’s first ruling, ie the original intent of the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment from Slaughterhouse (1873) to elevate a race and protect the members of that race. Slaughterhouse explicitly explains “It is true that only the Fifteenth Amendment, in terms, mentions the negro by speaking of his color and his slavery. But it is just as true that each of the other articles was addressed to the grievances of that race, and designed to remedy them as the fifteenth.” Also, the Fourteenth Amendment was supposed to further the Thirteenth Amendment, which ended slavery everywhere in the United States and—which was interpreted and ruled by judges to end “badges of the bondsmen degradation,” still relevant today as we still see the remnants of badges of slavery.

Gun Control. In six cases since 1995, the Court has turned the Second Amendment from a protection of responsible gun use into a rallying cry for extremists and a free ticket for assault weapons. The Constitution authorizes Congress to organize and arm a militia, and the Second Amendment backs that up by providing that “a well-regulated Militia being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms shall not be impinged.” For almost all our country’s history, courts have understood that the amendment creates no personal right, only a right to bear arms in connection with state protection. As the unanimous Supreme Court said in United States v. Miller, a 1939 case involving a sawed-off shotgun, the “obvious purpose” of the Second Amendment was to ensure the effectiveness of the militia, and the Amendment “must be interpreted and applied with that end in view.”

In the late twentieth century, a new Supreme Court took a radical turn. Beginning in 1995, a 5-4 majority threw out all or parts of three modest federal laws in five years: Gun-Free School Zones Act in 1995, Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act in 1997, and Violence Against Women Act in 2000. The Court’s new tack energized gun zealots and the gun lobby. Gun extremism became a rallying cry, and if gun restraint had been difficult before, it became well-nigh impossible by the early 2000s.

In 2008, the Court took the next step. In District of Columbia v. Heller, a 5-4 majority simply rewrote the Second Amendment. These justices announced that only the words in the second half of the Amendment—“the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed”—meant anything, while the first half of the Amendment—“A well-regulated militia being necessary to the security of a free state”—all carefully crafted by James Madison and other Founding Fathers, meant nothing at all. The irony that the whole point of the militia clause was to protect state rights, which the Supreme Court overrode. Five justices said the first half of the Second Amendment was simply a “prologue,” and “prologues,” they said, do not count! They repeated the word “prologue” ten times. Thus, the first dozen words of the Second Amendment just disappeared. Its guiding principle—“the security of a free State”—also disappeared from the Supreme Court’s view.

These cases all dealt with federal law. But these justices, who say they favor states’ rights, soon applied their new-found constitutional theory to dismantle widely popular state gun laws. In 2010, in McDonald v. Chicago, the Supreme Court began throwing out gun laws passed by the states; in 2022 in New York Rifle Association v. Bruen, the majority threw out a New York state law that had been on the books for nearly 150 years. The dissenting opinion in the New York case cited gun violence statistics, but Justice Alito complained that statistics were not relevant. Once again the Court ignored the importance of evidence and facts (including amicus briefs by expert historians). Yet, statistics about rising gun violence show that the Second Amendment’s purpose—“the security of a free state”—is getting farther and farther away. A dozen states and hundreds of counties, calling themselves “Second Amendment Sanctuaries,” have now resolved not to endorse any gun laws.

The Supreme Court’s thirty-year string of ruling for guns and its invention of false doctrine—the “prologue” theory—has endangered the security of a free state—just the opposite of the Second Amendment’s command. The Supreme Court has helped normalize the use and misuse of guns, bringing high-powered weapons from movie screens to our streets and schools, and every public and private place where security, not danger, should abide.

Separation of Church and State. Faith used to be the story of how God helps us be better people, but in the Supreme Court’s hands, it has become a tool for mistreating other people. The Hobby Lobby Corporation, a nationwide chain of more than five hundred stores, complained that it should have the religious freedom to reject contraceptive services in its employee health plan. The Supreme Court loved the theory that the company could ride on the religious coattails of its owners and deny contraceptives to its 13,000 employees. The owners’ religious beliefs, however, did not stop them from being involved in a huge scheme to steal artifacts and smuggle them into the country, culminating in a multi-million dollar fine.

Thus the Roberts Court originalists, textualists, and conservatives elect to read the First and Second amendments as broadly as they can but inconsistently read the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth amendments as narrowly as they can.

Environmental Protection. The Supreme Court has made several recent rulings that have limited the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) authority to regulate the environment. In an upcoming case the Court will revisit a doctrine about Congress’s ability to hand off power to executive agencies. These past and future cases mean a huge shift in federal environmental policy. The case came to the Court through its emergency appeals (also known as its “shadow”) docket. It stems from how the EPA interprets a provision of the Clean Air Act known as the “good neighbor” provision, which requires states “upwind” to reduce emissions that affect air quality downwind. Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote the opinion, saying the plan’s emissions standards could cause harm to half the states. He was joined by Chief Justice Roberts and justices Thomas, Alito, and Kavanaugh.

Other recent decisions concerned carbon monoxide emissions in 2022, in which the Court limited the EPA’s ability to regulate carbon dioxide emissions from power plants that contribute to global warming, and further weakened the Clean Water Act by limiting the EPA’s oversight of wetlands. In Sackett v. EPA, the court ruled that the CWA’s use of the word “waters” refers to “streams, oceans, rivers, and lakes” and adjacent wetlands that are “indistinguishable” from those bodies of water.

John Roberts’ Handprints on Trump Decisions

In a New York Times investigation published on September 15, 2024, Jodi Kantor and Adam Liptak reported on behind-the-scenes emails and maneuvers by which Chief Justice Roberts took control over key decisions and ultimately controlled the outcomes of three cases related to January 6, 2021. The most consequential of the three declared Donald Trump immune to prosecution for past actions. Roberts wrote the opinions on all three, including an unsigned one in March 2024 that decided in favor of Trump remaining on the ballot in Colorado. Another case involved a switch in which the case (concerning whether prosecutors had gone too far in bringing obstruction charges against some Capitol rioters) was originally assigned to Justice Samuel A. Alito, but Roberts took it over and, as in the pre-Charles Evans Hughes days, ignored evidence including amicus briefs by expert historians who studied these issues and also ignored precedent to change the rule of law and a core American belief that had been part of the United States since its beginning that no one was above the rule of law.

The Vital Importance of the Senate and the Bench

Powermongers use the US Senate to stack the benches of the courts. If Republicans take the Senate, they can not only block all popular Democratic legislation, as they did with gun reform after the Sandy Hook massacre, but they can also continue to control the judicial system. As long as conservatives have a majority of judges in place to make law from the bench, it does not matter what the majority of Americans want.

This slithering around behind the scenes has been going on since the Reagan administration. In 1986, when it was clear that most Americans did not support the policies put in place by the Reagan Republicans, the Reagan appointees at the Justice Department broke tradition to ensure that candidates for judgeships shared their partisanship. Their goal was to keep the tenets of the Reagan revolution going so it could not be set aside, whatever the outcome of future presidential elections.

That principle continued when Mitch McConnell became Senate minority leader in 2007. Federal judgeships depend on Senate confirmation, and McConnell worked to make sure Democrats could not put their own appointees onto the bench. He held up so many Obama nominees that Democratic Senate majority leader Harry Reid began prohibiting filibusters on selected nominees. McConnell, however, weaponized the filibuster so that nothing could become law without sixty votes in the Senate.

McConnell became Senate majority leader in 2015, and his power increased. McConnell refused even to hold hearings for Obama nominee Merrick Garland when Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia died in February 2016, saying that the nomination was too close to an election, even though it was nine months away, and the new president should make that nomination. Trump won in 2016, and Republicans got control of the Senate. In 2017, McConnell killed the filibuster for Supreme Court nominees when Democrats tried to filibuster Trump’s nomination of Neil Gorsuch, and Brett Kavanaugh was confirmed with fifty votes and Amy Coney Barrett with fifty-two. At the time Barrett was confirmed, it was in late October 2020 and voting for the next president—who turned out to be Joe Biden—was already under way. The ploy—which shows McConnell’s blatant hypocrisy in the face of his decision four years before—worked, because those justices’ votes were critical in successfully and comfortably overturning Roe v. Wade in 2022, which Donald Trump had long maintained was a major goal. He openly and aggressively stacked the court with judges to overturn Roe.

Roe V Wade. Some justices, led by Justice Alito, had been longing to overturn Roe for years. The decision to overturn rested largely on the definition of “liberty” in the Constitution. To come up with the Court’s definition, Alito relied on Sir Matthew Hale, a seventeenth-century English judge noted for trying and hanging women for witchcraft. “Liberty” for women under our Constitution did not really begin until a series of early 1970s Supreme Court cases. Before then, it was perfectly constitutional for federal and state governments to discriminate openly against women, but post-1970 cases across all fronts—from marital status and inheritance laws to education and even alcohol consumption—recognized new dimensions of liberty for women. Therefore, when Roe v. Wade was decided in 1973 and repeatedly reaffirmed, “liberty” had a new constitutional meaning. Rejecting that in favor of a witchcraft-era definition of “liberty” was a gross misreading of the Constitution. The court again ignored evidentiary based amicus briefs by expert historians.

The Voting Rights Act. Democracy has always been about the vote, The federal right to vote, created in the mid-nineteenth century, and continued in the 1950s and 1960s was a structure formed of both constitutional and statutory protections for both voters in general and minority voters in particular. Decisions of the Roberts Court since 2005 have taken aim at every part of that structure.

The 1965 Voting Rights Act the most successful civil rights law in American history—has been central in ending Jim Crow voting and had overwhelming bipartisan support in Congress. The most-used section of the Act was Section 5—the preclearance mechanism. Preclearance blocked a thousand large and small voting changes by the early 2000s, each one the equivalent of a successful lawsuit. It applied only in the states with the worst record of voting discrimination, and provided that any new voting law or rule in those states was blocked unless it was proven to be nondiscriminatory.

John Roberts had been gunning for the Act long before he joined the Supreme Court. As a special assistant to William French Smith, the attorney general in the Reagan administration, Roberts wrote memoranda opposing key parts of the VRA, especially Section 2. He was also skeptical of Section 5, in spite of a huge amount of testimony and evidence presented to Congress that showed the continuing need for Section 5 coverage in the South. When the Act came before the Court, Roberts invented a doctrine called “equal sovereignty” that is not in the Constitution but was pieced together using bits of other rulings. Such a doctrine had been argued in the original Voting Rights Act case, South Carolina v. Katzenbach (1966), but had been explicitly rejected by the Warren Court. Now, in a ruling on Northwest Austin Municipal Utility District v. Holder (2011), Chief Justice Roberts’s opinion resurrected the doctrine and quoted selected words from the Katzenbach opinion that made the earlier case seem as though it supported the “equal sovereignty” doctrine, but omitted twenty-two crucial words that showed South Carolina v. Katzenbach held exactly the opposite. Printed here on the left is the paragraph as it appeared in South Carolina v. Katzenbach, and on the right as it was rendered in Northwest Austin:[3]

|

Katzenbach |

Northwest Austin |

| “The doctrine of the equality of States,

invoked by South Carolina, does not bar this approach, for that doctrine applies only to the terms upon which States are admitted to the Union, and not to the remedies for local evils which have subsequently appeared.” |

“The doctrine of the equality of States, . . . ,

does not bar . . .

remedies for local evils which have subsequently appeared.” |

Four years later in 2013 Shelby County, Alabama v. Holder, Shelby County cited Northwest Austin more than twenty times, repeatedly wielding the words “equal sovereignty” with a vengeance. The grievous misquotation from South Carolina v. Katzenbach was not repeated, but its damaging work had been done. A 5-4 opinion by Chief Justice Roberts treated “equal sovereignty” as a settled constitutional principle, supported by no authority other than Northwest Austin with its misbegotten heritage. As a coup de gras, the linchpin of the majority opinion was that “40-year-old facts” about voter discrimination have “no logical relation to the present day,” which echoes Dred Scott.[1]

In dissent, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg had a pithy rejoinder to the majority’s notion that voting problems were all but wrapped up: “Throwing out preclearance when it has worked and is continuing to work to stop discriminatory changes is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.”

Roberts explained gutting Section 5 by echoing the lower court in Dred Scott that things were not what they were in 1965 and argued that there were still Section 2 claims. But Judge Alito had his eye on Section 2 as well. Again echoing the words of the lower court judge in Dred Scott and Roberts in Shelby County, Alito said “things are not as they were in 1982” when the VRA was renewed and expanded. Ironically, Alito was right. What states are doing today is worse than what they did in 1982.1982, twenty-two years after passage of the VRA, states had accepted the right of minorities to participate in elections and the states’ efforts were how to dilute the impact of minority citizens’ vote. But today is much more like 1898 and Williams v. Mississippi, as states try not only to dilute the impact of minority voters but also to keep them from voting by crafting neutral-sounding laws that effectively disenfranchise one group of people. Especially important now are incomplete or some minor mistake by a voter, particularly in absentee voting or using dropboxes. The courts have used the precedent of the intent of the voter since Bush v Gore in 2000 and hanging chads till the Roberts Court’s partisan rulings, including allowing mass challenges of registered voters and making it more difficult for minorities to register and to vote..

Section 2 remains on the books, but the provision emerges in a severely weakened state, and is not out of danger. Over the last ten years, the Roberts Court has taken a newly renewed VRA that was on the march and left it an anemic tool whose future is uncertain.

Corporate Campaign Funding

Although not explicitly about voting rights laws, a 2010 case has arguably had more impact on the influence of voting. The Supreme Court handed down Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission decision, declaring that corporations and other outside groups could spend as much money as they wanted on elections, calling it a function of their freedom of speech. Moreover, they could be anonymous, making dark money available. Corporate political contributions had been a federal crime for a hundred years, since the Tillman Act of 1907, which was the first campaign finance law in the United States. the Tillman Act stood firm while Chief Justice Rehnquist and Justice Sandra Day-O’Connor were on the Court.. Since they were replaced by justices Roberts and Alito, the Court has never affirmed a campaign finance restriction. Citizens United allowed corporations and billionaires to financially support candidates for seats in legislative bodies, and in the 2010 midterm elections. Republicans won majority legislatures in time to be in charge of redistricting their states after the 2010 census. Republicans controlled the key states of Florida, Wisconsin, North Carolina, Ohio, and Michigan, as well as other, smaller states, and used precise computer models to win previously Democratic House seats after the election.

Lobbyist groups, such as the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), are in the business of getting those dollars and legislative wins for their clients. ALEC’s website claims it is “America’s largest nonpartisan, voluntary membership organization of state legislators dedicated to the principles of limited government, free markets and federalism.”[1] Its critics say it is a group of corporate lobbyists who meet behind closed doors and push dangerous, far-right legislation. As CommonCause.org explains, “ALEC creates ‘model bills’ that undermine our rights, then has state lawmakers introduce them almost word-for-word as real legislation that often becomes law, weakening our democracy and enriching ALEC’s corporate donors at our expense.”

Money talks. In 2012, Democrats won the White House decisively, the Senate easily, and a majority of 1.4 million votes for House candidates. Yet Republicans came away with a thirty-three-seat majority in the House of Representatives.

A parade of new procedures, laws and rules followed, each seemingly unrelated but together depicting a Court that disparages voters and values financial contributors. Examples are voter suppression laws, such as in-person photo ID laws, and other laws that seem designed specifically to disenfranchise minority voters in urban areas that vote Democratic.

In 2019 the Court ruled that “partisan gerrymandering claims present political questions beyond the reach of the federal courts” , in Rucho v. Common Cause. Roberts delivered the majority opinion and made clear that political gerrymandering can be distasteful and unjust, but that states and Congress have the ability to pass laws to curb excessive partisan gerrymandering. Justice Elena Kagan’s dissenting opinion criticized the majority. “Of all times to abandon the Court’s duty to declare the law, this was not the one. The practices challenged in these cases imperil our system of government. Part of the Court’s role in that system is to defend its foundations. None is more important than free and fair elections. With respect but deep sadness, I dissent.”

The country is still experiencing a deluge of new state laws rolling back voter access. In a slew of other cases, the Court has eviscerated other key protections in federal law and made it harder for Americans to get relief from discrimination, gerrymandering, and burdens on their freedom to vote. In the first decade after Shelby County, at least twenty-nine states had passed ninety-four restrictive laws to manipulate election processes and subvert election outcomes. They have pursued partisan efforts to disempower other elected offices and sought to undermine the ability of the people to exercise their power through direct democracy. And, as in North Carolina and Texas, they have drawn extreme partisan gerrymanders that prevent fair representation.

The Electoral College

In a country of fifty states and Washington, DC— more than 330 million people—presidential elections are decided in just a handful of states, and it is possible, even likely, for someone who loses the popular vote to become president. We got to this place thanks to the Electoral College, and to two major changes made to it since the ratification of the Constitution.[4]

Each state has a number of electors that is the total of two senators and however many representatives it has in Congress. A small state has at least three electors. A large state has fewer than its share, as the representatives cover much more populated areas. Thus, gerrymandering and redistricting are essential in shaping who can be electors and, thus, who can be president. The president appoints all Supreme Court justices and federal court justices for life. The United States is not a parliamentary form of government; the presidency is a winner-take-all election, and the consequences are extraordinary on our Court system and hence on our constitutional laws since the president makes those appointments and other regulatory appointments as well as a number of other federal appointments that directly affect elections and the lives of all citizens.

The drama began in 1796. John Adams won, but Thomas Jefferson saw that if he had won all of Virginia’s electoral votes, rather than a portion of them, he would have won. He persuaded his native Virginia to switch the system, and in 1800 he received all of Virginia’s electoral votes. Massachusetts, which favored native son Adams, then switched their system to winner-take-all so Adams could get their votes.1836, every state except South Carolina (where state legislators chose electors until 1860) had switched to winner-take-all.

James Madison, “Father of the Constitution,” was horrified by the early changes. He wrote in 1823 that voting by district, rather than winner-take-all, “was mostly, if not exclusively in view when the Constitution was framed and adopted.” He proposed a constitutional amendment to end winner-take-all. Today, only Maine and Nebraska use congressional district methods rather than winner-take-all. They allocate one vote per congressional district and award the final two votes to the state winner.

In 1824 the Electoral College split the votes among four candidates, and no one had the majority. The House of Representatives gave the election to John Quincy Adams instead of the highest popular vote, Andrew Jackson. Jackson won the next election, and he asked for a constitutional amendment to elect the president by a popular vote instead of Electoral College votes. The North was outgrowing the South in population, and the South had an advantage in the Electoral College because enslaved persons who had no vote were counted as three-fifths of a person for purposes of the census, which was all-important in determining Congressional representation and, thus, the number of Electoral College votes.

In our history, four presidents—all Republicans—have lost the popular vote and won the White House through the Electoral College. These were Rutherford B. Hayes in 1876, Benjamin Harrison in 1888, (and in 1876 and 1888 most Black men were prevented from voting or did not have their vote counted in the South), George W. Bush in 2000, and Donald Trump in 2016. Trump’s 2024 campaign strategy appears to be able to do it again, or to create such chaos that the election goes to the House of Representatives, where there will likely be more gerrymandered Republican-dominated delegations than Democratic ones.

A new wrinkle in 2024 makes that single vote even more important. The Constitution’s framers agreed on a census every ten years so that representation in Congress could be reapportioned according to demographic changes. As usual, the 2020 census shifted representation, and so the pathway to 270 electoral votes shifted slightly. Those shifts mean that it is possible the 2024 election will come down to one electoral vote. Awarding Trump the one electoral vote Nebraska is expected to deliver to Harris could be enough to keep her from becoming president.

Senator Lindsey Graham (R-SC), who had been reported as trying to influence the decision in Georgia after it went for Democrat Joe Biden in 2020, went to Nebraska in 2024 in an eleventh-hour desperation attempt to try and convince the Republican-dominated legislature to change the Republican-heavy state to change to a winner-take-all method, hence denying the Democrats a critical vote.

If no one reaches 270 votes, the election would be decided by the House of Representatives, where careful planning and gerrymandering would likely deliver the election to Trump. And if not, Trump will almost certainly fight the election outcome and will go to any lengths necessary to win, as he proved in 2020. On December 3, 2020, he posted on Truth Social: “A Massive Fraud of this type and magnitude allows for the termination of all rules, regulations and articles, even those found in the Constitution. Our great Founders did not want, and would not condone, False and Fraudulent Elections!” He later said his words were twisted but did not delete the post.

How Do We Get Out of This Mess?

Benjamin Franklin was in the last day of the Constitutional Convention in 1787. At eighty-one, he was weary of the fight for signatures on the Constitution. Almost everyone signed, and the document’s fate was then in the hands of the states to ratify. According to notes in the journal of Maryland delegate James McHenry, Elizabeth Willing Powel of Philadelphia asked Franklin, “Well, Doctor, what have we got, a republic or a monarchy?” Franklin replied, “A republic, if you can keep it.’” The question remains an issue with which we continually have to grapple, as the Constitution is a living, breathing thing for whose principles we have to fight.

The Enormous Impact of Unexpected Change

History is contingent and we cannot predict change. The Court’s history is honeycombed with small changes and contingent moments that have made large differences, and which give us hope for other unexpected changes,

That history goes back to the earliest days of our Republic. In 1800, Thomas Jefferson’s Republican Party won a clean sweep of the White House and both houses of Congress. It was the end of the Federalists as a national party—except at the Supreme Court, where lame duck officials achieved a different outcome. After the election, Chief Justice Oliver Ellsworth resigned, and already-defeated President John Adams nominated John Marshall, a strong Nationalist, to be chief justice. The lame duck Senate confirmed the nomination. All of this took place after Jefferson was elected but before he was sworn in. Marshall went on to dominate the Supreme Court for thirty-five years while Jefferson and four more presidents watched in fuming frustration.

The Court had several brushes with unexpected change and contingency during the Great Depression of the 1930s. A reactionary 5-4 majority of the Court repeatedly blocked New Deal efforts to combat the country’s economic disaster, prompting President Roosevelt to propose a plan to create additional Supreme Court seats that he could fill. Amid the uproar over this plan, Justice Owen Roberts, one of the five justices who had consistently voted to strike down the New Deal measures, shocked the nation by suddenly reversing his position and voting to uphold all the New Deal measures. This single change, which ended the Court’s greatest constitutional crisis, has been called “The Switch in Time that Saved Nine.”

In 1953, with the Briggs v. Elliott et al. segregation cases at the Supreme Court, the Chief Justice was Fred Vinson, one of four justices from the South or border states. Vinson believed in fairness but was widely seen as not ready to end segregation and certainly not about to lead the Court to that result. In September 1953, just four weeks before the school segregation cases were scheduled for argument, Vinson died of a sudden heart attack at age sixty-three. President Dwight Eisenhower’s choice to replace Vinson was Earl Warren, who led the Court to a unanimous decision ending segregation (Briggs v. Elliott/Brown v. Board of Education) and went on to a storied tenure as chief justice. One of the other justices, when he heard of Vinson’s sudden death, said, “This is the first proof I have ever had of the existence of God.”

The end of the Warren Court was almost as sudden as its beginning. In 1968, the Warren-led Court was the most liberal in history. As Warren got ready to retire, President Lyndon Johnson nominated Associate Justice Abe Fortas, another strong liberal, to become chief justice and chose another liberal, a lower court judge, to take Fortas’s seat. When Johnson tried to elevate him, however, the nomination faced a filibuster and was withdrawn. Fortas later resigned from the Court after a controversy about accepting $20,000 from a financier who was being investigated for insider trading (which pales when compared to the blatant conflicts of interest of Roberts, Alito, and Thomas). Richard Nixon was elected president, and he chose conservative Warren Burger as chief justice. Fortas returned to private practice, and suddenly the most liberal Court in history was gone.

The Court grew ever more conservative, and the conservative trend has now been almost unbroken for more than a half-century, during which there was one moment when the direction might have been stopped or reversed—with a single change.

That moment was the 1991 retirement of Justice Thurgood Marshall. For years he said he had a lifetime appointment and expected to serve out his term, often joking, “I expect to die at the age of a hundred and ten, shot by a jealous husband.” But his health deteriorated and, with everyone expecting President George H.W. Bush to be reelected handily in 1992, Marshall retired in 1991 and was replaced by Clarence Thomas. Bush lost to Bill Clinton, and Marshall lived to see Clinton’s inauguration. If Marshall had been able to endure or ignore his health issues and stayed on the Court, his successor would have been a Clinton appointee.

Speculating about history is always hazardous but think of the possible domino effect if a Clinton appointee succeeded Marshall. A different 5-4 majority, with a Clinton justice instead of Justice Thomas, might have rejected George W. Bush’s request to overrule the Florida courts in the Supreme Court’s 2000 case of Bush v. Gore. That might have changed who was sworn in as president in 2001. Would we have gone to war in Iraq in 2003? And who would have been elected president in 2004, in a position to name the replacements for Chief Justice Rehnquist and Justice O’Connor, who both left in 2005? Their replacements, Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Alito, remain on the Supreme Court today. In the years after those 2005 appointments, the Court has rendered momentous decisions on gun rights, campaign spending, reproductive freedom, the Voting Rights Act, and affirmative action—all by 5-4 votes. All of this is speculation, of course, but it shows how huge consequences can flow from a single small change and contingent moments.

Since Donald Trump appointed Justice Barret, 6-3 decisions are common, with justices appointed by a Republican president voting one way and justices appointed by Democratic presidents voting another. More and more citizens believe the Court is becoming just another political branch—it is not making rulings according to the law or precedence or evidence; it is making them because of politics. President Biden is now making calls for changes in term limits and ethics, which might focus people’s attention on the court itself and how change could be made. Do not bet against change.

The Importance of Evidence

We all need to reckon with the history and the historical evidence. Henry Adams, son of Charles Francis Adams who was ambassador to England during the Civil War proclaimed in The Education of Henry Adams that the American mind “stood alone in history for the ignorance of its past.” His great grandfather, our second president, who also stood alone among the early presidents, along with his son John Quincy Adams as an opponent of enslavement. They are the only two of the first twelve US presidents who did not own enslaved people at some point in their lives. John Adams said, “Facts are stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passions, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence.” As Charles Evans Hughes demonstrated courts must have fact based evidence for fair and just decisions. We must continue to construct a record for evidence, if for no other reason than to build a record of dissent. Historians today celebrate dissenters who called for the honesty and the evidence. the very evidence that would have led to a different ruling in Dred Scott or Plessy v Ferguson or Williams v. Mississippi, and all of the laws that ruled against equal justice under the law. Those are the people that historians now study and hold up as the heroes, the people who tried to do the decent, honest, and right thing. It will not be Chief Justice Roberts or Justice Alito, or Justice Thomas but it will be the great modern dissenters—Justices Sonia Sotomayor, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Elena Kagan, Ketanji Jackson—who will be celebrated as those who are trying to save the basis of our democracy.

Faith Based Justice. “Hate evil and love good, and establish justice in the gate” Amos 5:15a

Some Justices serve as examples of how their faith influenced them to support justice. John Marshall Harlan, a Kentucky native who served on the Court from 1877 until his death in 1911, is often called “The Great Dissenter” because of his dissents in civil liberties cases. He was not afraid to be alone in his dissents, as evidenced in the Civil Rights cases (1883) and Plessy (1896). He grew up in a family who owned enslaved people; he opposed the Emancipation Proclamation but fought for the Union. Harlan was largely forgotten in the decades after his death, but many scholars now consider him to be one of the greatest Supreme Court justices of his era. Some of his views would become the Court’s official view beginning with the Warren Court. Harlan was a devout Presbyterian elder who taught Sunday school, and his faith influenced his decisions, even though a white supremist he championed equal rights for Black people under a color blind constitution. Charles Evans Hughes was a corporation lawyer but took the American Baptist faith of his missionary immigrant father and practiced it deeply, which led him to read the law fairly and justly. When the Court moved into its new building in 1935, a guard rejected African Americans who had tried to enter the restaurant. The progressive historian Woodrow Wilson had segregated the federal government, so Black people were not allowed. Hughes took the guard outside and asked him to read the words over the entrance to the new Supreme Court building: “equal justice under the law.” Hughes told the guard that if he could not uphold that, he should get another job. After that, the restaurant in the Supreme Court building was open to all people. Several justices, including some appointed by Donald Trump, claim to be devout in their faith. We would never question anyone’s faith and we have hope that their faith will lead them to consider Amos’ pleading in the impactful decisions they make. We believe faith is powerful and have seen in history where it makes a difference. It is our hope that as justices study the evidence, like Harlan and Hughes did, their faith will make a difference as they try to follow the evidence in the rule of law.

Yesterday and Today

The precarious moment in which we find ourselves is reminiscent of the difficult choices and perils the Civil War and Reconstruction generations faced such as the 1836 gag order in Congress that John C. Calhoun engineered to silence discussions regarding slavery and also of the rise of authoritarian leaders who opposed Reconstruction. Today there is political backlash comparable to the counterrevolution after Reconstruction.

We recognize similarities between the Civil War era and our own. The Confederacy was much more in line with the rest of the world than was the United States. The world was moving away from democracy toward authoritarian and monarchy regimes. Citizens’ ability to govern themselves were questioned and republics like France and Mexico became monarchies again. Lincoln meant it when he said the United States was the “last best hope” for democracy, where meritocracy, as imperfect as it was could still have an opportunity to work. We too must be willing to fight to preserve that last best hope, as did Lincoln. How might this be done? Is it a mistake to bring up the unpleasantness of past discrimination with fact based evidence I a time of Donald Trump’s alternative fact universe? Should we ignore rather than dwell upon past lynching, segregation, and indignities? Does it not just rile emotions? Is it better to “get over it” and move on? Robert Penn Warren warned, “if you could accept the past you might hope for the future, for only out of the past can you make the future.” Minimizing historical atrocities, sweeping “unpleasantries” under the rug, only creates issues we keep tripping over.

It is not accidental that the Civil Rights Movement is called the Second Reconstruction. Today we are still stumbling over issues of Reconstruction—citizenship and the Fourteenth Amendment, refugees, immigration, racist campaign rhetoric, violence, women’s rights, who can use guns and for what purposes, terrorism, poll taxes and vote restriction laws, law enforcement and policing, incarceration, demagoguery, scapegoating, Nativism, and the rise of authoritarianism. In that regard, the first and second Reconstructions are still playing out in American history, and we need to give the public alternative role models beyond the heroes with feet of clay who are now in office and on the bench.

As Martin Luther King Jr. challenged us in his Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech, “I refuse to accept the idea that the “‘isness’ of man’s present makes him morally incapable of reaching up for the eternal ‘oughtness’ that forever confronts him.” In a 1988 speech at the Democratic National Convention, South Carolinian and King disciple Jesse Jackson called on us to “keep hope alive. It may look grim, but we must keep on keeping on. Onward!” Abraham Lincoln wrote in a speech in the US House of Representatives in 1848: “Determine that the thing can and shall be done, and then we shall find the way.”

We take inspiration from the young people who will be writing the next chapter. In 2019–2020 Amanda Gorman (who was then the US Youth Poet Laureate), gave readings around the country of a poem she had been commissioned to write for Independence Day. Echoing Lincoln’s two greatest speeches The Gettysburg Address and his second inaugural where he spoke of our “unfinished work,” in her performance at the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Gorman, an African American woman from Los Angeles who was then a student at Harvard, explained that she sees American democracy not as “something that’s broken,” but as “something that’s unfinished.” Rather than falling prey to discouragement, she speaks of being “audacious” in “taking up the mantle” of our founders and playing her role in finishing their work. In her poem “Believers’ Hymn for the Republic,” she declares, “Every day we write the future together.” We have faith in the young people of America who believe in liberty, freedom, democracy, fairness, and equality. It is a lot to ask, but young people with their better values and fewer prejudices can hopefully save us from the Roberts Court. Often attributed to Abraham Lincoln, who probably said something similar, actually it was Justice Robert H. Jackson who understood and explained in 1949 that “the Constitution is not a suicide pact”; and now we today cannot allow the Supreme Court to destroy American democracy.

*The authors appreciate the help of research assistant Matthew Girardeau.

[1] . Two of these—New Zealand and Canada—are anomalous cases of former British colonies in which the “constitution” consists of multiple documents and might be seen as distinct species. Great Britain itself still functions without a concisely written constitution. Of the 27amendments to our constitution, there have been no substantial amendments since 1971; in 110 years the constitution has only been amended 8 times in 110 years, including two amendments, 18 and 21 that cancelled each other, Leaving aside the Bill of Rights, our constitution has been. Amended 17 times in 235 years.

[2] For details on the amendments, enactments, and the undermining see Orville Vernon Burton, The Creation and Destruction of the Fourteenth Amendment During the Long Civil War,” Louisiana Law Review, Vol. 79 (Fall 2018): 189-239 and “Tempering Society’s Looking Glass: Correcting Misconceptions About the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and Securing American Democracy” Louisiana Law Review Vol. 76:1 (2015): 1-42.

[3] This critical omission of words by Roberts was first pointed out in Orville Vernon Burton and Armand Derfner, Justice Deferred: Race and the Supreme Court, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2021; and elaborated on in Armand Derfner, “Can Our Democracy Survive This Supreme Court?” University of Chicago Press, The Supreme Court Review, Vol. 2023, issue 1, pp. 345-395.

[4] For a more detailed history of the electoral college see Heather Cox Richardson, Letters from an American, September 20, 2024.