The War in Ukraine and Putin’s Vlast: a sociological perspective

The true causes of the war in Ukraine are part of a larger picture of social transformation throughout Eastern Europe. To see it in its entirety, we need a science-based understanding of the nature of Putin’s rule with some help from sociology – not the kind that is reduced to opinion polls, but the sociology that analyzes the cultures that make a society, i.e. specific social groups and their values.

State Capture and Group Culture

There is consensus among Russian opposition politicians, as well as social scientists studying Russia, that the country’s viability and prosperity are linked to a transition to freedom and democracy. This transition began in the 1990s but was interrupted in the 2000s by a state capture by a specific sociocultural group. Why is it not just a social group characterized by income or status, but also a cultural group? This is because it is based on a certain way of life, beliefs, values, and ways of achieving group goals. In the case under consideration, these parameters can be seen as elements of an atavistic, archaic and traditionalist culture that contradict the modern structure of society and parasitize it.

In the very first years after Vladimir Putin came to power, it became obvious that the state-capturing sociocultural group he headed had managed to combine the practices of organized crime and state law enforcement, including the government’s monopoly on violence. The resulting system can be defined as predatory and patrimonial.[1] The latter means that Putin’s group is guided by the value of the unlimited power of the “pater,” the head of the family. In the framework of modern society, this implies the parasitic role of simplified, traditionalist mechanisms of artificial kinship, in other words, mafia.

The task of the mafia state that has developed in Russia has been to establish a father figure, head of the family, the cultural center for the “brothers” (bratki),[2] little knights, as the father of the people, whose rule should not be limited by democratic constitutional norms. Simplifying, we can apply the Russian political scientist Grigory Golosov’s characterization of Putin’s power as a personalist autocracy.[3]

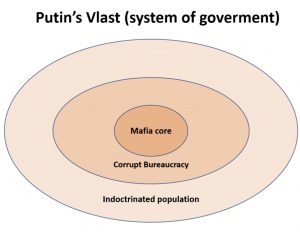

As a result, Russia has developed a system of state power (vlast) that can be described as mafia core that co-opts corrupt bureaucracy and pursues the goal of indoctrinating the general population through mass deception in order to reconcile them with the state capture by the mafia and instill the idea of “stability”. It can be visualized as follows.

Launching the democratic transition

Not only according to Russian oppositionists, but also from the point of view of objectivist social science, the precondition for a democratic transition in Russia is political demise of Vladimir Putin as the basis of Russian personalist Vlast, or government system. This also means that moving him to any other position within the existing power system—be it a Russian version of Kazakhstan’s Yelbasy[4], prime minister or head of parliament—is not an acceptable option for him. There can be no “successor” for Putin, as this destroys the very foundations of the personalist mafia core of the state to which its other parts—from the corrupt bureaucracy to the mechanism of mass indoctrination—are attached.

But what will happen after Putin? The initial phase of almost any scenario of democratic transition, that is, the period immediately after his political disappearance, will include the need for the Russian leadership to respond to the obvious primary expectations of Russians, those of peace and some economic prosperity. A government of “Patruchevs”[5] will not have the necessary resources to continue Putin’s foreign policy. Even such a government would have to end the war in Ukraine, which is entirely Putin’s enterprise. Even Patrushevs, not to mention Sobyanins-Mishustins,[6] will have to present a program of economic improvement to the people of Russia.

Putin’s three scenarios of the war

However, in order to figure out the structure of democratic transition, one has to “get inside the criminal mind,” i.e., to make sense of Putin’s main war scenarios. Given the cultural determinants of Putin’s mafia rule, there can only be three such scenarios—A, B and C. Once started, Putin’s war will go on until the end—that is, until Putin ceases to function as the mafia capo di tutti capi. The only question is the form of conducting the war.

The failures of Scenario A (blitzkrieg, offensive on Kiev in the first weeks of the war) and Scenario B (protracted fighting in eastern Ukraine, things like the fixation on Bakhmut) lead to the relocation of Putin’s “endless” war to the territory of Russia itself, i.e. to Scenario C. At the same time, it is important to understand the following:

– Ukraine’s victory is a necessary but not sufficient condition for Putin’s demise. It should be understood that at this moment the resources of Putin’s vlast significantly exceed the costs of its admitting defeat on the battlefield and turning NATO into the main enemy “operating on Russian territory”.

– Putin’s demise is sufficient, but NOT a necessary condition for Ukraine’s victory. That is, Ukraine can cope with the aggression even if Putin is still in charge of Russia, although his demise guarantees speedy victory for Ukraine.

Unfolding with defeat in Ukraine, but with Putin still in power, Scenario C means a civil war on Russian territory in one form or another. It is important to understand that it is not civil war in the classical sense of “brother against brother” or a war between regions of a large disintegrating country. Its nature lies in the struggle between a modernist (based on political and consumer choice) civil society and a traditionalist (archaic, patrimonial) system of mafia state. That is, Putin’s Scenario C will represent the last, and the second, along with the period of 1918-22, acute phase of the Civil War that unfolded in the post-imperial Eastern European space more than a hundred years ago.

Scenario C

Speaking about the only alternative to democratic transition, the outcome of Scenario C is possible as turning Russia into a “besieged fortress” only under the condition of Putin’s long-term political survival and finding a comprehensive and, at the same time, acceptable to the free world way of its protection by China. More likely are other outcomes of Scenario C leading to Putin’s demise and Russia’s subsequent, rather quick setting on the path of democratic transition.

Given the high probability that authoritarian rule in Russia will continue for some time since no occupation by foreign powers is at the moment envisaged, the speed and quality of the initial phase of democratic transition will depend on three main factors:

- resources of the Russian system of vlast, after it loses Putin as its core;

- the degree and character of the pressure on the system from the external environment (the free world);

- the degree and character of the pressure on the system from the internal environment (civil society in Russia and in the diaspora).

Here is an important reservation:

- – Establishment of totalitarianism in Russia is impossible due to the lack of mass ideology and system of ruling party management; this is impossible even if Putin remains in power, so the “North Korea option” can be ruled out.

- – Immediate transition to a personalist system of vlast (government) headed by some Putin’s successor is impossible, as it requires a very long time to build it.

Not to give in to impression management

For both the Russian movement of resistance to Putinism and, more importantly, for the leaders of the free world, it is crucial to understand that Putin’s behavior is that of a specific cultural agent of the mafia type. We are facing here a “secondary deviant” who does not simply practice deviant behavior as an elementary social offense, but who has interiorized the role of a criminal and uses it as his main sociocultural capital.[7] For a secondary deviant, the key social technology is impression management,[8] which in Putin’s case axiomatically includes lying, bluffing, blackmailing, and use of euphemisms such as “foreign agent” instead of “enemy of the people,” “special military operation” instead of “war,” and so on. Putin’s war in Ukraine in this context is a euphemism for war against his own people.

It is crucial for analyzing Putin’s rule and Putin’s war to understand that, being guided by the desire to indefinitely postpone his political demise in Russia, he launched this war in order to cope with something that is unbearable for his vlast. What is unbearable is the influence on the Russians of the positive example of democratic and economic development of the most important neighbor. For Putin, it is the prospect of Ukraine’s sociocultural modern consumerist success that decides everything here, not the geopolitics of Ukraine’s NATO membership. Within the framework of his terrorist rationality, Putin is by no means ignorant of the insignificance of the threat from NATO, but at the same time he is extremely anxious to sell this threat to his domain as an element of the general mafia impression management.

Therefore, the task of scientific enlightenment of both ordinary Russians and western politicians is to confront Kremlin’s justification of the war in Ukraine as being waged between Russia and NATO or for the purpose of reconquest and development of certain historical lands. To counter the inflated image of Putin as someone who is “great and terrible”, a preeminent geostrategist of our time, one needs to employ simple explanations of his aggression as not at all imperialist or colonialist, the idea that popular interpreters like Timothy Snyder are trying to sell, thus playing into Putin’s hands. For all its destructive character—and because of it—the war has for Putin and his mafia culture primarily the symbolic function of terrorizing primarily the Russian population, i.e., his own mafia domain, by demonstrating what Putin can do to them if the internal threat to his vlast becomes critical. In other words, the external war for Putin is an indirect intimidation tool to be used against the Russians, a euphemistic device within the framework of impression management in order to impose martial law in Russia in a situation where its direct imposition would lead to radically strengthening the public resistance to his eternal rule.

How to strengthen the fronts

The offered perspective should strengthen all the three anti-Putin fronts—on the battlefield in Ukraine, in the political circles of the free world, and among the Russian civil society on both sides of the country’s border. The illusion of military and political “escalation,” including the imaginary threat of a tactical nuclear attack, must not be succumbed to. Putin’s opponents must exercise control over the deviant from a coercive position, which will lead to the final collapse of Putin’s Scenario B, but will also hasten the full launch of Scenario C, elements of which have already been launched in one way or another—primarily in the form of growing political repressions in Russia.

It should be made clear that talks about Putin preparing new wars against other than Ukraine neighbors after his defeat in this war are groundless, since he will not have the resources to do so even with hypothetical full financial and economic support from China. On the contrary, Putin is already allocating greater resources to fighting resistance inside Russia, the population of his own domain being his main existential threat, and is preparing to throw all his remaining forces at it after his defeat in Ukraine.

Therefore, the principal sociological recommendation here is as follows: the reasonable position of the Russian anti-Putin resistance is to realize the inevitability of a further unfolding of such a conflict inside Russia, the scale of which may surpass the scale of the war in Ukraine,[9] to accept its role in this conflict and to strengthen its modernist potential to counteract the forces of the past. What can be added to support this conclusion is that the June 2023 mutiny of Evgeniy Prigozhin, the head of the notorious Wagner mercenaries and an important actor within Putin’s mafia state, and his elimination in August only confirm the logic of Putin’s war transitioning from Scenario B to Scenario C when the chaos with which Putin has tried to manage the unfavorable situation starts to hit him back.

Sergei Erofeev, Rutgers University, USA. Before leaving the country after the Crimea annexation, he was one of the pioneers of cultural sociology and global education in post-Soviet Russia. He served as a Vice President of the Higher School of Economics Moscow, the Dean of International Programs, the European University at Saint Petersburg, and the director of the Center for the Sociology of Culture at Kazan Federal University, Tatarstan, Russia. A cultural sociologist, scholar of political emigration and communication, he has led many large-scale international projects. Sergei is currently working on the methodology of studying “tectonic value shifts” and the culture of mafia state and Putinist terrorism.

[1] Magyar, B., Madlovics, B. (2020) The Anatomy of Post-Communist Regimes, Central European University Press.

[2] Stephenson, S. 2015 Gangs of Russia: From the Streets to the Corridors of Power, Cornell University Press.

[3] See: https://holod.media/2023/02/01/russians-against-democracy

[4] Yelbasy is the specially assigned honorary father-of-the-nation and, in fact, power exerting role assigned to the former Kazakhstan president Nursultan Nazarbayev which he performed until the riots of January 2022.

[5] Nikolai Patrushev has previously served as the director of the Federal Security Service (FSB, the KGB successor), the chief “silovik”, i.e. law enforcement agent, seen as one of the key members of Putin’s inner circle, the “hawk” of the war and internal repressions.

[6] Sergei Sobyanin and Mikhail Mishustin play the role of economic “technokrats” in Putin’s government as opposed to “siloviki”.

[7] Lemert, E. M. (1951). Primary and secondary deviation. In E. Rubington, & M. S. Weinberg (Eds.), The study of social problems: Seven perspectives (pp. 192-195). New York: Oxford University Press.

[8] Goffman, E. (1959) The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, Penguin Books.

[9] See Ilya Yashin’s interview to Der Spiegel where he says that a “bloody disappointment awaits Russia”: https://www.spiegel.de/ausland/kreml-gegner-ilja-jaschin-auf-russland-wartet-eine-blutige-ernuechterung-a-aca59dbe-04d8-44b4-b979-a96bf2b3b800