The Dissolution of Marxist Humanism

In 1906, Benedetto Croce, in his What is Living and What is Dead of the Philosophy of Hegel, inquired about philosophy in a new way. Instead of asking what is true and what false in the established idiom of philosophy, he posed the question in a way that was immediately historical: what was true might have become false and what was false might have become true. It asked about the here and now of philosophy not its eternal content. To be sure, this historical reference already existed in Hegel insofar as truth was understood to come into being but it was also seen to culminate in logic—that is to say, a truth that encapsulated history even while emerging from it. Croce implicitly asserted the incompatibility of logic and history. His verdict was that what is dead amounted to Friedrich Engels’ reduction of philosophy to the logic and dialectic of the positive sciences. What is living is the idea of a concrete philosophy, “a form of mind, which should be mobile as the movement of the real.”[1] For the mobility of thought to catch the movement of reality it must be willing to take leave, not only of the falsehoods of the past, but of its truths.

Given that it is now more than a half-century since the iconic year 1968, a reflection on the philosophical situation of that time, and our distance from it, seems in order.[2] Though 1968 is no longer simply a year but a name for what is known as “the Sixties,” a time whose myth still survives in our cultural history. Philosophy in that time was part and parcel of the international phenomenon of the Sixties in which decolonisation, the New Left, youth politics, the fight against institutional racism, women’s liberation, anti-war activism, cultural radicalism, and many more strands were woven together.

The philosophy of the Sixties which I want to define is not the thought of one situated person, nor a group, even less a party. It is a discursive space within which philosophies oriented to their time operate.a discursive space I mean a realm in which arguments and explications can be made, which is structured in a certain form, but which remains as a background to explicit philosophical articulations and debates between them. The interplay between more-or-less structured background assumptions and explicit articulations means that, while there are certainly characteristic philosophies of the time, those which are less characteristic are subliminally required to address those which are dominant. While I will explain the discursive space of philosophical discourse in the Sixties with reference to influential figures, the discursive space itself is a more encompassing phenomenon whose full explication would require a much more detailed investigation.[3] One’s own struggle for truth operates within such a discursive space and in this way we not only are born into a time but struggle to become true children of our time and thus perhaps adults who may define their time and play a role in shaping it.

Without further preamble, I want to assert that the dominant philosophy of the Sixties was Marxist humanism or existential Marxism. I mean no distinction between these two terms that were both very much in evidence at the time. The interplay between three key terms define its discursive space: a certain understanding of Marx, existentialism (primarily of the French variety), and humanism—a term with a long history that took on a quite specific meaning. Marxist humanism began in philosophical exchanges between Western and Eastern Europe and became a world phenomenon dominating the “discourse” of the times. What is living and what is dead in Marxist humanism? This question may be broken into three parts: 1] what was it? 2] how and why did it dissolve? and 3] what blindspots in Marxist humanism can be retrospectively discovered?

1. What was Marxist Humanism?

The humanist reading of Marx can be dated from Erich Fromm’s Marx’s Concept of Man which appeared in 1961 and went through sixteen printings by 1971. Fromm convinced T.B. Bottomore to translate Marx’s 1844 Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts into English for his volume.[4] The manuscripts had been available in German since 1932 but had not made inroad into English-language discussions. Even in Europe, the Second World War had interrupted the continuity of Marxist theory, so that the 1960s reading occurred largely independently of former discussions. Bottomore also published Marx’s Early Writings, which included the Manuscripts, in a separate 1963 edition. The foreword by Fromm emphasised that “Marx was a humanist, for whom man’s freedom, dignity, and activity were the basic premises of the ‘good society’.”[5] Similarly, his introductory interpretation in Marx’s Concept of Man emphasised that “Marx’s central criticism of capitalism is not the injustice in the distribution of wealth; it is the perversion of labor into forced, alienated, meaningless labour, hence the transformation of man into a ‘crippled monstrosity’.”[6] The appropriation of Marx in Marxist humanism was the conception of the whole human being alienated by capitalism from the human essence and capable of recovering that essence through the activity of creative labour. This conception allowed a dual critique of the Cold War: consumerism as alienating in the West and the subjection of the individual by the state in the Soviet bloc.[7] In 1965, Fromm edited a volume of essays by 35 contributors from both East and West that showed that socialist humanism had become not only a philosophical tendency but a rallying cry. As he put it in the introduction, “socialist Humanism is no longer the concern of a few dispersed intellectuals, but a movement to be found throughout the world.”[8] The hierarchical control of the labour process, and the subjection of the individual worker to the factory, appeared no different on either side. Marxist humanism aimed to avoid the confrontation of East and West through a return to the creative individual in search of non-alienated work and social relations.

This humanist interpretation was so much on the agenda that when Louis Althusser responded to the French translation of the Manuscripts in the Communist journal La Pensée in 1962 he attempted to draw a strict line between the early and late Marx, relegating the early work to a surpassed period of political ideology that was left unpublished for good reason.[9] We can see this also in Fromm’s interpretation of Freud with the concept of alienation that allowed him to see Marx and Freud as parallel thinkers: through an analysis of the external factors that condition and limit human beings, the capacity for freedom and conscious action can be revivified and returned to the humanist subject. As he said, “by being driven by forces unknown to him, man is not free. He can attain freedom (and health) only by becoming aware of these motivating forces, that is, of reality, and thus he can become the master of his life (within the limitations of reality) rather than the slave of blind forces.”[10] Both Marx and Freud were interpreted as pointing to barriers that need to be removed for the free, self-determining human subject to emerge.

Humanist Marxism was the basis for critique of alienation in both West and East not only in the West. The Praxis School, based in Zagreb and Belgrade, gathering annually at the Korčula Summer School and expressing itself in the international journal Praxis, developed a critique of Soviet authoritarianism in dialogue with critical voices in the West. Gajo Petrović emphasised that Marx’s humanism was a philosophy of praxisand that action requires an orientation to the future, so that humanism is oriented to “historically created human possibilities.”[11] Ivan Svitak elaborated a certain convergence thesis between East and West, suggesting that the industrial maturity of the Soviet Union had led to its adoption of “a modified version of the American way of life” by making a high level of consumption its main priority.[12] Future possibility thus seemed to be aligned with a critique of consumer society and a recovery of the creative activity of social individuals. A major point of orientation for this was the current state of industrial self-management in Yugoslavia. Without overlooking its difficulties, self-management within the more independent countries of state socialism provided a starting-point for the development of industrial democracy as the form of work organisation that would fit with Marxist humanism. Mihailo Marković argued that the “natural extension and integration of various bodies of self-management into a whole would be a practical negation of the state and would put an end to professional politics.”[13] While the rejection of the authoritarian state was more a matter of immediate reaction in the West, in the East it provoked analysis of the failure of state socialism and an attempt to recover a humanist Marx from official state ideology. The fact that private property had already been abolished in Soviet-style societies showed that social revolution had to go beyond it. As Marković said, “the essential characteristic of revolution is a radical transformation of the essential internal limit of a certain social formation.”[14]

It was the goal of Marxist humanism to mark the limit of consumer society in its twin forms of capitalism and state socialism and to propose a future form of active individual participation in authentic social life grounded in work relations and extending throughout all institutions. One aspect of this approach that needed especial underlining was the role of the individual due to the neglect or suppression of the individual in all current forms of Marxism. In this respect existentialism, especially but not exclusively of the French variety, came to play an essential supplementary role to the rediscovery of the early Marx. Fromm, in support of his claim that “Marx’s aim [was] the development of the human personality,” referred to his philosophy as humanist existentialism.[15] The Czech philosopher Karel Kosík argued that “the pseudoconcrete of the alienated everyday world is destroyed through estrangement, through existential modification, and through revolutionary transformation.”[16] In his critique of orthodox Marxism’s one-sided focus on structural change, Kosík suggested that a prior individual act turns merely accepted reality into an active attempt to live authentically. Without such an existential modification the subsumption of the individual to social structures would persist after revolutionary change. Kosík utilised his appropriation of phenomenology and existentialism to show that philosophy is an opening of human reality toward being. Whereas in contemporary society “man is walled in in his socialness”—it is seen as a limitation—Marx’s philosophy of praxis is oriented to “the process of forming a socio-human reality as well as man’s openness toward being and toward the truth of objects.”[17]Existentialism came to the aid of Marxism in order to revivify its relation to philosophy and to understand philosophy as an active stance in the world.

The key figure for the existentialism of the period was Jean-Paul Sartre and its ground was provided by Sartre’s 1936 text Transcendence of the Ego in which he criticized the phenomenological philosophy of Edmund Husserl. Husserl is one of the most significant figures in 20th century philosophy whose influence went far beyond those who remained faithful to his ideas. Husserl had distinguished between the concrete, or individual human, ego and the transcendental ego. The transcendental ego emerged through what was called a transcendental reduction in which the question of the reality of the world was neither affirmed nor denied but simply set aside. This allowed for the human world as a world of meaning to emerge and become systematically investigated. In philosophical language, transcendental refers not to the immediate contents of experience but to the conditions or grounds which allow those contents to appear. Phenomenology, in Husserl’s terms, would investigate the meaning of events in the human world in relation to the ultimate source of such meanings. This duality was expressed in terms of that between the concrete, or socio-historical, individual subject and the transcendental ego which is anonymous, non-individual, and stands outside of history.

In Husserl’s view, the transcendental ego was a necessary aspect of ordinary perception insofar as ordinary perception presupposes a temporal structure, an intentional relation between perception and object perceived, a world including both perceiver and perceived, etc. None of these are constructed by the individual subject. He spoke of these transcendental features of experience as belonging to a transcendental ego and it is this with which Sartre took issue. Sartre argued that whatever might be called transcendental is not an ego but a pure impersonal spontaneity with no egoic features.[18] The consequence was that

The phenomenologists have plunged man back into the world; they have given full measure to man’s agonies and also to his rebellions. Unfortunately, as long as the I remains a structure of absolute consciousness, one will still be able to reproach phenomenology for being an escapist doctrine … It seems to us that this reproach no longer has any justification if one makes me an existent, strictly contemporaneous with the world, whose existence has the same essential characteristics as the world.[19]

Sartre’s rejection of the transcendental ego was his point of departure from Husserlian phenomenology and his point of entry into the existential philosophy that he would elaborate in Being and Nothingness. A subject that was thoroughly worldly could not seek its authenticity in ascending beyond immediate historical conditions but only through confronting them on the basis of its own responsibility. This emphasis on individual choice and freedom was the acid bath out of which humanist Marxism could emerge without any remaining stain linking it to orthodox, authoritarian, state-centred, Soviet Marxism.making meaning dependent on individual free choice Sartre seemed to totter on a slippery slope toward egotism or even solipsism. However, very much like Kosík, he argued that this did not mean an enclosure within the individual but rather the individual as the necessary basis for openness to authentic social commitment. Since the choice for resistance against Nazi occupation was for Sartre and his readers a recent memory, it could be in a certain sense reprised during the 1960s as a free choice for the Extra-Parliamentary Opposition. To this extent, it was as much anti-authoritarian and anarchist as Marxist—as the practice of the New Left often was. As Sartre said in the 1945 lecture “Existentialism Is a Humanism”

When we say that man chooses himself, we do mean that every one of us must choose himself; but by that we also mean that in choosing for himself he chooses for all men. … To choose between this or that is at the same time to affirm the value of that which is chosen; for we are unable ever to choose the worse. What we choose is always the better; and nothing can be better for us unless it is better for all.[20]

In 1948, essentially contemporaneous with Sartre’s public lecture, Herbert Marcuse had criticized Sartre’s existentialism of Being and Nothingness as a positivist tract which lost the transcendence of the given world that it was the job of philosophy to furnish.[21] However, when he republished the essay in 1972, Marcuse changed his tune:

The basic existentialist concept is rescued through the consciousness which declares war on this reality—in the knowledge that reality will remain the victor. For how long? This question, which has no answer, does not alter the validity of the position which is today the only possible one for the thinking person.[22]

In this way existentialist choice became fundamental to Marxist humanism: a subject fully immersed in the world but nevertheless with the freedom to choose to revolt could enter into the historical analysis and revolutionary transformation proposed by Marxism with sacrifice of neither individual value nor responsibility.

This humanist subject was taken to subtend all of the different forms of oppression and exploitation. In Brazil, Paulo Freire began from this point to develop further Sartre’s critique of education as a form of digestion in which students are passively fed knowledge by professors.[23] It entered into Simone de Beauvoir’s examination of woman’s situation and possibilities. It allowed Sartre to declare in his introduction to Frantz Fanon’s Wretched of the Earth that “the Third World finds itself and speaks to itself in this voice.”[24] To be sure, the critique of consumerism co-existed somewhat uneasily with the critique of colonialism, but they were held together by the concept of human liberation as the development of human capacities in a social form. Kwame Nkrumah emphasised the necessity for a new socialist philosophy that could synthesise the humanist basis of traditional African society with Islamic and Euro-Christian humanism.[25] In all of these versions the humanist subject “man” was taken as a unity that could be explicated whose necessary explication through differences of sex, gender, race, centre/periphery, etc. did not undermine a philosophical expression that could address all the different forms of oppression and exploitation.

Existential choice filled the hole brought about in Marxism, of whatever kind, by the change in the class structure and world order since Marx’s time. The existential decision of the individual taken alone in free choice but in favour of the freedom of all appeared to be able to hold together decolonisation, women’s liberation, the socialism of the working class, and the search for individual meaning, in one great theory of human liberation. Perhaps the most significant index of this is that Herbert Marcuse’s influential One-Dimensional Man—a book arguably the most characteristic of the 1960s—could hover without resolution between the expectation that advanced industrial society could contain its contradictions and that an explosive break could occur.[26]Marcuse presented a mountain of evidence for containment yet clearly appealed to the reader to follow him in enacting the moment of freedom in its ungrounded leap from enclosure within a given reality toward a commitment to making a new world.

The 1960s was an era of decolonisation in what was then referred to as the Third World alongside an internal radicalism within the East-West division of the industrialised world. The former was oriented towards national liberation movements that aimed to end imperialist exploitation and cultural subjugation. The latter was oriented to a critique of advanced consumerism in the West and the aspiration to match or surpass Western consumerism in the East. It was the capitulation of both the social-democratic left and Soviet Marxism to a consumerist model that allowed the New Left to synthesise a critique of consumerism with support for national liberation movements in the Third World. It was necessary to address the Cold War division of the world into East and West, the welfare state compromise in the West that raised the standard of living of the working class, the family wage that sent women back to the domestic sphere, the rise of consumer capitalism, institutionalised racism and decolonisation in the so-called Third World. These events overlapped and reinforced each other in many ways. As Kwame Nkrumah pointed out:

In the industrially more developed countries, capitalism, far from disappearing, became infinitely stronger. This strength was only achieved by the sacrifice of two principles which had inspired early capitalism, namely the subjugation of the working classes within each individual country and the exclusion of the State from any say in the control of capitalist enterprise.abandoning these two principles and substituting for them ‘welfare states’ based on high working-class living standards and on a State-regulated capitalism at home, the developed countries succeeded in exporting their internal problem and transferring the conflict between rich and poor from the national to the international stage.[27]

In the sense that it spoke to the integrated form of these historical and political realities, Marxist humanism was a philosophy both of that time and for that time. It both expressed the common situation and provided reference points for transforming that situation—even though the standpoint of salient groups within it were different. What we are lacking these days is precisely a common philosophy that could articulate the different standpoints of the various groups situated within the world-system.

The background of this radicalism in the West was the welfare state compromise that followed the Second World War. The working class had been brought into the system through a social welfare package including unemployment insurance, subsidised higher education, and progressive wage legislation. In the current neo-liberal age, after decades of right-wing attacks on even the mildest forms of social welfare, it is surprising to recall to what extent the gains of social democracy and the welfare state were taken for granted at that time. The main reason was that social democrats had bought into Cold War ideology and supported the war in Vietnam as well as benefitting from imperialist exploitation. Radical movements assumed this welfare state background and fought for its extension to still-unfranchised groups. Thus, the critique of consumerism co-existed somewhat uneasily with the aim of establishing a decent standard of living in the Third World. They were held together by the aim of a different model of development that would both spread material wealth more equally and also develop cooperative work and social relations. In its critical focus it was an era of anti-imperialism. While Marxist theory pointed to the industrial working class as the political actor, the many movements developed critiques of this focus based on a model of national liberation. Many retrospective analyses of the Sixties have interpreted student and youth radicalism in the West as primarily a reform movement aimed at developing cultural alternatives and less hierarchical socio-political relations. While there is some merit to this as an evaluation of the upshot of such movements, it ignores entirely the central role of national liberation movements as the spiritual centre of the idea of new social relations. It was fundamentally an anti-imperialist period and even many political issues within the advanced West were seen in these terms—such as Québec liberation, women’s liberation, Black liberation (especially in the U.S.A.), Red Power, etc. In our time only the remnants of a welfare state survive. However, the capitalist economy is no longer held sufficiently within the bounds of the nation-state and the background political-economic assumptions of the discourse of Marxist humanism no longer obtain.

2. The Dissolution of Humanist Marxism

I have suggested that the philosophy of the Sixties should be understood as a compelling discursive space and not as a specific doctrine. Now I want to focus on how certain problematic aspects of Marxist humanism provoked subsequent reactions and developments that led to its dissolution. Again using the terminology of popular philosophical discourse, these developments can be designated as “post-structuralism” and explained with reference to several highly influential works of Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida. Parenthetically, they also marked in Anglophone discourse a shift in the primary reference from German to French philosophy. Dissolution began already within the heyday of Marxist humanism.

Foucault’s early masterpiece The Order of Things: An Archeology of the Human Sciences appeared in French in 1966 and English in 1970. One of its major theses was that the modern attempt to understand empirical human reality through the human sciences entailed a doubling of the subject. Humanity appeared as the object of the various sciences that, at least in principle, would add up to an eventually complete knowledge of empirical humans but also appeared as the subject of knowledge—a transcendental subject. To be sure, this in itself was not an original thesis. Notably it had appeared in Edmund Husserl’s phenomenology, especially in the later work The Crisis of the European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology. Foucault’s specific thesis is that this “empirico-transcendental doublet” could not be maintained as two separate dimensions but, through the central concept of critique, depends on the idea of a true scientific discourse that cannot localized as either transcendental or empirical. “In fact, it is not so much of an alternative as a fluctuation inherent in all analysis, which brings out the value of the empirical at the transcendental level.”[28] The necessary fluctuation in the doubling of man (sic) means that the radical question is whether “man” exists at all or, as the famous last sentence of the book muses, classical modern thought might end such that “man would be erased, like a face drawn in sand at the edge of the sea.”[29]

Yet despite this powerful first salvo at the central, ambiguous concept of man at the centre of Marxist humanism, this text was too difficult to have a widespread effect. The clearest and most influential rejection of Marxist humanism came in volume 1 of Michel Foucault’s History of Sexuality, which appeared in 1976 and was translated into English two years later. He identified what he called the “repressive hypothesis” that put into parallel the repression of sexuality with the rise of capitalism due to the incompatibility of pleasure with work. Against this, he asserted that the idea of sex as repressed feeds a facile pose of transgression, characterizing

a society which has been loudly castigating itself for its hypocrisy for more than a century, which speaks verbosely of its own silence, takes great pains to relate in detail the things it does not say, denounces the powers it exercises, and promises to liberate itself from the very laws that have made it function.[30]

Foucault’s own programme was, in contrast, to investigate the productive power of discourses about sex and, beyond sex, this idea of the productivity of discourse in constituting subjectivities has become the general figure of social analysis since then. From this point of view, Freud, instead of being a great liberator, became the producer of discourses that constituted constraining subjectivities. Marx was treated more carefully, mentioned only once in Foucault’s text to show that the bourgeoisie took a long time to acknowledge the bodies and sex of the proletariat.[31] However, the direct reversal of the form of critique suggested that “it is a ruse to make prohibition into the basic and constitutive element from which one would be able to write the history of what has been said concerning sex starting from the modern epoch.”[32] Since then, Foucault and his analysis of power as productive rather than repressive has become ubiquitous in Anglophone social sciences. We may note that, if this approach were to be applied to Marx, it would suggest that it is also a ruse to claim that labour in its capitalist form is a prohibition, a containment, or a loss of the worker’s truly human powers. Perhaps this might explain why Marx has largely disappeared from the writings of those who begin from the notion of discursive productivity.

Foucault’s reversal of the model of critique was elaborated in direct opposition to the Marxist humanist figure of alienation. Whether it applied very well to Freud or Marx is open to debate, but it certainly applied to the synthesis of Marx and Freud through the concept of alienation that immediately preceded it. It leads us to question the humanist premise expressed succinctly in Fromm’s phrase that I mentioned previously, that one can “attain freedom (and health) only by becoming aware of these motivating forces [and] become the master of his life (within the limitations of reality) rather than the slave of blind forces.”[33] Everything at issue depends on this small, almost-parenthetical insert “within the limitations of reality.” If there are limits to being a master rather than a slave, how do we know these limits? Are there elements of human being that are not captured adequately within the alternative of master or slave? If there is no original human subject, and therefore no human essence, how can social revolution claim to establish human creative powers in an authentic social form?

The interventions by Derrida show a similar oscillation between philosophical and popular dimensions. In 1966 he gave a lecture at the famous John Hopkins conference on The Language of Criticism and the Sciences of Man which was ostensibly to be about French structuralism. However, Derrida’s talk, later published in the widely read book of conference papers, rather announced the end of structuralism, specifically centring on a critique of Levi-Strauss. Arguing that every structure requires a centre that both stands above the structure and organizes its dispersal, he elaborated his deconstruction of the empirico-transcendental doublet. The problematic of language, which determines structuralism, entered “when everything became a system where the central signified, the original or transcendental signified, is never absolutely present outside a system of differences.”[34] The superabundance, or apparently transcendental character, of the centre should thus be understood as a supplement of finitude or empirical reality. It derives from a lack within finite reality itself. The end of modern knowledge would be in the abandonment of any humanist centre “in the face of the as yet unnameable which is proclaiming itself.”[35]

Another lecture in 1968 solidified Derrida’s role in the dissolution of humanism. “The Ends of Man” begins with a long reflection on the purpose of international philosophical meetings and the meaning of categorizing philosophy by nation, in the course of which he referred to the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., Vietnam and the Paris university upheavals. While these references were short and rather indefinite, he claimed that “these feelings seem to me to belong by right to the essential domain and the general problematics facing this conference” giving them a sharp contemporary historical reference.[36] To address the question of how France stands with the question of man, he analyzed the three German thinkers, reaction to whom had largely defined recent French thought: Hegel, Husserl, Heidegger. His thesis is that the French reception of these thinkers, all of whom were taken to be critics of anthropologism, was still a humanist critique and thus that current French philosophy “seems … to amalgamate Hegel, Husserl, and in a more diffuse and ambiguous manner, Heidegger, with the old humanist metaphysics.”[37] The current situation thus opens two possibilities: either to attempt a deconstruction which repeats the founding gestures of the metaphysics of presence or to “decide to change ground, in a discontinuous and eruptive manner, by stepping abruptly outside and by affirming absolute rupture and difference.”[38] It is of course the latter alternative with which Derrida identified himself and which he pursued through an application of Heidegger’s thesis of a metaphysics of presence infecting philosophy since Plato to current French philosophy marking it as insufficiently anti-humanist. The undeveloped references to the contemporary politics of the 1960s served to colour this philosophical thesis with a political, or apparently political, radicalism.

These interventions by Foucault and Derrida in the 1960s began an effective puncture of the predominant discourse of Marxist humanism. At the time they occurred in relatively esoteric philosophical contexts but over time their thesis of the end, or death, of “man” became accepted as if proven beyond doubt, primarily through its popularization in Foucault’s History of Sexuality, Volume 1. Recall that my discussion is oriented to the shift in a dominant philosophical discourse, not with the intrinsic validity of the texts and their arguments themselves. In sum, they served to displace the central concept of “man” that anchored Marxist humanism and ushered in a new discourse, often called post-structuralism, which did not have the generally compelling role of Marxist humanism. Indeed, since that time philosophical discourse has become much more plural and a replacement is not on the horizon.

3. Blindspots in Marxist Humanism

I have up to now focussed on the key central term “man” through which Marxist humanism was articulated and which was criticized by the emergent post-structuralist discourse. This criticism opened up its fractioning by race, sex, gender, and other social positions and undermined the unity of the theory of liberation proposed by Marxist humanism. While we can mark the dissolution of humanist Marxism clearly enough, it does not suffice to answer the question of how its emancipatory role might be transformed and renewed in the light of new political and philosophical challenges. Indeed, the outright rejection of Marxist humanism would rather seem to motivate a wholescale abandonment of a philosophy of human liberation—or at least any unified or general theory.[39] Let us now undertake a more detailed examination of specific features of humanist Marxism which have demanded re-evaluation by taking each of its three parts in turn: Marxism, humanism, existentialism.

Marxism was understood in the terms of Marx’s early critique of capitalist society such that the later, detailed, and theoretically rich critique of political economy in Capital was interpreted as if it added nothing significant to the concept of alienation.[40] While in the 1960s Marxist humanism and Althusserian structuralism were viewed as an either-or decision between the early and late Marx, it is now possible to see that the late critique of political economy is a development of the early alienation theory and therefore to seek a precise definition of what aspects are significantly improved. I want to make just two observations about this advance.

When Marx returns in Capital to the dialectical relation between humanity and nature that he described initially in his early work, he significantly adds technology as the mediation between humanity and nature.[41]He describes the transhistorical, or ontological, features of labour in its components of work, the natural material worked upon, and the instruments (or technology) used in work. Technology is the specifically human aspect of labour which is both a product of a previous labour process and operative in living labour. The category of technology is interestingly elastic. Marx says,

In a wider sense we may include among the instruments of labour … all the objective conditions necessary for carrying on the labour process. … [T]he earth itself is a universal instrument of this kind, for it provides the worker with the ground beneath his feet and a ‘field of employment’ for his own particular process. Instruments of this kind, which have already been mediated through past labour, include workshops, canals, etc.[42]

This wider sense of technology thus includes the earth as it has been modified by previous human activity as well as the earth unmodified as a ‘ground’ insofar as it is a necessary condition for living labour—such as water, air, gravity, etc. In this sense, Marx includes what Hegel calls first and second nature as aspects of technology. Technology, even “in a wider sense,” seems a strange name for this. We would now likely call it the environment, or even ecology, as well as the built environment.introducing this wider sense of technology Marx aims at a sense of nature, or environment, which may well be altered by human activity but has not been in its totality the object of human activity. Marx did not draw this conclusion, but it is implied by his expanded conception of technology. Nature and the built environment are the cumulative, unintended upshot of previous labour that supports and conditions subsequent living labour. Since human activity aims at specific goals, this cumulative historical totality of original nature and built environment modified through technology cannot be itself understood as an intended product of human action. In this sense, Marx himself seems to me not guilty of the Prometheanism of the domination of nature with which he is often charged but which does apply to the dominant official versions of Marxism. The philosophical issue becomes one of the initial natural ecology, its transformation by technology into the built environment, and the surplus labour through which human activity exceeds simple reproduction and allows the development of technology that alters the character of the labour process historically.

Interestingly, while in Volume One Marx utilises the surplus productivity of labour to explain the surplus value that is appropriated from the labour process by the capitalist, he does not explain its origin until the discussion of ground rent in Volume Three. There it becomes apparent that the surplus productivity of labour in the end rests on a natural fact that is more evident in agricultural labour in the direct interchange between human labour and nature.

The natural basis of surplus-labour in general, that is, a natural prerequisite without which such labour cannot be performed, is that Nature must supply—in the form of animal or vegetable products of the land, in fisheries, etc.—the necessary means of subsistence under conditions of an expenditure of labour which does not consume the entire working day. This natural productivity of agricultural labour (which includes here the labour of simple gathering, hunting, fishing, and cattle-raising) is the basis of all surplus-labour, as all labour is primarily and initially directed toward the appropriation and production of food.[43]

We might call this natural fact that makes surplus productivity possible natural fecundity. It inheres in the natural ecology prior to human intervention through technology even though it can be multiplied by such intervention. In this sense, the late Marx grounds the dialectic of humanity and nature in the fecundity of natural ecology.

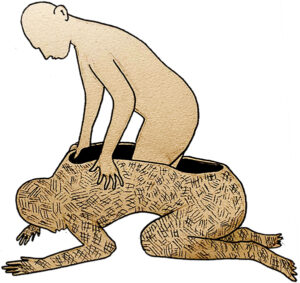

While the inflection humanist Marxism meant a preference for the early over the late work, the inflection Marxist humanism meant a renewal of the humanist tradition through its extension into the sphere of work and its structures of exploitation. Marx’s early theory of alienation allowed this extension of humanism to be understood as a loss and subsequent recovery of the true human subject. The alienation model is originally a trinitarian structure of an authentic internality, an externalisation, and then a new internalisation that incorporates some of the features of the externalisation but returns them to an internal coherence. Of course, this model has been complicated in many of its applications, but the basic structure persists: self-other-expanded selfhood. This model is what allowed Marxist humanism to assume the human subject as its starting and terminal points and thereby launch critiques of alienation in the current world. It also grounds a parallelism between individual and social critiques, the very parallelism that allowed Fromm and others to treat Marxist and Freudian critiques as in principle identical, so that the idea of a return to authenticity from social alienation and individual neurosis governed the practice of critique.

Placing the humanist subject as the point of authentic origin, the constitution of the subject as such was not a matter for concern. For that reason, the ethical basis and goal of Marxist humanism seemed to be guaranteed. Since then we have become much more conscious of the formation of the subject as a socio-psychological process such that the pluralities of gender, race, etc. are not seen simply as alienations that must be cast off, but as constructions that pluralise the notion of the human subject itself. These days there is a widespread tendency, which parallels that of the invocation of Foucault or Derrida, to quote Althusser’s notion of the interpellated subject as if it was characteristic of the Sixties. But if the subject is structurally generated, how can it remain ethically important? Once we understand the individual as constituted through, and not simply alienated by, social processes, the sense in which one could return to an authentic self becomes quite uncertain. As a consequence, we often seem to have lost that sense of human universality in an ethical sense that animated Marxist humanism. Our task now, I would suggest, is to understand the plural constitution of subjectivities alongside an ethical universality.

This is especially significant for the interpretation of Freud as a humanist. To be sure, Freudian analysis aims to free the subject in the sense that neuroses would no longer dominate action in an automatic sense, as Fromm claimed. But there is no sense in which the Freudian unconscious can ever be made fully conscious—so that the constitution of the subject means that it could never recover itself in a full appropriation of its own ground. A similar point can be made in reference to Marković’s understanding of revolution as transgressing the internal limits of a social formation. It seems rather incredible that such limits could be made fully conscious within the social formation in a manner that would allow it to be actively transformed such as to breach those limits and become a new social form in which what those limits conceal could be made evident. A social form, and the transition between social forms, is not likely to become transparent in that sense. The point is that the Marxist understanding of humanism through the alienation story over-simplified greatly the issue of how the human individual is constructed by forces that the individual cannot control—not even in principle—and consequently the issue of how the limitations of a social order can be made apparent within it. And, even more, how such limiting perceptions and understandings might be made the object of revolutionary action.

This same issue appears within the existentialist inflection which collapsed what Husserl called the transcendental and empirical egos. For Husserl, worldly intentional meaning in its inherently dual structure of perceiver-perceived, acted-acted upon, or thinker-object of thought, meant that, in order to reveal and understand this structure, a perspective that could get beneath it to its origin was necessary. He called this the transcendental ego. I won’t go into this now, but it is not at all clear why Husserl thought that transcendental reflection had the structure of an ego—especially since it encompassed both perceiver and perceived, etc. But there is no doubt that calling it an ego made it seem as if it was an ego in the same, or similar, sense in which a concrete ego, or an individual person, is an ego. Husserl called this a “paradox of human subjectivity,” that of being the subject of all possible experience of the world and at the same time being an object within the world. While he termed this an “equivocation” he nevertheless thought it an essential, or inevitable, one—which it must be, if the transcendental field is in some sense an ego.[44] Thus, there was a valid point to be made when Sartre argued that the transcendental ego in Husserl’s sense was a flight from one’s concrete embeddedness in the world of action. As Husserl said, the transcendental ego is immortal, is not born and does not die.[45] But there is no reason to reject transcendentality itself as an inquiry into the grounds of meaning that constitute the correlation between the concrete subject and its perceptions, actions, and thoughts. Indeed, unless we are to be left imprisoned inside the actually given social world—which is where Sartre leaves us—some transcendental inquiry into the grounds and presuppositions of a meaningful world must be possible. As Herbert Marcuse never ceased to emphasise, it is philosophy that, due to its transcendence of the existing world, preserves the conceptual basis for the transformation of social reality.[46]In short, Husserl’s equivocation led to Sartre’s flattening, and Sartre’s flattening leads to both an appreciation of the concrete world as the only world for existing humans and the exclusion of sufficient inquiry into the grounds of this world to be able to formulate the project of its overcoming—except as the fiat of an individual choice.

Several strands of our reflection on the dissolution of Marxist humanism converge at this point: how to perceive and act upon the essential internal limit of a certain social formation; the humanist subject as constituted and therefore not a point of origin but still an ethical goal; the too-simple parallelism between the individual and social subject through the paradigm of alienation. Indeed, Husserl himself noted that the resolution of the paradox of subjectivity in a manner that would remove the equivocation could occur through addressing the constitution of intersubjectivity—rather than moving directly from the individual I to the social subject, one would need to pass through all the mediations that assemble individuals into groups, and from there to a universal subject that could ground an ethical humanism. Thus, there emerges a crucial differencebetween individual subjectivity and social change—a difference requiring a great deal of analysis and action—which was covered over and made to seem self-evident by simply calling it an existential choice. One final aspect of this conflation of individual and social dimensions should be mentioned: Marx’s paradigm of alienation in the 1844 Manuscripts shunted aside the inevitability of individual death as without interest, precisely because it didn’t fit into the definition of human being as species-being and thus universal (Gattungswesen).[47] The humanist nterpretation of existentialism through Sartre’s “commitment” rather than Heidegger’s “being-toward-death,” as well as the loss of the tragic dimension of Freudian psychoanalysis, thus make perfect sense. Though the dissolution was no doubt motivated and perhaps inevitable, one may be forgiven for thinking that something was lost in the process.

4. What Might be a Philosophy for Our Time?

Thus one might understand the original significance of Marxist humanism, its dissolution, and some internal reasons for that dissolution. Recall that I have suggested that the emphasis on the early Marx overlooked the role of technology and the built environment in establishing the historical dynamic between humans and nature. Nowadays, the relationship between Marx’s mature critique of capitalism and technology, the built environment, and natural ecology is a pressing issue that has been addressed from many points of view. I have also suggested that the hegemony of the alienation-story over the understanding of humanism ignored the external forces that constitute subjectivity and forms of intersubjectivity. As a consequence, it over-simplified the revolutionary possibility of identifying the limit of a social formation from within it, losing the sense in which the Freudian unconscious of an individual or a historical world can never be made transparent within it such that the Marxian relationship of analysis and action became much more problematic. Finally, I have suggested that the existentialist collapsing of the distinction between the transcendental constitution of the possibility of meaning and the concrete subjectivity who enacts meaning placed too high an emphasis on what can be accomplished by individual decision or choice and, moreover, occluded the significance of death and tragedy for individual subjectivities. How might the general outline of a philosophy for our time emerge from pushing these critiques further?

It would require a philosophy of technology that considers the role of technology on both the built environment and the natural ecology. It would require a recovery of the universality of humanity as against the contemporary fragmentation of differences into an identity politics that sees no commonality in the “human” and thus cannot think together the different forms of oppression and exploitation. It would require an acceptance of death, limitation and tragedy as the fate of individual subjectivities. It would require a re-justification of the transcendental dimension of human experience as against the contemporary tendency to limit individuals within their immanent experience.[48]

[1] Benedetto Croce, What is Living and What is Dead of the Philosophy of Hegel, trans. Douglas Ainslie (London: MacMillan, 1915 ) p. 214, 206.

[2] This paper was first given as an oral address to the conference Then and Now: 1968-2018, November 2-3, 2018, Institute for the Humanities, Simon Fraser University, Vancouver.

[3] Investigating philosophy as a discursive space within a cultural history requires a different methodology than one would use for investigating a specific philosopher or philosophical theme. The choice of authors and references is determined by their popularity and significance at the time more than their intrinsic content or continued validity.

[4] The first translation into English was actually in 1959 by Martin Milligan for Foreign Languages Publishing House (which later became Progress Publishers) in Moscow. Perhaps because this edition came from the official Soviet Communist publishing house, or perhaps because of Fromm’s humanist introduction to his slightly later edition, it is Fromm’s text that became significant for the philosophy of the Sixties. a translation which presumably came from an earlier collection that he co-edited. Bottomore had earlier published T.B. Bottomore and Maximilien Rubel (eds.), Marx: Selected Writings in Sociology & Social Philosophy (London: Watts, 1956; Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1963) which contained short excerpts from the 1844 Manuscripts and was presumably the basis for Fromm’s invitation.

[5] Erich Fromm, Foreword to Karl Marx: Early Writings, trans. and ed. T.B. Bottomore (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1963), iii.

[6] Erich Fromm, Marx’s Concept of Man, with a translation from Marx’s Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts by T.B. Bottomore (New York: Frederick Ungar, 1971), 42. Nevertheless, the 1844 Manuscripts relied on the theory of material pauperisation to explain the increasing misery of the working class that would turn it into a revolutionary agent. Since work is a loss and servitude of the worker, Marx concluded that “the greater his activity, therefore, the less he possesses.” This part of the Manuscripts was an insoluble problem for an analysis of alienation centred on consumerism, such that it often was interpreted in a purely spiritual-moral sense—which was also intended by Marx alongside the material dimension. See Karl Marx, “Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts: First Manuscript, Alienated Labour,” Karl Marx: Early Writings, trans. and ed. T.B. Bottomore (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1963), 122.

[7] Fromm, Marx’s Concept of Man, 57, 71ff.

[8] Erich Fromm (ed.), Socialist Humanism (Garden City: Doubleday, 1965), x. Even Herbert Marcuse’s characteristic critical tendency was limited in his contribution to this collection to a critique of the purported rejection of violence in the term “humanism,” for which he relied primarily on the work of Maurice Merleau-Ponty.

[9] Louis Althusser, “The ‘1844 Manuscripts’ of Karl Marx” in For Marx, trans. Ben Brewster (New York: Vintage, 1970). Originally published in La Pensée, December 1962.

[10] Erich Fromm, Beyond the Chains of Illusion: My encounter with Marx and Freud (New York: Continuum, 1962), 86, see 16-8, 40-4, 85-7, 132.

[11] Gajo Petrović, Marx in the Mid-Twentieth Century (Doubleday: Garden City, 1967), 80.

[12] Ivan Svitak, Man and His World: A Marxian View, trans. J. Veltrusky (New York: Dell Publishing, 1970), 153.

[13] Mihailo Marković, From Affluence to Praxis (Ann Arbour: University of Michigan Press, 1974) p. 234.

[14] Marković, From Affluence, 191.

[15] Fromm, Marx’s Concept of Man, 70-1.

[16] Karel Kosík, Dialectics of the Concrete, translated by Karel Kovanda and James Schmidt (Dordrecht: D. Reidel, 1976, originally published in Czech in 1963) p. 48.

[17] Kosík, Dialectics of the Concrete, 106.

[18] Jean-Paul Sartre, The Transcendence of the Ego, trans. F. Williams and R. Fitzpatrick (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux: 1957), 98-101.

[19] Sartre, The Transcendence of the Ego, 105.

[20] Walter Kaufmann, Existentialism From Dostoevsky to Sartre (New York: New American Library, 1956), 292-3. This was the commonly available edition which included Sartre’s essay during the 1960s.

[21] Herbert Marcuse, “Existentialism: Remarks on Jean-Paul Sartre’s L’Être et le Néant,” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, Vol. 8, No. 3, March 1948.

[22] Herbert Marcuse, “Sartre’s Existentialism” in Studies in Critical Philosophy, trans. Joris de Bres (London: New Left Books, 1972), 190.

[23] Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed: 30th Anniversary Edition, trans. Myra Bergman Ramos (New York: Continuum, 2000), 76 ftn. 2, 81-2.

[24] Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex, trans. H.M. Parshley (New York: Bantam, 1953), 30; Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, trans. Constance Farrington (New York: Grove Weidenfeld, 1968), 10.

[25] Kwame Nkrumah, Consciencism: Philosophy and Ideology for De-Colonization (Modern Reader Paperback: U.S.A., 1970), 70, 106.

[26] Herbert Marcuse, One-Dimensional Man (Boston: Beacon, 1968), xv.

[27] Kwame Nkrumah, Neo-Colonialism, the Last Stage of Imperialism (London: Thomas Nelson, 1965), 255.

[28] Michel Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archeology of the Human Sciences (London: Tavistock, 1970) p. 349.

[29] Ibid, p. 422.

[30] Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, Volume I: An Introduction (New York: Random House, 1978), 8.

[31] Foucault, The History of Sexuality, 126, ftn.

[32] Foucault, The History of Sexuality, 12.

[33] Fromm, Beyond the Chains of Illusion, 86.

[34] Jacques Derrida, “Structure, Sign and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences” in Richard Macksey and Eugenio Donato (eds.), The Structuralist Controversy: The Languages of Criticism and the Sciences of Man (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1970) p. 249.

[35] Ibid, p. 265.

[36] Jacques Derrida, “The Ends of Man,” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, Vol. 30, No. 1, Sept. 1969, p. 34. This was the first publication of the lecture in English and was accompanied by commentaries by Richard M. Zaner and Richard Popkin. The essay was later collected in Jacques Derrida, Margins of Philosophy, trans. Alan Bass (Brighton: The Harvester Press, 1982) and was no doubt known more widely as a result.

[37] Ibid., p. 39.

[38] Ibid., p. 56.

[39] Marilyn Nissim-Sabat has recently contested the current postcolonial reading of Fanon that foists upon him an outright rejection of humanism as opposed to a decolonial reading that recognises the humanist ethical spirit of Fanon alongside the deformations of that spirit by colonialism. See Marilyn Nissim-Sabat, “Decolonial Humanism: Reflections on Fanon, Marx, and the New Man” on the blogsite Brotherwise Dispatch Vol. 3, Issue 5, Dec. 2018-Feb. 2019. Available at https://brotherwisedispatch.blogspot.com/2018/12/decolonial-humanism-reflections-on.html.

[40] This dominant figure was not deployed by all Marxist humanists, however, especially not those who attempted to establish a continuity between an earlier Marxism and the New Left. For example, see Raya Dunayevskaya, “Marx’s Humanism Today,” in Erich Fromm (ed.), Socialist Humanism, 68-70.

[41] As soon as one appreciates the analyses of technology and surplus productivity from Capital, Vol. 1, it is clear that the work Jacques Derrida, ing class can be exploited to a greater degree and yet simultaneously gain a higher standard of living. As a consequence, Marx’s claim for the crucial role of the working class within capitalism as a revolutionary force becomes complicated, to say the least, and probably unsustainable.

[42] Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Vol. 1, trans. B. Fowkes (New York: Vintage, 1978), 286-7.

[43] Karl Marx, Capital, Vol. 3, ed. Frederick Engels (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1972), 632.

[44] Edmund Husserl, The Crisis of the European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology, trans. David Carr (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1970), 184.

[45] Edmund Husserl, Analyses Concerning Active and Passive Synthesis: Lectures on Transcendental Logic, Collected Works, Vol. LX, trans. A.J. Steinbock (Dordrecht: Kluwer, 2001) Appendix 8, Part 10, 466-471.

[46] Herbert Marcuse, “The Concept of Essence,” in Negations, (tr.) J. J. Shapiro (Boston: Beacon, 1968), 87; Herbert Marcuse, Reason and Revolution: Hegel and the Rise of Social Theory (Boston: Beacon, 1969), 251–57; Herbert Marcuse, “On Science and Phenomenology,” Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science, Vol. 2: In Honor of Philipp Frank (Proceedings of the Boston Colloquium for the Philosophy of Science, 1962-4), (ed.) R. S. Cohen and M. W. Wartofsky (New York: Humanities Press, 1965), 280.

[47] Karl Marx, Karl Marx: Early Writings, p. 157-8.

[48] These are the challenges that my recent book Groundwork of Phenomenological Marxism: Crisis, Body, World (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2021) attempts to address.