The Avant-Garde Film, Revisited

Shortly before his death this year, the film theoretician, P. Adams Sitney, significantly revised one of his earliest articles on avant-garde cinema and submitted it to Logos. In its first iteration, the article provided one of the first attempts to chart the currents of avant-garde cinema at a point when the movement thriving. This revised version’s tone and content is significantly different. It reflects on the movement – of which Sitney was, himself, an important part – as well as its achievements at a point when this strand of cinema has entered, at the very least, a period of decreased activity. Originally, Sitney had proposed publishing the article in multiple parts. However, given his recent passing, it made more sense to present Sitney’s article – what may have been his final piece of writing after a distinguished career – in its entirety.

– Gregory Zucker, Editor

1.

The earliest impulses toward the establishment of an independent cinema arose from a desire to temporalize pictorial strategies by Cubist, Futurist, and Dadaist painters. The very last issue of Apollinaire’s Les Soirées de Paris (1914) contained Leopold Survage’s description of his ultimately unrealized film Le Rythme Coloré. From the same period both Kandinsky and Schoenberg conceived of film projects which were never executed. The text of Survage’s “Le Rythme Coloré” has been translated in English, and the projects of Kandinsky and Schoenberg have been analyzed in Standish Lawder’s The Cubist Cinema (1975). The earliest films actually completed by major figures of the “Modern” movement seem to have been lost or destroyed soon after they were shown; only stills remain today of La Vita Futurista, a collective effort involving Marinetti, Ginna, Balla and others. The Futurist Cabaret Number 13 of Larionov and Burilik seems also to have disappeared.

Artist: Drew Martin

The graphic filmmaker repudiated the rich inheritance that film accepted from photography. The first filmmakers, the Lumiéres and their cameramen, utilized with glory the deep space and re-ceeding movement available to the camera lens, which had been ground in conformity with an idea of perspective emanating continuously from the Renaissance. The first graphic filmmakers came to cinema from painting, especially from Cubism and geometrical abstraction. They believed that they could discover the essential in cinema only after they rejected the ease with which it recorded illusory depth. This was the reason many of them turned to animation. It was one route to the flatness of the modernist canvas. Four central works of the graphic cinema in its initial stage de-serve special attention here: Rhythmus 21 (1921), Symphonie Diagonale, (1923), Le Ballet Mécanique (1924) and Anémic Cinéma (1926).

Hans Richter and Viking Eggeling worked and lived together when they made their first films. For both men, cinema seemed a natural extension of their scroll paintings. In 1920 they convinced U.F.A. to aid them with film experiments. Out of these experiments came Richter’s Rhythmus 21 and Eggeling’s Symphonie Diagonale. For many years, informed taste preferred Eggeling’s film to Richter’s; in their shared aspiration to achieve a musical construction from elementary plastic shapes. The preference may have been abetted anachronistically by the achievements of Peter Kubelka’s Arnulf Rainer (1960) and Tony Conrad’s The Flicker (1966). Eggeling’s film achieves a complexity of repetition, inversion, and variation that is lacking in Richter’s. Yet recently taste seems to have shifted; one finds critics preferring Rhythmus 21 for its frank use of purely cinematic materials—the empty screen, black and white alternation, the disappearance and reemergence of simple shapes.

Viking Eggeling, Symphonie Diagnole (1924)

The shift in taste reflects a serious change in the concept of cinematic form among avant-gardists over a fifty-year period. Briefly, one sees the birth, evolution, and decline of the musical organization of filmic time. Simultaneous to that decline is a renewed interest in the overall shape of a film. It is precisely in its elaboration of a shape that Rhythmus 21 became a prophetic film. It opens with the empty white screen. The edge moves from one side until the whole is black. That sweep is repeated from the other side; then the top and bottom edges converge on the center. Out of the alternations of full screen transformations of black and white emerges a white square which crosses the screen in various ways and dives in and out of its virtual vanishing point deep in the center. Through the multiplication of squares and the incorporation of negative images which again transform the black/white relationships, Richter gradually constructs a complicated composition reminiscent of a Mondrian. Although the image remains only briefly before the accelerated decomposition of the variations in the last moments of the film, one feels that the whole film has led up to this fleeting image. Its shape then-suggests a slow crescendo and a rapid diminuendo, affirming throughout the square of the screen and the alternation of black and white as the essentials of cinema.

In his manifesto “The Badly Trained Sensibility,” Richter reiterates and enlarges upon the position of Survage, who had written:

A static abstract form is still not expressive enough. Whether round

or pointed, oblong or square, simple or complex, it only produces

an extremely confused sensation: it is only a simple graphic notation.

Only when set in motion, undergoing change, entering into relations

with other forms, is it able to evoke a feeling.

To this general thesis Richter adds the fascinating proposition that abstract film is able to achieve “feeling” through its unique temporality; for by divesting itself of photographic objects it reorient the work of “memory.” The mind, free from associations which the sentimental cinema exploits, experiences time as feeling.

Fernando Léger’s Le Ballet Mécanique sets itself several tasks: an anatomy of cinematic rhythm, comparing regular movements within a shot to rapid montage, the intensification of awareness towards objects, including the human body as an object; and as synthetic view of choreography of ordinary things and common actions (whence the title).

The optical space of the film is made shallow as a result of concentrating on objects, by means of closeups without establishing shots, masking out portions of the picture, the placement of objects against a shallow backdrop, and unusual angles of camera placement. The editing involves loop printing (repetition of the same shot without interruption), rapid intercutting of geometric forms, inversion, rapid intercutting of two views of the same object, animation of objects into crude “dances,” and especially comparison of movements by juxtaposition.

Fernand Léger, Le Ballet Mécanique (1924)

The whole of the film evolves through a conflict between deep and shallow space, between moving and still images, in such a way that the longer rhythmic movements (the girl on the swing, the washerwoman climbing the steps over and over, the rotation of gears and pistons, the moving prismatic distortions) form a kind of visual consonance and the shorter flat images a dissonance.

An interesting example of the cinematic application of a standard cubist strategy occurs at the end of this film when Léger plays with the headline “ON A VOLE UN COLLIER DE PERLES DE 5 MILLIONS.” Clement Greenberg has described the evolution of the flattened cubist canvas:

The first, and until the advent of pasted paper, the most important device that Braque discovered for indicating and separating the surface was imitation printing, which automatically evokes a literal flatness.

When the words first appear, we tend to read them as if they were written on the screen itself, without depth. Then Léger cut back and forth between three zeros in this sequence. The central zero is seen in closeup; then a long shot shows all three. The change of scale emphasizes the virtual depth between camera and image even though the white oval on a black base has no depth in itself. Furthermore, Léger returns to the zeros to dolly to and away, making doubly explicit the sense of camera depth. He also shows the writing upside down, and in fragments, to formalize its literal message.

In 1926 Marcel Duchamp enlisted the help of Man Ray and Marc Allegret to make a film of his roto-reliefs, mechanized disks with spiral lines and printing. The resulting film, Anémic Cinéma, alternates a series of flat spirals which appear to recede or protrude from the screen when they move, with a series of puns printed spirally which appear perfectly flat as they are read. The issue of the relationship of the image to language, of which the Surrealists made much at the same time, becomes uniquely inflected. The sexual allusions in the puns tempt the viewer to read the spiral illusions as breasts, penises, vaginas, even feces. Yet this association is so deliberately tenuous that the very tendency to associate it brought into question. Here cinema itself is represented as anemic: shallow, the play of optical illusions, indeed a toy for inducing effects within a spectator’s imagination. “L’aspirant habite Javal et moi j’avais lhabite en spirale,” reads one of the disks. The je or “I” here is not that of the filmmaker or pseudonym Rrose Selavy, but an empty phoneme vainly aspiring to a reference with which it can never make contact.

While eliminating rhythm and analogy which are so important in Le Ballet Mécanique, Duchamp created a work whose radical importance did not become apparent until the late 1960’s when avant-garde filmmakers began to reconsider the relationship of images to words.

2.

These four crucial works by Eggeling, Richter, Léger, and Duchamp either repudiate or reduce to a paradoxical status the authority photography has had in maintaining the Renaissance conception of haptic space. Furthermore, they ignore the privileges of diachronic causality as a model for filmic construction. Instead, they articulate a purely cinematic temporality, called “rhythm,” which either excludes or subverts mimetic representation.

Although the spatial prejudices of the manufactured system of lenses and registration which are the givens of cinematic representation could be overcome by the techniques of animation and distortion characteristic of the graphic cinema, the temporal reconditioning of the mechanism was more problematic. The sheer successiveness with which the camera records images inscribes a linearity within the very act of cinematic recording. From the beginning, Lumiére’s cameramen realized the comic or startling potential of the simple reversibility of that succession: they cranked the projection of divers at the Baths of Diana so that they arose from the un-splashing water and flew to the diving board. As early as1915, the psychologist Hugo Munsterberg conceived of the dramatic potential in the reordering of the camera’s automatic succession:

We might use the pictures as the camera has taken them, sixteen in a second. But in reproducing them on the screen we change their order. After giving the first four pictures we go back to picture 3 ,then give 4, 5, 6, and return to 5, then 6, 7, 8, and go back to 7, and so on. Any other rhythm, of course, is equally possible. The effect is one which never occurs in nature and which could not be produced on the stage. The events for a moment go backward. A certain vibration goes through the world like the tremolo of the orchestra.

By the mid-twenties Jean Epstein was captivated by the formal possibilities of manipulating different speeds of recording. It is remarkable that despite these theoretical insights, no filmmaker made radical use of the independence of otherwise successive photograms within a shot before Peter Kubelka made Schwechater (1958), where the individual photograms of a series of simple gestures, of pouring and drinking, are organized in a rhythmical, rather than representational, manner. Until that moment the fundamental attack on the linearity of filmic time took place at the level of the shot change rather than photogramically. Jean Epstein himself was one of the most interesting figures in film history. Initially a poet, he made forty-one films between 1922 and 1948; In, La Chute de la Maison Usher (1928) he combined two Poe stories, “The Fall of the House of Usher,” and “Ligeia” to depict the darkest aspect of the artistic imagination through a Pygmalion myth in reverse, where the painting draws the life of the beloved model. No other film of this period so powerfully uses the visual representation of sound. Here the Orphic music of the artist, who plays a guitar, and the forces of nature shift continually between cause and effect, initiation and inspiration, delusion and actuality. Epstein portrays a hopelessly obsessive aesthetic vision as a wild confusion of mind and materiality through the use of differing degrees of slow motion.

Jean Epstein, Fall of the House of Usher (1928)

Slow motion becomes the vehicle through which sound effects are visualized. A considerable emphasis in Epstein’s theoretical work (he wrote seven brilliant books) is placed on the different speeds of the camera. The constitution of an object and its narrative function, he held, is dependent upon the speed at which it is filmed. The climax of Usher illustrates this principle in several ways: the intensity of the wind is visualized through the speed of rustling drapery and of waves on the lake; while the mood within the chateau is rendered by the slow turning of the pages of a book (as it is read by the owner’s guest, whose deafness is a foil to the elaborate sound imagery), or the superimposed reverberations of a guitar string as it breaks, and the superimposed hammering of coffin nails as it echoes in the artist’s mind.

In his masterful La Glace a Trois Faces (1927) Epstein demonstrated his inventiveness with narrative forms. He chose a simple story by Paul Moran as his vehicle; in it a playboy breaks dates with three different women to take a fatal drive by himself. Epstein uses four different cinematic styles to represent the perspectives of the four characters. At the time the film was released he published the essay “Event Art,” in which he wrote:

And two women, unknown to each other, by means of sixty feet of film, are brought together in the eye of the viewer, and there only is their true note sounded: just as the notes of a chord separated by a half-octave surrender their musical significance only in the ear of the musician. Banality is the least relative sign of truth. This studied, searched out, decomposed, multiplied, detailed, applied banality will give the cinematographic drama a striking human relief, a hugely increased power of suggestion, an unprecedented emotive force.

The accelerated or slowed-down events will create their own time, the time proper to each action, to each character, our time. In elementary school, the first compositions are written in the present tense. The cinema tells everything in the present, right down to the subtitles. As they learn more grammar and rhetoric, the students begin to mix pasts and futures in their stories, bringing them into harmony. The fact is that there is no real present; today is a yesterday, perhaps an old one, which obliquely bears a tomorrow, perhaps a distant one. The present is an uncomfortable convention. In the midst of time, it is an exception to time. It escapes the chronometer. You look at your watch: the present, strictly speaking, is gone already, and strictly speaking, is there again. It will always be there from one midnight to the next. I think and therefore I was. The future “I” bursts into a past “I”; the present is nothing more than this instantaneous and incessant molt. The present is only a meeting.

Cinematography is the only art that is capable of representing it as such.

A careless motorist seems an insignificant character; a swallow on the wing, even more so; their meeting: event. This tiny spot engraved by the bird’s beak on the man’s forehead, had against it the will of three hearts, the miraculous vigilance of love, all the probabilities of the three dimensions of space, all the chance of time.

But it took—it’s the proper word—place.

Supersaturation freezes the crystal in an instant. So it is with the drama, like the egg at the fingertips of the naked magician, come out of nothing, of everywhere. All around, characters and actions, submissively fall into order. Toward the future lies a false track which in its turn will undergo the surprising intersection with the absolute. Toward the past, the idyll, read backwards, is tragedy. The episodes each find their place, in order, deduced, bound together, comprehensible, understood. Exactly—the actors intimate—that’s why we were there. As in the beautiful syntax of a Latin sentence, from the final verb, you come back to the subject.

The superabundance of musical, linguistic, and temporal models suggested in this brief passage is characteristic of Epstein’s early theoretical writings. He was fundamentally an avant-garde figure, although he was never comfortable within any avant-garde “movement.” In the two early texts, he writes of the essence of cinema and of the avant-garde. His ideas overlap in both essays, as he is attempting to expand and illuminate the concept of “photogénie” which his predecessor Louis Delluc introduced into French film theory. For Epstein, the photogenic, or what is essentially cinematic, demanded a dialectical relationship to any given technique, which he considered merely contingent, and entailed the recognition of interrelationships among space, time, and material things within the radically idealistic structure of filmic illusion.

In his later texts, he demonstrated his philosophical training by bringing the ideas of the Pre-Socratics and Spinoza to bear on film theory, showing how the relativity of camera speeds could underline the paradoxes of both atomism and pantheism. The tendency which I have somewhat arbitrarily called “subjective” (to distinguish it from the graphic) raises a series of questions about the character of cinematic representation while operating within the spatial and temporal conventions of the dominant cinema, often to subvert them. Drawing its model from oneiric activity, the subjective cinema needs photographic illusionism to constitute one of its essential moments; the other being the discontinuity of montage. Three examples of silent Surrealist cinema will illustrate this tendency: Etoile de Mer (1928) by Man Ray and Robert Desnos, La Coquille et le Clergyman (1928) by Germaine Dulac, and Un Chien Andalou (1929) by Salvador Dalí and Luis Buñuel.

Etoile de Mer operates through a series of polarities which variously contradict and converge upon each other; word/image, conventional photography/anamorphosis, and images and words in opposition to their referents. Early in the film the title “Les dents des femmes sont des objets si charmants . . .” is followed ironically with a shot of a woman’s legs. The comic substitution of legs for teeth manifests a deeper allusion to the vagina dentata, a mythic obsession that seems to motivate many of the images of the film from the initial shot of an opening doorway photographed through stippled glass so that it suggests a female sexual organ, through an otherwise unaccountable scene of impotence in which the contemplative hero bids “Adieu” to the woman he is pursuing the moment she strips herself before him, to finally, the image of a living starfish that he holds in a glass cylinder, as a metaphor for the vagina dentata.

The first title, “Les dents des femmes . . .” completes itself with “Qu’on ne devrait les voir qu’en réve ou a l’instant de amour.” Thus the model of the dream is immediately introduced into this film. The relationship between the film experience and dreaming, as well as the privileged access of cinema to representing the dream work, are persistent themes of the avant-garde film. In the American films of the 1940’s this will become the major mode of independent filmmaking. Man Ray and Desnos however are not content to stop at the dream suggestion. In the rest of the film they gradually dissect the junctions of picture and text. When the titles announce that the woman of the film is “belle comme une fleur de verre” the poetic text puns upon itself (verre/vers) and gestures toward the mediation of the stippled glass through which most of the film is anamorphically recorded and even towards the latent sheets of glass in all lenses.

Germaine Dulac, La Coquille et Le Clergyman (1928)

Germaine Dulac brought to film theory her formulation of the concept of pure cinema. When she made La Coquille et le Clergyman she was entering a crucial stage of her film-making career. Later that same year she completed the much more artistically successful film, L’Invitation au Voyage, which like her earlier La Souriante Madame Beudet (1923) impressionistically explores a woman’s erotic day-dreams and her dissatisfaction with her daily life. The following year she realized three important short films, Disque 927 and Thémes et variations (two abstract montages of images inspired by classical music) and the slow-motion nature study Germination d’un Haricot. In 1929 she made another abstract film, this time inspired by Debussy’s Etude Cinégraphique sur une Arabesque.

In La Coquille et le Clergyman, Germaine Dulac attempted to do justice to a script by Antonin Artaud. Artaud seems to have detested the film. Together with some Surrealist friends he caused a commotion at its opening and had to be removed from the theatre. Nevertheless, one would not surmise from his writings on cinema the degree of his rejection of the film was exaggerated. In the essay “Cinéma et abstraction,” he praised the actors and thanked Dulac for her interest in his script, “which seeks to penetrate the essence of cinema and does not pay the slightest heed to art or life.”

Of the scenario itself he wrote in the same essay:

…from It does not tell a story, it develops a series of mental states, which proceed one the other like thought deduced from thought without reproducing a logical chain of events. From the collision of objects and gestures real psychic situations deduce themselves between which the cornered intellect seeks a subtle escape.

Dulac employed slow motion, split images, and optical distortions in her adaptation of the scenario about a priest’s displaced lust for a beautiful woman who comes to his confessional.

Artaud had no patience for the exploration of pure cinema. “Sorcery and the Cinema,” affirms the power of raw cinema, even unenhanced by the technical options of transformation through the camera, to assume a central role in art, at the moment when the symbolical power of language (“son pouvoir du symbole”) was dissolving, by repudiating narrative and seeking a “subtle,” “secret,” and internalized order among images.

The implicit dialogue between the texts of Dulac and Artaud approximates the exchange between Vertov and Eisenstein (“intervals” vs shock effects) and anticipates the theoretical debates within the American avant-garde cinema. On the one hand, she had a vision of a pure or essential cinema, the pursuit of which would constitute a radically new genre or film. On the other hand, some theoreticians seize upon the idea of an important and revolutionary change in art as a whole for which cinema would be the perfect vehicle. Interestingly both positions appropriate metaphors from music and language to justify their claims.

Un Chien Andalou is one of the purest examples of Surrealist cinema, which rejects the exploitation of imagery engendered by the camera. Robert Desnos, who was a film reviewer as well as a poet, used the occasion of its première to attack Epstein, Gance, L’Herbier, and the idea of what passed for an avant-garde cinema in general. He gave it a higher status than Entr’Acte (1922) or L’Etoile de Mer (both of which he admired) and considered it among the highest achievements of the cinema, along with the films of Chaplin, Stroheim, and Eisenstein, as a work “indisputably human, sane, and poetic.”

Luis Buñuel, Un Chien Andalou (1929)

In Un Chien Andalou the examination of cinematic principles is shifted completely to the level of temporality. It is as if the camera had the same access to the visible world as a windowpane. In fact, in the middle of the film, when the protagonist looks lustfully down upon the androgyne hit by an automobile, he presses his face against the upper story window from which he is watching her. The window as a barrier through which the visible world enters but which cannot be transgressed; it is an icon of Buñuel’s and Dalí’s conception of cinema. Like the major Surrealist painters, especially Magritte, they accepted three-dimensional illusionism as the “rational” ground for irrational juxtapositions. In this film the juxtapositions take place sequentially but are edited so as to appear, through the second illusionism of narrative montage, simultaneous.

They employed the strategies of metaphor, synecdoche, and metonomy by which the simultaneity is sustained become the structural models of the film’s formal development. For instance, the opening of the film elaborates a visceral metaphor in which a thin cloud passing before the moon is substituted for an image of a razor slicing a woman’s eye. However, immediately after the metaphoric substitution which suggests, without representing, the horrible operation, the filmmakers show us the vitreous fluid flowing out of the eye. The metaphor has called attention to its own failure as a substitute and yet has provided the moment for a subtler substitution in which a cow’s eye, in close-up, can be substituted for the woman’s eye. We see, then, in immediate succession an antithetical metaphor, whose very calmness evokes terrible violence, followed by an even more violent synecdoche.

The figure of synecdoche is thematically analyzed in the middle of the film when the protagonist is seen contemplating his hand. A following shot shows the hand alone with ants crawling out of a hole in the palm. This synecdochical illusion engenders a series of metaphors (a sea-urchin and a woman’s armpit) ending in an image of a crowd of people gathering outside on the street around the androgyne like ants around the hole. The supervising policeman gives the hermaphrodite a severed hand, itself a metaphor for a synecdoche.

3.

Le Sang d’un Poète (1932) Jean Cocteau’s first film, bridges the transition from an avant-garde cinema centered in Paris to one dominated by Americans. For of all the independent films from Europe this one had the most influence on those Americans who would revive the avant-garde cinema toward the end of the Second World War. Two aspects of Cocteau’s film give it this privileged position: its manifestly reflexive theme, and its ritual. The film opens with an allegory of the relationship of the authorial persona to the temporality of cinematic representation. We see Cocteau, surrounded by the klieg lights of a movie studio, blocking his face from the camera with a classical dramatic mask, which foreshadows the moment in the film when the filmmaker will declare in a handwritten title that he is trapped in his own film; yet what we see of him then is still another mask, this time fashioned after his own profile. The declaration of the enigmatical distance between the authorial self and his mediating persona is coordinated with a bracketing device that affirms that the film transpires in no time, or in the instant between two photograms. We see a towering smokestack begin to crumble, an image reminiscent of many of the Lumiéres’ one-shot films. At the end of the film the smokestack completes its fall.

Jean Cocteau, Le Sang d’un poète (1932)

The Hotel des Folies Dramatiques which the poet explores after crossing the threshold of the mirror is a series of rooms, accessible only to sight through their keyholes. In each, a principle of cinematic illusionism is illustrated with the naive exuberance of Méliès films which Cocteau must have first encountered in his childhood. The assassinated Mexican is revived in reverse motion; camera placement allows us to see a girl clinging to walls and ceiling; finally, a hermaphrodite is constructed of flesh, drawn lines, and a roto-relief in Duchamp’s style so that it is not only an illusionary blending of male and female characteristics but a figure synthesized from the very arts which feed into cinematic representation. The myth of the poet that Cocteau elaborates moves freely among centuries and between childhood and maturity.

The temporal ambiguity that Cocteau postulated between any two consecutive frames of a continuous shot operated independent of the camera which photographed that shot. In Maya Deren’s reworking of that suspended temporality, account would be taken of the status of the camera in cinematic metaphors of reflection. She did not do this as Vertov had done, and as many would begin to do in the 1960’s, by introducing the filmmaking apparatus into the imagery of the film. Her early, and best, films dwell instead upon the temporal and spatial complexities of representing the self in cinema. In Meshes of the Afternoon (1943), which she made with her husband, the filmmaker Alexander Hammid, there is a moment after the heroine, played by Deren herself, has fallen asleep when she dreams of seeing herself. She stands before a large window, looking out upon a bright California landscape in mid-afternoon, with her hands pressed against the glass. A reverse shot from outside shows her hair blended with the reflection of off-screen trees, her hands defining the barriers of the glass, and her eyes in a distracted, almost narcissistically inward gaze. The montage will establish that she is watching herself through the window repeating with symbolic displacement the very entrance to her house that preceded her sleep.

Here the window, as a metaphor for cinematic representation, has neither the amorphous presence of Man Ray’s distorting lens or the barrier quality of the window in Un Chien Andalou; it is, rather, a mirror. For Deren, and subsequently for most of the American independent filmmakers who followed her, filmmaking was essentially a reflexive activity.

In many of the American films of the 1940’s the reflexive relationship between the authorial subjectivity and the Selfhood represented in the film was mediated simply by the filmmaker’s crossing over to become his own central actor. Deren did this in three of her first four films. Yet more significant than this elementary transformation of the fiction into psychodrama was the elaborate structure of metaphors by which these films comment upon the problematic status of their imagery and their temporal structures. In her last essay, “Cinematography: The Creative Use of Reality,” she formulates a reflexive relationship between a photographic representation and the world in the passage in which she writes of the “implicit double exposure” which the mind makes in recognizing the reference of a photographic image. In Meshes of the Afternoon, the mirror metaphor has an entire morphology: she pursues a black figure who turns out to have a mirror for a face; at the climax of the film, a knife that had menacingly recurred several times before, reflects her face just before she plunges it into the face of her lover finally that violent attack turns out to be a stab not at his flesh but at its reflection in still another mirror.

Maya Deren, Meshes of the Afternoon (1943)

Throughout Deren’s work the cinematic image has the fragility of a mirror image. At Land (1945) works out more meticulously the temporal status of this imagery. In that film, Deren portrays herself as washed out of the backward rolling sea. Once on the shore, she begins a quest through several contrasting landscapes, ostensibly in search of some stable sexual identity. As she moves from one landscape to another, the compositions and the allusions to off-screen space are so coordinated as to make those disparate spaces seem continuous. In fact, with A Study in Choreography for Camera (1945) she generated an entire short film from this principle: the stretch, spin, and leap of a dancer through radically different spaces is portrayed as one continuous gesture. Implicit in such spatial paradoxes is the recognition of temporal disjunction between the time of filming and the time of representation. In At Land this disjunction becomes thematic at the end of the film. There is a retrograde recapitulation of the principal scenes of the film in each of which the heroine is looking off-screen. She introduces a new shot between each of these repeated elements showing the same heroine in approximately the position that the camera must have occupied to take the earlier one. A corresponding off-screen glance thus links the two versions of the same spatial field in an illusionary exchange of looks. Here she has not only pushed the metaphor of the mirror into a formal mechanism, but she has also accounted for the temporary omniscience of the camera and prepared the way for a final image in which the problematics of cinematic representation find a culminating metaphor. The shot begins with her feet as she runs along the sand of the beach where she first was seen; as the camera pans from her footprint to her running figure she has travelled much farther than the time of the pan could allow. Here through an elementary trick of stopping and starting the camera the temporal instability of the most elementary cinematic successiveness (that within the shot) is demonstrated.

Furthermore, the choice of imagery is significant. For a footprint is an indexical sign (in the trichotomy of C.S. Peirce); that is, it both signifies the passage of the runner and it simultaneously seems to have been caused by that runner. A bullet hole is another indexical sign; so indeed is a photograph. Photography, and therefore cinema, seldom fully escapes from the seduction of the indexical, which postulates at some earlier time the phenomenal presence of a camera to its object. The ambiguity of this polarity and its problematical “presence” in past time is the very theme of Deren’s At Land.

4.

Maya Deren called herself a Classicist to distinguish her theoretical position from both the Surrealists and the practitioners of the graphic cinema (which she felt was nothing more than a form of painting in cinema). For her the central contribution of cinema was its temporal dimension. For her this meant accepting the conventions of spatial representation according to the dictates of the traditional lens and registration apparatus as the very ground for cinema. She wrote: “If cinema is to take its place beside the others as a full-fledged art form, it must cease merely to record realities that owe nothing of their actual existence to the film instrument.” Also, “The impartiality and clarity of the lens—its precise fidelity to the aspect and texture of physical matter—is the first contribution of the camera.” Its other and more fundamental contributions allow for the transfiguration of temporal complexes. The polemical position was first answered in the American context by the work of Sidney Peterson.

After an initial collaboration with the poet James Broughton on the film The Potted Psalm (1946), Peterson made a series of films under the limited sponsorship of the California School of Fine Arts where he taught what was probably the first class in avant-garde filmmaking. The Cage (1947), the first film to emerge from that situation, combined the subgenres of the city symphony and what I have called “the trance film” in my extended study of the American avant-garde film, Visionary Film (1974,1979, 2002).“trance film” is meant those subjectivistic films in which a protagonist wanders through a menacing or mysterious landscape, as if entranced. in quest of an epiphany of sexual identity. In The Cage a young painter dislodges his eyeball while attempting to expand his realm of vision. The subsequent imagery of the film alternates between a view of San Francisco from the point of view of the freely wandering eyeball, and the allegory of its pursuit by the wounded painter, his girlfriend, and a malevolent medical doctor.

What is most interesting about the film is the way in which the theme of consciousness as pure vision that has been part of the American aesthetic tradition since Emerson and that dominates much of the theory of Abstract Expressionism, receives its filmic treatment. The liberated eyeball experiences a fundamentally temporal disorientation; it is incapable of seeing sequentially; it even sees forward and backward motion simultaneously. Peterson cinematically explored the postulate that temporality is a bodily rather than a visual function.

One of his most successful films, Mr. Frenhofer and the Minotaur (1949) combines elements of Balzac’s novella Le chef d oeuvre inconnu, Joycean interior monologue, and the imagery of Picasso’s “Minotauromachie.” The rhythmical intercutting of elliptical scenes from the story, as well as shots of two characters reading the story, images from the etching, and a continual monologue of puns, allusions, displacements, and metaphors, makes for a system of shifting levels of reference in a complex interplay between the passions of artists and the passions depicted in their art; between the act of modeling as a paradigm of film acting, and the representation of the model in painting, film, and dream. The shifting images are visually unified by the consistent use of anamorphic photography.

Sidney Peterson, Mr Frenhofer and the Minotaur (1949)

Peterson described his ambitions in making Mr. Frenhofer and the Minotaur thus:

It was my decision to do a thing about the Balzac story, taking seriously as the theme of the story the conflict between Poussin’s Classicism and its opposite. So strained through my mind it became really a way of exploring the conflict stated in Rousseau’s remark to Picasso: “We are the two greatest painters; you in the Egyptian manner, and I in the modem.

In the dialectical history of the American avant-garde film, Peterson reformulated the Picasso-Rousseau distinction as one between himself and Deren. He refused to accept the clarity of the conventional lens as a value. Instead, he insisted upon a cinema in which the very space of representation was invented by the filmmaker. Thus, in his ironic rendering of the Balzac story Frenhofer’s palimpsestic destruction of the portrait of the ideal woman became a visionary forecast of Abstract Expressionism, while the fantastic imagery of Picasso’s etching became another form of neo-classical idealism.

James Broughton’s filmic practice has tended to overlap with his activity as a poet and director of plays. Several of his films are organized with the economy and frontality of a theatrical production. This is not to say that Broughton is unaware of the specificity of cinema: in Mothers’ Day (1948) he concentrates upon the temporal disjunctions between memory and its cinematic representation. The film takes the form of a family album in which the narrator attempts to reconstruct both his own childhood memories of his mother and the myth she has told of her courtship and marriage. Throughout the film the temporal figures continually shift into psychological metaphors. For example, the first image of the mother framed in the upper story window of an old house is followed by an image of a similar house in an advanced stage of destruction. The coupling of the shots emphasizes the irrevocable loss of time while at the same time the mother is identified with the empty facade of the structure. All through the film, the mother’s children are represented as adults playing children’s games; here again the temporal bind in which the narrator can only picture the children as grownups blends into the metaphoric perspective of childish adults. Broughton uses the cinema for both the evocation and the analysis of an ironic nostalgia. In Mother’s Day, the cinematic tropes, the costumes from various periods, the representation of children’s games by adults, and the formal association of the whole film with a family album, all serve to undermine the presence of the images and to locate the film in the mind of a remembering subject.

In many of his subsequent films, such as The Adventures of Jimmy (1950); Loony Tom, The Happy Lover (1951) Four in the Afternoon (1951); and This is It (1971), the interplay of verse or prose narration with the imagery creates comparable disjunctions of time. Broughton, like his contemporary Willard Maas, was poet before he became filmmaker and like him, he believed that Cocteau’s Le Sang d’un Poéte provided the essential model for the avant-garde film of the future: a welding of montage and poetic language.

James Broughton, Mother’s Day (1948)

In his notes to Mother’s Day, Broughton emphatically aligns himself with the position of Maya Deren, even including her favorite metaphor of choreography, against the Dionysiac cinema of Peterson (“camera trickery”). In his cyclic films, Four in The Afternoon, The Bed (1968), The Golden Positions (1970), Broughton incorporates choreographic movements into comic schemata of essential life rituals.

5.

Kenneth Anger too has worked within the spatial framework of the dominant cinema. His first publicly screened film, Fireworks (1947), describes a double dream in sado-masochistic homosexual imagery. Significantly, a photograph occupies a central and paradoxical position within the film as either the source or the residue of the dream. An opening passage of the protagonist held in the arms of a sailor, followed by a scene of the same protagonist waking, suggests that the former was his dream. This seems to be reinforced by the fact that a photograph, showing the same image as the dream, lies by his side, as if the source of his nocturnal masturbation fantasy has become “animated” in his sleep. Yet as the waking day proceeds, its mimesis veers progressively towards ironic displacements: for a match is substituted a bundle of burning sticks; for a heart, a metallic meter; for semen, cream; for a penis, a roman candle. The internal evidence then suggests that we are still within the oneiric model even before we see the final image of the protagonist still sleeping. What terminates the dream and allows us to see the sleeping figure unmediated by his own imagination is the burning of the very photograph which seemed the source of the dream. Here the space and time of the dream coincide with the duration of the photograph as a fetishistic object occupying a twilight area between an experience of dubious authenticity and the awakening into a full present which is continually postponed.

Kenneth Anger, Fireworks (1947)

The filmic dream constituted for Anger, as it had for Deren, a version of the perceptual model that generated most of the subjective films of the American avant-garde. Whenever that model is operating, a subject/object polarity is established so that the camera’s relationship to the field of its view reflects the functioning of a receptive mind to the objects of its perception. The metaphor of the dream permits the reflexive gesture of duplicating the presence of the filmmaker (subject) or his mediator in front as well as behind the camera. The introduction of photographs or other iconic representations as objects of the camera’s gaze merely adds another reflexive turn within the model without altering it.

Thus, Mother’s Day postulates an organizing consciousness involved in some variant of nostalgia. Likewise, the anamorphosis of Peterson’s films pointed to a radically askew perspective grounded in a being upon whom the psychological and intellectual tensions of each film converged. As long as this model dominated the forms of this mode of filmmaking, the works it generated hovered near a solipsistic reduction of psychology to a transcendent self and a dialectically opposed Otherness, and naturally excluded were either the possibility of elaborating an interplay of several developed characters or the formal recognition of the mediating presence of a film viewer.

One of the most subtle and nuanced inflections of this model, and one which had enormous influence, was manifested in the cinema of Marie Menken. In a remarkable series of disarmingly unpretentious films, she demonstrated a rhythmic inventiveness perhaps previously unmatched in the cinema. In Notebook (1945-62) she stored fragments from all phases of her. There we can see how, at a cinematic career, from the mid-Forties to the Sixties time when most of her contemporaries were invoking the Dionysian imagination in their invented imagery, she was exploring the dynamics of the edge of the screen and playing with distinctions between immanent and imposed rhythm. The early and exquisite “Raindrops” dramatizes the subtle wit of Menken’s version of the perceptual model. As she waits behind the camera for a drop of rain on the tip of a leaf to gather sufficient mass to fall, we sense her impatience and even anxiety lest the film will run out on her; so an unseen hand taps the branch, forcing the drops to fall. Tampering in this way with an otherwise straight-forward observational film is characteristic of Menken, who cheerfully incorporates the extraneous reflection of herself and her camera, even her cigarette smoke, into an animated film and who makes the very nervous instability of the hand-held camera a part of the rhythmic structure of several films.

Marie Menken, Arabesque for Kenneth Anger (1961)

In Arabesque for Kenneth Anger (1961) she offers her fellow filmmaker a version of his earlier Faux D’Artifice (1953). There Anger had made a water-dominated counterpart to his initial fire ceremony, Fireworks. A figure in a Baroque dress emerges from a fountain, which evokes a penis in orgasm, in flight or pursuit through fountains of the Tivoli gardens. The entire film was tinted a deep blue and suggested the night passage of a frail psyche through an overpowering and menacing landscape until her eventual metamorphosis back into a fountain. Menken in contrast filmed a visit to the Alhambra in midday, achieving a comparable deep blue tone through the deceptively naturalistic choice of light sources and conventional blue-sensitive film stock. The spiraling flight of a pigeon among the roofs of the Alhambra provides her with an initial rhythmical figure and a metaphor for her wildly eccentric camera movements. Against this she plays the second metaphor, again deceptively naturalistic, of architecture reflected in a pool; a metaphor for the cinema’s reduction of spatial configurations to a shimmering two-dimensional surface. The circles and swirls that her revolving camera imposes upon the Moorish structures can then be found translated into the rings that drops of water make in the pools reflecting the same buildings. This delicate mesh of observation and imposition that appears in almost all of Menken’s films, inspired Stan Brakhage, who radicalized it and systematically explored its potential for the articulation of a new form within the avant-garde cinema.

6.

Brakhage’s Anticipation of the Night (1958) took up the opening of Meshes of the Afternoon and elaborated it in terms of a Petersonian consciousness. We see those parts of the body which a subject sees of himself: the shoulders, the legs, and especially the outlined image it projects as the shadow. The shadow man of Anticipation of the Night leaves his home at the beginning of the film and encounters a series of sights of the natural and human universe as stations of imaginative loss which ultimately lead to his suicide at the end of the film.

Stan Brakhage, Anticipation of the Night (1958)

In this film, Brakhage fully achieves for the first time a dialectical fusion between the image represented on the screen and the filmmaker/subject’s reaction to it.constantly moving the camera intimation of the movement of the eyes and the fluctuations of attention, and by editing the movements in rhythms that suggest both the sudden and the gradual intrusions of memory and anticipation on the flux of the present, Brakhage mediates the visual world without a mediator. In his subsequent lyrical films, the shadow man disappears, and the montage will directly represent vision and thought.

According to Brakhage’s theory, vision has at least three aspects. The first is open eyesight which is a continual flux of focus and movement, sensuously probing the actual world that manifests itself before the eyes. The entire cinematic tradition, he would claim, had ignored this mode of primary seeing before him. Secondly, he describes “brain movies” as images of the past or fantasies which briefly emerge before the visual imagination as if filmed from a fixed tripod. In this respect he is close to the brilliant early theories of Hugo Munsterberg, who claimed that cinema did not record the actual world so much as the reflective processes of the mind. Finally Brakhage would include the representation of “closed eye vision, ”the phosphenes which appear when we close our eyes in moments of intense psychological stress. All three modes of seeing merge together in his lyrical films.

Reading Gertrude Stein, Brakhage found a narrative mode which corresponded to his theory of vision and which guided his theory of temporality. All of Brakhage’s lyrical films operate upon the fiction of a man, the filmmaker, looking upon a natural sight and responding to it imaginatively. That encounter is always conceived as a crisis and the moment of the crisis provides the present tense and ground for the temporal ecstasies. For Brakhage, the cinema is primarily a visual medium with no direct means of representing a past which has not been recorded on film, and certainly no future. He rejects the fictional dramatic film and bases his concept of temporality upon the discontinuity between shooting and editing.

At the beginning of his theoretical book, Metaphors on Vision, Brakhage was to write:

Imagine an eye unruled by man-made laws of perspective, an eye unprejudiced by compositional logic, an eye which does not respond to the name of everything but which must know each object encountered in life through an adventure of perception. How many colors are there in a field of grass to the crawling baby unaware of “Green?” How many rainbows can light create for the untutored eye? How aware of variations in heat waves can that eye be? Imagine a world alive with incomprehensible objects and shimmering with an endless variety of movement and innumerable gradations in color. Imagine a world before the “beginning was the word.

Early in Anticipation of the Night the shadow man attempts to imaginatively reconstruct the adventure of grass to a preverbal infant. The camera moves through leaves and grass, encounters and pursues a rainbow, explores the tactility of ground movement and ultimately reveals the mediation of a crawling child whom the shadow man observes. The very structure of the sequence as hysteron-proteron, in which the childlike vision is imitated before the child is seen, suggests the ultimate failure of the imaginative attempt. Somewhat later the filmmaker sees children delighting in the rides of an amusement park at night and tries to participate in their rapture, moving his camera in sympathy with their whirling movements. Finally, near the end of the film he sweeps over the sleeping bodies of children. Their stasis emphasizes the isolated consciousness of the filmmaker. In this final and most extravagant attempt at recapturing the freshness of their vision he tries to imagine their animal dreams. Here the recovery is the strongest in the film, perhaps because it is without an external guiding gesture, but it too fails with the breaking of dawn and its implicit reduction of the entire quest for renewed vision to a nightly cycle. In the end, the hand of the shadow man fastens a rope to a tree and hangs himself.

7.

By the early 1960’s those forms I have been describing no longer seemed to satisfy the most ambitious filmmakers. They began the elaborate mythic structures that equated the dialectics of individual consciousness with the elemental struggles of gods, demigods, much as the Romantic poets, Blake, Shelley, Hōdlderlin, and Hugo had done. The major works of this phase, such as Anger’s Scorpio Rising (1963), Markopoulos’ The Illiac Passion, (1967), Harry Smith’s No. 12 [Heaven and Earth Magic], (ca. 1963), Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures (1963), Brakhage’s Dog Star Man, (196`-65) and Jacobs’ then unfinished The Sky Socialist (1968) substitute archetypal conflicts for narrative exposition. The plurality of figures they present as gods or titans are interiorized beings, and although the drive towards the mythopoeia represents an attempt to overcome the solipsism of the trance film and the lyrical film where the perspective is reduced to a negative selfhood and a menacing landscape (or otherness), the resulting films for the most part offer fragmented or unresolved myths that incorporate metaphors of their own failure to escape solipsism.

Ken Jacobs, The Sky Socialist

Each of the central works of the mythopoeic phase presents its own mode of mythology and its own strategy for questioning the authority of its mode. Kenneth Anger’s Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (first version, 1954) depicts a convocation of Egyptian and Hellenic deities under the control of a Magus and a “Scarlet Woman” from the mythopoeic imagination of his chosen master, Aleister Crowley. From the opening ritual of waking and dressing, the film acknowledges the ad hoc nature of its divine personifications. It is both the making new of ancient myths and a contemporary masquerade. The turning point of the film, the poisoning of Pan and his subsequent sparagmos, coincides with the assuming of new masks and the compounding of guises.

Only the first of Jack Smith’s three major films, Flaming Creatures, Normal Love (begun 1963), and No President (1967) was definitively completed and distributed. All three exploited the chemical changes that occur in film stock not used until long after the recommended time range for exposure. Smith derived this heightened textural ambiguity from seeing Ron Rice’s picaresque portrait of a beat poet, Taylor Mead, in The Flower Thief (1960). However, he carried it to an extreme that Rice had not exploited.costuming his actors in black and white gowns before flagrantly artificial white backdrops, he capitalized upon the tendency of outdated film stock to wash toward whiteness. In the color film Normal Love, a comparable pastel effect was achieved by elaborating an imagery that would coincide with the tendencies of outdated color material.

While Anger’s Scorpio Rising describes the limitations of the mythopoeic imagination by grounding it in Hollywood and historical archetypes, Flaming Creatures offers a more complexly ironic version of the dialectic play of imagination and nature. In the pivotal scene of the film an act of imagination, or more exactly of the fancy, engenders a physical convulsion: the camera responds to a comic orgy by gyrating in sympathy to it; yet before the orgy is over, an earthquake occurs and the same spastic movement is presented again as a response to the natural disaster.

Jack Smith, Flaming Creatures (1963)

A very different relationship between editing and mythopoeia can be found in the long films of Gregory Markopoulos from this period. In his early films Psyche (1948) and Swain (1950), he had used impressive montages of recapitulation as an organizational principle in the former and as the climax of the latter. Twice a Man, Markopoulos’ version of the myth of Hippolytus, employs a complex schema of memory within memory and a shifting mediation in the minds of four figures.

The ambiguous movement between recollection and prolepsis in this film is grounded in the very structure of the editing of every shot. Rather than directly splice one shot to the next and build his dynamics on the stress accent of the point of change, as in the classical montage of Eisenstein, Markopoulos will introduce one or two frames of the forthcoming shot before the “present” shot is completed; he also allows a series of brief flashes from the former shot to recur periodically as echoes after the former shot has ended its dominance. Thus, one image breaks into the next in a moment of vibrating fusions of past, present, and future time. With this structure operating throughout the film, Markopoulos can introduce metaphors and complexly bracketed themes into his montage; he can also shift easily to extended passages of recapitulation.

Gregory Markopoulos, Twice a Man (1963)

The filmmaker saw in this system an affirmation of the priority of montage over spatial transfiguration in the tradition I have associated with Maya Deren. In a crucial essay, “Towards a New Narrative Film Form,” he joins her in rejecting the use of filters, anamophosis, or any other means of transforming the elementary spatial givenness of the cinematic image. He extends her commitment to the immanent aesthetics of the filmic material in a direction she never took, when he points out that the fact that all films are a strip of still, rapidly changing, frames has been “understood only as a photographic necessity.” He emphasizes that rather than being a contingent fact about cinema it is the potential source of its primary structures. The elaboration of the operations of the single frame then became the focus of Markopoulos’ later theoretical work.

The Romantic myth of a divided and reunited Selfhood is the subject of Harry Smith’s Heaven and Earth Magic. There a female figure of Smith’s film is the major instance of an animated mythopoeic film and also the example from this phase that most fully uses combined sound and image to attest to its fictionality. At the very beginning of the film, as the magician brings into the frame the basic elements out of which the woman will be initially constituted, we see him exit on screen right and then reenter from screen left as if he had walked around the back of the screen. Similar acknowledgements of the illusion of animation occur throughout the film. Figures move along arbitrary imagined lines against the back of the screen until suddenly a bridge will appear and they are bound to cross it as the only possible line of movement in the field of vision.

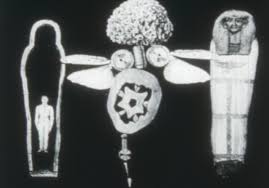

Harry Smith, Heaven and Earth Magic (1957)

As a work of the graphic cinema Smith’s film has a fundamental orientation toward the reorganization of spatial illusion. He wittily acknowledges this near the opening of the film when the magician pulls a photograph of a watermelon patch into the frame. The photograph has a horizon in Renaissance perspective, but the frame of the film does not. He takes a watermelon out of the photograph for his manipulation in the more ambiguous black field of the film. When Smith speaks of sources for his mythopoeia, MacGregor Mather’s presentations of the Kaballah, Wilner Penfield’s open brain surgery on epileptics, and especially D. P. Schreber’s Memoirs of My Nervous Illness, a link between radical myth-making as an exploration of the complexities of the self and paranoia manifests itself. Brakhage’s major work on cinematic mythmaking, Dog Star Man, (1961-64), also presents a radically individualized spatial field and explores divided consciousness and its self-inflicted torments.

Stan Brakhage, Dog Star Man (1964)

The making of Dog Star Man occupied a crucial period in the development of Brakhage’s exceptionally influential theories. His book, Metaphors on Vision (1963), was edited and published during this period, even though some of its texts go back to the mid-Fifties. Here Brakhage articulated, in his involuted punning prose, the most radical version we have yet had of the Emersonian strain in American film theory. Cinema, according to Brakhage, aspires to the representation of the full range of optical sensations experienced by the filmmaker, in active vision, in memory, and even with the eyes closed.

Much of the complexity of Brakhage’s writings derives from the ironies of formulating in words a theory of the interference of language with vision. One strategy he has used to control this problem has been to mediate his text with profuse allusions and quotation of poetry (as the place where language is most self-aware). In the letter to Yves Kovacs, he reinterpreted the influence of Surrealism by bringing it into alignment with recent American poetics. In the late 1980s he relentlessly documented the breakup of his marriage to Jane Collom, Then he made the exceptional series of Visions in Meditation (1989-90) and married Marilyn Jull. Because she did not want to be filmed, he made a series of films on Vancouver Island (where he retired) to fuse his vision with what he imagined had been hers, growing up there. Prolific to the end, he also made his longest sound film (Passage Through:A Ritual, 1990) and nearly one hundred hand-painted films before his death in 2002.

Bruce Baillie, Castro Street (1966)

Bruce Baillie’s major films occupy a region between the early lyrical films of Brakhage and the mythopoeic cinema that followed. To Parsifal (1963) Mass for the Dakota Sioux (1964), Quixote, 1965/67), even Castro Street (1966), Valentin de las Sierras (1971) and Roslyn Romance (Is It Really True?): Intro. 1 & II (1978) are heroic poems without heroes. The characteristic strategy of Baillie was to find an image of exaltation or liberation—in the movement of a train, the wind in the grass, a flying spaceman, a motorcyclist, or a particularly sympathetic and usually aged face—which is at first valorized of natural and musical sounds. Yet the more sinister implications of these metaphoric vehicles are seldom far removed. In Mass and Quixote this tension within the imagery is polarized by an explicitly political structure and the ironic use of filmic quotations (from advertisements and commercial films) which specifically attribute a negative value to cinematic representation. Castro Street and Valentin de las Sierras lack the social context of the earlier films and rely more heavily on the ability of sensuous imagery to convey the antithetical structures of meaning. In fact, it is as they veer toward the apogee of this sensuousness that the contradictory movement is initiated: in Castro Street it is the slow movement of the train through a field of flowers that raises the polarity of natural and mechanical consciousness which is deceptively couched in the center of the film; while in Valentin de las Sierras the close loving attention to the wrinkled flesh of the ancient guitarist, whose song gives the film its title, reveals that he is blind. His blindness intensifies the pathos of his song and underlines the optical scrutiny of the wandering filmmaker, who in this film presents himself as entering on horseback, but unseen, the village he records in a rich texture of close-up synecdoches. In his very attention to detail the filmmaker seems to be avoiding any direct glance that would acknowledge his presence; in place of a self-image, he offers us the moving shadow of the horse which brings him to and away from his subject.

8.

While Deren, Broughton, Peterson, Markopoulos, and Brakhage were mining their Surrealist, Dadaist, and Constructivist sources for a cinematic vocabulary with which to formulate crises of the self, another group of young American artists turned back to the geometrical abstraction of the Germans in the 1920s to revive the graphic cinema. Oskar Fischinger’s presence in Hollywood during these years was a mediating influence. So was that of Len Lye in New York. Along with Ruttmann, Richter, and Eggeling, Oscar Fischinger had been one of the originators of the geometrical style in filmmaking. Unlike all the others, he continued that work until the 1950s. The coming of sound film helped him to realize his theories of synchronization between music and image. Lye, a New Zealander, may have been the first filmmaker to paint images directly on film (others had certainly tinted shaped outlines before him). His work in England throughout the 1930s marks the highpoint of the fusion of kinetic montage with abstract color dynamics in the cinema.

The younger Californian graphic film-makers Harry Smith, John and James Whitney, and Jordan Belson variously drew inspiration from Fischinger’s mesh of geometry and melody and Lye’s erratic vibrant colors and pulsing rhythms. Smith’s early cinema was an attempt to translate music into color and shape. In 1950 he experimented in reversing this proposition by showing four films with a live jazz band. They responded to the images in a jam session as if to a leading instrument. The Whitneys developed a synthesizer which could simultaneously generate picture and sound. In their theoretical formulation of this synthesis, they saw their work as a reconciliation of the positions of Mondrian and Duchamp, the Neo- Platonic purist and the anti-aesthetic ironist. Belson eventually pushed his abstraction to the boundaries of representation where geometrical shapes mediate between suggestions of macro-cosmic and micro-cosmic imagery, for instance between an eye and galaxy or between a cluster of stars and swarm of bees.

Joseph Cornell, Rose Hobart (1936)

Another powerfully influential figure was the collagist and box maker Joseph Cornell. His films were rarely seen until the late 1960s, but they were very important to those who did manage to see them. His collage films of the late Thirties, Rose Hobart (ca. 1939) and the “Children’s Party” series, which he made by reediting other commercial films, are the masterpieces of their kind. Only Bruce Conner, who had not seen them, made collages of comparable intensity (A Movie [1958], Cosmic Ray [1962], Report [1967]) more than twenty years later. Larry Jordan assembled the “Children’s Party” series according to Cornell’s instructions in the late 1960s. His own graphic films testify to Cornell’s influence as a cutout collagist. Jordan brilliantly animated cutout figures against both fixed and shifting backdrops. Unlike the Polish filmmakers Lenica and Borowcyzk who practiced a similar technique, Jordan eschewed literalism. His collage films Hamfat Asar (1965), Gymnopedies (1965), Duo Concertantes (1964), Our Lady of the Sphere (1969), and Orb are allusive evocations of visionary ecstasies and terrors, organized through delicate rhythmic patterns of transformation, culminating in his great Sophie’s Place (1986)

Robert Breer, Fist Fight (1964)

Robert Breer’s animation evolved from flat work (Form Phases.1953) through a mixture of flat and shallow movements (cutouts alternating with crumpled papers, a mechanical mouse, bits of hand painting) in Recreation (1957) to a complex fusion of cartoon, collage, single frame changes, and live photography in Fist Fight (1964). In this film he also incorporated a sense of the filmmaking process when he lifted the camera off the animation stand and walked outside with it, filming his feet as he went, to take a shot of the sun. Breer has moved between poles of synthesis and purification. In Blazes (1961) he created a spectacular barrage of fast images by shuffling a series of calligraphic designs and filming them over and over in different random sequences. 66 (1966) explores the formal options of flat colored shapes in an animation that works with extremely fast changes and unusually long holds in an eccentric alternation. 69 (1969) presents a similar set of options, explored and fragmented, with a new element of illusory depth. In 70 (1970), he abandoned shape, and sprayed areas of white cards with colored dyes. The film animates these unbounded color areas, fusing the free texture of the hand-painted film with the control of the frame-by-frame animation. In Gulls and Buoys (1972) and Fuji (1974), the tension between animation and actual photography manifests for him a new form. Using a rotoscope technique, which ultimately dates back to Emile Cohl’s invention, Breer freely copies, in crayon and ink, isolated details of originally photographed material (seascape scenes, a Japanese train ride). However, unlike traditional rotoscopers, like Cohl and MacKay, Breer chose to emphasize elementary cinematic dynamics in the photography, by utilizing zoom shots, panning, hand-held camera, or by shooting from a train window, and incorporating single frame editing, and then allowing the freest possible hand strokes in the copying. The results are two cinematic iconic texts which mysteriously refer to an indexical original, “lost in translation.”

10.

Michael Snow’s Wavelength reformulated the central analogy of the American avant-garde: the camera as a model of cognition, by veering away from Brakhage’s attempt to translate the mechanical traces of the filmic process into optical and physiological functions. In Snow’s film the camera and its lens maintain their status as physical tools while allowing for an interpretation as a complex model for perception. This tension within the structure of metaphor may be what Snow meant by “the beauty and sadness of equivalence” in his note on the film for the Fourth International Experimental Film Festival Catalogue, where he wrote:

I was thinking of planning for a time monument in which the beauty and sadness of equivalence would be celebrated, thinking of trying to make a definitive statement of pure film space and time, balancing of ‘illusion’ and ‘fact’, all about seeing.

The film begins with an act of pure recording as if the camera were a completely passive tabula rasa instrument capable of preserving without distortion the impress of the exterior world. When people enter the loft carrying a bookcase, we hear them in synchronization. But soon after that, the natural sound is suspended and replaced by an artificially generated sine wave. On the visual track flashes of pure color, transitions to negative, slight superimpositions occur. Thus, both the sound and picture recording instruments begin to generate their own subject matter.

The problematics of “equivalence” include the alternation of day and night which occurs suddenly, twice in the film, without disturbing the relentless forward zoom. During the day the metaphorical link between the recording instrument (camera) and its object (the room, camera in Latin) was emphasized by changes in the intensity of the light: when the interior of the room darkened, the street scene outside became visible as if the windows were the camera lens. When the details within the loft received illumination, the exterior was burned out. At one point two people turn on a radio, which is an “equivalent” machine for gathering and translating sound waves. The Beatles “Strawberry Fields” is heard while the filmmaker responds by shooting through a pink filter.

The first transition to night is accompanied by the violent entry of an intruder who collapses on the floor. When night returns after another day passage, a woman enters, looks toward the body (we have zoomed past it by now) and telephones for help. After she leaves, her image repeats in flashes of black and white superimposition, as a ghostly reminder of the immediate past echoing within the room. From this point the zoom proceeds into a still photograph of waves pinned on the wall.

The next to last shot is another superimposition. The closeup of the waves is placed over an image which frames the photograph on the wall. The temporal movement of the zoom is thereby represented in the compound image.increasing the light on the photograph and fading out the framed image, Snow simulates the ultimate final movement in purely optical terms. In doing so, he reminds us that the zoom lens, unlike the moving camera, is static and represents virtual movement through the shifting optics of two lenses.

Michael Snow, Wavelength (1967)

The trajectory of Wavelength is initially mechanical, then a fusion of mechanism and the humanized presence of the filmmaker. But after the telephone call it provides a metaphor for a superhuman authority. At the middle stage, when the film-maker is co-present with this machine, Snow incorporates the strategies of Andy Warhol whose long takes of a man eating a mushroom (Eat), or of a building (Empire, 1965) and arbitrary zooming about in the room where someone is delivering a confessional monologue (much of The Chelsea Girls,1966), were themselves deflations of the metaphor of the camera as an eye or the mind.

Wavelength might be construed as a complex reaction to both the early and the late Warhol styles: the fixed camera and the impulsive zoom. Warhol’s unbudging camera was at first a radical dehumanization of the tactics of earlier filmmakers within the American avant-garde. He recognized, at least implicitly, that their way of making cinema was closely bound to the aesthetics of Abstract Expressionism which he had been dehumanizing in his paintings. His shift to filmmaking involved an attack on the same front in a different medium.

However, as he became involved in making cinema, Warhol seems to have found himself possessed by the work of Jack Smith. Under Smith’s influence, he slowly turned from the dialectically cold presentation of affective or at least private gestures (sleeping, getting a haircut, kissing, eating, etc.) to a cinema that focused on unstable psychologies and sadistically induced paroxisms of confession by its very refusal to be affected, as Stephen Koch has brilliantly analyzed in his book, Stargazer (1974).

A subsequent filmic structure investigating the nature of the zoom lens was Ernie Gehr’s Serene Velocity (1970). The spatial illusion that Gehr analyzes is so radically reduced that it can no longer contain any human activities. Gehr set up a camera in the corridor of an academic building and photographed, one frame at a time, changing the exposure for each frame, phrases four frames long. Between each of the phrases he changes the position of the zoom lens. In the course of the film, he moves from two close zoom positions in the middle of the lens’ range to its extremes of distance and closeness. The only articulation of temporal movement within the imagery of the film is the gradual breaking of dawn, seen in the brightening of a window in a door at the end of the corridor in the last minutes of the film. For a viewer, the film describes a rhythmic crescendo; for although neither the camera position, nor the spatial field before it, changes, the illusionary movement of the zoom, from what appears to be a pulsing vibration, to a strenuous push-pull effect, creates increasingly greater optical tension and the concomitant effect of gradually destroying the spatial illusion by emphasizing the ort orthogonals of the corridor as a two-dimensional grid with each increment of the zoom ratio.

Ernie Gehr, Serene Velocity (1970)

In his subsequent film Still, (1971), it is the camera position that remains still while the ostensibly temporal difference between scenes shot from the same position, in clusters of superimposition, provides the structure of the film. Furthermore, by varying the light intensity of different layers of superimposition, Gehr can render the people and vehicles which pass before the optically “solid” cityscape with varying degrees of transparency. Thus, the temporal flux which introduces differences in color and horizontal movements (and occasional diagonals as people cross the street) as ad hoc ephemera in a relatively shallow theatre is limited by the frontal mass of building facades at a right angle to the camera. A version of the same principle can be seen in Ken Jacobs’ Soft Rain (1969). There the filmmaker shoots out a window over low rooftops, onto a city street with cars and people passing. A piece of black paper, hung in front of the lens, occupies an ambiguous optical space, as if it might be a window shade. The projecting wall of a building next to the Serene Velocity rooftops forms a perfect line from one edge of the frame to its geometrical center, but the eccentric angle of its photography calls attention to the very disparity between a geometrical and an illusionary reading of the space. The title of the film directs our attention to a drizzle on the threshold of perceptibility which becomes, according to the film-maker’s intention, confused with the grain of the film. Finally, a temporal pattern is manifested by the exact repetition of the same roll of film three times. However, the viewer must perform a deliberate act of memorizing arbitrary sequences of human and automobile movements, after the first roll has ended, to determine for certain whether or not the three rolls are indeed a repetition or three different takes of the same scene. In both Still and Soft Rain the absence of camera movement and the arbitrary patterns of movement help to establish an authority for the exterior scenes which is only gradually undermined when the active understanding of the viewer is engaged in spotting and following-up clues embedded in the image. The unusually long duration of the shot (within the standards of the dominant cinema contributes to engaging the viewer’s understanding by disengaging his sensual involvement with the illusionary image.

11.

Brakhage’s critique of the tripod has been part of his attack on the very resistance of filmic materials to conform to the subtleties of the representation of cognition. In Metaphors on Vision he wrote:

And here, somewhere, we have an eye capable of any imagining. And then we have the camera eye, its lenses grounded to achieve 19th century Western compositional perspective (as best exemplified by the 19th century architectural conglomeration of details of the “classic” ruin) in bending the light and limiting the frame of the image just so, its standard camera and projector speed for recording movement geared to the feeling of the ideal slow Viennese waltz, and even its tripod head, being the neck it swings on, balled with bearings to permit it that Les Sylphides motion (ideal to the contemplative romantic) and virtually restricted to horizontal and vertical movements (pillars and horizon lines) a diagonal requiring a major adjustment, its lenses coated or provided with filters, its light meters balanced, and its color film manufactured, to produce that picture post card effect (salon painting) exemplified by those oh so blue skies and peachy skins.