Marcuse’s Most Famous Student: Angela Davis on Critical Theory and German Idealism*

*This article is adapted from a chapter in Joy James’s new book, Contextualizing Angela Davis: The Agency and Identity of Icon. We thank Bloomsbury Press for permission to publish this excerpt.

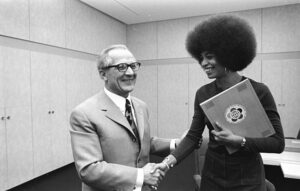

Angela Davis’s interactions with the famous philosopher of critical theory, Herbert Marcuse (1898–1979), shaped not only her university studies but stages within her intellectual and political life. In the first stage, she began as his undergraduate student at Brandeis University in her senior year. She graduated, in the second stage, to attend the Frankfurt School—to which he directed her for advanced study, and vouched for her enrollment. In the third stage, Davis left Germany to enroll in the doctoral philosophy program at UC San Diego with Marcuse as her advisor. Undergrad, MA graduate, doctoral studies: this standard academic trajectory within the professional professoriate was shaped by a (in)famous radical Jewish leftist theorist. Philosophy, critical theory, radical thinking, and praxis with the leftist or post-Marxist theorist revealed transformational stages for Davis: caterpillar, cocoon, chrysalis. Davis was indebted to Herbert Marcuse. Marcuse was indebted to Davis. Their intellectual and political studies would prove beneficial to both.

Artist: Drew Martin

Davis’s An Autobiography says little about Marcuse; this is odd because he is likely one of the greatest influences on her intellectual and philosophical development. Marcuse died in 1979 in Germany; his ashes were interned in a cemetery in the United States for decades (only when a graduate student doing research on Marcuse noted that there was no grave for the Marxist theorist and professor was a ceremony and internment held in Germany—which Marcuse might have protested). Marcuse had a significant impact on Davis’s intellectual formation and an incredible impact on the American and European left. Davis’s association brought her notoriety as a student, but there was also the aura of celebrity and authentic commitment to radical thinking and transformations. Marcuse had many students, including prominent scholars such as Bettina Aptheker, who would become Davis’s colleague at UC Santa Cruz for decades, and notorious radicals and martyrs such as Sam Melville, who was killed at Attica. However, his “most famous student” was a young Black woman who was raised in the segregated south.

“The Man”

Herbert Marcuse1 grew up in a comfortable family in Berlin as a privileged, gifted youth who belonged to a stigmatized ethnic and religious minority. There may have been empathic recognition between the Jewish professor and his Black student. Both came from persecuted ethnic and racial groups whose families still managed to accumulate and maintain status despite devastating race wars. Marcuse was confronted with pogroms and the Nazi Holocaust, Davis with Jim Crow and Klan terrorism. After fighting in the First World War, Marcuse joined the German Social Democratic Party and later completed his doctorate at the University of Freiburg in 1922. He worked alongside Jean Paul Sartre as the research assistant of Martin Heidegger, who became a Nazi.2

Nazism forced Marcuse from Germany in 1933 to Geneva where, at the invitation of Adorno and Max Horkheimer, he joined the Institute for Social Research (Frankfurt School).3 He immigrated to the United States, obtaining citizenship in 1940.4 In New York City, he taught at Columbia University; his research focused on anti-Semitism, racism, fascism, totalitarianism, dissent, persecution, and war—the travail devastating Germany and Europe. After the December 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, Marcuse joined the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) in Washington, DC. When the US entered the Second World War in December 1942, President Roosevelt’s Coordinator of Information, William Donovan, formed the Research and Analysis Branch (R&A) with 900 scholars (which grew to 1,200), which was described as “first-class minds” without “political commitments” eager to serve the war effort. R&A members included Marcuse, Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., Ralph Bunche, seven future presidents of the American Historical Association and five of the American Economic Association, and two Nobel Laureates.5 As would be the case for his “most famous student”—Angela Davis—Marcuse’s radicalism did not preclude him from aligning or working with non-radicals based in academia.

OSS men analyzed Nazi Germany with “scientific objectivity”; their research contributed to the Nuremburg trials.6 (Marcuse, Franz Neumann, and Otto Kirchheimer’s intelligence reports would later be compiled and published, in 2013, as Secret Reports on Nazi Germany: The Frankfurt School Contributions to the War Effort.) In 1945, the OSS dissolved; it was reconstituted in 1947 as the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), which, during the Cold War, would persecute Marcuse, the Black Panthers, and US radicals. There is no indication that the CIA persecuted Davis. Working at the US State Department, Marcuse was pushed out by 1951. After teaching at Columbia and Harvard, in 1954, he settled at Brandeis. There he met and taught Angela Davis and her former Elizabeth Irwin high school classmates. Professor Marcuse candidly observed that his excellent student at Brandeis was gifted but seemed apolitical and disinterested in activism. As an undergrad, Angela Davis presented as the opposite of Marcuse’s more militant white students (who also enrolled in the UC system); these activists were engaged in insurrectionist speech and acts to advance liberation struggles in the 1960s and beyond.7 Some of the white students, such as Bettina Aptheker, participated in the southern civil rights movement, which Davis had avoided. Radicalized by the repressive violence and murders against US activists or Third World liberation movements, some formed underground cells.8 Their names—and deeds—would be eclipsed by “Angela,” who, unlike the Weather Underground and Panthers, engaged in no illegal protests or acts against the state and its police and military forces.

When Marcuse was teaching full-time at Brandeis, he publicly condemned the US imperial wars in Southeast Asia and US racism, two years before Martin Luther King, Jr., delivered his sermon, “Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence,” at Riverside Church in Manhattan, on April 4, 1967 (King’s assassination occurred on the anniversary of that sermon the following year). Dissatisfied with the professor’s public stances for justice and human rights and his opposition to capitalism and imperialism, Brandeis offered him a yearly renewable contract as he reached the retirement age of sixty-five. He rejected it for UC San Diego. Originally, UCSD had a small liberal arts college; its liberal arts departments had three faculty in philosophy and four in literature in 1963. The philosophy department invited Herbert Marcuse to attend its 1964 symposium “Marxism Today.” The Brandeis professor “was well known in academic circles as a social and political theorist, a critic of postindustrial society, and a committed but non-dogmatic Marxist.” Out of the symposium event, Marcuse was invited to teach in the UCSD philosophy department. UCSD offered him a (potentially renewable) three-year “postretirement appointment”9 while Brandeis pushed him toward retirement.

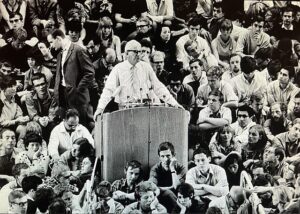

Herbert Marcuse giving a lecture in Berlin, 1967.

Although Marcuse had warned in his text Soviet Marxism, written for the OSS, that the Soviet state had turned “Marxism” into “state Marxism,” or “Soviet Marxism,” that did not deter his doctoral student Angela Davis from joining the CPUSA in 1968. In Marcuse’s analysis, the CPSU presented itself as the stand-in for the proletariat, or for workers and laborers. Hence, in theory, it could speak for the proletariat. If this were true in the USSR, then, logically, it would be true in the United States; i.e., the CPUSA in the states could speak not only for the proletariat but also for the Black masses, because the party knew their interests better than the workers and/or the Blacks—understood as racially oppressed workers—did themselves. The vanguard as party elites would steer the masses and attempt to absorb them within or adjacent to more established organizations. The party under Gus Hall, the same leader that would lock out Davis’s cadre in 1991 when they sought to liberalize the CPUSA and address LGBTQ and feminist rights, saw other leftist organizations as potential competitors. The derisive use of the term “the central committee” came to represent concentrated control over decision-making and anti-democratic leanings within the CPUSA and CPSU. In both formations, party leaders consolidated power into an official “voice” to represent the proletariat. The working class would “rule” via the will of the governing elites. The CPSU, under siege by the West, sought control of its satellite countries; the “Stalinist” CPUSA defended the USSR and its 1955 Warsaw Pact (a response to the formation of NATO); and Davis, after her 1972 acquittal, would serve on the CPUSA central committee for nearly twenty years as that organization expressed the “will” of the people.10

The Frankfurt Institute

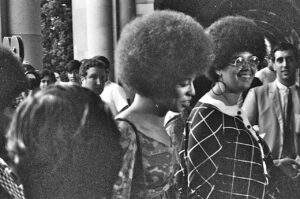

Angela Davis (center, no glasses) enters Royce Hall with Kendra Alexander (right, with glasses) at UCLA for her first philosophy lecture in October 1969. (George Louis)

Three years after participating in the 1962 Soviet-sponsored International Youth and Student Festival in Helsinki, Davis moved to Germany. She had Marcuse’s support. An earlier biographer, Marc Olden, suggests that Davis’s decision to study in Germany was (partially) influenced by her desire to continue—despite parental objections—her romance and relationship with a graduate student from Germany studying American cultural studies, Manfred Clemenz.11 Angela Davis had met her first partner at Brandeis. Manfred returned to Germany with Angela Davis after they both graduated from Brandeis. The couple enrolled in the Frankfurt School to study with Theodor Adorno. They considered marriage, to the consternation of their parents. Black and white parents were apprehensive or hostile to interracial and intercontinental marriage between their gifted children. Biographer Regina Nadelson speculates that while studying abroad at that time, the young Davis also suffered from depression and anxiety and began to see a clinician, the father of her European boyfriend.12 Davis’s and Clemenz’s names appear on graduate student projects and publications, which indicates that they were both enrolled at the Frankfurt Institute at the same time and worked together on class assignments. Both studied with Adorno and Oskar Negt.13

The Institute for Social Research had relocated to Geneva from Frankfurt, Germany, when Adolf Hitler consolidated power in 1933. Two years later, moving to New York City, it merged with Columbia University. No longer working for the OSS, Herbert Marcuse joined the Institute, beginning his US teaching career in 1952 at Columbia. By the 1950s, Horkheimer, Adorno, and Pollock had returned to West Germany, while Marcuse stayed in the United States and eventually secured a position at Brandeis University. In 1953 – around the time Marcuse was pushed out of Columbia, largely due to anti-communism – the Institute for Social Research permanently returned to Frankfurt, West Germany. Recommending that Davis study with Theodor Adorno (1903–69) at the Frankfurt School in Germany, Marcuse wrote a letter of introduction to Adorno. She applied and was accepted. Adorno’s “resignation” as to the possibilities of political struggles and liberation movements led to disagreements between him and Marcuse. Adorno would argue that leftist members of the 1960s student movement were reverting to fascism in their increasingly confrontational protests in Germany. In response, from 1965 to 1967, while Davis was enrolled in her graduate degree program, Marcuse argued that Adorno and other Frankfurt School faculty theorists had given up on the proletariat revolution that Marx had predicted. Not only had the European working class failed to execute their “historic task” of ushering in socialism, many were rapidly becoming fascists. Much of the Frankfurt School’s initial efforts, then, were spent deriving the position from which a critical theory of society was at all possible.14

Failing to sufficiently factor into his analysis the forces of racism/anti-Blackness and patriarchy, Marx incorrectly believed that “the standpoint of the proletariat” would allow one “to decipher the future of capitalism and predict its demise.”15 Adorno—who did a series of public radio addresses in 1960s Germany—developed the “critique of capitalism into a critique of Western ‘instrumentalist’ reason in general, thereby making it unclear not only from what standpoint they were speaking, but also to whom they were speaking.”16 Philosopher Nicole Yokum reflects:

Adorno and Horkheimer’s Dialectic of Enlightenment famously claims that the form of reason dominant in modernity, instrumental rationality (means-end reasoning), helps to explain how the Enlightenment ended up reverting into fascism. According to them, “enlightened” thought contains the seeds of its own demise, insofar as it’s all about subsuming particulars under categories (ignoring and doing violence to what makes them unique), so that things all become replaceable, like laborers in the capitalist economy. They link this to trends in Western philosophy, too. But they take the Holocaust as the emblem of the “regression into barbarism” and they are really not thinking about colonialism and imperialism. Marcuse … was the only one at the time who was taking colonialism into account, at least a little bit.

(December 6, 2022 notes to author)

In Frankfurt, Davis established her credentials as a stellar student. Negt described her as the most outstanding among the 120–150 students attending his seminar. While in Germany, Davis also began organizing with an activist socialist student group.17 (That group, co-led by Manfred Clemenz, would organize from 1970 to 1972 for Davis’s acquittal and decry that she was a “militant” who would have knowingly participated in an effort to clandestinely free Black political prisoners.)

After two years of study in Frankfurt, Angela Davis was preparing for final exams. Observing US rebellions from a great distance, pondering her contributions to a Black freedom movement that she had yet refused to join, her tutelage on violence was shaped by the perspectives of a spectator and a scholar in Europe. The Frankfurt School theorists had experienced and survived Nazi Germany by fleeing to the United States and working for the US Department of State during the Second World War. The US they fled to for safety and democracy was the same nation and imperial project that systemically stole and degraded Black lives. It is likely that the Frankfurt School was not teaching Fanon or Mao, texts the Panthers and militants were studying in their own “schools”; genocide, anti-Black violence and Jim Crow terrorism could be seen as analogs but likely not templates for theory. Davis studied in Europe with German Jewish men grappling with the horrors of Nazism and fascism, but she likely did not fully comprehend those experiences; and, she lacked experiential knowledge in radical organizing and poverty—the experiences of Black laborers, workers, rebels whose insights into US repression expanded but did not fully restructure dominant narratives taught by European scholars.

Defending Marcuse in California

The San Diego Union’s June 11, 1968, editorial “This Is an Order!” demanded that the University of California investigate Angela Davis’s Marxist mentor and advisor, Herbert Marcuse. Marcuse, unlike Davis, was not aligned with the CPSU. Unlike his most famous student, he was not a communist; he was a critical theorist who studied Marx. His critiques and opposition to capitalism and Stalinism rendered him an “enemy of the state”—actually two states: the United States and the USSR. Supporting civil rights and leftist student movements, Marcuse also opposed the US war in Vietnam, CIA and military recruitment on campuses, and university grants funded by the Defense Department. Incensed at his presence on campus, reactionary US veterans escalated their warfare against anti-war and anti-racist activists. They became so reactionary that, though they had fought the fascists and Nazis during the Second World War,18 they were now promoting Nazi ideas and violence during the Cold War against the civil rights movement and the anti-imperialist war movement. Balanced journalism found Marcuse to be “far less active in civil rights and antiwar movements than … Benjamin Spock and two-time Nobel Prize-winner Linus Pauling, who were highly visible in newspapers and on television news.”19 Yet he became a primary target, likely because he was a Marxist. Marcuse had introduced her—after she read The Communist Manifesto in high school—to Marxist philosophy. Mentored for CPUSA leadership, Davis chose orthodoxy and was not deterred by the rigid structure and managerial ethos described in Soviet Ethics, if she even read it. That CPUSA General Secretary Gus Hall was a Stalinist did not negatively impact Davis until the Soviet Union collapsed and Hall sought control by locking out reformers, including Davis and Charlene Mitchell (several hundred members, including many academics, left the party that day).

Angela Davis and the CPUSA were clear; they spoke to the factory working class and the laboring class (Chicano/Latinx farm workers) as well as disaffected middle-class student militants (such as Davis) of all racial backgrounds.20 For Davis’s advisor also had an analysis of culture. For Marcuse, contemporary society was “unfree and by its very nature repressive,” and Marx’s worker as revolutionary agent had been seduced by consumerism and marketing, accumulating stuff, distracted by consumption and materialism; its vanguard role was not predictable. Yokum notes that the Frankfurt School and Marcuse studied cultural products, e.g., radio, magazines, movies, etc., and how consumption of capitalist goods and cultural commodities fed into the working class’s identification with capitalist ideology that masked domination.21 Marcuse discussed how people enamored with apparently elegant or sexy split-level homes rendered their working-class lives just comfortable and luxurious enough to bind them to capitalism.22 Marcuse did not fully note, and likely the CPUSA underplayed, the entrenched white supremacy and anti-Blackness in the United States and global working classes. (Anti-racists overlooked how liberation movements could also become commodities, as images of sleek, attractive, articulate, and affluent Black radicalism became sold as simulacra, e.g., in the Blaxploitation film industry and other sectors.) Contrary to the CPUSA, the white male worker did not constitute the progressive vanguard, as Marcuse’s 1964 One-Dimensional Man warned:

Angela Davis and the CPUSA were clear; they spoke to the factory working class and the laboring class (Chicano/Latinx farm workers) as well as disaffected middle-class student militants (such as Davis) of all racial backgrounds.20 For Davis’s advisor also had an analysis of culture. For Marcuse, contemporary society was “unfree and by its very nature repressive,” and Marx’s worker as revolutionary agent had been seduced by consumerism and marketing, accumulating stuff, distracted by consumption and materialism; its vanguard role was not predictable. Yokum notes that the Frankfurt School and Marcuse studied cultural products, e.g., radio, magazines, movies, etc., and how consumption of capitalist goods and cultural commodities fed into the working class’s identification with capitalist ideology that masked domination.21 Marcuse discussed how people enamored with apparently elegant or sexy split-level homes rendered their working-class lives just comfortable and luxurious enough to bind them to capitalism.22 Marcuse did not fully note, and likely the CPUSA underplayed, the entrenched white supremacy and anti-Blackness in the United States and global working classes. (Anti-racists overlooked how liberation movements could also become commodities, as images of sleek, attractive, articulate, and affluent Black radicalism became sold as simulacra, e.g., in the Blaxploitation film industry and other sectors.) Contrary to the CPUSA, the white male worker did not constitute the progressive vanguard, as Marcuse’s 1964 One-Dimensional Man warned:

[L]iberty can be made into a powerful instrument of domination. The range of choice open to the individual is not the decisive factor in determining the degree of human freedom, but what can be chosen and what is chosen by the individual. Free election of the masters does not abolish the masters of the slaves.23

Disenfranchised “students, artists, Third World peoples, and U.S. racial minorities” embodied Marcuse’s concept of “revolutionary potential.”24

Soviet Marxism condemned Stalinist Marxism (as noted, the CIA supported the text). The CPUSA likely considered Marcuse a pariah but left the verbal bashing to the Soviets or CPSU. The CPUSA was attempting to recruit Marcuse’s student into the CPUSA.

Marcuse’s undergraduate courses, such as “The Present Age,” focused on contemporary thinkers. Under student pressure, he offered a course on Karl Marx but discouraged graduate students from writing on Marx given the conservative job market. A year after Angela Davis arrived on campus, in 1968, San Diego County citizens began to protest Marcuse and his anti-war students. Marcuse had visited Socialist German Student Organization Rudi (“Red Rudi”) Dutschke, who was shot in the head by a reactionary during a student demonstration. Following that gesture of compassion and solidarity, on May Day, leftist students of the University of Paris carried banners reading “Mao, Marx, et Marcuse!” and occupied a lecture hall. International media began to refer to Marcuse as the “Father of the New Left” and “Angel of the Apocalypse.”

That year Governor Ronald Reagan referred to student protestors as fomenting a “climate of violence” on and off campus. In mid-May, Marcuse and his wife Inge Neumann (Franz Neumann’s widow) traveled to Germany and France, where he had been invited to speak at an academic conference. It was while in Berlin that the Marcuses visited the gravely wounded Rudi Dutschke in his hospital room. Soon after their visit, the Bonn Advertiser quoted a “well-informed” unnamed source who claimed that Marcuse had invited the West German student radical to bring his wife and son to San Diego. Furthermore, according to the Advertiser, Marcuse had offered Dutschke a teaching assistantship at UCSD. The story was picked up by Newsweek, the New York Times, and the San Diego Union, which was sufficiently provoked to write its “This Is an Order!” editorial calling for an “investigation.” Even before the Marcuses returned to La Jolla, threatening letters were mailed en mass to the professor, UCSD administrators, and Chancellor William McGill. Marcuse informed New York Times reporters that he and his wife, upon visiting with Rudi Dutschke in the hospital, had recommended to the student leader that he recuperate in the United States with his wife and young son but not enroll in a US university for formal study given the political hostility. (Dutschke did not survive the attack by his right-wing assailant and died soon after the visit.)

While in France in 1968, during student and worker protests, Marcuse attended a UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) conference on Karl Marx in Paris. When student activists occupying the École des Beaux Arts asked him to speak to their gathering, he assented and brought “greetings from the developing movement in the United States”; Marcuse “praised the students for their critiques of capitalist consumerism.”25 Constant negative news about Marcuse drove headlines. The UC administration was being pressured to act. William McGill had been named to the UCSD chancellorship on June 21, 1968. The American Legion lobbied McGill to fire Marcuse and offered to buy out the professor’s contract. The Regents’ agenda for its September UCLA meeting included Marcuse’s reappointment and the “Dehumanization and Regeneration in the American Social Order” course that UC Berkeley’s Free Speech Movement wanted for Panther Eldridge Cleaver, author of Soul on Ice (Cleaver was hired to give ten lectures in thirteen-week course).26 The day before the Regents’ September 19 meeting at UCLA, the Union editorial linked Marcuse to Cleaver, reprimanding the Regents if they permitted

[the] world-infamous Marxist [Marcuse to use] the facilities and prestige of the University of California to preach everything contrary to the American tradition, heritage, and Constitution … [and] Eldridge Cleaver, rapist, revolutionist, and advocate of militant violence, to lecture at Berkeley and Irvine campuses.27

Highlighting ideologically driven attacks from conservative news outlets, The Nation championed Marcuse and critiqued the propaganda that the professor was “fomenting dissent.” It noted that San Diego County had “twenty-one military bases and retired military personnel.” Marcuse had supporters within the academy that resisted a “purge” and the return of McCarthyism. The Pacific Division of the American Philosophical Association elected him its president. UCSD faculty negotiated with the administration for contract renewal while the majority of faculty supported his reappointment. His students began target-practicing to offer him armed protection.28 In 1968, Marcuse’s most promising student began purchasing guns.

According to John Burke, the Union slandered Marcuse for “inciting students,” although Marcuse never sought to influence student opinions. He did not know until later, after they had created defense units and strategies, that his students were taking up arms to counter death threats against him. He spoke with students who sought him out, yet he did not proselytize. Burke recalls Marcuse saying, “if my words are enough to disrupt society, then society is in bad shape.”29 A faculty committee began investigating Marcuse in October, the month UCSD students had invited Eldridge Cleaver to speak to a mass of 4,000 on campus. Cleaver led students in chanting “Fuck Ronald Reagan!”30 Provocative and performative—decades before he (d)evolved into an arch-conservative Christian republican—Cleaver taunted Governor Reagan through the press: “I challenged Ronald Reagan to a duel and I reiterate that challenge tonight, … And, I give him his choice of weapons. He can use a gun, a knife, a baseball bat or a marshmallow. And I’ll beat him to death with a marshmallow.”31

In 1969, Reagan would continue to pressure for Marcuse’s removal. He would turn his ire on the professor’s stellar doctoral student. The Regents were formed in 1868 and for over a century were plagued by corruption, insider dealing on contracts, and considerable unethical and anti-intellectual conduct. After appointing William French Smith as UC Regent in 1968, Governor Reagan demanded that UC Regents fire Davis as a UCLA instructor-professor in the philosophy department. Marcuse was still teaching at UCSD in spite of Governor Reagan and the Regents’ attempts to fire him. Some speculated that Davis was targeted by the Regents because it was easier to destroy her budding academic career, as an avowed member of the CPUSA, than that of an august European left thinker who was not a party member; perhaps attacking Davis was one form of retaliation against her mentor.

Threats against Marcuse increased. That fall, students guarded the entry to his lectures. Students searched unregistered persons who wanted to enter his large survey courses and recruited a friend not enrolled at USCD to sit with his weapon and monitor Marcuse’s large class. The widower Marcuse’s future third wife—after Inge Marcuse’s death—graduate student Ricky Sherover attended Saturday target practice with students who defended Marcuse.32 Whereas Adorno’s students in the Frankfurt School allegedly protested his lack of support for the student movement, Marcuse’s students constituted a vanguard to protect their radical professor.

Rather than denounce conservatives’ attempts to remove him from his teaching post, Marcuse apologized to UCSD Chancellor McGill for the “trouble” he was “causing.” Witnessing what happened to her mentor, Angela Davis would take the opposite strategy the following year when conservatives tried to oust her from UCLA. As reactionaries threatened to kill Davis, she would vigorously challenge the Regents, the governor, rightist ideologies, racism, and sexism.

Angela Davis in Moscow in 1972. (Yuriy Ivanov)

On November 22, the Regents and Governor Reagan met in the same gymnasium where Cleaver had spoken a month before. Several hundred students and faculty, including Marcuse, waited quietly outside. One hundred students watched from the balcony while a vote was taken to determine the status of Marcuse’s course “Social Analysis 139X.” The Regents voted to limit guest lecturers to one lecture in credit courses and struck Marcuse’s course from the list of courses taken for credit. Students walked out and rallied. Marcuse protested the Regents’ action, stating he would no longer serve on administrative committees. On February 3, 1969, the faculty committee investigating Marcuse reported that he ranked highly among sociologists and political theorists, but not philosophers, and was considered a highly gifted teacher; the committee recommended that UCSD renew Marcuse’s contract.33 McGill’s “policy on post-retirement appointments” limited Marcuse’s continuance as faculty; the policy went into effect in June 1970. The February 17 Union ran headlines of McGill’s announcement and the second bombing of San Francisco State College’s administration buildings. The next day it reported protestors firing tear gas and cherry bombs and shattering windows at UC Berkeley. Republican Assemblyman John Stull petitioned for Chancellor McGill’s dismissal. The San Francisco Police Department guarded the regental executive session on McGill’s decision to rehire Marcuse. Reagan advocated that Regents take control over postretirement appointments. Jonas Salk and prominent academics sent a telegram in support of McGill. McGill notified Marcuse of his 1969–70 contract. Marcuse was seventy-two when the contract expired in June; seventy was mandatory retirement age. UCSD, however, allowed him to retain his office on campus and teach informally.

Thousands of students were inspired by Herbert Marcuse, the courageous academic intellectual with the mass appeal of a “rock star” for the New Left. Davis modeled Marcuse. Yet her adjacency to the armed rebellions of Black militants – not her philosophy – allowed her stature to surpass, among the global left, both those faithful to the CPUSA and those derisive of it. She rejected Marcuse’s critiques of the hypocrisies and spiritual emptiness of capitalist consumerism and communist conformity. During the Cold War, Davis was in “good standing” with the Soviets whom the vilified Marcuse criticized. The Soviet’s official paper Pravda castigated Marcuse. Its 11 million readers read descriptions of Herbert Marcuse as a “werewolf,” and denunciations of his criticisms of Soviet rigidity and repression. The Pope hated Marcuse’s call for a revolution based in “erotic liberation”:

In 1969, Pope Paul VI condemned him by name, blaming Marcuse—along with Sigmund Freud—for promoting the “disgusting and unbridled” manifestations of eroticism and the “animal, barbarous and subhuman degradations” commonly known as the sexual revolution. The hostility that Marcuse aroused was ideologically ecumenical.34

Marcuse urged students to think critically about the world and to reject unhealthy social and political orders driven by alienation, technology, and ideology. This did not win him academic friends in the White House or the Kremlin. Rejecting the title “Father of the New Left” and the celebrity status that comes with such appointments, the professor remained a protective and political mentor for Angela Davis, Fania Davis, Bettina Aptheker, Mario Savio, and scores of other students who chose to align with and learn from him.

Marcuse would support Davis throughout her incarceration and trial with a defense mounted by the CPUSA. Angela Davis makes little reference to Marcuse until after her departure from the CPUSA and his commemorations in 2003, when his remains were finally located by a diligent grad student writing about the critical theorist. As noted earlier, the German graduate student realized, through his research, that there was no grave for Marcuse in Germany or in the United States. The industrious student tracked down the philosopher’s ashes to a New England moratorium where they had sat for nearly a quarter of a century. Marcuse had been forgotten. Herbert Marcuse had died in Germany in July 1979 after suffering a stroke; his death had garnered little public notice. With news accounts of a graduate student “finding Marcuse,” interest in him was renewed. Angela Davis was sought to speak about his life and attend his “repatriation” for burial in Germany. (It is likely that Marcuse, who had survived the German Holocaust, might have preferred being buried in England, to the right of Karl Marx rather than on German soil.) Although the CPSU had attacked Marcuse years earlier, Davis appears to have offered no public critique. After her acquittal, and leadership in the NAARPR/CPUSA, she had lost touch with the autonomous thinker. Only decades later would she offer commentary, noting that he “engage[d] directly with ideas associated with movements of that period” and that his “reference to ‘feminist socialism’ in the latter essay [“Marxism and Feminism”] predicted the important influence of anti-capitalist and anti-racist feminism on many contemporary movements, including prison abolition, campaigns against police violence, and justice for people with disabilities.”35

Dissertation Prospectus: Immanuel Kant

Despite turmoil, Angela Davis immersed herself in academic studies. In the 1967 to 1968 academic school year, she completed her doctoral course work with excellent grades.36 She found that she had clearly “benefited both from [Marcuse’s] deep knowledge of European philosophical traditions” and insistence that students stay involved with the world. After course work was completed, Davis began to work on the dissertation. (Davis’s 1974 dissertation on Immanuel Kant from Humboldt University in East Germany is not available in digital format, nor was it made available to researchers who approached Humboldt University; the university cited Davis’s privacy rights.) The dissertation prospectus was titled “Toward a Kantian Theory of Force.”

The dissertation is organized into four parts: I. The Principle of Morality versus the Principle of Legality; II. The State as the Custodian of Coercions; III. The Role of Force in History; IV. A Kantian Theory of Force. Davis writes that in the concluding section, she seeks “to delineate a more far-reaching notion of the importance of force for Kant” by exploring the theories of force in the writings of Fichte, Hegel, and Marx.

Marrying scholarship with activism might or might not be possible in a dissertation theorizing context and addressing contemporary political struggles. Davis’s “Toward a Kantian Theory of Force” focuses on the development of morality through the state or against state repression. She writes: “The importance of the category of force in Kant’s political and moral philosophy has been virtually ignored. Indeed, scant attention has been directed to his Metaphysical Elements of Justice.” Davis notes that she would “remedy this deficiency by shedding some light on these works via the concept of force.” She proceeds to identify the “various functions of force” as “legal coercion, illegitimate violence (crème and revolution) and war as an action prohibited by reason yet necessitated by historical progress.” Her stated problem for interrogation is the “conflict between historically necessary force and its historically desirable abolition.” Davis wants to explore if Kantian political theory and philosophy of history contain or recognize forms of violence that stabilize or reproduce, to undermine his “rationally organized society based on freedom.” The paradox, as she notes, appears to be that “certain forms of violence must prevail” if Kant’s goal of justice is to be achieved.

Angela Davis posits two choices for Kant’s theory, queries which her dissertation would explore and attempt to answer: was Kant’s concept of force homogeneous enough to encompass diversity and antithetical functions, due to the theoretical paradigm of material conditions, or was “a rupture and contradiction within the very concept of force itself” the issue? Kant posits a dualism between morality and legality, theory and history. Discussing self-coercion, coercion, and force, Davis argues that “force is an essential element of freedom. It is the link between the theory and practice of freedom.” Davis writes that Rousseau asserted people “must be ‘forced to be free’.” In a Kantian sense, “the threat of force can bring about external freedom only, i.e., the freedom to act without fear of arbitrary intervention by another.” Only the external conditions exist, so this is not a moral freedom. Moral freedom “is the internal conformity with the moral law” which is not affected by external coercion.37

Angela Davis meets with East German leader, Erich Honecker, September 11, 1972. (Peter Koard)

If Kant argues “that only a legal order can lay the empirical base for the unfolding of morality in the empirical individual,” then, Angela Davis asks, what is his “view of the relationship between morality and legality?” She asserts that legality “can never enter the realm of freedom.” But humans need law in order for their societies to evolve, so Kant’s concept of justice comes from the template of moral law: a belief that “the state should … be a collective moral being.”38 Grappling with a dilemma that she states most philosophers have shirked, Angela Davis tackles “the analysis of the morality-legality dualism” as “the problem of justified coercion by the state.” So the question is: what is the state? As an aggregate of external legal relations based on a social contract, the state is about coercion primarily, and only secondarily concerned with “the moral maturation of its members.” If, however, the state is “a collective moral being”—an idea or ideal—then “its task of protecting the external freedom of its members as a precondition of their moral development is the primary concern.”

The coercive means are secondary to the goal which is moral development; per this thesis, coercion on an evolutionary trek would fade away as humans became more moral, hence Kant’s idealism. Davis writes that her thesis seeks “to determine whether the relationship exists” between the “Idea” or theory of the state and the material state in the twentieth century.

The “objective necessity of history forces men, through war, to make his entrance into … society.”39 In sum, Davis argues that “Kant’s view of history as force” mandates a rejection of his theory of morality as outside of the boundaries of time. If war becomes a precondition for history, then “history and morality are directly opposed to one another”—a fact Angela Davis notes is “untenable.” She asserts that “morality has a historical dimension” unexplored by Kant.40

The dissertation prospectus was submitted to the UCSD philosophy department at a time when Davis observed that Marcuse’s grasp of theory and “the fearless way he manifested his solidarity with movements challenging military aggression, academic repression, and pervasive racism” were unparalleled. That hold on theory helped Davis to hone her theoretical skills to bridge the world of conceptual thought with the world of political activism, specifically politically dissent. Her professor identified academia/theory and activism as distinct partners in a dialectical dance: “Marcuse counseled us always to acknowledge the important differences between the realms of philosophy and political activism, as well as the complex relation between theory and radical social transformation.”41 One can assume that Davis is arguing that the state, in theory, has the right to legal enforcement of its law; and evolving morality, in theory, can emerge in opposition to repressive law; hence both the state and the citizenry that opposes its repression would, in theory, have the “right” to use force. In the state’s case it would be legal; in the militants’ case it would be illegal. Which party, though, possesses the moral high ground? What is the argument for state laws, i.e., legal codes that exist to cultivate morality and ethical behavior in society?

For Davis, Marcuse was a reminder “that the most meaningful dimension of philosophy was its utopian element. ‘When truth cannot be realized within the established social order, it always appears to the latter as mere utopia’.”42 He taught his students to reject the “unmediated translation[s] of theory into praxis.” Marcuse believed that the student rebellions were neither “revolutionary” nor “pre-revolutionary”; rather, he argued, they formed an era in which student militancy “demanded recognition of new possibilities of emancipation” that brought in the immediate moment or the future “fresh air that would certainly not [be] the air of the establishment.”43 It is not clear how Marcuse approached student rebellions as being a catalyst (or utopian element).

Just as Kant’s notion of “man” had gender, racial, and class connotations, Marcuse’s notion of the “student” was shaped by the elite white male students at the Frankfurt School, Columbia, Harvard, Brandeis, and UC San Diego. There is data showing Marcuse being criticized by feminist students for his lack of an analysis of gender. Fania Davis Jordan and Angela Davis were likely his only Black students, or, at least, were the only ones mentioned in Marcuse’s legacy of teaching. The sisters are also Black women, which is a phenomenon under-analyzed in An Autobiography. Yet, their experiences as Black graduate students, of course, did not typify the Black experience in an era in which less than 5 percent of Black Americans had a college or university degree.

Herbert Marcuse, Angela Davis, Fania Davis, and many others in academia faced death threats from racist and anti-Semitic vigilantes and police departments. However, there was always resistance. Demonstrations led by feminist, gay, Black, Chicano, Asian, American Indian, and white anti-war protesters rattled the social order.44 Police forces and vigilantes worked violently to quell unrest. The concept of a Third World campus at UCSD seemed sensible, but the organizing was not sustainable. It had no adequate self-defense component. As anti-war protests on the campus became more heated and violent, repression became more intense.

As the doctoral student worked on her thesis, she found that German (Jewish) philosophy provided a paradigm to analyze moral freedom in the contemporary struggle amidst state and police repression of Black liberation and worker movements. For Davis, radical struggles would deliver progress but not denouement: “Marcuse did not always agree with particular tactics of radical movements of that era, he was very clear about the extent to which calls for Black liberation, peace, gender justice, and for the restructuring of education represented important emancipatory tendencies [that] helped to push theory in progressive directions.”45 One wonders if the ultimate goal is to help theory become more “progressive.”

As Davis studied Marcuse’s An Essay on Liberation (1969) and Counterrevolution and Revolt (1972),46 other women students working with Marcuse began to critique his lack of gender analysis (and edited his 1974 “Marxism and Feminism” paper presented at Stanford University).47 Marcuse’s “An Essay on Liberation” references militant Third World organizations, not the USSR or CPUSA, as the potential future of “revolution”:

In Vietnam, in Cuba, in China, a revolution is being defended and driven forward which struggles to eschew the bureaucratic administration of socialism. The guerrilla forces in Latin America seem to be animated by that same subversive impulse: liberation. At the same time, the apparently impregnable economic fortress of corporate capitalism shows signs of mounting strain: it seems that even the United States cannot indefinitely deliver its goods—guns and butter, napalm and color TV. The ghetto populations may well become the first mass basis of revolt (though not of revolution). The student opposition is spreading in the old socialist as well as capitalist countries. In France, it has for the first time challenged the full force of the regime and recaptured, for a short moment, the libertarian power of the red and the Black flags; moreover, it has demonstrated the prospects for an enlarged basis. The temporary suppression of the rebellion will not reverse the trend.48

Impressed by Marcuse’s optimism, Davis would assert that a key part of his legacy for people was an increased capacity to imagine a holistic and shared future. Marcuse and Davis likely underestimated the rise of reactionary or protofascist forces stemming from the Vietnam War. As students demonstrated against the Vietnam War, veterans—who felt betrayed by a Republican administration that “caved” in to anti-war protesters, and “inferior races”—waged domestic warfare, reconciling with the Nazis against whom they had fought in the Second World War.49 According to Davis, “political imagination reflects the possibilities” for future productive struggles.50 Her professor who had introduced her to philosophy provided relevant lessons: “The insistence on imagining emancipatory futures, even under the most desperate of circumstances, remains—Marcuse teaches us—a decisive element of both theory and practice.”51

Marcuse’s esteem for his most (in)famous student would lead him to give unwavering support when Davis was arrested in 1970 and incarcerated in a small, cramped cell in the Marin County Jail. The professor’s draft notes for the January 31, 1971 NBC interview about Angela Davis evinced a steadfast belief in her innocence and exceptionalism.52 For Marcuse, his undergraduate and graduate student philosopher was assuredly nonviolent. Marcuse noted the complexity and rigor of her educational background, one shared by white European/American elites: “She was my student in philosophy and political theory. In lectures and seminars, we discussed the great texts which have shaped the history of Western civilization: from the Greek philosophers to Hegel and Nietzsche; from the political theorists of ancient Greece to Marx.”53 Marcuse restated previous assertions about her exemplary scholastic achievements—“because it may help to explain her development, her life” and described her as “the best or one of the very best students I had in more than 30 years of teaching.”54

Marcuse humanized Davis to a media and white society that hounded her. To Herbert Marcuse, the young Angela Davis was “an extraordinary student not only because of her intelligence and her eagerness to learn … but also because she had that sensitivity, that human warmth without which all learning and all knowledge remain ‘abstract,’ merely ‘professional,’ and eventually irrelevant.”55 His loyalty to “the left” was unwavering but unconventional. For some, the German-Jewish philosopher was a thorn in the sides of the “establishment.” For others, he rejected orthodoxy in Marxism and critical theory. His philosophical reflections could be considered “abstract scholarship.” Yet his militant students took theory to heart and engaged in political dissent and organizing in order to change the material struggles of liberation. Marcuse was attacked because he “championed student militants against the Establishment … decried ‘increasing repression’ under the Nixon Administration … [and] refused to turn his back on his former pupil Angela Davis.”56 He confides to Davis her impact on his critical thinking:

Frederick Douglass one day hits back, he fights the slave-breaker with all his force, and the slave-breaker does not hit back; he stands trembling [and] calls other slaves to help, and they refuse. The abstract philosophical concept of a freedom which can never be taken away suddenly comes to life and reveals its very concrete truth: freedom is not only the goal of liberation, it begins with liberation; it is there to be “practiced.” This, I confess, I learned from you.57

Some observers felt that Herbert Marcuse’s “consistent espousal of radical action [was] an offense to liberals who have opted for sensible gradualism and modification rather than eradication of the political culture.”58

For fifteen years, Marcuse supported Angela Davis as she evolved from an undergraduate into a graduate student and critical theorist. He and his wife Inge Marcuse visited her in jail and offered support throughout her trial; the couple celebrated her acquittal. Angela Davis did not finish her dissertation on Kant with Marcuse, who was pushed out of UCSD by June 1970. After her acquittal, Davis traveled to East Germany and obtained her doctorate from Humboldt University. Humboldt University’s illustrious alumni include Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels and G.W.F. Hegel, W. E. B. DuBois, Albert Einstein, and Walter Benjamin. The dissertation (as of the last inquiry in 2019 made by a German graduate student returning from studies in Massachusetts) remains sealed and unavailable to the public.

Notes

1 Herbert Marcuse was an intellectual celebrity of activists and the New Left. In 1969, Marcuse’s One-Dimensional Man (1964) sold more than 100,000 copies in the United States and was translated into sixteen languages. Marcuse was internationally greeted by dignitaries and student activists, celebrated or vilified with tag lines of “Marx, Mao and Marcuse” and “unofficial faculty advisor to the New Left.” Condemned by Catholics and communists, as noted earlier, anti-communist Pope Paul VI attacked his books for promoting “disgusting and unbridled” eroticism while communist Pravda’s Yuri Zhukov condemned him as a “werewolf ” and “false prophet.” Apartheid South Africa banned his books.

2 Nazi Martin Heidegger, dissertation adviser and one-time lover of Hannah Arendt, became the rector of the University of Freiburg, where Marcuse received his degree. Heidegger used Third Reich decrees to purge all Jewish professors from the faculty. Survivors who emerged in academia made ideological choices as loyalty oaths to their adopted nations: Marcuse critiqued the United States and advocated socialism and social revolution; Arendt aligned with liberalism.

3 The Frankfurt School (Institute for Social Research in Frankfurt, Germany) emerged during the Weimar Republic (1918–33); its scholars critiqued capitalism, fascism, and communism (Marxist-Leninism).

4 Herbert Marcuse, Sam Keen, and John Raser, “Conversation with Marcuse in Psychology Today,” in Philosophy, Psychoanalysis and Emancipation: Collected Papers of Herbert Marcuse, Volume 5, eds. Herbert Marcuse, Douglas Kellner, and Clayton Pierce (London: Routledge, 2017), 201–2.

5 Assisted by British and Polish intelligence, the Enemy Objectives Unit located Allied bombing targets in Europe, disrupting German oil production; lack of aviation fuel and diesel/gasoline helped to ground Hitler’s Luftwaffe and render German tanks and trucks inoperable.

6 See Franz Neumann, Herbert Marcuse, and Otto Kirchheimer, Secret Reports on Nazi Germany: The Frankfurt School Contribution to the War Effort, edited by Raffaele Laudani (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013).

7 Naomi Jaffe joined the Weather Underground, which bombed the Pentagon (no injuries to humans) over its war atrocities against Vietnam and US support for apartheid in South Africa, and its hiring mercenaries and assassinations of liberation movement leaders in the Third World. Mario Savio and Bettina Aptheker were leaders in the 1964 Berkeley Free Speech Movement. Anarchist bomber Sam Melville was killed in the 1971 National Guard retaking of the Attica Prison in New York.

8 Following the September 1971 suppression of the Attica rebellion, Ms. Magazine published a letter from Jane Alpert—Swarthmore grad, and Columbia university grad student—former partner of Sam Melville, whom she accused of domestic abuse. Ms. Magazine editors published Jane Alpert’s letter condemning Melville and the imprisoned men who died in Attica as “chauvinist pigs” who “would not be missed.” It is unclear if Ms. was outraged not only by patriarchy but also by rebellions against the state waged by the impoverished or imprisoned. In Ms., Albert celebrated the deaths of rebels by prison guards.

An “open letter” from Miss Alpert, which was published by Ms. magazine last year, had urged women to renounce left-wing causes and “work for ourselves.” In recounting her own progress from “serious militant leftist” to a radical feminist, she had urged women to break from such “male supremacist” groups as the Weathermen. Melville, Alpert and two others—protesting the war and genocide in Vietnam—had engaged in a serial bombing campaign. They were arrested on November 12, 1969, “after a bomb exploded at the Manhattan Criminal Courts Building at 100 Centre Street—the eighth Government or corporate building to be struck by the group since a wave of bombings began on July 26, 1969.”

Albert went underground in May 1970, three months before Angela Davis disappeared into her underground. See Robert Mcg. Thomas Jr., “Jane Alpert Gives up after Four Years” (New York Times, November 15, 1974, https://www.nytimes. com/1974/11/15/archives/jane-alpert-gives-up-after-four-years-jane-alpert-surrenders-here.html); Lucinda Franks, “The 4-Year Odyssey of Jane Alpert, From Revolutionary Bomber to Feminist” (New York Times, January 14, 1975, https:// www.nytimes.com/1975/01/14/archives/the-4year-odyssey-of-jane-alpert-from-revolutionary-bomber-to.html).

9 Judith Moore, “Marxist Professor Herbert Marcuse’s Years at UCSD Were Marked by Crisis, Strife, and Controversy: Angel of the Apocalypse” (San Diego Reader, September 11, 1986).

10 The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica, “Warsaw Pact” (Britannica, updated December 23, 2022, https://www.britannica.com/event/Warsaw-Pact).

11 Marc Olden, Angela Davis: An Objective Assessment (New York: Lancer Books, 1973). Manfred Clemenz (1938–) studied American literature at Brandeis as a graduate student. His online bio states that he received a doctorate in sociology and philosophy after studying with Adorno and Horkheimer at the Frankfurt School, specializing in analyses of fascism and racism. He became a professor of sociology and later a psychotherapist. Within Germany, he and other graduate students organized for Davis’s defense, 1970–2, finding it absurd that their former classmate had politics similar to those of Black revolutionary militants. See https://www.manfredclemenz.de/.

12 Regina Nadelson, “Who Is Angela Davis?” (New York: Peter H. Wyden, 1972).

13 See note 11 on Clemenz, who co-led a German Solidarity Committee for Angela Davis during her trial. Author’s papers.

14 Georgia Warnke, “Feminism, the Frankfurt School, and Nancy Fraser” (Los Angeles Review of Books, August 4, 2013).

15 Warnke, “Feminism, the Frankfurt School, and Nancy Fraser.”

16 Warnke, “Feminism, the Frankfurt School, and Nancy Fraser.”

17 Angela Davis, “Explorations in Black Leadership,” interview by Julian Bond (C-Span, April 15, 2009, https://www.c-span.org/video/?328898-1/angela-davis-oral-history-interview).

18 See Kathleen Belew, Bring the War Home: The White Power Movement and Paramilitary (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2018).

19 Moore, “Marxist Professor Herbert Marcuse’s Years at UCSD.”

20 Warnke, “Feminism, the Frankfurt School, and Nancy Fraser.”

21 December 2022 conversation, Nicole Yokum and Joy James.

22 Nicole Yokum, written communique to author, December 2022.

23 Moore quoting Marcuse in “Marxist Professor Herbert Marcuse’s Years at UCSD.”

24 Moore, “Marxist Professor Herbert Marcuse’s Years at UCSD.”

25 See Angela Davis, “Angela Davis on Protest, 1968, and Her Old Teacher, Herbert Marcuse” (Literary Hub, April 3, 2019, https://lithub.com/angela-davis-on-protest- 1968-and-her-old-teacher-herbert-marcuse/).

26 Moore, “Marxist Professor Herbert Marcuse’s Years at UCSD.”

27 Moore, “Marxist Professor Herbert Marcuse’s Years at UCSD.”

28 Moore, “Marxist Professor Herbert Marcuse’s Years at UCSD.”

29 Moore, “Marxist Professor Herbert Marcuse’s Years at UCSD.”

30 Moore, “Marxist Professor Herbert Marcuse’s Years at UCSD.”

31 Richard McDonough, “Eldridge Cleaver: From Violent Anti-Americanism to Christian Conservativism” (The Postil Magazine, February 1, 2021, https://www.thepostil.com/ eldridge-cleaver-from-violent-anti-americanism-to-christian-conservativism/).

32 Moore, “Marxist Professor Herbert Marcuse’s Years at UCSD.” At the age of fifty-nine, Mrs. Inge Werner Neumann Marcuse, wife of Prof. Herbert Marcuse, the political philosopher, died of cancer in La Jolla, Calif. Born in Madgeburg, Germany, she had accompanied her first husband, Prof. Franz Neumann—a professor at Columbia University—to the United States in 1936. He died in 1954. She then married Professor Marcuse and taught French in California. “Mrs. Herbert Marcuse,” New York Times Obituary (August 2, 1973, https://www.nytimes.com/1973/08/02/ archives/mrs-herbert-marcuse.html).

33 Moore, “Marxist Professor Herbert Marcuse’s Years at UCSD.”

34 See Whitfield, “Refusing Marcuse.”

35 Davis, “Angela Davis on Protest.”

36 See Davis, “Angela Davis on Protest.”

37 Kant quoted in Angela’s dissertation prospectus. Author’s papers.

38 Kant quoted in Angela Davis’s dissertation prospectus, 3. Author’s papers.

39 Kant quoted in Davis’s dissertation prospectus. Author’s papers.

40 Angela Davis’s dissertation prospectus, 3. Author’s papers.

41 Davis, “Angela Davis on Protest.”

42 Davis, “Angela Davis on Protest.”

43 Davis, “Angela Davis on Protest.”

44 California students were not the only ones in rebellion. Columbia University’s radical white students rioted against the Vietnam War and the social order. Some were beaten brutally by police. One jumped out of a window and broke an NYPD officer’s back. Black students occupied another building to protest against a proposed segregated gym in Morningside Park that divided the campus from Harlem. During the violent fracas, Black police officers secretly led them down back corridors to off-campus safety. Each segment of students appeared to be organizing in separate silos. University administrations increasingly deployed riot police and the National Guard against student protestors in order to control campuses.

45 Davis, “Angela Davis on Protest.”

46 Alongside his wife, whom he does not name, Marcuse acknowledged colleagues who offered helpful critiques for An Essay on Liberation. All of the commentators are professors at the most elite US institutions: UC Berkeley’s Leo Lowenthal, Princeton’s Arno J. Mayer, and Harvard’s Barrington Moore, Jr. See “Acknowledgments” in Herbert Marcuse, An Essay on Liberation (Boston: Beacon Press, 1971).

47 While Angela Davis was completing her dissertation at Humboldt University and touring for her 1974 autobiography, Marcuse referenced her work in his university lecture on “Marxism and Feminism”: “advanced capitalism gradually created the material conditions for translating the ideology of feminine characteristics into reality, the objective conditions for turning the weakness that was attached to them into strength, turning the sexual object into a subject, and making feminism a political force in the struggle against capitalism, against the Performance Principle. It is with the view of these prospects that Angela Davis speaks of the revolutionary function of the female as antithesis to the Performance Principle [a social norm “based on the efficiency and prowess in the fulfilment of competitive economic and acquisitive functions,” 279], in a paper written in the Palo Alto Jail, “Women and Capitalism,” December, 1971.” See Herbert Marcuse, “Marxism and Feminism” (Women’s Studies 2, 1974: 279–88, http://platypus1917.org/wp-content/ uploads/archive/rgroups/2006-chicago/marcusemarxismfeminism.pdf), 284.

48 Marcuse, An Essay on Liberation.

49 See Belew, Bring the War Home.

50 Davis, “Angela Davis on Protest.”

51 Davis, “Angela Davis on Protest.”

52 See Marcuse, draft notes for interview with NBC, January 31, 1971 (author’s papers).

53 Herbert Marcuse, draft notes.

54 Marcuse, draft notes.

55 Marcuse, draft notes. The UCSD Alumni Magazine recognizes its impressive alumna: “Marcuse’s best-known student, the civil rights activist Angela Davis, M.A. ’69.” In the decades that followed her acquittal, Angela rarely publicly spoke of Marcuse until memorials and media following the repatriation of his remains brought him back into the spotlight.

56 See Marcuse et al., “Conversation with Marcuse.”

57 Quote reprinted in Robert Gooding Williams, “Douglass’s Declarations of Independence and Practices of Politics.”

58 See Marcuse et al. “Conversation with Marcuse.”