Kant in the 21st Century: On Work, Precarity, and Citizenship in the A.I. Era

We are living in a time of upheaval, as A.I. – and other overlapping crises – are rapidly changing how we work, how we think, and how we learn. One thing we scholars like to do in times of upheaval is to turn to thinkers from other time for insights on our own. So, for example, those working on A.I. have long turned to familiar philosophical toolsets, like Utilitarianism and Kantianism, to solve pesky problems like the ethics of self-driving cars and the potential for A.I. autonomy.

In this essay, I’m going to make the case that Kant’s philosophy – in particular, his political and historical thinking about what it means to live and work in a rapidly changing moment – provides resources for thinking about A.I.’s potential to transform our lives. This is because Kant was an important but underappreciated theorist of labor, and in thinking about the nature of work, he was responding to emergent social and economic changes in his own era. This makes his thinking on work, and their place in his broader philosophical system, particularly valuable resources for our current moment – both, I’ll argue, because of what he got right, and because of what he got wrong.

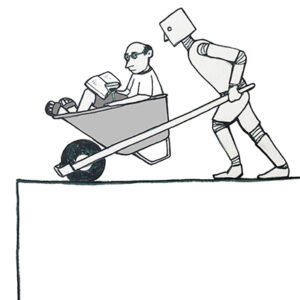

Artist: Drew Martin

Kant was writing during a social revolution that reshaped employment practices in ways that resemble our current A.I.-related upheaval. In the 1770s and 1780s, as Kant was teaching his political philosophy courses and refining his thoughts about the relationship between labor, freedom, and political standing, a famine, revolts, and subsequent legal reforms in Prussia and across Central Europe were dismantling the serf economy, disrupting centuries-long patterns of dependency.[1] Former serfs were suddenly made “free” laborers, working on contract in agricultural contexts and flooding cities like Konigsberg with newly untethered workers. At the same time, the size of the household was shrinking, as the bourgeois household replaced the feudal one; serfs and servants were rapidly becoming contract employees and “day laborers”, precarious 18th century gig workers who could no longer depend on landlords or heads of household to be “fed and protected” (6:315).[2] In many ways, this moment resembled the post-bellum period in the American south, as former slaves found themselves transformed into sharecroppers and day-laborers, and those who could fled the south for Northern cities. In both contexts a rapid shift in the organization of work led to a new class of precarious workers, and new questions about the legal standing and protections to which those workers were entitled. In Kant’s time, these questions would be pressed by the French Revolution, which asserted the importance of recognizing the peasant and working class as free citizens. Accordingly, Kant thought deeply about the relationship between work and freedom, about how legal and economic shifts produced novel forms of precarity, and about what duties the state has to workers. All these insights may be valuable to us as we consider how A.I. is changing the nature of work.

A.I. is automating some kinds of work, making others redundant, and performing others at speeds and scales humans can’t hope to emulate. Some people think that A.I. is about to revolutionize the nature of work, moving us towards a “post-work” society in which we will have to drastically reimagine both our economic practices and the very question of what sorts of activities and commitments make us human. This is a place where Kant can be useful, because Kant thought in systematic ways about work, including how work shapes freedom and organizes our social and political standing, producing predictable patterns of inequality and precarity. To mine Kantian resources for thinking about the future of work, we can examine both his normative arguments – that is, his account of how work should be organized in a just society – and the assumptions that underpin and undercut these arguments. Doing so might help us think in uncertain times and provide us with resources for recognizing how emergent patterns of injustice reflect longstanding practices of inequality.

Work and Freedom

One of the reasons that philosophers still value Kant’s philosophy so highly is because of the systematic ways that he thought about freedom. Kant understood freedom as our central “innate right”, and he conceptualized this freedom across his philosophical system, integrating accounts of moral, political, aesthetic, and epistemic freedom. So, it should perhaps come as no surprise that freedom was at the heart of how Kant thought about work.

From his earliest lectures on political philosophy, Kant described work as an expression of freedom: when we make something, he argues, it is the product of labor and freedom (27:1342).[3] Work is a process that harnesses two kinds of freedom: the freedom of determining a concept – “the thing I have in mind” (27:1342) – or setting the end of my work, and the freedom involved in the production of the thing. He would refine this argument in the 1790s, examining what made work valuable, both intrinsically and instrumentally. Tyler Re has shown how Kant’s claim, the 1791 Critique of The Power of Judgment, that art is “production through freedom” (5:303), develops a normative account of meaningful work as allowing for distinctively human practices of choice, creativity, and judgment.[4] Kant recognizes two distinct conceptions of freedom that operate in work: practical freedom (or the freedom to decide what your projects are) and technical freedom (or the freedom to decide how to do those projects you’ve taken on).

This distinction is particularly valuable for thinking about the varied incursions of A.I. Do A.I. have practical freedom, in that they can choose their own projects and set their own ends? Or do they have technical freedom, or the capacity to decide how to fulfill the ends that are set for it? Technical freedom might also be useful to thinking about the kinds of work we ought to outsource to A.I., to make all work more meaningful. It could help us to identify the kinds of work, or the kinds of tasks, that really are mindless drudgery – like certain administrative tasks, or telemarketing — and to envision outsourcing these tasks to A.I. in ways that made more work more creative. Or, it could help workers to articulate the ways that they find meaning in work that others perceive as drudgery. After all, if work is an expression of freedom, then work is a valuable part of what it is to be human.

Kant also thought work was instrumentally valuable: it allows us to make a living, of course, but paradoxically, Kant also thought it makes leisure possible. Kant thought that “the greatest sensuous enjoyment, which is not accompanied by any admixture of loathing at all, is resting after work’ (7: 276).[5] Without work, there is no leisure.[6]Leisure is “the highest physical good” (7:276) in Kant’s estimation, but also supports both creative endeavors and participation in public reason and the state – all important expressions of freedom.

One of Kant’s most important political innovations was arguing that one’s ability to control the context of one’s labor – to labor “independently” or in ways that are consistent with self-sufficiency and access to leisure – was a prerequisite for political participation. Anyone who “depends on another for their preservation in existence” (6:314) wasn’t independent enough to vote, because their vote could be influenced by this dependency. So, for Kant, it was labor, rather than property, that granted one status as a citizen – and this shaped a meritocratic vision of the state that remains with us to this day. This argument reflects the shifts in labor practices in Kant’s own time, as the dismantling of the landlord system made property less politically determinative, and a new class of free but dependent laborers flooded into Königsberg. It is also a practical argument: to participate fully in the state, citizens would need the time (leisure) and independence (non-dependent labor) to give “public” reasons and participate in shaping collective visions of justice (8:38).[7] Being a citizen meant working in ways that ensured material independence and sufficient leisure time for participation.

But access to leisure was not equally distributed: Kant insisted while the household was the site of leisure for men, it was the site of labor for women; men’s leisure dependent on the labor of women and servants (25:703).[8] This piece of the puzzle is important, because it begins to provide us with tools for situating Kant’s account of work and leisure in his broader philosophical system: a system that included not just reflections on freedom, citizenship, artistic creation and the exercise of reason, but also a social theory about relationships, the infrastructure of everyday life, and the capacities and potential of different kinds of humans, from his reflections on women to his theorization of a hierarchical theory of race. Kant’s thinking about leisure isn’t a mere anthropological observation, but a claim central to understanding his vision of the state – and the role of work within it. Citizens are those with access to the leisure necessary to participate in public reason and the state – but this leisure is made possible by outsourcing certain kinds of labor to others, who then cannot qualify as citizens. In such a system, independence is really a form of interdependence – but if independence is the criteria for citizenship, universal suffrage is impossible.

Employment and Citizenship

If this picture – in which independent citizens outsource certain forms of labor to others so that they can maintain their independence – sounds troublingly inconsistent with the famous Kantian requirement that we never treat others “as a means only”, you’re not wrong. However, it is consistent with Kant’s emphasis on work as a structure that organizes access to public goods. In an era when work itself is under threat, the logic of this argument is worth interrogating.

Kant goes to great lengths in his political philosophy to assure us that organizing political standing in light of the inequalities that shape labour is “rightful” because everyone agrees to them, and therefore, no one is a means “only.” But these patterns of outsourcing track both particular forms of labor – especially caregiving and service labor – as well as certain features of Kant’s anthropological and social theories. These include his assumption that women will do these sorts of labor and thus fail to qualify as “independent,” (6:314) and his claims that non-whites are too “lazy” to work independently (8:176) or lack the “capacities” to set ends for themselves. By embedding these inequalities as “rightful” in his vision of the state, Kant builds a normative theory that embeds hierarchical inequalities and then presents these inequalities as an inevitable feature of a meritocracy in which those who are unequal have somehow consented to their condition.

Most contemporary Kantians respond to this problem by asserting that Kant got something wrong here. Axel Honneth articulates this by arguing that Kant gets the diagnostic picture right – it is in fact the case that patterns of work and material conditions will make some less equal than others – but the normative picture wrong: Kant’s solution is not to insist on universal suffrage, but to formalize this inequality in his “rightful” state, thus heaping formal inequality on top of material inequality.[9] If Kant had solved the problem in the other direction – insisting on universal suffrage and access to public reason – then material or social inequality would not be a justification for political inequality. Ensuring universal access to suffrage and public reason might instead shift the terms of public debate, ensuring that the needs of the materially and socially disadvantaged – and those who do the most denigrated and unappreciated work — become essential features of our conceptions of justice.

Kant’s normative error here is an egregious one, with important implications for his political philosophy. But his error is nevertheless instructive for thinking about both historical and contemporary dilemmas about work, outsourcing, dependency, and equality. We’ve seen that, by linking material inequality and dependency to suffrage and public reason, Kant argued that it is the kind of work one does – rather than, say, the kind of property one owns – that determines one’s political and public standing. There is a particular kind of meritocracy baked into this argument that still haunts us today: the assumption that certain kinds of dependency produce an inequality which is “rightful.” Often, the emphasis is on private dependency: for example, the argument that women didn’t need the vote because their dependence on their husbands or fathers is somehow “rightful.” Contemporary variations tend to emphasize public dependency: see, for example, the ongoing project of welfare reform and “welfare to work” programs in the U.S., which rely on the idea that those who don’t work, or who don’t do the right “kind” of work (because caregiving, even if unpaid, is work) deserve less access to the goods that ensure freedom.

Kant isn’t completely hopeless here: he may not defend universal suffrage, but he does argue for a universal right to poverty relief and provides justifications for public welfare systems.[10] But Kant’s defense of public welfare is premised on lack of access to private dependency: his welfare arguments is aimed at cases like “orphans and widows” (6:326) – those who lack access to the private support of a household (or husband) who ought to support them. As I’ve argued elsewhere, this argument mirrors debates over reparations during American reconstruction, as Congress situated slavery as a form of private dependency that did not, therefore, place any claims for public welfare on the state.[11] We see variations of this logic in contemporary policy that insists upon the prioritization of private remedies to dependency problems over public ones: that one’s employer, for example, should provide access to health insurance, retirement benefits, sick leaves, and childcare services, rather than the state. According to this logic, these are goods that should accrue to people as workers, rather than as citizens. This idea that employment renders people dependent on private employers rather than the state for their “preservation in existence” (6:315), and that such dependency ought to limit access to public standing and public goods, is a Kantian argument – and it’s one we should be particularly attendant to as A.I. reshapes the terrain of work.

Kant and the “Post-Work Economy”

Our current moment of employment upheaval is, like the one unfolding as Kant was writing, characterized by global shifts that are upending long-standing patterns of dependency, entitlement, and stability: old-school full-time employment is increasingly replaced by “gig” work, while A.I. is automating both blue- and white-collar jobs. Both trends threaten (a) the logics of private dependency that organize access to public goods and (b) the role that work plays in organizing our standing as citizens and our expression of our freedom through meaningful contributions. If the proliferation of A.I. moves us towards a “post-work” economy, what happens to these assumptions?

One possibility – which A.I. developers like Sam Altman have long advocated – is a shift to a universal basic income, in which citizens are guaranteed a basic income by the state. Kantians, too, have explored the promise of a UBI model, arguing that if a universal income allows all citizens to gain economic independence, then it does the work of instantiating political equality and thus, by Kantian lights, justifying equal political standing for all.[12] Kant’s argument hinges on the claim that it is independence (or self-sufficiency) that is necessary for full, active citizenship: we can achieve this through certain modes of work, through wealth, and through dependence on the state (which does not make us dependent on the private will of another). Citizens dependent on a UBI would thus be self-sufficient on a Kantian account – and thus, the argument goes, access to such a UBI would ensure that employment-based and domestic dependencies would cease to produce politically disabling forms of dependency.

Arguments for UBI work on one “piece” of the Kantian argument about labor: they provide a mechanism for making all citizens “independent” per Kant’s own technical definition.[13] But they tend to elide the ways that such independence is premised on someone else doing the dependent labor one is therefore giving up: if a UBI frees “us” up to choose our employment, who then takes on the “dirty work” of cleaning up nuclear waste and caring for those who can’t care for themselves? As Martin Sticker has argued, the “us” here is important, and unless a UBI is truly, globally universal, any given UBI scheme is likely to just produce patterns of outsourcing (much like those Kant theorized).[14]A.I. idealists imagine that A.I. can fix this problem by building robots capable of taking on all of this “dirty work”, so that outsourcing can occur without placing persons in positions of (economically coerced) dependency. If this were possible – and experts agree, we are a long way from it – would it solve the problem?

Kant gives us two toolsets to think about this question. On the one hand, insofar as work is a barrier to independence and the time and space to make use of one’s reason – publicly or otherwise – the A.I./UBI revolution is promising: it imagines a world in which we are all dependent on the state – and thus independent – and free to make use of our reason in whatever ways we choose, imaginatively inventing new ways to be human, as Kathi Weeks would have it (2011). I suspect that Kant the man – who was very happy to have a servant make his tea every morning so that he did not have to do it – would yearn for this kind of world. At the same time, Kant also thought of work as an expression of our freedom, a mechanism through which we express our will in the world. This is true whether we work for others, or for ourselves – but putting the arguments together, it’s probably a better expression of our freedom when we work for ourselves: when we have practical freedom, as well as technical freedom. Insofar as the A.I. revolution promises a future world in which we’re all free to drink robot-made, state-supported tea and use our reason to express our freedom and participate in public reason, I think Kant (like many academics) would be all for it.

But I think we also have good Kantian reasons for thinking that this “thin” vision of independence isn’t enough, and that this will haunt us in a “post-work” society. When we conceptualize freedom in a familiarly negative way, in terms of setting our own ends, being free from being bound by others, or choosing the ways in which we will fulfill our projects, we can tend to miss the ways that relationships and collective projects give meaning and shape to our projects, making them both possible and valuable. After all, if freedom is, as Kant puts it, “independence from being bound by others to more than one can in turn bind them (6:237), then it is still a condition in which one is bound. This binding might take the form of expressing our freedom through collective projects and relational practices of care.

This begins to get us to the other way of thinking about the state, and the role of work within it. If, on Kant’s account, we can participate fully in the state when we are independent, we need the state because we are interdependent, and the state is the only mechanism that can provide the rightful infrastructure for such interdependence. Admittedly, Kant got a lot about that infrastructure wrong, because he mapped it onto his own social theory, which assumed that the dependence of women and the inequality of non-whites were structural features that justified limiting public aid, relying on privatized domestic and service labor, and calling all of this “rightful” inequality. (And if this seems unexceptional, it’s because it’s so familiar to us – still – that we have a hard time seeing it as a system, and not just as the “way things are.”[15])

But we can think about the infrastructure that supports freedom differently. This might involve a UBI in a post-work economy, but it would also certainly involve state-supported health care, childcare, sick leave, poverty relief, education, and so on. We might decide that if work is an expression of freedom, people need the opportunity to do meaningful work and contribute to their conditions of interdependence – and we might envision a state that ensures a right to meaningful work and civic contributions, even in the face of an A.I. dystopia. And, of course, we might, like Kant, get this very wrong, by relying on background theories that assume that only certain sorts of people need to express their freedom through meaningful work, and building structures premised on these assumptions.

Kant’s thinking on work reflected a huge social and economic upheaval which is not, in many ways, so different from ours. He got a lot about this upheaval wrong – but he got some of it right, too. If Kant’s arguments are relevant for us, in the 21st century, I think it should be both because of what he got wrong, and what he got right. This means thinking about Kant’s arguments in light of our own questions – and those that informed his own thinking, in his own time. When we do this, we can see Kant as a thinker poised in a moment like our own, aiming to conceive of an infrastructure of freedom in a rapidly changing world – and we can learn from both his innovations and from his mistakes.

Notes

[1] Berdahl, R. M. (2014). The politics of the Prussian nobility: The development of a conservative ideology, 1770-1848 (Vol. 944). Princeton University Press.

[2] In this article, I refer to Kant’s works by <volume number>:<page number> in the standard Academy edition. Citations from volume 6 is the Metaphysics of Morals (1797). Translated and Edited by Mary Gregor. Cambridge University Press: 1996.

[3] Citations for volume 27 are from Feyerabend’s lecture notes on Kant’s 1784 Political Philosophy course. In Lectures and Drafts on Political Philosophy. Edited by Frederick Rauscher. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

[4] Citations for volume 5 are from Critique of the Power of Judgement. Edited by Paul Guyer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

[5] For those familiar with Kant’s account of sex – and the heavy “admixture of loathing” he inserts there – please have a little giggle at his description of the “highest sensuous pleasure” here. Citations for volume 7 are for the Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View (1798). In Anthropology, History and Education. Edited by Günter Zöller and Robert Louden. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

[6] Kant would reinforce this claim with his insistence that when non-white people rest, it is not leisure but laziness, since they do nothing that “one could properly call labour” (8:174 n). For discussion of this passage and its relationship to Kant’s account of work, see Pascoe, J. 2022, Kant’s Theory of Labour, Cambridge University Press, 26-28. See also Lu Adler, H. (2021). (2021). Kant on Lazy Savagery, Racialized. Journal of the History of Philosophy.

[7] Citations to Volume 8 refer to Kant’s political and historical essays of the 1780s. In Toward Perpetual Peace and Other Writings on Politics, Peace, and History. Edited by Pauline Kleingeld. Yale University Press, 2006.

[8] See, too, the passage about non-whites in the last footnote: Kant consistently claimed that non-whites (especially Africans and Americans) were constitutionally too lazy to work, and therefore, that when they rested this was laziness, not leisure (2: 438; 8:176). These are claims not just about work, but about qualifications for political standing. References for Volume 25 refer to Kant’s anthropology lectures, in Lectures on Anthropology. Edited by Allen Wood and Robert Louden. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

[9] Celikates, R., Honneth, A., & Jaeggi, R. (2023). The working sovereign: A conversation with Axel Honneth. Journal of Classical Sociology, 23(3), 318-338.

[10] Varden, H. (2014). Patriotism, poverty, and global justice: A Kantian engagement with Pauline Kleingeld’s Kant and Cosmopolitanism. Kantian Review, 19(2), 251-266; Holtman, S. (2018). Kant on Civil Society and Welfare. Cambridge University Press.

[11] Hartman, S. (1997). Scenes of subjection: Terror, slavery, and self-making in nineteenth-century America. Oxford University Press, p. 119. See Pascoe (2022) p. 44 for discussion.

[12] Pinzani, A. (2023). Towards a Kantian Argument for a Universal Basic Income. Ethical Theory and Moral Practice, 26(2), 225-236; Sticker, M. (2024). Working Oneself Up and Universal Basic Income. Kantian Review, 1-9.

[13] Pascoe, J. (2024). Response to Critics: Kant’s Theory of Labour. Kantian Review, 1-10.

[14] Sticker, Martin. “A Merely National ‘Universal’ Basic Income and Global Justice.” Journal of Political Philosophy, 2022.

[15] Dotson, K. (2014). Conceptualizing epistemic oppression. Social Epistemology, 28(2), 115-138.