The Clogged Capillaries of the Peruvian Amazon

When one decides to take the trip into the jungle city of Iquitos – the largest city in the world inaccessible by road – there are two options. The first is a flight by one of Peru’s many domestic airlines, 5 to 10 times per day, with a flight time of approximately 2 hours. This will cost between $100-$200 one way, far too out of the range of the average Peruvian worker who in Lima can make 50 soles per day ($18.50 on today’s markets), and in the provinces a mere 25-30. And certainly out of the range of my budget, a traveling journalist on a mission to send home my stories of peeling through the carefully crafted and commodified layers of culture that are for sale on the international market for anyone who is willing to pay the steep fees for “experiences”.

The need to travel to and from the Amazon on a budget has given rise to the network of river ships that carry cargo, livestock, and people to and from Tarapoto, Iquitos, and Pucalpa – to name a few Peruvian ports – and sustain the human presence deep within the jungle. As I arrived to the port of Yurimaguas that night after having been delayed a few hours due to land slides that often plague the roads swerving between mountains in the high jungle, I was presented with a pleasant and comforting illusion as most things present themselves when you are a foreigner traveling through the jungle. There was an empty ship, its pale blue steel stood as a reminder to all of how the sky and heavens reflect to the iris before being shrouded in a thick pillow of clouds that replenish the Amazon with its life source of sudden and heavy sheets of rain. The three floors were stacked like a jenga puzzle, with neither windows nor walls, allowing the few gusts of wind that find themselves in this area of the world to break the stranglehold and provide relief to all those suffering from the stifling humidity. The green, murky waters of the Amazon slapped up against the side of the ship as it shuddered up and down with the current; a whole new world of mysterious and magical creatures living below the river’s dirty shell adorned with drifting pieces of wood and plastic soda bottles.

The ride lasts for 3 days, but nothing is ever on schedule. The ships leave as they fill, and after learning that most of the cargo trucks were jammed in the same landslide that had affected me, I quickly began to understand the reason the ship was empty for the first night. In order to travel on the Amazon a hammock was required, unless one preferred to spend the nights on the steel floor, as well as some kind of plate or bowl to receive the scoops of rice and boiled plantains that were provided with passage. As the ship crammed with passengers the following morning and hammocks were tied up encircling me on all sides, my unexpected quest to learn about the Amazon region through the eyes of my compatriots began. Most adults only said a few words to me during mealtimes, still trying to get used to the fact that I was obviously not from Peru yet was using the local mode of transport. The children would always be running by asking me questions, having me point out where I came from on maps that were usually only of Peru, dumbfounded when I tried to explain to them my country was far above the limits of the paper they held in front of me. In turn they told me about their lives, their favorite foods, their hopes and thoughts.

As the ship left port every passenger crowded along the edges, hanging onto the steel poles that wrapped the ship, waving goodbye to relatives, staring out onto the port, or examining the herd of cattle that was encased behind wooden railings quickly latched together at the last minute before departure. The first observation that took my breath away was only a few hours into the voyage. I realized the trees were not getting any larger. Originally it seemed that the short trees, much more reminiscent of the local park in the suburb of New Jersey that I had grown up in rather than the legendary Amazon rainforest, were due to the close proximity of the port town of Yurimaguas. However, as we progressed onward through the currents of the Amazon, I had the feeling that perhaps I wasn’t in the Amazon at all but rather in a plant nursery where the latest decorative styles were being germinated for corporate offices on Wall St.

“What do you think?” A middle-aged man asked me after lunch, speaking slowly, hesitant to see if I would even respond in Spanish. I told him I was very surprised, what happened to the jungle? Where were the trees whose roots were so large that they burst out of the ground and grew into caverns large enough to live inside? Where was the height that led to the development of the multiple levels of the rainforest, something I had remembered being taught in elementary school? He chuckled, leaning his head back and closing his eyes, taking a deep breath of the air that was free of the smog of idling ships and sawdust.

“I remember when the trees were tall enough to reach the sky,” he said, looking up, “I couldn’t see above any of them and under each canopy there was a whole wilderness of animals, flying from branch to branch, swinging, singing. My father taught me the way to navigate through it, always use the machete to cut to one side,” He made the motions with his right hand, cutting through the breeze that rushed along the deck, “that way when you retrace your steps you can always follow your path. Things haven’t been that way in a long time, since the lumber companies came in whole fields have been cleared out. It started with the forests near the cities and villages and worked its way outwards, now getting to the point where the lumber companies need to take boats for twenty days through the minor river systems to find trees that are even worth harvesting.”

* *

According to a recent Wikileaks cable as much as 90% of Peru’s broad leaf mahogany, a breed that is considered endangered prompting Brazil to halt its exports and Bolivia to drastically reduce theirs, is exported illegally, much of it being done with the government’s knowledge. To top it off the United States is the purchaser of a majority of this timber, one statistic claiming that the US bought 88% of Peru’s 2005 exports. At this rate it is no surprise the Amazon is slowly converting its status into that of a suburban backyard, with its wildlife and peoples taking the hit.

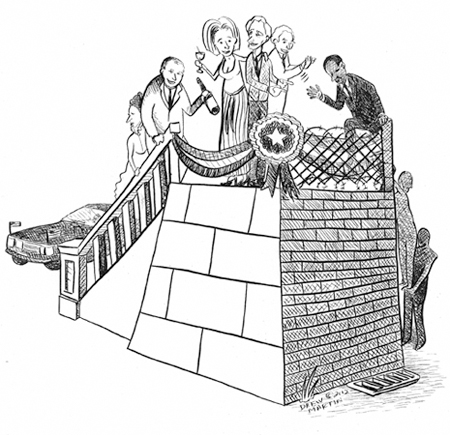

Throughout the journey the ship made frequent stops in small indigenous communities, the brown patched roofs of their houses blending into the dirt and mud on the banks of the river. Of the 15 or 20 stops they all followed the same routine. Men from the village would approach the ship carrying large bundles of plantains, handing them over to the workers on the ship in exchange for western commodities; soda, beer, and potato chips. The women and children would rush onto the ship calculating the best strategy to reach the 300 people anxiously waiting for them on top deck, sometimes dangling their arms over the edges and motioning to have articles thrown up to them, to buy and trade foodstuffs. During these moments exotic fruits, raw vegetables, cooked beef, grilled boar, and barbecued river fish were all sold to the passengers of the ship, prices ranging between $0.25 and at most $1.50. Most of the time these indigenous salespeople would leave the ship sold out, especially if the stop happened to be before mealtimes, and would use the little bits of money they had collected for purchasing the products that couldn’t be produced within the constraints of their sustainable lifestyle. At the end of the day even the most isolated communities can enjoy a glass of Coca Cola during meals.

This image seemed to me to be the most obvious example of the integration of the Peruvian Amazon into the global economy; however, the most destructive are those that are the hardest to see. The Amazon is called by many here the “lungs of the earth”, a slogan meant to give the locals pride in their communities, attract tourists, and draw attention to the enormous problems we would face globally if the Amazon was altered enough to slow down or even stop doing its job. It’s not necessary to have to explain here what happens to a living being if their lungs slowly stopped working. A recent report titled Rainforest Deforestation and Climate Change by The Environmental Defense Fund (www.edf.org) estimates that deforestation, both the removal of trees as well as the usage of cleared lands for cattle grazing and crop growing, released an equivalent of 15-35% of annual fossil fuel emissions during the 1990s. Of course, with today’s new scientific consensus on the issue it is obvious that climate change is not a linear teleology but a circular isomorphic problem and the Amazon is obviously being harmed by these logging practices in an exponential manner, besides from the loss of its aesthetic “jungle” mystery that had taken me by surprise and shocked me into attention.

The timber economy has protruded its never-ending lust for profit so deep into the jungle that its arms have reached and ensnarled areas that have never even been seen by modern man. Survival International, an organization fighting for the rights of uncontacted peoples all over the world, estimates in its numerous reports and awareness campaigns that the few remaining uncontacted tribes that call the South American Amazon their home are being blinded by the bright light of modernity by the actions of logging companies and the “representatives of the new world” that they employ and send out, axes sharpened. A radical change from the missionaries, church bureaucrats, and conquistadors that had courted the cousins of these uncontacted tribes centuries earlier, but an ironic reflection of who our society decides to send out to bring in the last patches of “barbarism” into “enlightenment”, whether we consciously choose to or not. The tribes often have to relocate, pushing them into confrontation with other tribes, and some who have chosen to make contact have described in horrific detail the fear that the monstrous stone skinned animals bring to their people as they eat away through trees leaving desolate wastelands behind them.

The ship had no set time of arrival, in a Kafkaesque way everyone seemed to know exactly where we were and how long we had traveled, though they all disagreed; I would get my updates from the man who slept to my right. On the fourth day, he was sitting up in his hammock peeling apart a papaya, motioning me over and gently tossing me a slab of its orange flesh saying, “We’ll be there tomorrow morning but I won’t see you, I’m getting off before Iquitos and I’m sure it will be around 3 or 4 in the morning.” I ate the fruit with him, and talked about his plans now that the temporary job he had on the coastal city of Piura had ended. We hurled the papaya skins over the edge of the ship from our hammocks where they stayed afloat on the river like small toy boats. He told me he was sure to be back but for now he was looking forward to spending time with his family who he hadn’t seen in 5 months. The next morning as he promised, he was gone; I had arrived in Iquitos.

A city with a dense and rich past but an uncertain future, the Plaza de Armas and surrounding blocks were filled with expensive hotels, tour guide offices touting the latest and greatest in jungle getaways, fancy restaurants serving fusions of the local cuisine, souvenir shops, and leftover ruins of the famous synagogue – a remnant from the Sephardic Jews of Morocco who arrived here during a rubber boom in the early 19th century. Marcel, the owner of the guesthouse I was staying in and supposedly a descendant of this ancient Jewish community, told me at one time Iquitos was such a popular tourist destination that there were non-stop flights from New York City. They had to be cancelled because the large planes were killing off the thousands of vultures that lived off of the leftover animal parts rotting around in the market after a long days work. “They had to clean the dead birds out of the jet engines every time! I guess the bastards got too cheap to continue” he laughed, with a thick accent and a cigarette dangling between his lips as he wiped down the ashtrays at the sink. He was a man that had an extensive knowledge of the city, living here all of his life but having attended university in Lima where he learned English and studied politics. Marcel knew everyone in Peru; either through what seemed to be flakey business ties or through the work he did with his beloved political party, Acción Popular. We passed our nights talking about Jose Carlos Mariategui, the famous Peruvian communist of the early 20th century, and what he would think of Henry, the infamous man known to everyone in Iquitos only by his first name that owned all the cargo ships and was now investing in the construction of oil tankers specially designed for river travel. He would often stumble out of his chair laughing, gasping for breath as he described Henry’s ties to the Amazonian organized crime ring, tears pouring out of his dry, bloodshot eyes.

Like any city that has had to make a switch from a semi-sustainable local economy to a tourist economy, everything in Iquitos is available to the tourist at a price. The indigenous people who still live in the outlying jungle surrounding the city will perform, sing, and dance for anyone who is willing to buy an anaconda bone bracelet afterwards. The Bora, one of the indigenous groups that I had seen perform, do not actually live the life that they put up for sale to tourists. After a further investigation, which just involved me walking through the jungle with some friends instead of leaving on the small rented motorboat we came on, I discovered what looked like a small suburban neighborhood in the larger cities of the Peruvian coasts secretly tucked behind the thick jungle foliage, with houses, plumbing, and partially paved roads.

The whole polis is organized around making money by selling goods, photo opportunities, and the shades of long forgotten cultures. Even exotic animals are traded in the marketplace of Belen. Walking up and around the fish gut stained concrete I found nets of colorful feathered birds, monkeys clawing and swinging in cages, and scaly prehistoric fish apparently able to live outside of water for three days. A booming economy of child sex work is brought to awareness by the large painting mural on the side of an old building near the main plaza reading, “No Al Turismo Sexual Infantial”. The stains of the neo-liberal drive to turn everything, and everyone, into an object to be bought or sold, traded or trashed, have penetrated deep into the river systems with lumber, oil, and tourism of all varieties.

It has become a war on two fronts in the Amazon. As if deforestation is not enough petroleum has become the new high priced commodity bubbling below the depths, and everyone is waiting on line to get a piece of the action. I remember the conversation I had with an Argentinean couple that met while living in the jungle for months organizing tribes against the exploitation of the oil companies. They were in their early twenties, coming out into the jungle because they were “tired of hearing about the change, we wanted to make the change”, as they put it. They expected an idealized life in the jungle communities, without private property, corruption, and political scandal, problems they were all too used to back home in Cordoba. “I remember the first moment reality smacked me,” the man said.

“I woke up and went to have a bite for breakfast before going off to find something to do for the day and the whole tribe was in disarray. ‘He is gone, he went with the men’ people were telling me. I was confused. It was only later that evening that I was able to piece it all together. That the man who was put in charge to lead the community, the tribal chief, had run off with about $1000 that the oil companies had paid him after selling them the community’s land. Everything that they were on, poof, gone, open for exploration, who’s next? The next few days the roads started going up, they were in perfect grids that criss-crossed through the jungle. This wasn’t because they had found anything yet, this was just for exploration, but the time was coming and the whole community was pushed over.”

The abuse is felt by everyone and resonates in all corners of the jungle. While it can manifest itself in ways that lead to local empowerment and general improvement in people’s standards of living, ideology has a way of manifesting itself in the most despicable ways. On a few instances in different jungle cities throughout Peru and Ecuador I noticed storefronts that hung swastikas in their windows. I was always stunned and confused, walking past slowly starring at the icon, never able to find anyone to ask about it. Finally I had the opportunity to confront what to me was hypocrisy when I found a small storefront in the marketplace with the symbol. The owner of the shop, which specialized in old plastic cell phone casings, explained that this is the symbol of the jungle independence movement. “We’re not racists”, he told me, shocked that I would think that,

“We are exactly what the symbol means, we are Nationalist Socialists. Our nation is the Amazon, and since the discovery of Peru until now it is being exploited while we are left out with nothing. First it was the Spanish, then it was the Americans and Europeans, and now it’s our own people, the people on the coast, the limaños, they take all of our resources to fund the country that they call Peru but where is our place in Peru. You’ve seen it, how many restaurants do you find in Lima serving cuisine from the jungle, where have you seen our music and dance, how easy is it for an Amazonian to find a job in the city, it’s impossible. They use us for everything we have and at the end we get nothing. That is why we’re standing up and saying enough is enough, we want our independence and our resources for ourselves.”

By this time the man had a few customers in his shop egging him on and throwing in examples. “We don’t get any money from the ministry of tourism!” One man in the crowd yelled, “They don’t even know what juanes or cecina is!” another woman said jokingly to me as I left the store.

The week I spent in Iquitos gave me much to think about during the six-day boat journey to Pucalpa. I was born in the United States, a country that is part of the global monster in consuming resources and causing destruction in exploring for new ways to feed the addiction. At the end of the day the events of the past two weeks are direct expressions, however negative they may be, of the way that I live at home, my family, and my friends. This is the ugly side of what it means to be developed in the 21st century and heading into a crisis of global overdevelopment while the planet reacts lurching and staggering to our human changes. While facing the challenges we today have to solve I believe it is extremely necessary to redefine what it means to be “developed”.

It did not take me long before I began to see the physical realities of my thought process. While I remembered passing many indigenous communities on the banks of the Amazon throughout my journey to Iquitos, the picture that passed in front of me as I lay in my hammock was not the same. The area of the river had flooded, taking houses, livestock, and crops with it. Every community I passed was in a different stage of shock. Some seemed to be lifeless, all human activity completely disappeared with rooftops poking through the running water. Others had adapted, with planks and bridges already in place with people running supplies to and fro; going about their daily lives. Whenever the ship stopped to unload and take on goods, workers of the ship took lists from the communities of the types of emergency supplies they would need to build back up again. Of course, this probably wouldn’t reach them for at least two weeks. Life had turned upside down.

A few days of confusion and shock from the people onboard and we were finally able to get a straight answer. Ten or twenty years ago, according to a passenger on the ship who was from one of the villages, the river had receded, giving way for about 50 feet of usable land. At first people were skeptical, thinking this was just a temporary event. “After about 5 years” he said, almost in disbelief, “we thought it was the new normal and our villages adapted, we moved closer to the river and expanded. I’m just as confused as you are, I don’t know why it came back, and after so long.” I saw him peering out over the edge of the ship everyday from then on, observing the destruction with a fixed stare on every village we passed.

On my final day aboard the ship destined for Pucalpa, I was chatting and sharing a cigarette with a 17-year-old boy heading for Lima to find a job. He stopped suddenly and starred at the shore, the land and trees slowly creeping by. I turned my head, trying to get a glimpse of what he was so mesmerized by. Finally, I had the courage to break the silence and ask, “What is it? What are you looking at?” He muttered, still in the babble of disbelief. “This is the first time I have ever seen a mountain”, he whispered to me. In the distance, climbing towards the sky, its peak lost in the grey blanket, there was something, not a mountain, at least not like the ones I had seen crossing the Andes, but a hill at least. I laughed with joy and shared in the mystery, sighing as I thought of all the things this boy was going to discover, our collective reflection as humans during 10,000 years of civilization on this planet, in the vast 9 million-person metropolis of Lima.

Riad Azar graduated from William Paterson University in 2011. He is a travelling independent journalist currently making his way from Ushuaia to New York writing about politics, society and social struggles as well as fictions. His website is www.nomadjournalism.com, and he can be reached at riadazar1@gmail.com.