The Unconscious in Social and Political Life, (London: Phoenix Publishing House 2019)

On the morning after Boris Johnson’s election as UK Prime Minister in December 2019, one television commentator predicted, correctly as it turned out, that there would now be a ‘battle of the narratives’ over the reasons for the Tories’ success.

One narrative that has so far not figured in that battle is that of psychoanalysis. Nor will this come as a great surprise to many people. While, as Eli Zaretsky has argued in an important study, ‘political Freudianism’ has often been present as a critical subterranean current within psychoanalytic thought[1], for most of its history the mainstream psychoanalytic profession has adopted a stance accurately described by one contributor to this edited collection as ‘Let the politicians fight it out – we are above such ugly hostility’. Where psychoanalysts have engaged with political issues, they have often done so by applying concepts from the consulting room directly to wider socio-political events, with results that have sometimes been frankly embarrassing. As the prominent West German psychoanalyst Alexander Mitscherlich complained at an international gathering in Vienna in 1971 with the Vietnam War raging in the background, ‘I fear that nobody is going to take us very seriously if we continue to suggest that war comes about because fathers hate their sons and want to kill them, that war is filicide…collective phenomena demand a different sort of understanding than can be acquired by treating neuroses’[2].

This volume of fourteen essays, written mainly by experienced psychoanalysts and drawn from the Political Mind Seminars which have been running at the British Psychoanalytical Society since 2015, is an attempt to develop that ‘different sort of understanding’ and to demonstrate the explanatory relevance of psychoanalysis to a world in social, political and economic turmoil. How successful is it in that aim?

Perhaps not surprisingly, given the different perspectives of the contributors and the wide range of topics covered, it is difficult to give a definitive answer to that question. A helpful starting point, however, is offered by R.D. Hinshelwood in his chapter ‘Reflection or action: and never the twain shall meet’. Echoing the view of Mitscherlich above, he observes that

There is a major problem in using psychoanalysis in political activity. The ways the individual is influenced by unconscious forces and by external social influences are essentially different, and these categories can be bridged conceptually only with some difficulty. I have been struck for some time by this conceptual divergence.

The problem which Hinshelwood identifies is evident in several chapters in the book which move, sometimes rather clunkily, between structural explanations which give due weight to ‘external social influences’ and to alternative psychoanalytic explanations which are rooted in primitive instincts and drives. Consider, as an example, the opening chapter by Philip Stokoe, which is entitled ‘Where have all the adults gone?’

To deal firstly with the title, the depiction of politicians such as Donald J. Trump as being developmentally delayed is a fair one and one that many will appreciate. It was well-captured in the huge balloon figure of Trump in nappies which floated over London as part of the protests which greeted his 2017 visit to the UK. But while that characterisation makes a useful (and humorous) polemical point it is of limited analytical value, at least in terms of politics. For one thing, who are the ‘adults’ who have left the room? Would they include Tony Blair, who led the UK into an illegal war in Iraq and promoted the neoliberal policies which have led to unprecedented levels of inequality? Or Barak Obama, who managed to deport more refugees than Trump so far has?

Secondly, how are we to explain the support for figures such as Trump and Boris Johnston amongst working-class voters? Stokoe suggests one factor contributing to that support, in the UK at least, is the generalised anxiety among people arising from the collapse of the protective structures of the post-war welfare state as a result of three decades of neoliberal policies. This is an interesting and plausible suggestion and one also taken up by other contributors. It is worth recalling, after all, that the title of first biography of the National Health Service, written in 1952 by its principal architect Aneurin Bevan, was In Place of Fear, while the system of benefits which replaced the Poor Law in the UK was called ‘social security’. Far less plausible, however, and typifying the neglect of external factors noted above, is Stokoe’s explanation of the growth of racism which accompanied the Brexit process. He suggests this was due to a combination of ‘innate, unconscious’ racism on the one hand and on the other, the fact that, ‘from early on, we all carry an image of a group of strangers that threaten our survival’. From such an explanation, one would never guess that both prior to and during the Brexit referendum, politicians such as the then Home Secretary (and later Prime Minister) Theresa May consciously whipped up what was officially described as ‘a hostile environment’ for refugees and asylum seekers. May (at that time, incidentally, still a Remain supporter) was also responsible for the Windrush scandal which saw thousands of long-term British residents originally from the Caribbean being refused treatment on the NHS and in many cases deported to their ‘home’ country. Here psychoanalytic explanations let such officially sponsored state racism off the hook.

If a neglect of material and structural factors weakens some of the contributions to this book, then conversely the stronger chapters are those which come closer to achieving a fruitful synthesis of structural analysis and psychoanalytic understandings. Thus, in what is probably the most sociological contribution, Michael Rustin’s chapter focuses ‘less on the role of political leaders and more on the conditions which have enabled them to gain large-scale support’. He links the current ‘structures of feeling’ within society, the collective mood of anxiety and resentment, to factors such as the global financial crash of 2008, the wars in Iraq, Afghanistan and elsewhere and the refugee crisis of recent years. Elsewhere, David Bell paints a vivid picture both of the way in which neoliberal policies and austerity policies in recent decades have undermined good psychiatric care and also of how a basic human fear of dependence has been exploited by right-wing politicians to make mental health ‘recovery’ a personal duty and responsibility (albeit that he is rather too uncritical of the limitations of traditional psychiatric services which have been the object of a powerful critique in recent years by critical psychiatrists, psychologists and service users). And in an eloquent defence of psychoanalysis as ‘an ethic of listening’, Jonathan Sklar makes the case for a psychoanalytic practice based on ‘the ability to tolerate the other without allowing domination, and at the same time as recognising complexity’, in sharp contrast to the low-cost, CBT-based quick fixes which are often all that are currently on offer from public mental health services, in the UK at least.

As critics of psychoanalysis will be quick to point out of course, the highly democratic and empowering account of psychoanalysis presented by Sklar and other contributors often bears little resemblance to the realities of psychoanalytic practice, past and present. One reason for this is suggested by Stokoe in his discussion of ‘the trap’. ‘The trap’, he suggests ‘is the expertise that nearly all human beings have about understanding other human beings: we are very good at reading other people’s unconscious…The only unconscious we cannot read is our own’. In principle the lengthy personal training analyses which psychoanalysts undergo should enable them, if not to overcome their own ‘blind spots’ and prejudices, then at least to be aware of them and prevent their interfering with the process of analysis. In reality, however, what the history of the psychoanalytic profession shows is the extent to which its exponents have been shaped by what Marx called ‘the ruling ideas’ in society. So, for example, as Dagmar Herzog notes in her excellent Cold War Freud: Psychoanalysis in an Age of Catastrophes (2017), before the early 1980s some 500 psychoanalytic essays and books had been written on the topic of homosexuality. Of these, less than half a dozen clamed homosexuality might be part of a satisfactory psychic organization (Freud himself, of course, had a more nuanced view).

In the same way, while several of the chapters in this book contain useful insights into the impact of neoliberal social and economic policies on people’s emotional lives, running through many is a kind of left-liberal, Guardian reader ‘common sense’ that is itself seldom the subject of critical reflection. This sees the EU, for example as unequivocally a ‘good thing’, despite its institutions being responsible for the immiseration of the Greek working class through the imposition of brutal austerity and for the deaths of thousands of refugees in the Mediterranean. Brexit is deplored but rarely seen as an understandable response to what the journalist Will Hutton has called ‘shit-life syndrome’, a reality-based sense of despair which, in the absence of a real alternative, can lead in right-wing or racist directions. And in what is one of the most powerful and moving chapters in the book, Fakhry Davids shows that, for all their training and cultivation of reflectiveness, psychoanalysts are no more likely than the rest of the population to show a deeper understanding of Islamophobia or the plight of the Palestinians or the distinction between anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism.

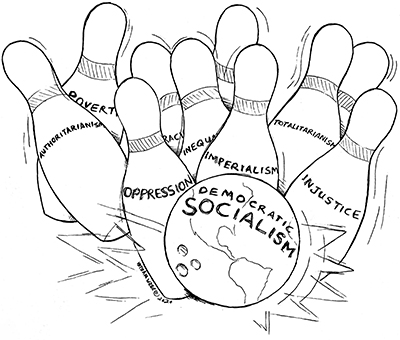

To return to the problem identified by Hinshelwood, for this reviewer at least concepts usually associated with the classical Marxist tradition, such as exploitation, oppression, alienation, class struggle, solidarity, are of considerably greater explanatory value in making sense of the world of 21st century neoliberal capitalism than are those of psychoanalysis. But what the more successful chapters in this collection do show is that, among other things, psychoanalytic insights can sometimes provide ideological support for the political strategies necessary to combat exploitation and oppression and build solidarity. To end with one such example, Sklar skilfully employs the notion of the ‘double attack’ experienced by child victims of sexual abuse – the initial assault and then the conscious minimising of that assault or the injunction to remain silent – to make sense of the experience of the racist abuse, including banana throwing, experienced by black English footballers at a game in Serbia in 2012. To their credit the other English players refused to collude with any suggestion that this was ‘just a bit of fun’ and stood by their comrade. As Sklar notes:

We can see that the behaviour of the group has a profound significance – that is whether they join in the attack or stay quietly neutral, as if it is nothing to do with them, or whether a critical number stand up with the victim against the double attack. Racism, anti-Semitism and homophobia do not work in an atmosphere in which the premises of the attack are strongly rejected.

While such insights are not a substitute for political analysis, it is nevertheless encouraging to see a practising psychoanalyst drawing on his professional experience to reinforce the importance of collective action against racism in all its forms and to emphasise the need for a ‘critical number’ of us to stand in solidarity with the victims of racism. At a time when the threat from the far right across the globe is greater than it has been at any time since the 1930s, that kind of ideological support from psychoanalysis is both timely and welcome.

Iain Ferguson is author of Politics of the Mind: Marxism and Mental Distress (Bookmarks, 2017)

[1] E. Zaretsky (2017) Political Freud: a History, New York: Columbia University Press

[2] Quoted in D. Herzog (2017) Cold War Freud: Psychoanalysis in an Age of Catastrophes, Cambridge University Press, p4.