No Democratic Theory Without Critical Theory

Since the fall of totalitarian regimes after World War II and the Cold War, mainstream sociologists have fundamentally assumed that the political system of democracy is the only desirable political model to facilitate decision-making in both advanced capitalist countries and developing countries in what used to be referred to as the Third World.

Yet this de-facto utopian depiction of 21st century political life has been marred by repeated critiques of actually existing democracies from mainstream sociologists, among many others. The problem, for these sociologists, is that actually existing democratic processes are increasingly characterized as undemocratic (Cairns and Sears 2012; della Porta 2013; Perrin 2014). This tension between on the one hand, the expansion of democracy globally, and on the other hand, the increasingly undemocratic character of this democratic expansion constitutes the central paradox that sociologists of democracy seek to understand and rectify. For mainstream sociologists, integrating participatory and deliberative democratic processes into the liberal democratic system constitutes the normatively preferred path to democratic rejuvenation. Yet, to what extent can this call for quantitatively more and qualitatively better participatory and deliberative democratic procedures be sustained in the face of a neoliberal economic system that not only subverts the responsiveness of democratic institutions to popular influence but also colonizes those democratic citizens themselves and transforms them into minions of the capitalist system, willing to protect the interests of capital over the interests of the public?

The problem is that modern societies, as democratic societies, contain existing power structures, such as ideologies, institutions, parties, and associations that have resisted the formation of a more substantively democratic society responsive to public participation.[pullquote]The problem is that modern societies, as democratic societies, contain existing power structures, such as ideologies, institutions, parties, and associations that have resisted the formation of a more substantively democratic society responsive to public participation.[/pullquote] In fact, American society has never been a democratic society if democracy is defined as a political system that channels the collective popular will of the entire populace directly through the governmental apparatus. Instead, the labeling of the American political system as democratic refers to a narrow and specific definition of a hollowed-out “democratic method” and serves to conceal the extent to which American society resists substantive democratization (Schumpeter 1942). Mainstream sociological democratic theory that seeks to counter the democratic method and advocate for a more substantial democracy risk positing visions of democracy that are incompatible with the operation of politics in actually existing democracies (e.g. Polletta (2013) calls for an increase in the participation of citizens in a political system that is less and less responsive to citizen participation). In effect, mainstream sociological democratic theory makes assumptions about the existing political system without situating their claims within the socio-historical circumstances existing in that particular society. This means that to the extent to which there is any kind of democratic theory within mainstream sociology, it has stagnated in its ability to capture the highly dynamic changes in society that influence democratic processes, which thereby undercuts mainstream democratic theory’s relevance to theorizing political processes occurring in American society.

Mainstream vs. Critical Sociological Democratic Theory

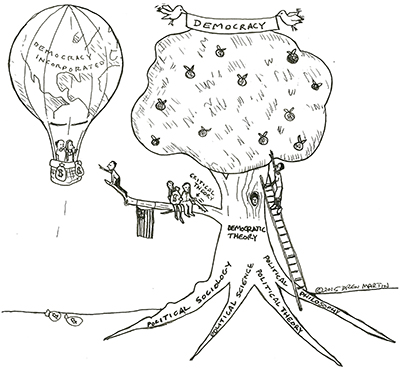

Within the larger tree of democratic theory that is characterized by the contributions of political science, political theory, political philosophy, and political sociology, this essay focuses on the specific branch of political sociology that concerns democratic theory. Because no established sociology of democracy exists as a unifying framework for researching democratic processes, sociologists remain fragmented in their approaches to democratic theory. On the one hand, mainstream sociological democratic theory is characterized by those political sociologists who tend to utilize normative and empirical frames to understand the quality of actually existing democratic processes (Cairns and Sears 2012; della Porta 2013; Perrin 2014). These mainstream political sociologists subscribe to democracy as the superior normative political model and construct empirical possibilities as a function of the theories they employ, rather than posit empirical possibilities as a function of actually existing circumstances. The dilemma, therefore, is that the problems and solutions prescribed to rectify democracy are a dependent upon the particular frame being utilized to examine democracy.

In comparison to this mainstream sociological approach stands a critical sociological approach to democratic theory. This critical theory of American democracy in the 21st century recognizes the potential detrimental bearing concrete socio-historical circumstances have on the attempt to theorize modern democratic societies. In effect, mainstream sociological democratic theory does not sufficiently consider how concrete socio-historical circumstances affect the formulation of their normative and empirical theories of democracy. As a result, mainstream sociology’s contribution to democratic theory has been limited and even more so, may subvert the attempt to apprehend the actually existing processes of modern democratic societies, specifically American democracy.

This critical orientation to democratic theory stems from the foundational work of Critical Theory as it was first articulated by Horkheimer (1937) in Traditional and Critical Theory and developed further by Dahms (2008) in No Social Science Without Critical Theory. In his article, Dahms attempts to reclaim the lost programmatic core of the first generation of the Frankfurt school. Dahms urges practitioners of social theory to pay attention to the concrete gravity that specific socio-historical circumstances impose on the attempt to understand socio-historical circumstances. For mainstream sociological democratic theory, this call has fallen on deaf ears. Mainstream sociology therefore operates under theoretical assumptions whose validity they do not question with regard to the functioning of actually existing democracy under concrete socio-historical circumstances.

The work of Andrew J. Perrin, who is the prominent chair of the theory section of the American Sociological Association, is exemplary in this regard of mainstream sociological theorizing. Perrin’s (2014) most recent work, American Democracy: From Tocqueville to Town Halls to Twitter, fits well within the larger cultural turn that has emerged within the discipline of political sociology. Perrin utilizes a Tocquevillian and culturally oriented framework for understanding the contours of American democracy. In this way, Perrin claims that he is not studying the government, but “the polity,” which denotes an implicit connection between the people and the processes of government (p. 3). Perrin’s sociology of democracy therefore seeks to theorize the role of ‘the people’ in actually existing American democratic society.

In emphasizing the cultural dimensions of democracy, Perrin neglects the economic dimensions. In giving almost no mention at all to the economy in his examination of democratic processes, Perrin therefore implicitly assumes the independence of the political from the economic, as if they were separate modes of power. “Democracy, in other words, is not only, or even primarily, a political phenomenon. It is also a deeply social, institutional, cultural, and historical phenomenon” (p. 13). Apparently for Perrin, democracy has no connection to the economic realm at all.

It even appears as if Perrin goes to lengths to avoid talking about the economy, such as when he states, “Civil society is the area of life that isn’t governed by economic markets, private family life, or government actions” (p. 57). Although Perrin never clarifies the relationship between civil society and the economy, the original democratic theorist of the public sphere, Habermas (1962), never neglected the economy’s impact, and ultimately its perversion, of civil society, the public sphere, and democratic processes. Even in Perrin’s (2014) discussion of “efficacious citizenship”, or ways that citizens influence political processes that venture beyond voting, Perrin lists such actions available to citizens as to “circulate and sign petitions; answer public opinion pollsters; organize, join, and participate in organizations; send letters to representatives and to the editor; read blog posts; read and post in social media such as Facebook and Twitter; protest, run for office, and more” (p. 75). Interestingly, giving campaign contributions or lobbying is not listed as an effective action in exercising one’s political voice. By not recognizing the political power of campaign contributions and lobbying, Perrin neglects one of the most effective means citizens have to exercise their voice in American democracy and thereby further conceals the extent to which the corporation and elites today increasingly use this political right to augment their power to the detriment of citizens.

Even as Perrin goes to lengths to include Horkheimer and Adorno in his work, he emphasizes the Frankfurt school’s cultural theory and ignores how their cultural theory was fundamentally linked to the logic of capital (Dahms forthcoming). Perrin therefore commits an untenable act of distortion of their theory. Overall, Perrin recognizes that capitalism has an impact on political processes; however, he fails to consider that by ignoring the economy in his overall formulation of democratic theory, he has neglected an integral component to how actually existing democratic processes occur in American society in 21st century political life.

Perrin’s analysis represents the form that ideology assumes today. He describes how democracy is supposed to work, as a culturally-collective system that transforms the preferences of people into public policy. However, by not accounting for the interconnectedness of the political and the economic, Perrin’s understanding of American democracy is what Lois McNay (2014) would call “socially weightless.” Perrin proposes the validity of a theory of American democracy that is so far removed from the logic of actually existing democratic processes that ultimately, his theory fails to provide any meaningful insight into how American democracy actually functions.

Perrin is not the only mainstream sociological theorist with a problematic understanding of actually existing democratic processes. In her book Can Democracy Be Saved?, della Porta (2013) presupposes that democracy is experiencing a legitimation crisis and therefore needs to be saved. Della Porta is not suggesting that democracy, in general, is in crisis. Rather she is referring to a specific version of liberal democracy that she posits has become undemocratic and less responsive to the people’s will. The global social movements, such as Occupy to the protestors against austerity all over Europe, that seek to integrate participatory and deliberative forms of democracy into the liberal democratic system are challenging this democratic deficit, according to della Porta.

Della Porta contends that since the turn of the millennium, the core tenets of a legitimate and representative liberal democracy have been corrupted by neoliberal globalization, which has produced a decline in the welfare state and a subsequent shift to markets as the legitimate distributor of resources, and also a shift of power from political parties to the executive, and finally a shift of power from the nation-state to undemocratic international government organizations. Della Porta suggests that these changes in modern societies have challenged the legitimate, liberal model of democracy and transformed it into a “neoliberal conception of democracy, based upon an elitist vision of electoral participation for the mass of citizens and free lobbying for strong interests, along with low levels of state intervention” (p. 24). The crisis of democracy results as (neo)liberal democracy increasingly subverts the peoples’ will to be represented in government.

While della Porta’s treatment of the economy and global relations between states, international government organizations and markets constitutes a significant advance from Perrin’s cultural and national analysis of democracy, della Porta’s treatment of democracy falls into a similar set of traps as Perrin.

Della Porta perceives the undemocratic features of neoliberal globalization and details participatory and deliberative modes of governance that seek to re-integrate people into the political process, however, she cannot account for the concrete mechanisms that would be needed for citizens to realize a more participatory and deliberative democratic system in the face of the ruthless and relentless neoliberalism. Who are these people who are theorized to save democracy? The core problem of mainstream sociological democratic theory is that its theorization of the people is completely devoid of any connection to how the people actually learn and acquire the skills necessary to understand and advance a substantive form of participatory democracy. It is merely assumed rather than critically evaluated that people acquire the skills and abilities necessary for a substantive democracy through various processes, experiences, and institutions of American life.

The persistence of mainstream sociological democratic theory to acknowledge, while simultaneously ignore, concrete socio-historical circumstances, in favor of a normative and ideological theory of democracy, is at the heart of the contradiction in mainstream sociological democratic theory. If actually existing democratic processes in the United States increasingly conform to the model of the “democratic method” as Schumpeter and later rational choice theorists have developed it, then American citizens are being socialized to satisfy a particular version of ‘the people.’ According to the democratic method, ‘the people’ are theorized to be a passive electorate that seeks to maximize their self-interest by voting for political parties that are perceived to be commensurate with their interests. This is a passive and demobilized citizenry, and it has increasingly become the reality of democratic life for a majority of Americans. For example, the national turnout for the 2014-midterm elections was 36.3 percent of Americans—the lowest turnout in 72 years (Alter 2014). The reality of the American people stands in stark contrast to the version of ‘the people’ posited by mainstream sociological democratic theorists. In their theories, ‘the people’ are assumed to be active agents who have in interest in not simply electing politicians, but in participating and deliberating to create public policy themselves that protect public interests.

The model of ‘the people,’ advocated by mainstream sociological democratic theorists, contradicts the reality of ‘the people’ that exists in actually existing American democracy.[pullquote]The model of ‘the people,’ advocated by mainstream sociological democratic theorists, contradicts the reality of ‘the people’ that exists in actually existing American democracy.[/pullquote] The implication is that the solution to the crisis of liberal democracy, which for della Porta is simply to supplement liberal democracy with more participatory and deliberative forms in a context of high-quality communication that empowers citizens, is fundamentally flawed. An empirical example derived from the United States in November of 2009 illustrates how the solution strategy of mainstream sociologists functions to empower not people, but capital and corporations. At this time, a random sample of three hundred Michigan residents convened in Lansing to participate in a deliberative democratic forum that sought to develop a solution strategy to address the state’s impending fiscal crisis. Organized by Stanford professor James Fishkin and his Center for Deliberative Democracy, the three-day deliberative democratic forum established, as much as possible, the conditions to facilitate rational deliberation among citizens across the political spectrum, in a mock ideal speech situation (Center for Deliberative Democracy 2010).

The deliberative democratic experiment resulted in increasing popular support for raising taxes on themselves, through the sales and income taxes, and cutting the business tax for corporations (Center for Deliberative Democracy 2010). In effect, deliberative democracy, which has been endorsed for its promise to empower the public to realize their interests, has resulted in citizens taking on the burden of the state’s fiscal crisis and allowing corporations to exact more and more profits in the process. This outcome, more or less, resembles the neoliberal economic tool of austerity where citizens shoulder the burden of fiscal adjustment while the interests of capital are protected. In the United States, the people not only vote for representatives who implement austerity, which has happened on both a federal and state level, but also actively desire austerity, and in this example, will implement it themselves if given the option.

Theorizing Capital at the Center of Democratic Processes

Mainstream sociological democratic theory is unable to reflect on its immersion in time in space, and its associated ideological mode of theorizing. Furthermore, it rejects the need to reflect on the nature of reality in general and of concrete challenges in particular because reflection would impede the employment of normatively-inspired strategies for democratic rejuvenation. To put it simply, if mainstream sociological democratic theory actually took seriously the implications of concrete socio-historical circumstances, their normatively-inspired democratic theory of having ‘the people,’ as they currently exist, save democracy would have to be fundamentally revised if not all-together abandoned. However, Dahms (2008) situates sociology as the discipline theorized to be oriented to studying specifically what impact concrete socio-historical circumstances have on the development of theory and empirical possibilities. Thus, sociology, in its non-mainstream variants, is actually well positioned to confront the discrepancy between idealized projects of democracy and the actuality of modern society. Furthermore, sociology is positioned to discern the forces in society that compel people to act in particular ways in different contexts.

A critical sociology of democracy could satisfy the requirements needed to adequately apprehend actually existing democratic processes in American society.

Overall, it is possible to suggest that actually existing democracy in American society has never meant to realize the collective popular will. Following Postone’s (1993) suggestion that social theorists must grasp “the constraints to democratic self-determination that are imposed by the abstract form of domination rooted in the quasi-objective, totalizing, historically dynamic form of social mediation that constitutes capitalism” (p. 393). It may be possible to take this statement further and posit that capital is the subject of democratic society, not the people as traditionally conceived. Such a process can be traced through the continued evolution of the corporation as a legally protected ‘individual’ whose massive capital reserves and employment of an army of lobbyists allow the corporation to be the supreme political actor in what is an increasingly incorporated American state. In effect, American democracy, as it exists, cannot realize the will of the people, as commonly theorized by mainstream sociological democratic theory, but instead, actually existing democracy has contributed to the abolition of the people as a social actor able to protect its interests in the democratic process.

References

Alter, Charlotte. 2014. “Voter Turnout in Midterm Elections Hits 72-Year Low.” Time, November 10. Retrieved April 13, 2015 (https://time.com/3576090/midterm-elections-turnout-world-war-two).

Cairns, James and Alan Sears. 2012. The Democratic Imagination: Envisioning Popular Power in the 21st Century. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Center for Deliberative Democracy. 2010. “By the People: Hard Times and Hard Choices.” Retrieved April 11, 2015 (https://cdd.stanford.edu/2010/final-report-by-the-people-hard-times-hard-choices-michigan-residents-deliberate).

Dahms, Harry F. 2008. “How Social Science is Impossible Without Critical Theory: The Immersion of Mainstream Approaches in Time and Space” in No Social Science Without Critical Theory (Current Perspectives in Social Theory) 26:3-61.

Dahms, Harry F. Forthcoming. “Which Capital, Which Marx? Basic Income between Mainstream Economics, Critical Theory, and the Logic of Capital.” Basic Income Studies.

Della Porta, Donatella. 2014. Can Democracy Be Saved? Malden, MA: Polity Press.

Habermas, Jürgen. 1962. Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Horkheimer, Max. [1937] 1975. “Traditional and Critical Theory.” Pp.188-243 in Critical Theory. New York: Continuum.

McNay, Lois. 2014. The Misguided Search for the Political. Malden, MA: Polity Press.

Perrin, Andrew J. 2014. American Democracy. Malden, MA: Polity Press.

Polletta, Francesca. 2013. “Participatory Democracy in the New Millennium” Contemporary Sociology: A Journal of Reviews 42 (1): 40-50.

Postone, Moishe. 1993. Time, Labor, and Social Domination: A Reinterpretation of Marx’s Critical Theory. Cambridge University Press: New York, NY.

Schumpeter. Joseph A. 1942. Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy. New York: Harper.