Review: Asad Haider, Mistaken Identity: Race and Class in the Age of Trump

Asad Haider. Mistaken Identity: Race and Class in the Age of Trump. London: Verso

Lenin famously said that “imperialism is the highest stage of capitalism”. But then Lenin never saw Facebook.

Social media invites its users to treat all previously intimate and private connections with other human beings as moments for profit-making; all our relationships become commodities. Social media also encourages use to self-brand, to treat our own identities as expressions of that brand. In such a scenario, politics becomes part of our personal brand; witness the rise of performative “wokeness” and even a kind of self-flagellation online, as brilliantly unpacked by Angela Nagle in Kill All Normies. For certain sections of Left-Twitter (a horrible phrase!) this has resulted in a rhetorically radical politics that is simultaneously hollowed out of any meaningful attempt at changing the world.

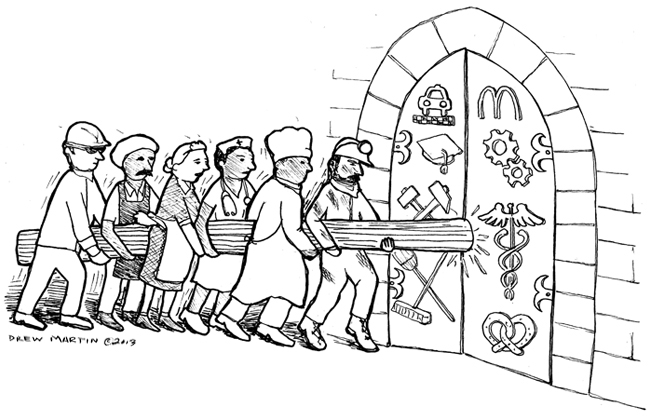

Instead we have what the late Mark Fisher has named “The Vampire Castle”, in which politics is defined by “a priest’s desire to excommunicate and condemn, an academic-pedant’s desire to be the first to be seen to spot a mistake, and a hipster’s desireto be one of the in-crowd.” Where a left politics should combine class, race and gender in a sophisticated and dynamic analysis, we instead get what Fisher called “the sour-faced identitarian piety foisted upon us by moralisers on the post-structuralist ‘left’”. There are several layers of complication here. Race and gender clearly do matter, but so much of how they discussed, online and offline – which is almost the same as saying, how race and gender are today performed – are neither serious nor sophisticated.

In two of the best studies of the contemporary politics of race – The Black Atlantic and There Ain’t No Black In The Union Jack– Paul Gilroy noted the regular tendency of anti-racist politics to slip into essentialized assumptions about black identity (and implicitly also about white identity). The paradoxical conclusion for both anti-racist politics and for the scholarly study of race, is that while the impacts of racism are real, “race” itself is not; it is an ontologically false category of difference. Yet, much of the discussion of a thing called “race” in 2018 goes in a completely opposite direction, with racial identity becoming a fixed, immutable and even essentialised thing. Criticisms of this abound on the Left, sometimes valid ones, sometimes ham-fisted or in denial of the reality of racism (or of sexism). The “Bernie Bro” accusation is an apposite example. Undeniably, there was an anti-Hillary animus that manifested itself in overt online misogyny (visa versa, misogyny found an easy home in anti-Hillary tilts). Yet is also true that these claims were weaponised and used against Sanders’ supporters, cynically painting all with a broad brush. And in the process, the opportunity for a serious re-evaluation of how the left does gender or race was lost, as claims and counter-claims were thrown around and Sanders’ supporters duly defended their candidate. (Though, that Bernie fans seem to have expanded their political affections to include Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, certainly suggests that claims of closet racism and misogyny were mostly made in bad faith).

Something is clearly wrong in the popular discussion of race in the US. And while that has probably never not been the case, the workings of social media and online culture has had an amplifying and distorting impact. Corporations like Twitter and Facebook have forged a symbiotic relationship with more conventional media companies; both seek to generate “clicks”. Promoting intentionally abrasive or controversial content is one easy way to do so. Stoking outrage has become a guaranteed way to draw in web traffic and thus boost advertising revenue.

Asad Haider’s Mistaken Identity appears as an intervention into this morass. Short and readable, the book provides an intellectual genealogy of anti-racism and of the myriad ways in which contemporary anti-racist politics go awry. Haider begins by situating his politics in his own biography, a personal emphasis that works most of the time; the American-born son of Pakistani immigrants, he talks of his inability to settle on a fixed identity. Teenage reading in the classics of American and international leftist literature – Huey P. Newton, Malcolm X, Marx and Engels – reinforced his sense that poverty and racism were conjoined phenomena. Haider’s intellectual development is built on this assumption, that capitalism, class and race have a shared history, echoing Malcolm X’s sense that “It’s impossible for a white person to believe in capitalism and not believe in racism” or Huey Newton’s assertion that “slavery is capitalism in the extreme”. Mistaken Identity thus proceeds to trace the history of those who placed class and race in the same analytic frame and also discusses the ways in which their original ideas have often been hollowed out or pushed to the centre.

“Identity politics” as a concept was coined by the Combahee River Collective, Black feminists who felt (with much due cause) that they were squeezed between white feminists, who ignored racism, and male Black leaders, who ignored sexism. They also sought to incorporate a Marxist theory and praxis and “identity politics” named all of this. For the Combahee River Collective, “feminist political practice meant, for example, walking picket lines during strikes in the building trades during the 1970s. But the history that followed seems to turn the whole thing upside down.” Conversely, “Identity Politics”today is an almost meaningless cypher; used as a slur by the far-right, dismissed as a distraction by old-line leftists, by default it has become the possession of centrist liberals who have taken it far from its radical roots and class politics. Likewise, intersectionality, a term originating in legal studies, has mostly abandoned class and “now has an intellectual function comparable to ‘abracadabra’ or ‘dialectics.’” Yet, for Haider, there is something here worth reclaiming,

Clearly “identity” is a real phenomenon: it corresponds to the way the state parcels us out into individuals, and the way we form our selfhood in response to a wide range of social relations. But it is nevertheless an abstraction, one that doesn’t tell us about the specific social relations that have constituted it. A materialist mode of investigation has to go from the abstract to the concrete – it has to bring this abstraction back to earth by moving through all the historical specificities and material relations that have put it in our heads. In order to do that we have to reject “identity” as a foundation for thinking about identity politics. For this reason, I don’t accept the Holy Trinity of “race, gender, and class” as identity categories. This idea of the Holy Spirit of Identity, which takes three consubstantial divine forms, has no place in materialist analysis. Race, gender and class name entirely different social relations, and they themselves are abstractions that have to be explained in terms of specific material histories.

Identity matters, but is also fraught with potential pitfalls and obstacles. The radical potential of identity politics and intersectionality has degraded into something far less purposeful; “Within the academy and within social movements, no serious challenge arose against the cooptation of the antiracist legacy. Intellectuals and activists allowed politics to be reduced to the policing of our language, to the questionable satisfaction of provoking white guilt, while the institutional structures of racial and economic oppression persisted.” Black identity can just as easily mean an intra-communal solidarity that erases class distinctions and erases the specific demands of the Black working class. And Haider shows a keen grasp of the sheer messiness of this problem.

The existence of this problem is widely recognized, but discussing it constructively has turned out to be quite difficult. Criticisms of identity politics are often voiced by white men who remain blissfully ignorant or apathetic about the experience of others. They are also, at times, used on the left, to dismiss any political demand that does not align with what is considered to be a purely “economic” program – they very problem that the Combahee River Collective had set out to address.

The solution is not to ditch intersectionality or identity politics, but to reclaim and rebuild. Haider peppers his discussions here with emotionally-charged examples of his own experiences with campus organising at UC-Santa Cruz; these kind of campus anecdotes have become a standard feature in discussions of the identitarian left and are not necessarily always that useful. They tend toward defining the phenomenon in terms of its silliest and least mature practitioners. Yet Haider does have a point. He discusses how intersectionality, in the “campus activist usage”, has come to mean a notion that only those who have certain “political subjectivity” (Black, female, gay etc.) have the right to speak on issues pertaining to that identity, something that serves to cut across any possibility of coalition-building. Moreover, positionality slides into an essentialist notion – not just the assumption that only women can “know” gender or only Black people can “know” racism, but also the sense they have access to a truth denied to men or white people.[1] What we end up with is something as deterministic as any vulgar Marxism ever developed!

The intellectual parents of Mistaken Identity are fairly well-known; from Stuart Hall and Paul Gilroy to Judith Butler, Wendy Brown and the Combahee River Collective and the pioneering and polemical whiteness studies of Noel Ignatiev and Theodore Allen. This is all fairly familiar territory but where Haider perhaps does not break any new ground, he does synthesise this array of literature into a useful and slim volume, one that deserves a readership in the current moment.

Notes

1Perhaps the key missing link here, not considered by Haider, is the rise to secular sainthood of Holocaust survivors, as analysed by the late Peter Novick in his 1999 book The Holocaust in American Life, a book that at its most basic level is a discussion of the highly relevant topics of racial violence, memory and victimhood. The assumption that Survivors have access to a special kind of Truth, by virtue of their experiences, does seem to have percolated throughout contemporary American life.

Aidan Beatty is a historian of masculinity, whiteness and capitalism and works at the Honors College of the University of Pittsburgh. His co-edited book, Irish Questions and Jewish Questions: Crossovers in Culture, is out now with Syracuse University Press.