Eduardo Galeano, Children of the Days: A Calendar of Human History

Eduardo Galeano, Children of the Days: A Calendar of Human History London: Allen Lane 2013. Translated by Mark Fried

Eduardo Galeano’s Children of the Days is neither a calendar nor a history; nor does it cover all of humanity. It is selective, as it has to be, with less emphasis on the East and more on Latin America, as one would expect. It amounts to his own epitaph to his life and work for Eduardo Galeano died in Montevideo, Uruguay, his birthplace, on 13 April 2015, aged 74, two years after the publication of this book. One of his last visits to the US was an appearance at the Pen World Voices festival in New York in 2013.

Children of the Days retains Latin America as a focus, but with reference to ancient Greek and European history—as well as pre- and post-imperial history in African and Australia–always returning to the resilience of the human spirit confronting the brutality of human imperial violence: violence against nature, against animals, against human beings, against women, of elites against the working class, governments and militaries against their own people, fruit companies against their labourers.

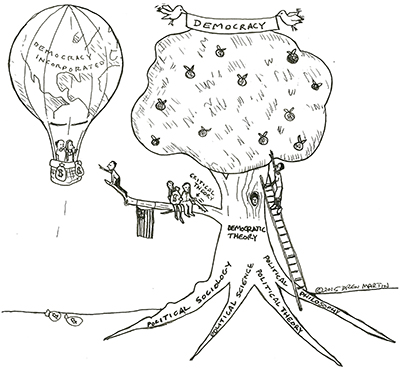

There is whimsy and occasional indulgence (not least in his own pen drawing illustrations) to human greed, folly, madness; the madness of Imperial Spain’s insatiable thirst for gold and silver in the New World, a drive that brought about the destruction of most of the indigenous peoples of Latin America; and which did not even bring more than transitory wealth to Spain itself, which, according to Galeano, was left weakened and depleted already in Cervantes’s seventeenth century, accursed by the over-abundance of precious minerals which found their way into hands of Dutch and Flemish bankers, to whom war debts were owed—eventually financing the building of St Peter’s in Rome.

Wealth brought down the Habsburg royal dynasty, too: Galeano noted in his Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent, published in 1971 (1973 in English), and which became once again a best-seller after President Hugo Chavez presented a copy to Barack Obama in 2009–that the more gold and silver to be found, the greater the poverty (p.32), in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, then as now: “Gold changes into scrap metal and food into poison” (Open Veins, p.2). Nature bestows wealth, which brings about mortality.

Acknowledging his debt to his friend the dependency theorist, Andre Gunder Frank, Galeano’s Open Veins is a poetic rendering of international political economy—while the dependentistas Paul Baran and Celso Furtado are named (p.30), theories of centre-periphery ‘unequal/uneven development’ and unequal exchange’ (pp.28, 16) do not detract from the poetry, become themselves poeticised, as do the ‘external proletariat’ of Engels (p.38), Marx´s Capital Volume 1, and the work of Ernest Mandel (p.28). Despite triumphalist claims by Alvaro Vargas Llosa (et al., Guide to the Perfect Latin American Idiot (2000) with an introduction by Mario Vargas Llosa—yes they are related) and others, repeated in the New York Times in 2014, that Galeano had renounced the content of Open Veins, one only has to read Children of the Days to see that it was the Vargas Llosas of this world who changed their spots—well, Mario Vargas Llosa moved to the right and the sons appear to ape the idiocies of their father—while Galeano was consistent through his long writing life. Galeano’s gripe against Open Veins was merely that it was written – in his view – in heavy academic jargon—except that it is not: compared with most works of international political economy, Open Veins is clear and engaging, impassioned yet scholarly.

In this other 366 days and nights of love and war, the world is still upside down, governed by those who cannot perceive and serve their own interests, let alone the rest of humanity’s. For Galeano, the outcome of colonisation for the indigenous peoples was the “structural violence” conceptualised by Johann Galtung (Open Veins, p. 5) – which continued in a different form imposed by the World Bank as a response to Foreign Direct Investment and loans masquerading as aid in the 1980s and 1990s. While modernisation may benefit some, it comes at the cost of disease and death: “development develops inequality” (Open Veins, p. 3).

The prose poems of Children of the Days (beautifully translated by Mark Fried) are a homage to forgotten heroes—many of them women who fought to defend their land and their people against the colonisers—who might have been airbrushed out of history were it not for Galeano’s last effort on their behalf.

By embracing 4,000 years of history, Galeano reminds us of the continuities of arrogance, racism, prejudice that his Open Veins documented in anticipation of Edward Said´s Orientalism of 1978. In Children of the Days, Christian gods are absorbed into the Aztec, Inca and Mayan gods of nature and of the sun who wreak their revenge for development’s destruction of the forests, plants and rivers, the source of human life. Galeano´s watershed point once again is 1492 which doomed East and West together to 500 years of imperialism, when Jews and Muslims were expelled from Spain in the same year that Columbus sailed to Hispaniola.

Galeano rehabilitates the African gods Iemanyá, Xango, Oxumaré, Ogún, Oshúm, Exú, who accompanied the slaves transported over the Atlantic and on to the plantations, where most perished and from which some escaped into the hills, where their descendants still live (p.73). African gods join Mayan gods and Quetzalcoatl, the Atzec plumed serpent, god of intelligence and self-reflection, god of creation, giver of life (p.23). Galeano laments the loss of books in the burning of the libraries of Alexandria and Baghdad (p.5), and the burning of Mayan books recording eight centuries of Mayan history during the conquest (p.120).

The Guarani tribes of Brazil and the Southern Cone were all but exterminated with the massacre of 1756 (p.48), and the majority of the population of Paraguay was killed in the war of 1864-70 (p.10). General Efraím Ríos Montt of Guatemala presided over the extermination of 440 indigenous communities in the 1980s.

Drawing parallels across time and space, Galeano recalls that aboriginal children were stolen from their parents by the Australian government in the 1950s; then in Argentina, newborn children of murdered revolutionaries were stolen in the 1970s by the military, as were newborn children of murdered Republicans in the Spanish Civil War of 1936-39 (p.53).

Captain James Cook’s failure to colonise Hawaii is celebrated (p.24). Hegel is trashed for writing off the peoples of Latin America for their physical and spiritual impotence; Winston Churchill’s phrases damning the indigenous peoples of both Australia and the Americas are painted back into history: “I do not admit that a great wrong has been done to the Red Indians of America or the black people of Australia … by the fact that a stronger race, a higher-grade race … has come in and taken their place” (p.27).

The modern state and the liberation of the Latin American colonies in the early nineteenth century brought further destruction of the first nations of Latin America—hence the massacre of the last 500 Charrúa in the state of Paysandú in Galeano’s native Uruguay in 1832, shortly after of independence. Similarly in Chile and Colombia Simon Bolívar’s freeing of the Americas from the colonial yoke signalled the enslavement or extermination of indigenous peoples in the name of Republicanism.

Modernisation is synonymous with the state—the developmental state—exemplified by first, the dictators of the 1960s and 1970s in Latin America, and later by the agents of the IMF and World Bank, globalising the remaining independent peoples by offering loans that led to greater dependence in the form of bankruptcy when interest rates rose in the late 1970s through into the 1980s.

The globalization of those who might have preferred to be left outside the modern world continued through the work of the ‘international community’—the development practitioners linked to international non-governmental organizations as well as Western governments who wished to open up markets to Western capital and Western products such as Monsanto’s sterile ‘terminator’ seeds (p.260).

Galeano uses this volume to recall also Western heroes of the twentieth century such as Rosa Luxemburg, communist economist and activist, beaten, bound and drowned in the river in Berlin in 1919; and Stéphane Hessel, French Holocaust survivor and inspiration of the Occupy movement, author of “Indignez-Vous!” “Time for Outrage!” who died in 2011 aged 95.

The plight of domestic animals is not forgotten—human cruelty and speciesism is captured in the cat holocaust of the 14th century in Europe where they burned to death along with the herbalists (witches) who were to be outmanoeuvred by professional physicians when science triumphed over sanity.

Imperialism, Orientalism, Modernisation and Capitalism bring in their wake the destruction of the natural environment, of the Amazon river (p.100), of the sea (Fukushima, p.83), of human health from contamination of fresh water (p. 51), the suppression of women’s spirit and female sexuality (pp.41-2); the deaths of workers and trade unionists (p.84), the silencing of free speech.

Galeano appeals to his readers to follow the lead of the storytellers (Horacio Quiroga), poets, revolutionaries (Pancho Villa, Amilcar Cabral), musicians (Violetta Parra and Bob Marley), the prophets and the environmental campaigners (Chico Mendes) to re-enchant the world, art and nature. God is ever present and the earth is not for sale.

—-

Linda Etchert teaches at Birkbeck College, University of London.