On Ken Kelman and His Theory of Cinema

The playwright and film theorist, Ken Kelman, was a contributor to Logos. His longtime friend, P. Adams Sitney, has prepared an edited collection of Kelman’s writings and unpublished lectures, which will be released by Anthology Film Archives. In memory of Kelman, below is Sitney’s introduction to the forthcoming collection. We are also publishing an excerpt from Kelman’s lectures. We have selected his lecture on Kenneth Anger, Isidore Isou, and Christopher Maclaine in honor of Kenneth’s Anger’s passing.

Ken Kelman died in late spring 2017. At the time he was still writing plays but he probably had not written on cinema for at least ten years. In fact, as far as I know, the only new film he had seen in the 21st Century was Jerome Hiler’s Words of Mercury at the Whitney Museum of American Art in March 2012. I know that only because I urged him to attend the screening with me. It was the last time I saw him, although we spoke on the telephone a few times after that.

Kelman was a hoarder. His apartment was overflowing with Tibetan art, and boxes of manuscripts of plays, the few unpublished novels he wrote, lots of prose, perhaps recordings of his lectures, and probably even gold coins.

We met in 1960 or perhaps 1959 in New Haven, when I was attending highschool and he was at the Yale Drama School studying playwriting under John Gassner. I had founded The New Haven Film Society in order to see classic films, mostly silent. In that period before videotapes, cassettes, or dvds it was nearly impossible to see such film outside of New York City (and even there it was supremely difficult). The Yale Film Society showed old films in their weekly screenings, but never silent ones. They hardly deviated from what was then the dominant taste of students: every year they showed Casablanca and From Here to Eternity.

Kelman was a regular patron of the New Haven Film Society. He was very easily recognizable. He stood out, perpetually wearing a dark trench-coat, walking with the slightest stoop, apparently oblivious to everything around him. When I would encounter him on the streets near the university, I always walked and talked with him. There was no way to get in touch with him otherwise. I must have assumed he was gay, because he always came to the film society accompanied by a painter from the Yale Art School whose mannerisms suggested homosexuality. I was wrong. Kelman was a heterosexual, celibate as long as I knew him except for two very brief affairs with young women. He had been at the Harvard Law School and dropped out, and even in the army — from which he was given a general discharge as “untrainable.”

He knew more about cinema than anyone I had met at that time. From him I learned about the work of Robert Bresson and Carl Dreyer’s sound films. (I had already made a trip to New York to see La passion de Jeanne d’Arc when the New Yorker theater gave a rare, one-night screening of it.) He taught me to appreciate Hitchcock’s Vertigo and the charisma of Louise Brooks, but I could never share his later enthusiasm for such soft-core cult films as Olga’s House of Shame (1964). In turn, I persuaded him of the glories of the American avant-garde cinema.

Kelman wrote very quickly and beautifully. At the New Haven Film Society, I had started a mimeographed journal, Filmwise. It grew out of the notes we handed out to the audience. The first issue as a full-fledged journal was completely devoted to the work of Stan Brakhage. After that each issue was centered on one or two filmmakers: Deren, Markopoulos, Maas and Menken. I asked Kelman if he might write something on Ritual in Transfigured Time for the second issue. After projecting the film for him a half-dozen or so times, he quickly wrote a brilliant essay, “Widow into Bride.” He obliged again for the Maas-Menken issue (our last).

In the fall of 1963 I took a leave from college to prepare the first International Exposition of the New American Cinema to tour European cities. I was living in New York, assisting Jonas Mekas in editing Film Culture. Kelman attended screenings with me several days each week. His remarkable insights and lighting speed of writing was a great asset to us. Just one day after the first screenings of Markopoulos’s Twice A Man, Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures, and Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising, Kelman delivered finished texts to the Film Culture office. He also wrote most of the accolades for the Film Culture annual awards in the late Sixties and early Seventies.

He was wonderfully articulate but weird. In New Haven, if I wanted to stop in a luncheonette for coffee or a burger, he would eat or drink nothing. He said he was trying to live on an exclusive diet of Kellogg’s Special K cereal, so that after leaving the Drama School he could live cheaply in New York City without working, or working only minimally. In actuality, he moved into his parents’ apartment, outlived both of them, and died there some fifty years later. The only regular job I knew him to take was a year teaching film history at Bard College (1971-1972, I think), to replace me when I resigned.

Kelman was notoriously frugal, a comical skinflint. To get him to accept dinner invitations in my home, I had to provide him with two bus tokens for his trips crosstown from his parents’ apartment of East 834d St. to mine, then on West 88th. At the same time, he was stupendously generous. If one asked to borrow thousands of dollars from him, would groan first, then bring the cash the next day. He never asked for a receipt. Nor did he mention the loan – sometimes for years –before it was repaid. I suspect several such debts went unhonored when he died.

When he did come to dinner, at my house or that of the architect Raimund Abraham, or less frequently at Jonas Mekas’s loft, he carried an astonishing array of pills that he swallowed before eating. He would never eat anything hot, just has he would never touch a person, even to shake hands. His familiarity with changing health fads was impressive; he subscribed to several. When Daniel Pinkwater (to whom I introduced Kelman fifty years ago: they became fast friends) informed me of his death, he attributed it to malnutrition. Apparently, he believed his intake of pills was all he needed.

He saw films at the Museum of Modern Art, the Filmmakers’ Cinematheque, and at private screenings when he was invited, but rarely, if ever, in conventional theaters, where he would have to purchase a ticket. He did watch old movies on television when they followed a basketball game. That was his preferred sport, but he loved games and puzzles of all sorts. To play “Scrabble” with him would have been a massive humiliation, if it were not so amusing to see how he accumulated astronomical scores, using up all of his letters several times in each game, and rarely failing to place a “q” or an “x” on the triple score square. The only time I ever saw him display intense emotion occurred when he was furious over what he took to be a violation of the rules of “Monopoly.”

He did crossword puzzles faster than I could write, bragging that he could do the Sunday New York Times crossword entirely between any two stops on the Lexington IRT subway. He even splurged to enter a national crossword puzzle contest, convinced he would win the big financial prize, only to be frustrated when he learned that he alone of the top twenty contestants wasn’t a professional crossword editor or author. Soon after I met him, he had been just as sure he would garnish a fortune from the “Famous Faces” contest of one of the New York tabloid newspapers. He was forever entering such competitions, never winning them.

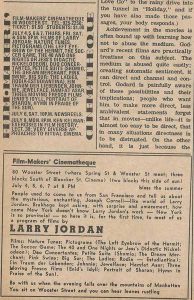

All his adult life Kelman was primarily a dramatist. After he left The Yale Drama School he would write a play a year; longhand first, then type it out. In his later years he wrote plays less frequently. His enthusiasm was always unbounded for his most recent work. I believe he was convinced he was the greastest living playwright. In 1968, the year of his lecture series, “Exercises in Film History,” at the Film-Makers Cinematheque on 80 Wooster St., he also acted in the first of Richard Foreman’s Ontological-Hysteric Theater productions, “Angelface.” Foreman, who had been at the Yale Drama School with Kelman, also used the Film-Makers Cinematheque space to launch his theater. He was the only American contemporary in the theater I ever heard him praise.

Near his death, Kelman felt his fantasy of a Broadway production was within reach: his father had bequeathed a couple of rundown apartment buildings on Long Island to him and his sister; she was negotiating their sale the last time we spoke, some months before his sudden death. With his share of the sale, he planned to mount a production of his play, Four Sisters, on Broadway. He was not concerned that it might close after a night or two: for him, the expense of two or three million dollars would be worth it.

In recent years, I often received inquiries from people who did not know Kelman about why he was on the selection committee of the “Essential Cinema” for Anthology Film Archives when it began in 1970. Although he ceased going to films and wrote nothing about cinema in the decades prior to his demise, in 1968 he was a prominent figure at the Filmmakers Cinematheque. Jonas Mekas, its director, asked him to offer a series of lectures on the history of cinema. They agreed upon a full year’s sequence—fifty-two Thursday night screenings followed by an analytical and historical lecture every Monday evening, to be entitled “Exercises in Film History.” Consequently, when the selection committee of Anthology Film Archives was formed two years later, Kelman was the best informed and most articulate film historian of the group. Already, at that time, he identified himself as an “ex-film critic.”

The scope of his knowledge of cinema and the depth of his insight was astounding. His role at Anthology Film Archives demonstrated that, even for those who had not heard his lectures. On the Selection Committee for the “Essential Cinema” he was the most articulate and least polemical member. After fifty years, I have come to realize that he was almost always right about his inclusions and exclusions. The selection process for films to be included in the “Essential Cinema” collection had been conceived as on-going and perpetual. But a severe financial crisis terminated that process around 1972. The theater had to move, first to 80 Wooster St, the home of the former Filmmakers’ Cinematheque, and many years later, to the Courthouse at Second Avenue and Second Street. Likewise, the published anthology of essays on films in that collection, The Essential Cinema, was intended to be issued annually. That too had to be terminated when the promised funding was withdrawn. It was no accident that the essays by Kelman dominated that initial volume; he wrote on von Stroheim’s Greed, Buñuel first three films, all four films of Jean Vigo, Riefenstahl’s The Triumph of the Will, Bresson’s Pickpocket, Levitt, Loeb and Agee’s In the Street, Brakhage’s Anticipation of the Night, and Bruce Conner’s Report. Those filmmakers, and most of those films, had been among those screened (or were initially scheduled to be screened) in his “Exercises in Film History.”

Unfortunately, I could not hear most of the lectures he gave at the Filmmakers Cinematheque. I had left for Europe in charge of the Third International Exhibition of the New American Cinema the day after I graduated from Yale, in June of that year. I did not return until late July, 1968 just before the New York City licensing office closed down the 80 Wooster St. theater. Jonas Mekas arranged to move Kelman’s lectures, and some other screenings, to the Washington Square Methodist Church. When that venue ceased to be available, the series was permanently suspended. I can vividly recall attending one lecture only [no. 40] – On Herbert Vesely’s Nicht Mehr Fliehen and Peter Kubelka’s Mosaik im Vertrauen. But my voice during the question period at the end of other lectures that summer proves that I attended most of those he gave once I returned to the United States. After lecture 40, I made a trip to Colorado and California. Yet by then the sequence was broken, and several lectures cancelled. There were no more advertisements for the series in the Village Voice after September 9, 1968 [lecture 39]. I believe lecture 40 was held, illegally in the building at 80 Wooster St. It was probably the last.

I have transcribed and included all the lectures that were saved on tape at Anthology Film Archives. I was surprised to find that many of them were repetitions of lectures I missed, restaged just for me. Since those were overwhelmingly Kelman’s talks on avantgarde films, I must have selected which talks, or parts of talks, he was to repeat. My garrulous questions and interventions on recordings of those lectures embarrass me. Yet they also demonstrate my thinking, and the importance of Kelman as an interlocutor, during the early stages of the formation of my Visionary Film. In fact, they remind me that Kelman was the primary influence on the historical schemata of that book. As I wrote it, I was constantly arguing with him in my mind or confirming his insights.

The survival of a few audio tapes from the start of the series and from the end, complete with questions from the audience, suggest that more of them may have been recorded. The missing tapes might have been in Kelman’s apartment when he died. All my efforts to contact his sister about the fate of his papers and possessions has failed, despite repeated phone messages and letters sent to her over three years. Kelman told me, repeatedly in the early 70s, that a woman [probably Joanna Gunderson of Red Dust Press] who attended some or all of the lectures wanted to published them. The few professional transcripts that remained in the files of Anthology Film Archives may have been the only ones she actually commissioned, but I find that unlikely. It is certain that Kelman never got around to editing them. Perhaps the publishing project fell through before he had a chance to start the labor. There is no mention of Kelman or of the lectures in her archives at the University of Indiana.

Kelman always lectured without a prepared text, depending on a fresh screening of the film to trigger his ideas. He was brutally honest about his ignorance of foreign languages, and repeatedly acknowledged aspects of the films he did not comprehend. Yet, he was convinced that in the act of discussing them he would discover their fundamental coherences. Thus, questions from the audience about specific images elicited new interpretations as often as confessions of bafflement. In lecturing he was exhibiting acts of discovery and demonstrating the workings of his acute sensibility. Among the impressive aspects of that sensibility was how he could situate all the films he showed in an historical tradition. He distinguished covert influences and formal allegiances between films with great conviction. Both before giving “Exercises in Film History” and after it he wrote synoptic aesthetic speculations on the history of cinema: “Classic Plastics and Total Techtonics” and “Cinema as Poetry” were among the most important of these in the early period; and “Animal Cinema” and “Megafilm and Metafilm” afterwards. Perhaps, even more startling was his ability to articulate convincingly the bases of those linkages. Who but Kelman would have noticed the affinity of Kubelka’s Mosaik im Vetrauen to Ruttmann’s Berlin? or Isou’s Traité de bave et d’éternité to Cocteau’s Le sang d’un poëte?

An evolving theory of the essence of cinema subtends all of his speculations on film history. Its most sophisticated articulation can be found in “Animal Cinema” perhaps his last writing on film. The static images of the individual frames – often of people no longer living — are “raised from the dead” by the rapidly flickering light of the projector. The concept of “Life” resonates throughout his writings on film. I do not know if he ever read all the way through Siegfried Kracauer’s A Theory of Film [1960]. I am convinced he perused it, at least. To a remarkable degree he shared its thesis that the primary function of cinema has been the representation of reality. In this respect, Kracauer leaned heavily on Georg Simmel’s Lebensphilosophie. I am equally convinced Kelman knew nothing of Simmel. He didn’t read philosophy, as far as I could tell. In fact, I believe he did most of his serious reading before I met him. Melville and Büchner remained his primary touchstones his whole life. He knew Greek tragedy and Shakespeare thoroughly, and I recall him extolling Tolstoy as a dramatist. But the only book I heard him praise while he was reading it was Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past. After consuming the first two volumes with enormous enthusiasm, he bogged down in Guermantes Way. He never got further in it.

Apparently, he came by his affinity to Kracauer from his intense scrutiny of most of the same films that the German-American social theorist studied, rather than stimulated by Kracauer’s own insights. Yet the differences of their orientations are more significant than their over-lappings. Kelman’s passion for cinema was tied to his antirational and pessimistic, or rather tragical, view of existence. The realism he continually noted in the essence of cinema was always “magical.” “Life” revealed itself in tis illusions. Eschewing the sociological perspective that made Kracauer apprehensive of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and horrified by The Triumph of the Will, Kelman praised the former as a masterpiece of cinematic subjectivity, and the latter as the cinema’s ultimate “transfiguration” of matter into spirit. The spectre of death is explicit in the former, and implicit, but even more palpable in the latter through the historical fate it helped set in motion.

Kelman came to cinema with the tragic conviction that Life is most vivid (or in his terms, “intense”) in the face of Death. A year or so before embarking on “Exercises in Film History,” he sent a letter to the actress Louise Brooks [Feb 12, 1966], seeking material for a novel he had begun to be called The Autobiography of Death: Fantasia on Louise Brooks or Meditation on Louis Brooks. In that letter he confessed that after re-seeing one of her silent films: “… the beauties of the past deluged me. I was obsessed with time, mortality, change.”

After the 1989 production of his play Dead Still, he composed a polemical abecedarium [unpublished] about his theater. Under “L” we find:

LIFE 1: I do not practice animation art. The so-called life (characters) of most drama is cartoons. No matter how lifelike, complex, humanly interesting, they are precisely animated. If someone on the stage just yells at us, we react with utmost intensity. It is certainly felt as life, though we know nothing of the shouter’s internal process. Why must we be aware of all the machinery at work? Is it so exquisite? So credible? The shout is crude life, it lacks the complexity and elaboration possible in a nicely detailed cartoon. I prefer it, not on the grounds of verisimilitude but of veracity.

LIFE 2: The wages of life is death. The price is right.

(More than anyone else I’ve ever known, Kelman would have profoundly appreciated the irony of my probing his concept of Life, after he died.)

The bias toward Realism in the “Exercises in Film History” and in his other writings and lectures on film is merely apparent, and superficial. Kelman always extolled the cinema for its ways of representing “Life.” The innovations in technique and perspective that he repeatedly made the center of his arguments were always methods of intensifying the Life he recognized in the films he discussed, fantasies as well as documentaries, avant-garde film poems as well as naturalist narratives. Even when he erred in his interpretations – as I believe he did in his discussion of Menilmontant – his keen observation of the dimensions of Life the filmmaker sought to capture made his analyses invaluable. The “Life” Kelman found at the cores of great cinema was a matter of the infusion of Spirit into the “dead’ material of film frames. He charted the variations on Spirit as they were manifested in the films he loved: as breath, wind, inspiration. Yahweh, Frankenstein, and Jesus were central emblems of the film-maker for him.

Yet he subscribed to no religion. His family was Jewish, but not practicing. Once he told me he was not even circumcised, and that his father wasn’t either. When I asked how this came about, since it was virtually unheard of among Jews of his generation not to circumcise boys; he told me he didn’t know and that was not the sort of thing one could ask about in his family. In the Sixties he spoke frequently of the enthusiasm for the Christian ideas — Transfiguration, Resurrection, Pre-Ordained Fate – he had acquired from his reading of Tolstoy and the New Testament, and most of all, I suppose, from the films of Dreyer and Bresson. He also admitted being impressed by the claim of the Indian spiritual leader Meher Baba [1894-1969] that he was God or the Avatar. In later, years he seldom spoke of Christianity, but of Buddhism, especially in its Tibetan variety. He amassed a large and valuable collection of Tibetan art and ritual objects in his last decades.

Sometime after the founding of Anthology Film Archives, probably in the 1970s, Kelman gave at least two talks based on films in the Essential Cinema collection. The earlier of the two was on Carl Th. Dreyer’s Gertrud, the other he called “Megafilm/Metafilm:” it was, in all likelihood, a distillation of the “Exercises in Film History.” There is also a You-Tube recording of a lecture he gave on Ordet and Gertrud at the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh. Running through all of his lectures there is an appreciation of the insight of the great filmmakers into hitherto unexplored, or under-explored, potentials latent in the transfigural, life-giving art form.

The enormous value of these lectures derives from five aspects of Kelman’s expositions: the clarity with which he selects and analyzes significant details, the originality of his insights (born of a nearly total indifference to previous critical and theoretical literature), his implicit view of cinema as the culmination of an ineluctable human aspiration to reproduce the image of Life and to conquer Death, his insistence on uniting realistic and magical tendencies (or rather, that the illusion of reality is the highest achievement of magic), and the magisterial authority with which he isolates the individual achievement of each film artist in appreciating and molding what he imagines that artist understands to be an essential power of cinema.

P. Adams Sitney wrote Visionary Film; Modernist Montage; Vital Crises in Italian Cinema; Eyes Upside Down; The Cinema of Poetry; Marvelous Names; Brakhage, Straub-Huillet, and Deleuze; and Incongruous Pairings [the last two still unpublished]; he edited five books in addition to Kelman’s lectures and writings. He served time – half a century –in academia, teaching at NYU, Cooper Union, Bard College, The School of Visual Arts, and at Princeton University. He has been retired for eight years.