Robert Cohen’s Freedom’s Orator and Edward P. Morgan’s What Really Happened to the 1960s

Robert Cohen,“Freedom’s Orator”: Mario Savio and the Radical Legacy of the 1960s (Oxford, 2009)

Edward P. Morgan, What Really Happened to the 1960s: How Mass Media Culture Failed American Democracy (University Press of Kansas, 2010)

On 15 November 2011, at the same spot on the Berkeley campus where “freedom’s orator” emerged into history in 1964, thousands gathered to commemorate Mario Savio and to protest against the police assault on OccupyCal a few days before. At the request of the Occupiers, the Mario Savio Award committee agreed to hold their 2011 award ceremony on the Steps officially dedicated to him. So on that chilly November evening we gathered to remember the past and to act in the present. And when Lynne Hollander Savio, Mario Savio’s widow, asked for those who had participated in the Civil Rights Movement, then the Free Speech Movement, then the Anti-War Movement, and so on down to Occupy, to raise their hands, an elderly woman in my vicinity, confined to a wheelchair, had her fist in the air from first to last, as did hundreds upon hundreds of others. Berkeley’s past and present came together that evening in a trans-generational moment of a sort all too rare in the neo-liberal era: a moment of political opposition rooted in a deep sense of connectedness, of understanding of each other’s hopes and fears, combined with a determination to act. It was, I think, an extraordinarily educative moment for all concerned–for far too long, many of us from the past have tended to bewail the apolitical younger generation, while many of the younger generation have found our preoccupation with our past irrelevant. It was a moment uniquely generated by the Free Speech Movement and Occupy together. Yet it was not a uniquely Berkeley moment, although that it occurred in Sproul Plaza did lend it a particular aura. For Occupy Wall Street–like its precursor, the Wisconsin rising–has been notable for again bringing young and old onto the streets of America.

Since Occupy has so altered the climate of political judgment, there is now no need to treat the books by Cohen and Morgan, published before 2011, as if their value resides solely in whether or not they rescue their historical subjects from condescension and misrepresentation. Published amidst so much despair that any movement against the dominating rottenness of our times would ever materialize, their authors surely also aimed to do what they could to weaken that domination. But there have been many other efforts to confront the worldview insinuated by the mass media, as Morgan argues, into all the nooks and crannies of our understanding. So while it may be debated how much and in what ways any of these has contributed to the present rejection of and assault upon a system and its supporting ideology whose existence is suddenly so widely perceived to be incompatible with society, the contribution of these two books should not be exaggerated and should not be the basis on which they are judged. They are, nevertheless, worth considering for the encouragement and warnings they provide as we again confront our actually existing democracy.

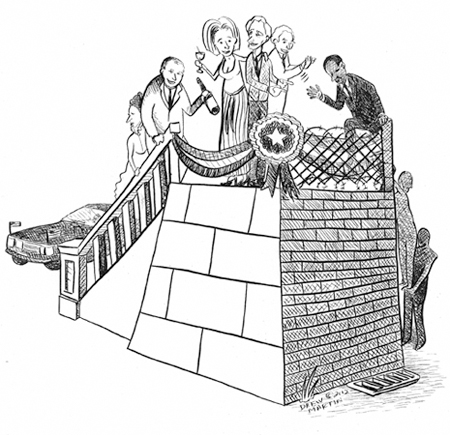

A first warning: The uplifting feeling, palpable at the Savio Steps, that we all–or at least 99% of us–are involved in something necessary and life enhancing, deserves scrutiny. For as Morgan warns, we have all been subjected to mass media relentlessly bent upon bending us to conservative notions of what is and is not permissible by (re)writing for their own ends our history even as we live it. And we all to some degree inhabit these system-serving misconstructions. (That the social conflicts of the Sixties were merely generational conflicts, is one of the distortions he emphasizes. That it was all merely the folly of youth is, as we will see, one of the accusations directed against Savio towards the end of his life by one of his last political opponents.) So the feeling that we are now engaged together in something vital is not enough. Bridges of understanding anchored in re-examined and re-invigorated self-understanding need to be fashioned. Both these books can help us rid ourselves of the prevailing “odious” order of things we have in part internalized and encourage us, now that the first rush of joy in action is past, begin the necessary long, slow boring of the hard board.

No matter that an emphasis on generations is problematical, Cohen’s detailed account of the Free Speech Movement will almost certainly remind some of us that we once were so, so young. Still, it comes as a bit of a shock to be told in the book’s opening words that Savio was only 21 when he burst upon the political scene. Of course, many in the Free Speech Movement –or in the Civil Rights Movement, in which Savio was active (and educated), in Mississippi, in the Freedom Summer of 1964–were young. But then, as now in Occupy, youth proved no barrier to political invention and sophistication. The politically unsophisticated, the leaden footed who never seemed to be able to take a right step, were those then, as now, already ensconced in positions of power and privilege. But Cohen’s account of Savio’s political engagements after 1964 shows that the self-perpetuating oligarchy’s early setbacks proved in many respects temporary. How this hydra grew new heads, is Morgan’s subject. How to go on wrong-footing today’s oligarchs and how to prevent them from growing two new heads when one is cut off, is a key problem facing Occupy today. If that is to be done, it will require ever more political imagination and inventiveness. It will also require awareness of the sort that Morgan provides concerning how the vast apparatus devoted to defining and manipulating thought and action operates.

Cohen also warns that those seeking to undo the system must avoid wrong-footing themselves. His account of the failure of the effort at Berkeley in Spring 1965 to defend the freedom to speak even obscenely shows that it is certainly possible for someone, even someone widely respected as a leader, to try to lead where few will follow. As it became clear that the FSM leadership was divided on the issue and that only hundreds rather than thousands were willing to defend “filthy speech” with their bodies, Savio backed away from it. But some damage had already been done. Now, as then, there are a great many matters that agitate some of us more than others. But not all of them are of the same political significance. One must hope that Occupy manages collectively to winnow the wheat from the chaff and avoids wasting time and energy on things that are politically marginal and marginalizing. Yet, again, however, as Morgan warns, Occupy’s efforts to make Occupy grow are being frustrated by the fact that at every turn we are subjected to a process that treats us as an audience rather than actors, that plays on our emotions in such a fashion as to “[draw us] into a culture of consumption and entertainment that provides . . . a compensatory but ultimately erosive sense of empowerment”–something that certain sorts of issues and actions seem to lend themselves to.

While Cohen’s biography takes note of the resurgence of the system under the leadership of far right-wingers, it does not dwell on how that came about. It does, however, show how, after FSM, Savio engaged with this unwelcome reality –which brings me to the most poignant aspect of this book. Poignant not because Savio’s time in the political sun was so short (although his was a life of political engagement until its end), nor because he died too soon. The poignancy springs from being reminded so forcefully that those are vulnerable human beings who choose, because where and who and what they are leaves them no other choice, to “put [their] bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon the whole apparatus” to try to stop “the operation of the machine [which has become] so odious, [which] makes [one] so sick at heart, that [one] can’t take part.” Yet these same circumstances helped Savio, who long suffered a speech defect, to find his voice, just as today’s circumstances are helping some to find a voice they did not know they had. Cohen thus reminds us that those we now see facing the militarized police are not superheroes; they’re not going to spring up after the state juggernaut has rolled over them to continue the struggle unscathed. Those crushed by power seeking to persuade that it should still be worshipped are surely courageous. But they are being hurt, and so long as the struggle goes on they will continue to be hurt, in their minds as well as in their bodies. That Savio was vulnerable and that, aware of his own vulnerability, he nevertheless went on to act, is a mark of his courage. That Savio was vulnerable and that those close to him in 1964 and thereafter knew he was vulnerable, explains, I think, why those who knew him loved him warmly and supportively, but with no hint of idolatry.

Savio was certainly not alone in his vulnerability. We who went through those dreadful yet inspiring years surely all know someone whose life was knocked off course. We even know some who, unlike Savio who rediscovered his early scientific interests, failed to find a new satisfying course for themselves. The same will surely happen this time around. So, many of the young who are risking so much of themselves will need encouragement as they deal with the consequences of their actions. This is another warning. But Cohen’s book encourages one to hope that support will not be lacking. As the recent gathering at the Mario Savio Steps also bore witness, it was a genuine community that came into being at Berkeley in 1964. And evidently many of those who joined it have found it a lifelong source of friendship and support, and an instrument through which to critically perceive and engage with society and its media.

Butt all was not sweetness and light within the FSM. Cohen makes it clear that circumstances, personalities and politics led to internal conflicts. And no one, certainly not Savio, emerges as a saint–although Cohen’s account of Savio’s background, especially the importance to him of the teachings of the religion from which he had lapsed, might mislead some to thinking so. The all-inclusiveness of the movement, beginning with the initial mass 32-hour encirclement of the police car into which the first arrestee, civil rights activist Jack Weinberg, had been dragged, meant that it encompassed many political persuasions, including even some conservatives. That made conflict inevitable. Some differences could be reconciled; others could not. Many of these, which surfaced, as Cohen makes clear, at that founding moment of “The Sixties,” are still with us. None has perhaps been more disruptive than that which separates those who insist it is necessary to make deals with those who possess power from those who insist that the latter must be relentlessly subjected to pressure and that their limits, which are the limits of the system itself, must be exposed by confronting them/it with demands for non-reformist reforms they/it cannot concede without simultaneously surrendering part of their/its basic nature. Savio was ever ready to argue against conceding too much too quickly to faculty and administrators, who could not be trusted, especially where the principle of freedom of speech on campus was concerned. He also used his remarkable ability to persuade enormous crowds of people, many of whom accorded him a special trust, to support the approaches he favored. And no doubt this too antagonized those on the FSM’s Steering and Executive committees who disagreed with him.

Of course, he antagonized others outside the Movement even more. And as Cohen notes, those antagonisms endured. They certainly surfaced 30 years later when Savio joined in opposing a fee increase at Sonoma State University, where he was an untenured lecturer in physics. There an administrator compared encountering Savio’s very public political activism against the corporatization of higher education to “watching . . . a reformed alcoholic saying, ‘You know, life was more fun when I was a drunk. And I’m going to start indulging again.” For that administrator, Savio’s radicalism was only a childish indiscretion he should have outgrown. That he had not done so showed he was addicted to it. What such critics do not get is that there can be transformative experiences in people’s lives which forever preclude surrender to the odious machine no matter how it may have been restyled. No doubt some of the young engaged in Occupy, including those who have joined in today’s struggles against tuition fees and other aspects of the still advancing corporatization of the public education system, will similarly find that they have been transformed and that their lives have been forever marked, for good and ill, by this deeply personal political act.

That others long harbored antagonisms, and that they similarly failed to recognize that the FSM–or, more generally, the movements of the Sixties– were, for many, deeply transformative, is further evident in some of the ways in which, as Cohen describes, Savio was remembered after his death. Not just the Mr. Joneses of the world, but even world-famous philosophers seem to be as incapable now, as they were then, of knowing what is happening. So again a warning: Don’t expect those who experience Occupations as the rejection of their values and way of life to acknowledge that these are principled actions. To them, these principles will remain incomprehensibly wrong, for they require leaps of sympathy and of the imagination beyond their capacities. Expect their endless rancor.

But why are some people locked into the belief that, bad as it may be, this is still the best of all possible worlds? Why cannot some people see that a new world is necessary? Of course, not everyone sees everything in the same light and it is surely legitimate not to do so. And when talking of how we live and how we ought to live, heated words are unavoidable. But beyond that, at least some of the war of words surely erupts because ‘we’ feel that ‘they’ do not listen to us, do not take ‘us’ seriously. Again, this is to be expected. For we all have many things on our minds and none of us can engage to do something about every terribly pressing matter. There is, however, a further problem with the way we live, a problem that, according to Morgan, is lodged in the way we learn about our world and its problems.

That those who know the Sixties only through the ways it has been presented in our culture think of it in ways often unrecognizable to those of us who lived through it, should not surprise us. But even we who live with “our own memories” of the Sixties live with the distortion of these memories. For we, too, have been subjected, as Morgan argues, to mass media “grounded in the broader political economy [which] shape media outcomes systemically,” which “provides the public with an endless stream of imagery, distorted claims and personalities they can loathe, embrace, or emulate–and not much else.” Perhaps when it comes to matters with which we were intimately engaged, we retain some sense of what really happened. Concerning matters which engaged us peripherally, our memories are less to be trusted–not just because our memories become more fallible with the passage of time, but more because a number has been done on us too. And so we, too, live, however uncomfortably and resistantly, in that world of “ideological and identity enclaves” framed by the “highly imagistic media culture[‘s]” exploitation of “the Sixties.” We, too, especially when we seek to converse with those who do not agree with us, find ourselves discoursing according to the parameters laid down in that media culture which reduces “the likelihood of democratic conversation among the citizenry” while sharpening our differences as we each bring to the conversation a half century, almost, of unrelieved emotion. And so we too often dance the same old dance to their tune.

This is why the Occupy movement has been so refreshingly different. It opened the door to the discussion of things that had long been off the table in ways that the media-supported dominant ideology had long ruled illegitimate. Opposition to the neo-liberal system began to find a new voice. Occupy held out the promise that it would break free of that decades long debilitating pseudo-discussion of constricted possibilities and make something like a democratic conversation possible. But in some places, the weight of that illusory “past” has proved too much, pressing people back into trying to engage in fruitless ways with misleadingly defined issues. The warning is clear. If we are to avoid dancing the same old dance, the Sixties must be engaged with critically. The ideas and practices that informed that inspiring historic era must not be trundled out again half a century later by would-be emulators locked into an erroneous, media-constructed understanding of that era. Morgan’s suggestion, that “we need a reckoning with this past that we can learn from, not a discourse that keeps a distorted past alive while simultaneously trying to bury it,” is surely correct.

And so back, finally, to Mario Savio and the FSM. For what Cohen’s account clearly shows is that the FSM was also notable above all for speaking in ways that made political conversation fresh and meaningful, something that correlated with Savio’s own non-sectarian leftism. Yet while Savio himself seems to have remained free from ideological cant, the larger politics of opposition all too quickly diminished to conflicts among unyielding orthodoxies. That, perhaps, is the final warning to be taken from these books: that meaningful political conversation is terribly hard to maintain when so much surrounding us and in ourselves encourages us to keep on gnawing away at the same old stale cake of custom.

_________

Robin Melville used to teach politics at a liberal arts college in Wisconsin.