When Voting is a Crime

Federal law mandates that when a voter is turned away because her name cannot be found on the voter rolls, she must be offered the opportunity to cast a ‘provisional ballot.’[i] That ballot is set aside and later counted if election officials can verify the voter’s eligibility. The idea is that no eligible citizen should be denied the right to vote because of a clerical error.

The invention of the provisional ballot and its codification in federal law was one of several half-measures adopted by the U.S. Congress in 2002, to distract attention from the other more serious problems of the 2000 presidential election. That was the election that the U.S. Supreme Court, in full public view, handed the presidency to the loser of the popular vote, George W. Bush. The long-term consequences of the Court overriding democratic norms and waving away routine state vote counting procedures and prerogatives it disdained have been staggering. According to the Costs of War project at Brown University, America’s 20-year failed war on terror, a calamity launched by President George W. Bush in response to the 9/11 terrorist attacks, has cost the nation an estimated $8 trillion, and killed nearly a million people.[ii]

Another grave consequence of the Court’s manipulation of the Constitution to stop the vote counting in Florida is the institution of the Court itself. If George W. Bush had lost the Electoral College in 2000, it is unlikely that he would have been president in 2005, when he nominated two jurists who have been key to the drift of an anti-democratic Court away from respect for the separation of powers and toward a policy agenda championed by the political far Right: John Roberts to succeed William Rehnquist as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, and Samuel Alito, to replace the retiring Sandra Day O’Connor.

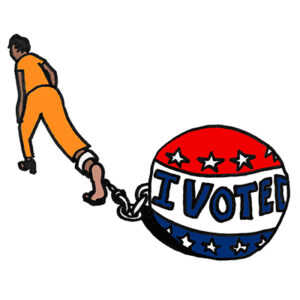

Artist: Drew Martin

Thus, the Supreme Court’s unprecedented interference in the 2000 election, along with the structural distortions in democratic representation of the Electoral College, notched the political Right a win they would build upon in the years to come. The immediate response of the Congress to the Court’s election interference was the enfeebled Help America Vote Act of 2002, which answered the call to ‘do something’ about conditions under which the popular vote loser could win the election by inventing the provisional ballot and other tinkering election administration reforms.

The tragic irony today is that even some of those modest efforts to modernize the nation’s electoral apparatus and to protect voters from losing their votes to administrative mistakes and snafus are being turned on their head. The new landscape for vote suppression has come fully into view, enlivened once again by a Supreme Court jettisoning respect for precedent, this time to neuter the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The Court’s plurality ruling in Shelby County v. Holder[iii] in 2013, invalidated a key provision of the Voting Rights Act that determined which state and local jurisdictions would be subject to pre-clearance, a federal oversight procedure that was the heart and guts of the Act. What millions of ordinary Americans, and especially the most despised and subordinated groups in the society fought and died for for over a century, and won – the right to vote free of racial and gender discrimination – was not the bedrock right that the struggle should have ensured after all.

In the decade since the Court dismantled the preclearance regulatory regime (known as ‘Section 5’), states controlled by Republicans have enacted a series of changes that undoubtedly would have been blocked had the Voting Rights Act’s pre-clearance provisions remained in place.[iv] For example, in anticipation of the hobbling of Section 5, one third of the states fully covered by preclearance enacted photo identification laws either just prior to or immediately after the Shelby County decision. Those laws did not take effect until after the fall of Section 5.[v]

Since then, more states under Republican control have rushed to adopt restrictive identification requirements, and voting rules aimed at increasing turnout, such as early voting and absentee or mail balloting laws, have been curbed, polling stations reduced or moved around, and voter assistance practices outlawed. The current obsession of the vote deniers is the non-existent scourge of migrants coming across the border to allegedly vote for Democrats. The deniers use this unfounded, bizarre claim to sue states for not purging their voter rolls fast enough and for not requiring documentary proof-of-citizenship to register to vote. According to the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law, by the end of 2023, as the nation hurtled toward another sure-to-be momentous presidential election year, voters in 27 states faced barriers to registration and voting that they have never encountered before in a presidential election.[vi]

Which brings us back to the vulnerability of safeguards adopted in the wake of the Supreme Court’s intervention into the 2000 presidential election. How effective are they in the post-Voting Rights Act world the Court helped birth into being? We now live in a world turned upside down and perverted by a foul-mouthed, racist billionaire, former president and his MAGA movement, determined to subvert democracy. The January 6th insurrection showed how far this movement may be willing to go.

The Court, too, continues to flex its anti-democratic muscles. In a shocking development, it granted the president near blanket immunity for criminal acts, as long as they are “official acts” related to presidential “core powers” established by the Constitution.[vii] The Court has also weakened the use of a law against obstructing government proceedings that has resulted in the dropping of some of the charges against some of the hundreds of participants storming the Capitol on that fateful day.[viii] The coup may have failed, but important to our story, the death-by-a-thousand-cuts strategy of eroding access to the ballot carries on, aided and abetted by the U.S. Supreme Court.

But there is something more. The stench of fascism is seeping from beneath the surface of America’s long and ugly history of voter suppression. There is a woman in Texas who understands the threat that stench signals all too well. In 2016, this woman, whose name is Crystal Mason, walked into the church that was her Tarrant County polling place to cast her ballot in the presidential election. She had been released under supervision from federal prison months before after serving four years of a five-year sentence for inflating tax refunds for the clients she worked for as a tax preparer. She had acknowledged her crime and pled guilty, and at the age of 41, was hoping for a new start after being reunited with her children. She drove to the Tabernacle Baptist Church polling place after work at her new job at a bank, not because she was so committed to voting, but rather to quiet the persistent urging of her mother who believes in voting as a civic duty.[ix] She got there just before the voting closed down.[x]

There was a problem, however, with Crystal Mason’s registration records. Her name could not be found on the voting registry, even though she had voted in that same polling place five years before. As she was about to walk away, a volunteer poll clerk did what federal law requires be done: offer Mason the opportunity to cast a provisional ballot to preserve her right to vote until election officials could sort out the registration problem. “’What’s that?’,” she remembered she asked. “And they said, ‘Well, if we’re at the right location, it’ll count. If you’re not, it won’t.’”[xi] Like 4,462 other voters in Tarrant County that day,[xii] Mason, with the help of an election worker filled out the provisional ballot and went home.[xiii] Donald Trump easily carried Tarrant County and won the state of Texas by a comfortable margin, and Mason went on with her life.

Three months later, Crystal Mason was handcuffed at the federal courthouse in Dallas during a routine visit with her supervised release office. She was arrested under Texas’ illegal voting statute, which made it a crime to vote or attempt to vote when the voter knows that she is ineligible.[xiv] After the polls had closed, the 16-year volunteer poll clerk, Jarrod Streibich, remembered that Mason had recently been released from prison and might still be on supervised release for a felony conviction.[xv] He knew this because he was her neighbor. He later told the election judge who was also a neighbor of Mason’s, and the judge, a local Republican Party official named Karl Diederich, passed the information on to the Tarrant County District Attorney, Sharen Wilson.[xvi] No matter that Texas’ apparent criminalization of federal provisional balloting procedures was not contemplated in the federal law creating those procedures;[xvii] Crystal Mason was indicted for illegal voting.[xviii]

The D.A. offered Mason a deal: ten years’ probation instead of likely conviction. But the deal would not have kept Crystal Mason out of jail because it required an admission of guilt which would have violated the terms of her supervised release from the federal tax felony conviction and sent her back to serve the last ten months of her federal prison sentence.[xix] “It was overwhelming,” she told a reporter in 2019. “I felt sick, I felt confused, all I kept saying was ‘Please don’t let me go back to jail.’ I didn’t want to go back inside, I told myself I’d never do anything to risk that.”[xx]

At her trial, Jarrod Streibich, the juvenile volunteer who had turned her in, testified that he witnessed Mason carefully reading the provisional ballot form, which she then signed, falsely attesting to her eligibility to vote as duly registered. He said he was sure she read the part of the form that says being under supervision for a felony conviction was disqualifying because he watched her move her fingers across the lines on the page.[xxi] Mason denied reading the form carefully because Streibich, she said, was helping her with it. She said she was focused on providing the information the form required like her driver’s license number, and going home on that cold and rainy night. She knew the chief election judge, Dietrich, because he lived across the street from her. She said she never saw him at the polling place, and was shocked when he turned up as one of the state’s star witnesses against her.[xxii]

In her defense, Mason’s lawyers called her supervisory release officer to the stand. He testified that he never informed her that she was ineligible to vote while on supervisory release. “That’s just not something that we do,” he said.[xxiii] Crystal Mason never received notices mailed to her home informing her that her registration had been revoked because she was in prison at the time. And prosecutors failed to provide a motive for her alleged crime. “They said I tried to circumvent the system,” she later told a reporter. “And for what? For a [‘I Voted!’] sticker?”[xxiv]

The judge was unconvinced. Crystal Mason was convicted and sentenced to five years in prison. An appeals court denied her appeal and found that the state did not have to prove she knew she was committing a crime when she voted, only that she knew she was a felon.[xxv] This newly invented standard appeared to conflict with what Texas appeals courts found when they reversed the conviction for money laundering corporate contributions into political campaigns of former Republican majority leader of the U.S. House of Representatives, Tom DeLay.[xxvi] The highest criminal appeals court in Texas overturned the lower appeals court in Crystal Mason’s case and sent it back down to the lower court for further review.[xxvii]

In March of this year, that lower appeals court reversed itself and vacated Crystal Mason’s conviction.[xxviii] But the D.A.’s office, which had admitted at the time that their prosecution of Crystal Mason was meant to “send a message,”[xxix] was not done with her. They have appealed her legal vindication, continuing what amounts to nearly eight years of torture of this woman for having cast a provisional ballot that was not counted in a Texas county that voted heavily for Donald Trump.[xxx] The new Republican Tarrant County District Attorney made sure the public understood that the purpose of the state’s pursuit of Crystal Mason was, again, to send a message. It has little to do with any problem with voter fraud. Not one of the 3,990 other people whose provisional ballots were rejected in Tarrant County that election has been prosecuted for illegal voting.

At a public hearing before the Tarrant County Commission in May, D.A. Phil Sorrells defended his decision, stating “I want would-be illegal voters to know that we’re watching…And that we’ll follow the law and we will prosecute illegal voting.”[xxxi] one account, Texas has spent over $100,000 on Crystal Mason’s incarceration alone, with attorneys’ fees on both sides described as “incalculable” by a Dallas former career prosecutor.[xxxii]

Over these last eight years, Mason has suffered emotionally and financially under the cloud of the state’s relentless persecution of her. When she was indicted, her eldest child who had just gone off to college on a football scholarship decided to give up the scholarship to return home to support his mother and family.[xxxiii] After her conviction, she was sent back to federal prison for ten months, missing her daughter’s prom. She has lost numerous jobs because of the notoriety of her case and almost lost her house. She has three children, nine grandchildren and raised her brother’s four children, mostly on her own, all of them at one time or another living in her house in an overwhelmingly White suburb on the outskirts of Fort Worth. The stress has tormented but not broken Crystal Mason. Her story has received national media attention as an egregious case of racially discriminatory voter suppression, which it is.

But her story is also is a signifier of an emerging trend that is at least as troubling for democracy, and that is abuse of legal procedure for political ends. Building on the post-war work of the exiled German Jewish legal scholar and political sociologist Otto Kirchheimer,[xxxiv] the criminologist W. William Minor defines this abuse as

…the discriminatory application of the machinery of criminal justice to the disadvantage of specific individuals or groups because they are perceived as threatening to the power of the established regime. The ‘machinery of criminal justice’ includes lawmaking, police practices, bail setting imprisonment, parole procedures, and all other activities of the criminal justice system, not just the criminal trial.[xxxv]

He emphasizes that politicized justice is what is meted out by the state when state actors feel threatened, and that, “…the perception of threat by those in power is a more salient variable than the actual danger posed by the dissidents.”[xxxvi]

To analyze whether the criminal prosecution of Crystal Mason was an aberrant miscarriage of justice or evidence of a more systematic abuse of legal procedure for political ends, I first re-examined data on voter fraud crime, relying on a database of cases of “proven cases of election fraud” collected by the Heritage Foundation.[xxxvii] I found that over the last eight years, beginning with Donald Trump’s election in 2016, when he claimed he lost the popular vote to Hillary Clinton by three million fraudulent votes cast by undocumented immigrants, there have been approximately 220 voters convicted of some form of illegal registration or voting out of hundreds of millions of votes cast in federal elections. Eight of these convictions were in Texas.

At the same time, since the defeat of Donald Trump by Joe Biden in 2020, half the state legislatures have enacted more than 70 laws criminalizing or banning various activities associated with the voting process. The scale and nature of these highly partisan laws is unprecedented in the modern era. Only three of the 24 states in which Republicans had ‘trifectas’ controlling both houses of the legislature and the governor’s office, passed no laws criminalizing voting since 2020. Five other states with Republican majorities in both houses of the state legislature, but Democratic governors, passed laws criminalizing voting by skirting gubernatorial vetoes one way or another. Only one state controlled by Democrats, Hawaii, passed one law that fits the definition, but this law was meant to clarify an existing statute that prohibits double voting to include casting a second ballot outside the state of Hawaii.

Laws criminalizing voting can be sorted into two basic categories I call ‘first-order criminalization’ and ‘second-order criminalization.’ Criminalization of voting in the first-order includes laws that create new crimes, increase penalties for existing crimes, or re-enact existing crimes, as if to simply make a point. Laws of the ‘second-order’ are those that criminalize or otherwise prohibit activities conducted by others, for example in the registration of voters or in the administration of elections themselves. These include laws that prohibit formerly permitted activities that assist voters in getting registered and casting ballots; other restrictions on third-party voter registration organizations; over-regulation of election administration and election workers, creating in some cases crimes for violating new rules; the tightening up of voter requirements (i.e., no longer accepting student ID’s for voting); the creation of new election crime investigatory agencies or the transfer of investigatory authority from civil to criminal investigators; laws that prohibit the enactment of reforms that increase turnout and election fairness and integrity; the expansion of the rights and authorities of poll observers (inviting voter intimidation); and laws putting proposals to amend state constitutions to prohibit acts already prohibited by statute, such as voting by non-citizens, on the ballot.

Not all of these laws have been implemented, as several are being challenged in the courts. Taken together, however, they push the old game of racist voter suppression into new territory. They are driving vote suppression efforts toward criminal penalties for procedural violations as electoral procedures only grow in complexity. Moreover, they represent a performative style of politics in the age of Trumpism. They turn the manipulation of electoral legal procedure into a drama where bill supporters get to play election cop to the applause of one party’s voter base, no matter the devastation the political theater inflicts on the lives of individuals entrapped in the mess. The surge in laws aimed at ‘stopping voter fraud’ or ‘ensuring electoral integrity’ is not about reducing election crime, since there is very little of that. It’s about ‘sending a message’ about whose votes are worthy and whose should be thrown in the trash. In Crystal Mason’s case, the provisional ballot was not a failsafe,[xxxviii] it was a trap.

The criminalization of voting threatens to use state power to not simply obfuscate electoral rules in making it harder for some people to vote, as in the past, but to proactively criminally prosecute people like Crystal Mason for making a mistake when they become entangled in those rules. If same-day registration helps to expand access to voter registration, it can be shut down before it is enacted; if rank-choice voting provides fairer representation, it too can be thwarted before it is adopted; if a city or town decides it wants legal permanent residents to vote in its local elections; they can be barred by a state constitutional amendment. All of these reforms are now prohibited by law in many Republican-controlled states.

Crystal Mason is a person, a mother, and a grandmother. She works, and managed to keep her house, which is regularly filled with family members she tries to take care of. As her son Sanford told a reporter, “She’s the boss of the company…She provides all of the kids with the things they need.”[xxxix] As a consequence of her ordeal, she has remarkably found the courage and fortitude to become a voting rights advocate, founding a nonprofit organization called ‘Crystal Mason, The Fight Against Voter Suppression’ or just ‘The Fight’ (donations can be made to her organization here: https://www.crystalmasonthefight.org/). But Crystal Mason is also that canary in the coal mine of American democracy that Black people have embodied since the end of Reconstruction more than a century ago.[xl] We should heed the canary’s song.

Notes

[i] 52 U.S.C. § 21082 (2024).

[ii] The Cost of War project’s reports on the financial and budgetary cost of the global war on terror may be accessed here: https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/figures/2021/BudgetaryCosts; their calculations on the human cost in terms of loss of life, may be found here: https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/figures/2021/WarDeathToll.

[iii] 570 U.S. 529 (2013); see: https://www.oyez.org/cases/2012/12-96.

[iv] Jasleen Singh and Sara Carter, “Nearly 100 Restrictive Laws Since SCOTUS Gutted the Voting Rights Act 10 Years Ago,” Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law, June 23, 2023; access October 19, 2024, https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/analysis-opinion/states-have-added-nearly-100-restrictive-laws-scotus-gutted-voting-rights.

[v] Liz Avore, “10 Years Since Shelby County v. Holder: Where We Are and Where We’re Heading,” Voting Rights Lab, June 27, 2023; accessed October 19, 2024, https://votingrightslab.org/2023/06/27/10-years-since-shelby-v-holder-where-we-are-and-where-were-heading/.

[vi] Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law, “Voting Laws Roundup: 2023 in Review,” January 18, 2024; accessed October 19, 2024, https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/voting-laws-roundup-2023-review; see the Brennan Center’s update of this report, “Voting Laws Roundup: September 2024,” September 26, 2024; accessed October 19, 2024, https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/voting-laws-roundup-september-2024.

[vii] Trump v. United States, Dckt. #23-939 (2024); see https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/23pdf/23-939_e2pg.pdf.

[viii] Fischer v. United States, Dckt. #23-5572 (2024). The case concerns the application of a federal obstruction of justice statute, 18 U.S.C. 1512(c)(2), which makes it a crime to corruptly obstruct an official proceeding by altering, destroying, mutilating, or concealing a record, document, or other object with the intent to impair the object’s integrity or availability for use in an official proceeding; by “otherwise” obstructing, influencing, or impeding an official proceeding. The Supreme Court, in a 6-3 decision, concludes that to find a violation of this statute, “…the Government must establish that the defendant impaired the availability or integrity for use in an official proceeding of records, documents, objects, or . . . other things used in the proceeding, or attempted to do so.” According to legal analysts, about a quarter of January 6thdefendants were charged with violating 1512(c)(2). Within that group, over 60 percent have been found guilty of one or more felonies; of the remaining defendants, all were charged with other felony crimes. Only 26 defendants pleaded guilty exclusively to 1512(c)(2) crimes, and some number of others may be able to get their sentences reduced. See Ryan Goodman, Mary B. McCord and Andrew Weissman, “The Limited Effects of Fischer: DOJ Data Reveals Supreme Court’s Narrowing of Jan. 6th Obstruction Charges Will Have Minimal Impact,” Just Security Blog, June 28, 2024; accessed October 19, 2024, https://www.justsecurity.org/96493/supreme-court-obstruction-january-6th/.

[ix] Sam Levine, “Texas Made an Example Out of Crystal Mason – For Trying To Vote,” HuffPost, July 29, 2019; accessed October 10, 2024, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/crystal-mason-prison-sentence_n_5d3b04e8e4b0c31569e9fb94.

[x] Vann R. Newkirk II, “When the Myth for Voter Fraud Comes For You,” Atlantic, (January/February 2022); accessed October 19, 2024, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2022/01/voter-fraud-myth-election-lie/620846/.

[xi] Ibid.

[xii] According to the American Civil Liberties Union Foundation of Texas, which began representing Crystal Mason in 2018, 3,990 of the 4,463 provisional ballots cast in Tarrant County in the 2016 presidential election (89 percent) were rejected, the vast majority (3,942) because the voters were not registered in the relevant precinct. At the state level, 54,850 provisional ballots were rejected out of 67,273 cast (82 percent), with 80 percent of the rejected ballots (44,046) trashed because the voters were at the wrong precinct (citing data from the U.S. Election Assistance Commission; see: Letter from Thomas Buser-Clancy, et al. Director of the ACLU Foundation of Texas, Inc. to Ms. Debra Spisak, Clerk of the Court for the Texas Second District Court of Appeals, received September 26, 2019; accessed October 19, 2024, https://search.txcourts.gov/SearchMedia.aspx?MediaVersionID=a5a65af2-d887-4300-896c-00781618919c&coa=coa02&DT=Other&MediaID=caed7f9d-b597-4cd9-b636-a815001943d7).

[xiii] Sam Levine, “Crystal Mason Was One of Thousands Who Cast a Provisional Ballot; She Was the Only One Prosecuted for A Crime,” Huffpost, August 21, 2019; accessed October 19, 2024, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/crystal-mason-provisional-ballot_n_5d5c5f88e4b0d1e113695972.

[xiv] Tex. Elec. Code § 64.012 (2017). In 2021, due to the national media coverage and the notoriety of Crystal Mason’s conviction, the Texas legislature revised and amended the Illegal Voting statute in ways that would have prevented her from being prosecuted for having made a mistake in casting a provisional ballot. What was called the ‘Mason Amendment’ was added to the law. It states, “A person may not be convicted solely upon the fact that the person signed a provisional ballot affidavit under Section 63.011 unless corroborated by other evidence that the person knowingly committed the offense.” See, Tex. Elec. Code § 64.012(c) (2017). Lawmakers also clarified the mens rea ambiguity issues regarding the statutory construction of § 64.012(a), and reduced the penalty for illegal voting from a second degree felony to a Class A misdemeanor.

[xv] Streibich told Huffpost in 2019, “I knew for a fact that she was just recently let out of prison and that she was a felon.” He also said he knew felons couldn’t vote while on supervised release. See, Sam Levine, “Texas Made an Example,” July 29, 2019.

[xvi] Sam Levine, “She Was Sentenced to Prison for Voting; Her Story Is Part of A Republican Effort to Intimidate Others,” Guardian, June 10, 2024; accessed October 19, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/ng-interactive/2024/jun/10/crystal-mason-voting-intimidation.

[xvii] Mason’s lawyers made this argument in their appeal of her conviction, but the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals rejected it, finding that the federal Help America Vote Act’s provisional ballot rules do not preempt Texas’ criminal illegal voting statute. Mason v. State 663 S.W.3d 621 (Tex Crim. App. 2022).

[xviii] There are conflicting accounts of what, exactly, took place inside the Tabernacle Baptist Church polling place, who was there, who did what, and the sequence of events. The narrative here hews most closely to Crystal Mason’s perspective. For example, she has suggested that she never saw Mr. Diederich at the polling place when she attempted to vote; the State’s brief in Mason’s initial appeal claims it was Diederich, and not Streibich who helped Mason vote the provisional ballot. Mason v. State, No 02-18-00138-CR (Tex. App. 2020).

[xix] Sue Halpern, “How Crystal Mason Became the Face of Voter Suppression in America,” New Yorker, December 18, 2019; accessed October 20, 2024, https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/how-crystal-mason-became-the-face-of-voter-suppression-in-america. According to Ms. Halpern, Mason believed that the federal judge who ordered her back to prison before she could a ruling on her appeal could have given her home confinement instead. “But they were so adamant to send me back to prison,” she told Halpern. “They were so adamant for me to lose my job.”

[xx] Michael Barajas, “The Casualties of Texas’ War on Voter Fraud,” Texas Tribune, September 9, 2019; accessed October 19, 2024, https://www.texasobserver.org/the-casualties-of-texas-war-on-voter-fraud/.

[xxi] Karen Brooks Harper, “Texas Appeals Court Overturns Crystal Mason’s Conviction, 5-Year Sentence for Illegal Voting,” Texas Tribune, March 28, 2024; accessed October 19, 2024, https://www.texastribune.org/2024/03/28/texas-illegal-voting-conviction-crystal-mason/.

[xxii] Michael Murney, “Years of Harassment Led Up to Neighbors Reporting Crystal Mason for Illegal Voting, She Says,” Dallas Observer, Oct. 5, 2021; accessed October 19, 2024, https://perma.cc/FM92-ZS2R.

[xxiii] Mason v. State 598 S. W.3d 755 (Tex. App. 2020).

[xxiv] Newkirk, “When the Myth of Voter Fraud Comes to You,” January/February 2022.

[xxv] Mason v. State 598 S. W.3d 755 (Tex. App. 2020). The court held that Mason’s unawareness of her ineligibility to vote “was irrelevant to her prosecution.”

[xxvi] Delay v. State 465 S. W.3d 232 (Tex. Crim. App. 2014).

[xxvii] Mason v. State 663 S. W.3d 621 (Tex. Crim. App. 2022).

[xxviii] Mason v. State, No. 02-18-00138-CR (Tex. App. –Fort Worth 2024).

[xxix] Prosecutor Matthew Smid stated during Mason’s sentencing hearing that, “The voting system in America is second to none. It is sacred to Americans, and she has violated the sanctity of the process…We respectfully request that this court send a message to illegal voters that if you’re going to violate the sanctity of this system, it will not be tolerated and [you] will pay the consequences.” See, Levine, “She Was Sentenced to Prison,” June 10, 2024.

[xxx] Sam Levine, “Texas to Reconsider Case of Black Woman Sentenced to Five Years for Trying to Vote,” Guardian, August 21, 2024; accessed October 19, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/article/2024/aug/21/crystal-mason-texas-voting-court-case.

[xxxi] Keenan Willard, “Tarrant DA Defends Decision to Pursue Re-conviction of Crystal Mason, Acquitted of Illegal Voting after 8 Years,” NBC 5, May 7, 2024; accessed October 19, 2024, https://www.nbcdfw.com/news/local/tarrant-da-defends-decision-to-pursue-re-conviction-of-crystal-mason-acquitted-of-illegal-voting-after-8-years/3535638/. See the State’s Petition for Discretionary Review submitted to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals here: https://search.txcourts.gov/SearchMedia.aspx?MediaVersionID=3813c658-09e9-4885-8427-b201d09410c4&coa=coscca&DT=PETITION&MediaID=6022489b-7f14-4b78-a300-58437efb47cd.

[xxxii] See Facebook post by Cindy Stormer, former Conviction Integrity Attorney for the Dallas District Attorney’s Office, and a career prosecutor, dated May 12, 2024 (“This was a wrongful conviction…I estimate that the incarceration alone of this mother and grandmother cost taxpayers over $100,000.00. The attorneys’ fees (paid for by taxpayers on both sides) may be incalculable.”); accessed October 19, 2024, https://www.facebook.com/CrystalMasonTheFight/?locale=fi_FI&_rdr.

[xxxiii] Halpern, “How Crystal Mason,” December 18, 2019.

[xxxiv] Otto Kirchheimer, Political Justice: The Uses of Legal Procedure for Political Ends (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1961).

[xxxv] W. William Minor, “Political Crime, Political Justice, and Political Prisoners,” Criminology 12, No. 4 (1975): 385-398, 393.

[xxxvi] Ibid.

[xxxvii] The Heritage Foundation database is not a perfect source of information about voter fraud cases. It casts a wider net by including cases of public corruption, for example, and at the same time is likely under-inclusive of actual instances of voter fraud, though in my experience, not by much. I treat it here as a benchmarking tool, and assume the numbers of cases of prosecuted voter fraud are slightly higher than what the organization tracks.

[xxxviii] The section of the Help America Vote Act of 2002 that establishes that “an individual who desires to vote in person, but who does not present a current and valid photo identification, or other non-photo identification may cast a provisional ballot…” is titled ‘Fail-Safe Voting.’

[xxxix] Levine, “She Was Sentenced to Prison,” June 10, 2024.

[xl] Lani Guinier and Gerald Torres, The Miner’s Canary: Enlisting Race, Resisting Power, Transforming Democracy (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2003).