Eli Zaretsky, Political Freud: A History. New York: Columbia University Press, 2015

Is psychoanalysis kaput ? If not, ought it be put out of its misery? Sigmund Freud and his notorious ‘problem child’ have fallen on very hard times and for reasons having virtually nothing to do with their real merits, argues historian Eli Zaretsky in his latest book. Though a collection of five previously published articles, Political Freud musters a sustained and telling assault on a legion of critics who accuse Freud of straying recklessly from the truth, meaning truth as reckoned by diehard positivists, Big Pharma, and those obliging shrinks who want nothing more than to help clients to ‘fit in’ the social disorder. Go ahead and grow up absurd, as Paul Goodman once put it, so long as you make a buck and no waves. That’s the neoliberal spirit.

Was Freud, the stern sage, really a political animal? Yes, Zaretsky answers, from the very first and in a variety of important ways. That Freud sympathized strongly with the Social Democrats of “Red Vienna’ is the least of it. Zaretsky, author of the splendid Secrets of the Soul, among other works, resurrects this political Freud “to reaffirm the critical element in Freudianism” and to trace out why this dynamic radical core became all but eclipsed. Since the rampant denigration of psychoanalysis from the 1970s onward, Zaretsky argues, we have taken a “huge step backward” in explaining the mysteries and the slippery grip of irrationality in our lives. Yup.

In an achingly ironic fashion Freud, that exquisite connoisseur of ambivalence, should appreciate, the very success of psychoanalysis in the early to mid-20th century generated a milieu that hastened its own decline in an increasingly individualistic epoch. Chapter by chapter Zaretsky “highlights two seemingly antithetical moments: a critical moment when political thinkers and social movements looked to psychoanalysis to clarify the irrational sources of domination and an affirmative moment when Freudianism became submerged in a larger history and appeared to become obsolete.” (p.12) Zaretsky briskly embarks on his mission of integrating “psychoanalysis into the broad matrix of modern social and cultural history,” which he persuasively says “has barely begun” (p. 15)

The first essay, orienting everything to follow, reconsiders Max Weber’s analysis of the role of the Protestant ethic in capitalism, which requires a motivating spirit (if only as a cloak) for its remorseless acquisitiveness. This ‘spirit’ changes roughly as the economy develops, so Calvinist discipline “helped generate the utopian ideology of individuality that accompanied mass consumption (p 18). In a liberal vein, Daniel Bell, among others, pondered the social implications of this dramatic shift in The Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism. This shift entailed a freeing of individuals from the chafing authority rooted in family life, which is in turn rooted in, and reflective of, society. Hence, one cannot speak validly of the inner world in isolation from external events. That essential insight alone makes Freudian psychoanalysis inescapably political. Individuality in the dawning 20th century became ‘the “governing norm” (p. 45), and for navigating our murky inner worlds psychoanalysis became “a theory and practice of those new aspirations for a personal life [and] encouraging an inward development that is the only secure basis for progress.”

What was relished in this early psychoanalytic heyday was the freedom not to discover “universally valid moral rules but “what one wants to do with one’s life,’ although these were hardly mutually exclusive activities. I am reminded of future prominent psychoanalyst Editha Sterba, who as a teenager would bask on a beach poring over a volume of Kant, which was not unusual for rebellious youngsters of her strata at the time. “For psychoanalysis what matters was not worldly success but the state of one’s soul” (p. 28) Psychoanalysis, with its ‘charismatic, anti-institutional origins,” was indelibly subversive, or so it seemed. As Freud recognized, “a bit of unconquerable nature lurks” inside all of us and is ever poised to upset any old institutional apple cart. The eroding of awareness of this crucial and subversive reality is at issue throughout the volume.

Zaretsky’s complains that in the post-war phase the rapid rise of ego psychology, with its conformist “maturity ethic”, arose to dilute and distort the radical crux of Freud’s work. Psychoanalysis purported to study the “durable, unique individual personality,” Zaretsky laments, even as a host of new “intersubjective theories and practices insisted that no such thing ever existed.” The notion of a “personal life interior to the individual was repudiated in favor of an emphasis on flexibility, sociality and sensitivity to difference.” (p. 35) Why? Because in a new era of slick managerial capitalism “image, personality and interpersonal skills, not autonomy, have the highest commercial value.” Mass diffusion, especially in post-war America, ‘democratized and banalized a newly psychological way of thinking.” This is pretty much what Erich Fromm, who I suspect Zaretsky might lump among the ego psychologists, long ago diagnosed as the blight of “other-directedness.”

Zaretsky’s second essay is a fascinating and provocative probe into psychoanalysis as an illuminator of, and ingredient in, the transforming of blacks’ self-image through the Harlem renaissance, the Popular Front and the Cold War eras. The “achievement of genuine subjectivity” by urban blacks “had to pass through a recognition of degradation,” and psychoanalysis became a valuable means for addressing and rectifying ‘internal submission’ and an unmastered past. In music the blues were “a triumph over a shaming culture,’ which “yearned for ’emancipation, including from the racial community itself,” just as many Jews sought a way out of ghettoes imposed not only by hostile others but by tribal Jews themselves. W.E.B. Dubois, Frantz Fanon, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison and other notables were preoccupied with the plight of “double consciousness between self and gaze of others,” defining oneself through the eyes of others, although this tack ultimately seems to have had more to do with G. H. Mead’s profoundly superficial social psychology than with Freudian analysis.

If there was no sex before the 1960s, as poet Philip Larkin drolly averred, there apparently was no ‘self’ before the industrial age either. “Self,’ in this parched rendering, was the human being stripped of volcanic Freudian core and made up instead of little more than the ‘reflected appraisals’ of others – a conceptual recipe for abject or, for that matter, sly conformity. One can imagine why the corporate world warmed to such hollow men and women. Ralph Ellison palled around with neo-Freudian Harry Stack Sullivan whose blunt essay, ‘The Illusion of Human Personality” sums up the stance nicely and icily. Richard Wright, though, recognizing “mental states had a historical and social basis,” duly tried to combine Marx and Freud, and Zaretsky sees this quest pervading the later years of the Popular Front (p. 55, 62) The remarkable Lafargue clinic in Harlem was attentive to the social conditions creating neurosis, and its research into segregation as a public health problem contributed to the 1954 Supreme Court school desegregation decision. Meanwhile, though, in mainstream America, where medical schools and naive empiricism reigned, the Freudian canon slowly but steadily was recruited into “the cold war synthesis as a supposed critic of utopian ideas and advocate of “maturity.” (p 65).

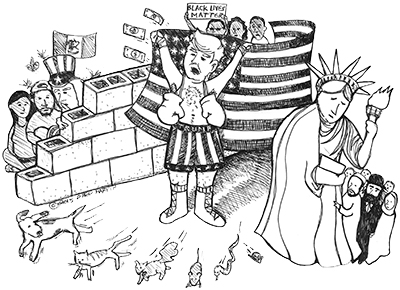

Zaretsky next tackles Freud’s Moses and Monotheism, detecting that Freud’s acute concern with Jewish identity, as an annihilatory World War loomed, was as much about the survival of psychoanalysis and, in turn, the survival of our collective spiritual and intellectual accomplishments. The Nazis were keen to obliterate it all. Today when genial greed uber alles is prized (behold Herr Trump) and civilizational and planetary reversals seem under way at breakneck, we just might sympathize with Freud’s attunement to the fragility of higher values. For Freud, monotheism was an advance which offered “freedom from subordination to the senses and deepens the inner world.” (p. 83). Both monotheism and psychoanalysis, however, were “difficult and even ascetic practices subject to vulgarization and distortion as they took a popular form.”

Like Moses confronting golden calf worshippers, Freud edgily faced Adler, Jung and other dissidents. What was at stake for Freud, Zaretsky explains, “was the subjectivity or inwardness of geistigkeit, through which the mind rose above the instincts and encompassed its own ambivalence.” (p.90) Geistigkeit connotes spirituality in a not necessarily religious sense, and it aligns with the strictly secular meaning of soul in Bruno Bettelheim’s splendid Freud and Man’s Soul. The dissidents, who were well-meaning enough folks, let everyone off easy with palliatives geared to the tempo of glossy, quick fix-obsessed American life. The path to geistigkeit, toward a better-integrated and morally sound human being, was through the resistances, which had to be worked through, not sidestepped. To get to what Lincoln called the better angels of our nature, one has to acknowledge and integrate the hellish aspects of that same nature. No short cuts.

The fourth essay, ‘The Ego at War ‘ is a critique of Judith Butler’s take on 9/11 in Precarious Life, but also of what Zaretsky regards as the vogue-ish and wholly inadequate view that “the ego is formed through object relations and language.” Freud over time moved to ‘analyzing the ego’s defenses rather than interpreting unconscious wishes directly,” but Melanie Klein and others of the object relations school went much further. This is a technically abstruse debate for most readers but Zaretsky carefully lays out what matters in it for the wider culture. Freud wanted to “strengthen the ego while Klein wanted to strengthen personal relations.” Zaretsky pinpoints this latter trend, which will make some readers bridle, as the source of a “weakening of concern with reason and justice and more on intersubjective relations.”

For Kleinians the relationship to the mother – curiously termed an “object” – is the key to ethical responsibility so that the inception of the postwar British welfare state then is attributed to the necessity to protect mothers and children (as if one needed a certified psychoanalyst to account for such a motive). Arising from this is a “maternalist iconography of social democracy” so that a distinguished British Kleinian in June 1940 winds up coining and condemning what she terms a ‘Munich complex,” which is a manifestation of “the son’s incapacity to fight for mother and country.” (p.132) This formulation is plainly daft on so many levels that only Kleinian acolytes (and not all of them) could buy it. The kindest thing to say is that this explanatory mode is seriously incomplete. All experience is hyper-individualized and society is lost sight of.

Judith Butler, an object relations theorist, asks why after 9/11 the collective emotional make-up of America “led away from intersubjective sadness and deliberation and toward vengeful, blind reaction.” Wrong question. While there is much to say in favor of Butler’s analysis of the ‘precariat,” despite her oblique prose getting in the way, Zaretsky notes that Butler treats 9/11 as if every single American automatically slavered for a lashing out in blind revenge. Anyone ever heard of the neocon Project for a New American Century gleefully kicking into gear? Butler commendably urges us toward a broadened circle of solidarity, Zaretsky notes, but this can go in two directions: one is benign and progressive; the other churning out more neoliberal ‘free thinking’ Ayn Rand fans. A Marxist critique is an essential supplement if we are to comprehend our elites’ post-9/11 high jinks. Unlike Butler, the political Freud tradition refuses to treat “dependence and independence as if they were antitheses [and] demonstrates rather the ego reaches down to its earliest, most primal, and essentially immortal dependencies precisely when it is strongest and most independent.” (p.147)

Zaretsky picks up momentum as he barrels along in his final essay which ruefully reappraises the new Left, feminism and a ‘return to ‘social reality.” In the 1960s Herbert Marcuse, especially, re-politicized Freud with an analysis of surplus repression. By the 1970s radical feminism and gay liberation, taking aim (rather understandably) at visible power imbalances, give a Freud they misunderstand the bum’s rush. Psychoanalysis still “embodied powerful sexual and other emancipatory currents that key socializing institutions, above all the family, could not contain,” but this mutinous aspect was muted or ditched as analysts too gradually were enlisted in a project that “weakened traditional authority but substituted the adjustment, labeling and manipulation that the New Left criticized.” (p. 151) Psychoanalysis thereby lost analytical depth. Juliet Mitchell criticized fellow feminists for reducing everything to power relations and promoting culture over biology, which, Zaretsky correctly (I think) accuses, only “paved the way for accommodation with neoliberal thought.” These erstwhile rebels were suckered into a “rights revolution” focused on discrimination against individuals while downplaying structural reform. Thus, again ironically, viewing “the past in terms of power has left men and women powerless” before our worst enemies. Abandoning a notion of authority as entailing an unconscious or intrapsychic dimension was “a gift to neoliberalism.”

How liberated are we anyway? “Can we honestly say,” Zaretsky rhetorically asks, “that a society that is based on release of the instincts, on gratification and on a turning away from guilt, at least at the conscious level, is a freer, more just and more civilized society than the repressive one it replaced?” Zaretsky draws our attention to our blind spots and to the most peculiar ways in which we have colluded in blinding ourselves. A dangerously neglected value of psychoanalysis is that it “enables radicals to look at internal sources of woes, class exploitation within, violence internal to liberalism, misogyny internal to family and violence internal to nation state.” Readers will emerge from Political Freud with a clearer sense of what is lost and must be recovered in the much-maligned psychoanalytic tradition. This brilliant riposte to Freud-bashers ought to be, as they say, on every shelf.

Kurt Jacobsen, Logos book editor, is author of Freud’s Foes: Psychoanalysis, Science and Resistance and of Pacification and Its Discontents, among other works.