Review: Benjamin Ginsberg, The Fall of the Faculty: The Rise of the All Administrative University. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press 2013

Benjamin Ginsberg’s The Fall of the Faculty provides a compelling and accurate diagnosis of the contemporary ills plaguing the rise of the all-administrative university. Ginsberg’s analysis strongly resonates with my own experience at several different institutions (public and private) over the last ten years, as I have personally witnessed how administrators have used their positions of managerial oversight to advance their personal interests, essentially turning the university into a political bailiwick. Ginsberg’s analysis leaves one with little doubt about what the consequences of this rapid expansion of the administrative corps are: The rise of the all-administrative university has been ruinous for students, who foot steadily increasing tuition bills to keep the administrative bloat going, bad for faculty autonomy as contingent labor becomes increasingly prevalent, with the concepts of academic freedom, tenure, and shared governance devolving into relics of the past; and destructive of the public interest as educational institutions classified as not-for-profit enterprises use non-taxable endowment income and indirect cost recovery associated with grants and discoveries—and in some instances grant overhead–to facilitate the creation of organizational wealth, which unsurprisingly goes to increasing administrative salaries and perks instead of to the funding of teaching and research.

In the contemporary scene, the major goals associated with the values of a traditional liberal arts education have seemingly been sabotaged by career bureaucrats. The self-promotion and puffery associated with administrators, the psychobabble promulgated by those Ginsberg derisively labels as “deanlets” and “deanlings”—not to the mention their dutiful and mindless staffers— who carry out their tasks by deploying the rhetoric of excellence and diversity, while in reality protecting administrative interests (not to mention the waste, embezzlement, insider trading, and fraud typifying the corporate university), make a mockery of the core academic mission. Within such a situation, to paraphrase the title of Richard E. Miller’s brilliant book, it’s as if learning is really beside the point.

Ginsberg’s warnings about the rise of the all-administrative university should be taken seriously among faculty who are committed to preserving the seriousness of the educational enterprise. If the administrative apparatus continues to grow at its present rate, university professors may very well disappear themselves. Administrators have been clever in exploiting the university’s bureaucracy in advancing administrative interests while marginalizing faculty expertise, concerns, and perspectives. If administrative expansion continues at current rates, what possible hope is there for the resurrection of the faculty-controlled university?

Ginsberg uses the phrase “administrative imperialism” to describe the increasing creep of the administrative imperatives into what were once faculty-controlled domains. He notes that administration was something faculty used to do part-time, with the understanding that teaching and research were their main commitments. Now, being an administrator is a full-time job, with those who are not particularly productive faculty members flocking to become administrators. Ginsberg effectively dismisses the belief that this administrative expansion into once-faculty-controlled domains has anything to do with increased state oversight or federal government regulation of affirmative action programs and grant distribution/oversight, especially since the greatest administrative growth has occurred at private universities. Furthermore, there is simply not enough work for these administrators and their assistants to justify such a huge expansion of the administrative apparatus. Personal aggrandizement and professional advancement, rather than a commitment to the institution, faculty, and students, seemingly remain the chief administrative concerns.

With many college and university administrators using their current positions for advancement to a higher-ranked school, a continual process of jockeying and self-promotion obtains as the norm. Administrators go through the motions, mouth platitudes about how great the institution is, and grease the right palms. For example, every four or five years college and university administrators recruit faculty to commit to the process of formulating a strategic plan, which is supposedly geared toward contemplating the university’s future. Everyone seems to understand that the creation of such plans is in actuality a well-orchestrated sham, as no one really possess a good sense of what the buzzwords filling such plans (which are like so many other plans at other universities) really mean or even refer to. University officials who tout these plans have their eye on a different time horizon, i.e. their own bottom line and the advancement of their careers.

One of Ginsberg’s most damning indictments against administrators, and it’s an indictment that I completely concur with, is that that they are not particularly well qualified to occupy the positions they hold. Of course, this indictment does not apply to all administrators, but one does not have to be in a university long before learning that the mere mention of certain administrators’ names brings with it a certain amount of faculty eye-rolling and groaning. Typically, upper administration identifies the faculty members it wants to recruit into administrative leadership positions when it wants to avoid bringing in outside candidates. These faculty members are “uncontroversial” and viewed as “team players.” Being a “team player” and “uncontroversial” in this context of course means not criticizing, embarrassing, or resisting one’s superiors. This entails shutting down one’s better instincts and common sense and never (heaven forbid) acting on principle.

Because of this tendency to select those who will not rock the boat, administrators are careful to exclude faculty who might expose their incompetence and real agenda. So substantive discussion about serious issues with administrators is out of the question. Frequently, administrators view faculty who are persistent in researching issues around shared governance, as well as procedures pertaining to the functioning of the university, as very active threats to their inflated sense of authority. For example, some upper administrators are not only unfamiliar with the content of their university handbook (the supposed guarantor of student and faculty rights, as well as the place where one locates detailed procedures for the operation of the university), but do not care that they are unfamiliar with it since they rule by executive fiat. In this bizarre world, the only rule that matters is the one that serves the administration at a particular moment in time, enabling rather creative interpretations of what the handbook actually says or outright dismissals that the handbook is wrong or antiquated. Faculty members, who directly confront administrators about how muddleheaded a particular administrative decision is, will face serious consequences. Even when such confrontations are well meaning and have the best interest of the university at heart, administrators react defensively, insisting that they know best or are privy to confidential information that are beyond the comprehension skills of the faculty.

Administrators are smart enough to know that they must avoid forums where probing arguments and the presentation of convincing evidence will be required. When all ducking fails, administrators have used the charge of “harassment” against faculty and students who raise disturbing questions about problematic administrative practices such as embezzlement, fraud, and theft. As Ginsberg notes, most harassment on campus these days is of the administrative kind. If administrators were accorded as little due process as faculty, an administrator who is even accused of harassment should be promptly removed for his or her position. At the end of the day, however, administrators have a number of weapons that they can deploy to escape being held accountable for their words and actions.

It’s not difficult to figure out what all this means for the advancement of innovative leadership. For example, in the context of searches for university executive positions, search firms choose the most boring and conventional of candidates, making a point to steer away from those who appear the slightest bit edgy or controversial. . Search firms quickly identify the favored candidates by locking in on traditional credentials and experience. As Ginsberg points out, the head hunters at these firms know next to nothing about the world of higher education, being easily duped by candidates successfully spout the required lexicon of corporate buzzwords—“best practices,” “accountability,” “assessment,” and “benchmarking.”

That administrators conspire to marginalize the faculty voice, undermine tenure, and scuttle shared governance principles within their institutions is undoubtedly true. The move to increasingly rely upon contingent labor gives administrations yet another way to control the faculty. Since non-tenure-track faculty can be dismissed at a moment’s notice, administrators do not have to be bothered with the resistance of the faculty when it comes to changing the curriculum, scuttling meritorious research, or controlling once-successful programs. The administration will proceed to do what it judges best, while offering up the pretense of faculty consultation. Ginsberg describes a number of instances in which faculty senates were disbanded because they stymied administrative ambitions. Financial exigencies, as Ginsberg points out, have provided administrations with an ingenious way of undermining due process procedure for doing away with academic departments and whole programs. When all else fails, administrators can insist that an emergency situation has forced them to forego consulting with anyone on the faculty because time is of the essence.

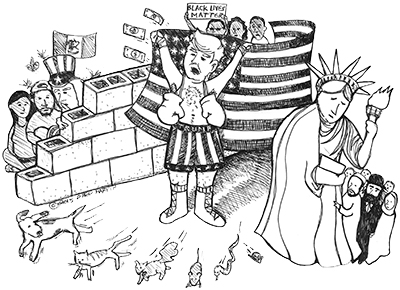

Seemingly adopting a line of critique from the cultural right, Ginsberg asserts that crafty administrators understand that they can create alliances with minority activist groups on campus by being solicitous of the multicultural agenda, posturing as supporters of these activists concerns and perspectives in exchange for these activists’ support of the administrator’s agenda. As part of this trade off, administrators look the other way when it comes to evaluating the low enrollment of ethnic studies and women and gender studies programs, preferring to keep these programs afloat rather than to appear insensitive to the multicultural agenda, which would result in the withdrawal of political support from these politically active constituencies on campus. Furthermore, administrators have effectively developed a hidden curriculum that they exclusively control to further sideline the faculty. Never mind that the courses offered in this hidden curriculum focus on life skills and various types of political indoctrination related to race, gender, and ethnicity, subjects that the deanlets and deanlings are hardly qualified to teach. Add to this, speech, civility and anti-harassment codes, which administrators use with great effectiveness to silence faculty and student critics who interfere with administrative designs. These same administrators often rely upon outside agencies and licensure groups to discipline the faculty with outside assessment measures, threatening the faculty with the school’s possible loss of accreditation. Administrators often interfere with well-running programs, attempting to change their structure to the point of ensuring their failure.

What Ginsberg describes here is a reign of administrative terror that most faculty have come to passively adopt as unbreakable. The grip of this terror is ensured by the upper administration’s, specifically the university president’s, close connections to the members of the Board of Trustees/Regents, who prefer to leave university business to administrators. Ginsberg argues that upper administrators work diligently to keep the faculty from communicating with the trustees, obviously preferring that the idyllic vision of the campus remain uppermost in the minds of these key business people and donors; faculty gripes and grievances disturb this vision. If faculty were to regularly communicate with the Board of Trustees or Board of Regents, administrators would be placed on the defensive, forced to account for bad decisions and financial missteps. Perhaps such communication from faculty members would result in Boards adopting the following recommendations from Ginsberg:

- Boards should shift spending priorities at their universities from management to teaching and research [Boards will quickly realize that it can do without administrators who are constantly meeting and retreating};

- Trustees should compare their own school’s ratio of managers and staffers per hundred students to the national mean [How is it that some large state universities get by with 7 or 8 administrative staffers per 100 students, whereas other schools require as many as 64 staffers per 100 students?];

- Boards must be wary of administrators who spout managerial jargon [Managerial theory, as Ginsberg notes, has the sole goal of imposing hierarchy on the institution. Managerial jargon simply appeases underlings, while providing the façade of consultation.]

One of Ginsberg’s recommendations is that Boards of Trustees should police themselves with respect to a strict conflict of interest rule, avoiding even the appearance of insider trading with respect to a board member providing services to the university. Here is a place where faculty members have a key role to play, especially if there is a designated spot or two on the Board for faculty members who can police conflicts of interest. While I’m skeptical that Boards of Trustees and Regents will be receptive to such positions for strong faculty representation (there are after all such positions for students), it would at least create an avenue for faculty to present their views to Trustees. Of course, some Boards already do have some faculty representation (perhaps one slot), but the jury is still out on how effective this representation is in countering administrative power.

Given Ginsberg’s cogent analysis in The Fall of the Faculty, what can actually be done to advance reform? I believe challenging the public perception of administrators, in their role as managers, is essential. As Ginsberg shows, administrators control the PR organs of the university and, in turn, the public perceptions of the administrator’s role in the university. This administrative control over public perceptions about the university’s functioning facilitates the covering up of administrative misdoing, except in the most egregious of cases when serious fraud on the part of a university president or financial officer is uncovered. Faculty have a clear role to play in establishing alternative channels for distributing information about administrative malfeasance to alumni, current students, and parents. Why rely on the media relations office to get the word out about where the university is heading when the staffers in that office have absolutely zero incentive to tell the truth about the administrative shirking, sabotaging, and stealing affecting the long-term health of the institution? Presumably, alumni do care about the reputation of the institution where they earned their degrees. Faculty should nurture relationships with key alumni, using these relationship to check and puts the brakes on administrative power. Finally, we should encourage strong faculty personalities to go into administration; these faculty possess the resolve to speak out loudly against administrative corruption. Plus, they will stand in stark relief to the sycophants the administration normally puts forward as “the faculty voice.”

It is crucial that faculty publicize administrative malfeasance within their universities. Given that there is increasing interest in the kinds of anecdotal evidence Ginsberg provides in The Fall of the Faculty about administrative abuse, especially in the wake of the 2008 financial collapse, publicizing administrative misdeeds may lead to the gathering of a critical mass of faculty, students, parents, and alumni who will be prepared to fight back against the theft of the university. Parents will certainly be interested in the kinds of abuses Ginsberg examines, since they are the ones often footing the skyrocketing price of tuition. The next time a student or parent blames escalating tuition bills on increasing faculty salaries, we should be quick to correct them. We should immediately spotlight the salaries of our university’s mid- and upper-level managers. Indeed, administrative salaries have not been subjected to the kind of scrutiny they deserve because most people do not know about them, preferring to focus on faculty indolence and self-indulgence. In brief, faculty are convenient scapegoats, absorbing the blame for the effects of administrative expansion and recklessness.

The administrative imperative seems to be: promote and increase thyself at the expense of the common good. That administrative salaries have climbed at an annual rate of 5%-10% in the midst of financial crises at so many educational institutions is obscene. Not only are administrators undermining and marginalizing the faculty, they are appropriating institutional resources for personal advancement and gain. That they are doing so by paying lip service to mantras such as “diversity,” “multiculturalism,” and “civility” is especially obscene.

The administrative imperative seemingly posits that the administration is always right, it can’t be questioned, and that it always wins due to the strength and number of its weapons. Resisting the administrative imperative requires publicly challenging administrators (as Ginsberg has done) when they seek to take over successful programs, pour millions of dollars into technological boondoggles, or implement wacky schemes that everyone warns will fail. Administrators know that faculty members are timid and are unlikely to organize to resist administrative actions. When faculty do organize and go public, administrations become defensive, occasionally backing down or admitting error. When they do face major resistance from the faculty, administrations often back down to avoid constant media attention.

In closing, I will offer perhaps the most immediate solution to the problem of administrative blight. Many of us, who are willing to take the battle to the enemy, must commit to going underground, preparing our professional profiles to do battle with administrators as administrators. I’ve often wondered what it would take to put together an administrative career in the all-administrative university. The first thing I would have to do is avoid any and all political controversy in my scholarship and public utterances, even going so far as to excise any evidence of previous strong commitments to unpalatable causes and charged statements about relevant issues. I might even go so far as to renounce these past allegiances as youthful errors. Then, I would have to dispense with any critical examinations of the academic institution. In other words, I would simply stop criticizing the institution, as well as my location within it. In the course of promoting myself as suitable administrative material, I would portray my faculty colleagues as pampered, lazy, and unaccountable, while praising my administrative superiors as visionary and committed leaders. Of course, I would quickly begin spouting the latest about “benchmarking,” “best practices,” and “accountability,” while expressing my strong desire to attend an endless stream of meetings and retreats. I would disparage tenure, academic freedom, and shared governance as irrelevancies that stand in the way of smooth managerial control. Finally, I would express interest in offering life skills courses on event planning and meditation, while imposing a shadow curriculum on the faculty and disciplining those who resisted me with appropriate civility training. I can confidently predict that my rise to deanlet status would be just around the corner.

Mathew Abraham is associate professor of English at the University of Arizona.