Triumph of the Vanguard

Not often is an author forced to reevaluate the conclusions of his own book days after its final submission, yet that is exactly what happened to me in the winter of 2021.

My book, Far-Right Vanguard: The Radical Roots of Modern Conservatism, came out in October of that year, but I had completed the writing nearly a year beforehand. I turned in the final copy to my editor, the brilliant Bob Lockhart, on January 4, 2021. As a first time author, hitting send on that email was both exhilarating and exhausting. The project I had worked on for years was now out of my hands.

Two days later was January 6, the planned date of a “big protest” that Donald Trump had promised his Twitter followers would “be wild!” I remember glancing at my phone, seeing the images flooding Twitter, and sprinting up the stairs to grab my wife, “There’s a mob storming the Capitol!” We spent the next few hours glued to the television, watching an attempted coup unfold before our eyes. Harrowing images and videos emerged in the following hours and days. An erected gallows. Chants of “Hang Mike Pence” puncturing the winter air. Crowds bludgeoning police officers with ad-hoc weaponry. The presence of numerous right-wing paramilitary organizations. It was, without a doubt, one of America’s darkest moments since the Civil War.

Even with all of this happening, or perhaps especially because all of this was happening, I kept thinking about the last line of my book: “Whether or not America’s illiberal turn is an ephemeral shock or a sign of dark times ahead, one thing is certain: the mid-century far right laid the foundation for the acerbic conservatism coursing throughout the country today.” When I wrote those words, it felt right to leave the book on a bit of a cliffhanger. America, perched at a fork in the road.

In the years since January 6, the dark times feel close enough to touch. Democracy appears even more imperiled. The Republican Party has been fully subsumed by Donald Trump’s cult of personality. Trump acolytes and allies line the halls of Congress, broadcast on news stations and podcasts, and control powerful social media networks. Despite the efforts of establishment Republicans to maintain a grip on the party, Trump’s particular brand of populist authoritarianism still energizes the conservative base. At this point, even if Trump loses in 2024, the illiberal fever on the right shows no signs of breaking.

* * *

In the years since Far-Right Vanguard came out, the literature on the far right has exploded. Scholars have repeatedly found that the radicalism bubbling up in our modern era stems from a deep historical reservoir. As historian Steven Hahn recently wrote, “[O]ur present-day reckoning with the rise of a militant and illiberal set of movements has lengthy and constantly ramifying roots.” Trump is not an aberration, but a culmination.

The United States was built upon an edifice of minoritarian rule, and many of those illiberal structures persist. The Electoral College and intense gerrymandering, especially in GOP-led states, ensure that Republican politicians have a built-in electoral advantage. The Senate’s equal representation means less populated, rural states have equal, if not more, power than larger, more populated states. The Supreme Court remains essentially untouchable–no justice has ever been removed from office–even in the face of open corruption. The infamous Citizens United case allowed a deluge of money to flood American elections, putting a giant money bag on the electoral scale in favor of the wealthy and powerful. And, to add insult to injury, the Supreme Court gutted key portions of the 1965 Votings Rights Act, which has allowed individual states to further restrict access to the ballot.

Taking advantage of these illiberal structures, conservatives are attempting to set up a nationwide electoral apartheid. Numerous GOP-led states, especially in the South, have implemented a variety of policies to suppress voting rights. It’s a very Calhounian idea – preserve the status quo by keeping the wrong people from accessing the levers of power. When conservatives shout, “We’re a republic, not a democracy,” this is the logical conclusion: they believe some votes should just count more than others. In effect, conservatives are trying to stretch the illiberal authoritarianism of the Jim Crow South across the entire nation.

Trump has eagerly exploited America’s illiberal governing structures. Even before the mob stormed the Capitol on January 6, Trump’s team executed multiple strategies to subvert democracy. His campaign filed numerous lawsuits alleging, in various ways, that the election had been stolen. There were claims of faulty voting machines, fraudulent votes, and outright bribery. Dozens of lawsuits, in all. These cases were each shot down, in one court after another. On January 2, Trump telephoned Brad Raffensperger, who was then serving as Georgia’s Secretary of State. He pressured Raffensperger to “find 11,780 votes,” hoping to tip the Peach State into Trump’s electoral column. Trump would later describe this phone call, a brazen attempt at electoral interference, as “perfect.” As the electoral vote count neared, attorney John Eastman, the former director of the far-right Claremont Institute’s Center for Constitutional Jurisprudence, developed a scheme to replace Joe Biden electors with fabricated slates of Trump electors. Mike Pence, to his credit, refused to go along with the plan and instead rightfully certified the election in Biden’s favor.

For a brief, shining moment in the days after January 6, it looked like the Republican Party might do the right thing. A tangible bipartisan urgency to impeach and remove Donald Trump from office coalesced. The House of Representatives voted in favor of impeachment, 222-197, with ten Republicans joining their Democratic colleagues. The Senate, however, failed to reach the supermajority required to remove Trump from office, yet another example of minoritarian rule preventing justice from being served. A handful of Republican Senators voted in favor of removal, making themselves targets for Trump’s ire. Mitch McConnell, the Republican stalwart and Senate Minority Leader, had only days earlier blamed Trump for the January 6 riot. He voted against removal anyway.

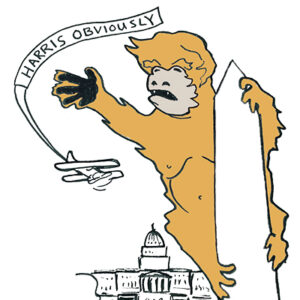

Artist: Drew Martin

The whole episode was a travesty of leadership and a remarkable revelation of cowardice within Republican ranks. If parties are the gatekeepers of political normalcy, GOP leaders abandoned their post years ago. The message was clear: anti-democratic actions are permissible so long as they further conservative ends.

The Republican Party is now in the clutches of Trump’s MAGA movement. After a few years of internecine warfare, the far right emerged triumphant. Trump-skeptical conservatives got bullied out of the Party (see: Ryan, Paul), found themselves facing far-right primary challengers, or kept their mouths shut to save their political careers. America’s asymmetrical political polarization means the Republicans are ever more reliant upon turning out their hardcore supporters, and thus sitting GOP politicians pander to the base and reject extremism at their own peril.

We are hurtling toward another election, and the fragility of American democracy is already on display. Even before a single vote is cast in the 2024 election, Trump’s team has been busy filing a barrage of lawsuits in key swing states, laying the legal groundwork for challenging the outcome of the election. Many of these lawsuits are based on conspiracies about voter fraud or faulty voting machines, and sure, the Democrats will fight them in the courts, but recent evidence shows that Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts put his thumb on the scale for Trump once already. A scenario exists where the Roberts court Bush-v-Gores Trump right back into the Oval Office. A redux of 2016 is also possible, where Trump loses the popular vote by a wide margin while squeaking out a slim Electoral College victory, perhaps aided by the electioneering at the state level. America’s democratic fabric is brittle, indeed.

* * *

If there’s a relative consensus on the far right’s importance to the conservative movement, one issue remains contentious: What, exactly, do we call Donald Trump? While arguing about appropriate definitions might seem like an act of academic navel gazing, words have power.

There are many labels one can apply to Trump. Before the election of 2016, historian George H. Nash described Trump as a “nationalist-populist,” though this phrasing avoided Trump’s obvious authoritarian inclinations. Recent definitional debates have obsessed over a particular question: is Trump a fascist? Some scholars argued that using the word fascist risked framing Trump as a scapegoat, an anomaly, rather than a product of American political culture. After all, as Samuel Moyn pointed out, right-wing authoritarianism has a deep history in the United States, and Trump was relatively constrained by America’s governing structures.

However, January 6 altered the calculus for many scholars, myself included. While watching the mob storm the Capitol, I sent a single-line text to my uncle: “The fascists are trying to take over.” Five days later, Robert Paxton, an emeritus professor at Columbia and noted fascism expert, wrote, “[Trump’s] open encouragement of civic violence to overturn an election crosses a red line. The label now seems not just acceptable but necessary.” Similarly, Yale University professor Timothy Snyder took to the pages of the New York Times to declare, “Trump is a fascist.” In this telling, the history of fascist and reactionary nativist movements within the United States underscores, rather than dismisses, Trump’s fascist bona fides. “In the end,” wrote scholar Sarah Churchwell, “it matters very little if Trump is a fascist in his heart if he’s a fascist in his actions.”

A tone of authoritarian illiberalism permeates Trump’s rhetoric. Recall that Trump proclaimed, “I alone can fix it,” at the 2016 Republican National Convention. More recently, at a Turning Point Action rally, Trump said, if he wins in 2024, “We’ll have it fixed so good, you’re not gonna have to vote.” This is an idea he has trotted out again and again. In the most charitable interpretation, Trump means he will achieve everything that his supporters desire within a second term. But the other, arguably more likely interpretation given Trump’s statements and actions, is that Trump and the Republican Party would dismantle democratic institutions until but a vestige remained. After all, this is the same man who claimed he had “every right” to interfere with the election and called for the “termination of all rules, regulations, and articles, even those found in the Constitution.” Even the country’s foundational documents and institutions are not safe from the wrath of Trump scorned.

Which begs the question: what exactly are conservatives conserving? After all, David Azerrad, a professor at Hillsdale College who once held a leadership position at the Heritage Foundation, proudly told listeners on The Federalist podcast, “We’re not in the business of conserving. We’re in the business of mounting a counter-revolution.” This statement gets to the core of the conservative political culture. In the conservative mind, there is a constant Manichean battle for the soul of America. It is not just about defending pre-existing hierarchies, although that remains a critical component. At its core, modern conservatism contains a spirit of revanchism, a desire to reclaim America from a perceived culture of decadence and decay.

In many ways, the definitional debate revolves around the particular political culture Trump represents. Trump lacks firm ideological coherence in a traditional sense. He is not sitting at home dutifully reading Hayek and Friedman or poring over the latest edition of National Review. He runs on carnival-barker instinct. If a bit fails to energize the crowd, he pivots to the red meat of aggrievement, conspiracies, and violence. At a rally in Claremont, New Hampshire, Trump proclaimed, “2024 is our final battle . . . We will root out the communists, Marxists, fascists, and the radical-left thugs that live like vermin within the confines of our country.” It is not a stretch to say that this sort of linguistic violence, once confined to the pages of far-right magazines and brochures, has never been uttered by a presidential nominee in the modern era. Yet it is one of Trump’s defining characteristics.

In Trump’s world, there is always an “other” to blame. He encouraged “Lock Her Up” chants against Hillary Clinton in 2016, threatened Biden with the possibility of future indictments, and even said people should be jailed for criticizing the Supreme Court. Just recently Trump suggested that unleashing state violence upon the civilian population during “one really violent day” would end property crime. The last suggestion, it is worth noting, is remarkably similar to Senator Tom Cotton’s call to “send in the troops” and violently put down Black Lives Matter protests. This is a key part of Trump’s appeal to his base: a culture of vengeance. Put Trump in power, and he will enact violence upon your enemies. “I am your warrior, I am your justice” Trump told rally goers in Waco, Texas, of all places. “For those who have been wronged and betrayed . . . I am your retribution.”

Back in 2018, David Frum wrote, “If conservatives become convinced that they cannot win democratically, they will not abandon conservatism, they will reject democracy.” Frum is correct, but what he failed to note is that the illiberalism of our present moment emerged from deep roots that permeate the entire conservative movement. A culture of conspiracy, violence, white nationalism, and authoritarianism–such is the natural end point for right-wing populism. If I were to rewrite my conclusion today, I would argue that Trump is not an ephemeral shock, but a culmination. The far-right vanguard emerged triumphant, and the darkness creeping on the horizon edges ever closer.