Christopher Hitchens’ Hitch-22 and Arguably: Essays

Christopher Hitchens publicly courted posterity’s verdict and repeatedly stated the standard by which he sought to be judged. Introducing Arguably, the essay collection that appeared a few months before his death in December 2011, he notes that in a 1988 book, Prepared for the Worst, he’d “annexed a thought of Nadine Gordimer’s, to the effect that a serious person should try to write posthumously.” In A Long Short War: The Postponed Liberation of Iraq (2003), he reiterates this intention to write without regard for readers’ reactions, for current fashion or for prevailing opinion (but doesn’t mention the novelist Gordimer). Encapsulating his core conviction, he concludes Why Orwell Matters (2002) by asserting that “it matters not what you think, but how you think.” He says this again in God Is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything (2007) and multiple times in his memoir Hitch-22 (2010). Hardly a relativist, Hitchens meant that beliefs arrived at by way of independent, informed, cosmopolitan, ironic, critical thought have better hope of holding up over time than ideas accepted on faith, parochial or literal-minded in nature, or tailored to follow a party line. Assessing Hitchens on these terms, it’s fair to say he couldn’t consistently meet his own ideal even if he did produce many essays of enduring value. For it was as an essayist, more so than as a polemicist, that he excelled.

Despite his pleas, many readers and cable television talk show watchers probably cared more about what Hitchens had to say than how he said it – the positions he took rather than his intellectual method. Though commonly seen as having taking a turn to the right, from the socialism of his youth to the bellicosity of his last decade – from being a Nation magazine columnist for twenty years to being someone who gleefully attacked the likes of Noam Chomsky and Michael Moore – Hitchens invoked the legacy of the left to explain his support for military intervention in Iraq, even if he couldn’t resist simultaneously throwing a jab at contemporary anti-war protesters. “Not all leftist three- or four-word slogans have always been absurd,” he writes in the introduction to A Long Short War. “‘No War on Iraq’ in 2003 may conceal the silly or sinister idea that we have no quarrel with Saddam Hussein, but the 1930s cry – ‘Fascism Means War’ – is worth recalling. It preserves the essential idea that totalitarian regimes are innately and inherently aggressive and unstable, and that if there is to be a fight with them, which there must needs be, then it is ill-advised to let them choose the time or place of engagement.” George W. Bush and Tony Blair were absolutely right, then, and right on principle, to overthrow the Iraqi dictator before things got truly out of hand. Some attentive readers might wonder whether the implied assumptions that Bush and Blair were well-advised in their planning of the engagement, suitably equipped to foster the stability so sorely absent in the region, and accurately informed about the specific rather than general reasons for entering into armed conflict might indicate a failure of skepticism on Hitchens’s part and an unusual confidence in the wisdom of political leaders.

Hitchens believed being right was the main thing, even if things went wrong. “Surely, identifying the situation that is appropriate for intervention is both an art and a science,” he allows in a 2008 piece (not explicitly about Iraq) included in Arguably. Yet “taking a stand on principle” remains worth doing “even if not immediately rewarded with pragmatic results.” In his view, “war and conflicts are absolutely needful engines for progress and … arguments about human rights, humanitarian intervention, and the evolution of international laws and standards are all … part of a clash over what constitutes civilization, if not invariably a clash between civilizations.” Of course, debating what constitutes civilization, and identifying its true cultivators and its insidious opponents, offered more intellectual stimulation than worrying over whether Saddam Hussein actually had monstrous weapons of mass destruction stockpiles, actively sought them, or merely dreamed of possessing them.

Even when Hitchens concedes possible errors or acknowledges changes in his stances, he suggests he was never really wrong at all and that others, not him, strayed from fundamental principles. Though he ceased identifying himself as “a man of the Left,” he insists in Hitch-22 that it was those who opposed the overthrow of Saddam Hussein who betrayed the left’s proud history of anti-fascism. He didn’t abandon former comrades; they crept wretchedly from him. Though he says he “probably” came to “know more about the impeachable incompetence of the Bush administration than do many of those who would have left Iraq in the hands of Saddam,” he wouldn’t retroactively retract his support for war. “If I could have had it proved to me beyond doubt that he did NOT have any serious stockpiles on hand, I would have argued – did in fact argue – that this made it the perfect time to hit him ruthlessly and conclusively.” If he was ever wrong, he had impeccable reasons – and someone else was much more wrong anyway. That is how he thought.

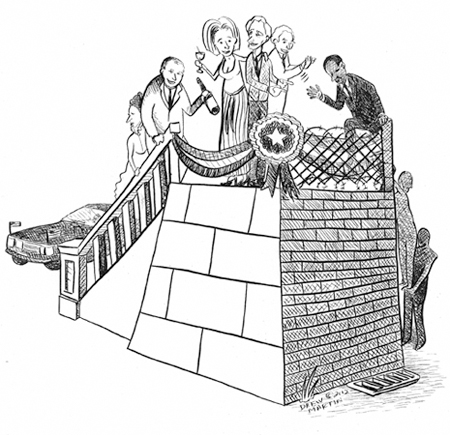

Eluding easy classification, which Hitchens seems to see as a sign of individual cleverness, provides him with the conceit around which he organizes his memoir. He doesn’t narrate the education of a contrarian (a label his disliked); rather, he strings together anecdotes (almost like a series of essays) shaped to show how living a kind of double life provided him with acute powers of observation. Sometimes the taking on of a new identity is a formal matter, as when Hitchens, born British, becomes an American citizen. It can have metaphorical aspects, as when he wants both to participate in events and cover them in “the Janus-faced mode of life” of a politically active journalist. He set out to be both “an ally of the working class,” he claims in Hitch-22, and something of an aesthete who enjoyed the connections with establishment figures his years at Oxford offered him. Thus, his memoir’s title names a condition involving the struggle against both absolutists and relativists, the simultaneous “admission of uncertainty” (which he advocates more than he performs) and “repudiation of the totalitarian principle,” and the habit of attending both protest marches and posh soirees).

Although he doesn’t present Hitch-22 as a full-fledged autobiography, the memoir is oddly unrevealing. (The Vanity Fair essays on his esophageal cancer diagnosis and treatment Hitchens wrote during his last year are far more intimate and present unblinking reflection on his individual experience, or a momentous part of it: the end.) As I hint at above and discuss more below, much of what he shows of himself he’d already exposed in print. He comes across as less interested in introspection than in arguments. He does begin Hitch-22 with remembrances of his parents (an especially affectionate one in the case of his mother, who committed suicide), but he only mentions his wife and children in passing. If he offers evidence from his personal experience, he does so mainly to illustrate points in the ongoing debates that fueled a sizeable portion of his work. Describing his friendships with other writers allows him to revisit peak moments in the life of his disputatious mind. Though his account of a firm bond with novelist Martin Amis mostly amounts to a vigorous celebration of friendship, it also summarizes a disagreement the pair had over the history of communism. Recollections of his relationship with Palestinian-American intellectual and literature professor Edward Said lead Hitchens to ventilate his annoyance with the belief “that if the United States was doing something, then that thing could not by definition be a moral or ethical action.” Hitchens finds this all too common with former friends and associates. (Hitchens had no compunction about disparaging the dead and presumably didn’t expect scrupulously polite obituaries.)

Said factors in Hitchens’s story, and in other writers’ intersecting stories, in another noteworthy way – one that suggests that a small literary community in which everyone knows (but doesn’t necessary like) everyone else actually does exist. As happens in such an environment, a squabble or minor conflict can take on outsize proportions. Such people care passionately about their interpretations of events – and they commit them to print. A volume of Saul Bellow’s letters appeared soon after Hitch-22 did. Corresponding with author Cynthia Ozick, Bellow describes a recent, disagreeable dinner with his younger friend Amis and Hitchens (the latter someone of whom he’d not previously heard). Amis writes of the same contentious meeting in his autobiography Experience (2000). Hitchens (who correctly calls Amis’s account “slightly oblique and esoteric”) offers his version of the evening in Hitch-22 (having already rehearsed it in a 2007 Atlantic piece reprinted in Arguably). Though all three agree that Said and Hitchens’s understanding of the duties of friendship factored in the dispute that erupted before dessert, they differ in emphases and on recollections of facts. Amis wanted to avoid a scene for Bellow’s sake; Bellow wanted to avoid a scene for Amis’s sake. Hitchens did not mind causing a scene. Bellow concludes that that’s all that mattered to Hitchens and other “Nation-type gnomes,” whereas Amis credits Hitchens with more depth than that (as does Hitchens, of course). Amis believed his two friends fought about Israel, though Said did come up. For Hitchens, Said was the focus, and he believes Bellow intended all along to steer the conversation to a controversy over Said’s origins and views of terrorism. (In their respective versions of the event, different journals are claimed to have started the row: Hitchens remembers a carefully placed, marked-up Commentary article about Said; Bellow mentions a Critical Inquiry essay by the author of Orientalism that he just happened to have at hand.) Both Amis and Hitchens greatly admired Bellow’s fiction, and Hitchens knew Amis intended a high gift in introducing him to the novelist, but politics ruined what could have been a fine evening.

Such maddening interference in literary life is something of an ongoing theme in Hitchens’s story. At a reading from The Trial of Henry Kissinger (2001), I saw Hitchens hold up a copy of another volume of his, Unacknowledged Legislation: Writers in the Public Sphere (2000), and heard him say he wanted to be remembered for such literary essays rather than books like his brief arguing for charging the former Secretary of State for war crimes, but that he couldn’t ignore, or stop writing about, political developments. Like Michael Corleone into the mob in the worst of the three Godfather movies, Hitchens couldn’t help being pulled into history. The Ayatollah Khomeini’s fatwa calling for the death of his friend Salman Rushdie for having written The Satanic Verses – which Hitchens writes about in For the Sake of Argument (1993) as well as Unacknowledged Legislation, Letters to a Young Contrarian (2001), God Is Not Great, Hitch-22 and numerous magazine articles – illustrates how and why. The affair of the fatwa, by plainly demonstrating the threat religious fanaticism poses to unfettered thought and to civilization itself, spurs Hitchens the memoirist to state his principles by listing what he hates (“dictatorship, religion, stupidity, demagogy, censorship, bullying, and intimidation”) and what he loves (“literature, irony, humor, the individual, and the defense of free expression”). Literary essays dominate the “Love” section of the 2004 collection Love, Poverty, and War – though his other concerns get equal or greater space. Such enthusiasm might explain why so few of his Slate columns, which he used mainly to comment on news of the day, ended up in Arguably, which instead consists largely of book reviews, some of which he knew were among his “very last.” (I once gave the title “Hitchens in Love” to a review of God Is Not Great, and while I claim no special insight, since he penned many attestations to his adoration of literature, I can’t help noticing how routinely this aspect of his work gets overlooked, or relegated to commentators’ respectful notice of his wide range of references to novelists and poets.)

Though Hitchens fully earned his reputation for animadversions, in his essays on literature he shows qualities often absent from his political pieces, such as generosity, graciousness, forbearance, humaneness. His tone changed when he aimed to encourage appreciation rather than win an argument. He had the capacity to enjoy the work of writers, like Evelyn Waugh, whose political and religious beliefs he despised. Echoing and amplifying George Orwell’s “great and noble defense of Wodehouse against the wartime calumny that was spread about him,” Hitchens finds it impossible that the creator of Jeeves, Psmith and Sir Roderick Spode knowingly collaborated with the Nazis, even if P.G. Wodehouse did appear on Nazi radio after the fall of France. Hitchens relies on his historical knowledge to defend the comic novelist’s innocence. Wodehouse once joked, of the Polish region where he was interned after being deported from France, that “there is a flat dullness about the countryside which has led many a visitor to say, ‘If this is Upper Silesia, what must Lower Silesia be like?’” This might appear callous, at best, given that Auschwitz was in Silesia, but, as Hitchens points out, Wodehouse couldn’t have known about what was going on there, and that the Nazi’s didn’t implement their Final Solution until after Wodehouse was gone. It’s hard to imagine Hitchens trying to shield a candidate for office, for example, from such unseemly associations. Indeed, he excoriates serial presidential candidate Pat Buchanan for his views about World War II (i.e., that it was not worth fighting). But fine wordsmiths could soften his heart.

Although long after their first meeting in 1989 Hitchens and Bellow continued to differ on Palestinian-Israeli issues generally and Edward Said specifically (even if his inclination to stand up for the latter weakened), Hitchens retained intense admiration for Bellow’s fiction. In the aforementioned Atlantic essay in Arguably, he singles out The Adventures of Augie March for praise, declaring one particular line –“What use was war without also love?” – to be “one of the most affirmative and masculine sentences ever set down.” (The remark draws attention to the fact that the majority of writers Hitchens celebrated were men, even if Nadine Gordimer did supply him with his writerly code. Other statements, like the following, suggest that Hitchens may have come to see something of himself in Bellow: “His life as a public intellectual is sometimes held to have followed a familiar arc or trajectory: that from quasi-Trotskyist to full-blown ‘neocon’…. But Bellow’s political evolution was by no means an uncomplicated or predictable one.”) He sounds a similar note in an essay on Philip Larkin. Though the occasion of the piece was the publication of Letters to Monica, letters chronicling “perhaps the least romantic story ever told” (that of the poet’s “distraught and barren” relationship with his long-suffering long-term partner Monica Jones), Hitchens manages to conclude it with some of the bard of suffering’s most positive lines: “Our almost-instinct almost true: / What will survive of us is love.”

Even if, like his writer hero Orwell, Hitchens never really regarded literature and politics as discrete categories, he might get his wish and end up more closely identified with the former –at least for as long as those whose writing about literature rises to the level of literature are remembered.

John G. Rodwan, Jr., author of the essay collection Fighters & Writers, lives in Detroit.