Why Democracy and Socialism Need Anti-Racist Socialist Feminism

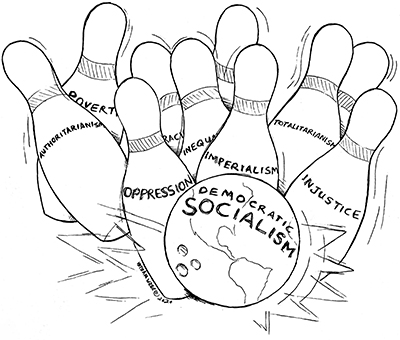

Amidst the right wing white supremacist challenges to democracy resides both a new embrace of socialism and its vilification. Amidst this cacophony exists the rare possibility of radicalizing the meaning of democracy and, with it, socialism at a time where the meaning of each is fractious and also rich with possibility.

I imagine a loving, socialist, anti-racist feminism. My wish is to open and enlarge the possibilities for seeing more creatively, while using and being rooted in the historical limits and possibilities that can be newly mobilized.

Democracy has never been emancipatory—meaning democratic enough. And socialism is never socialist—egalitarian enough. Neither can fully actualize itself without the radical stance of the other. And neither can be attained without a robust anti-racist and feminist agenda.

After four decades of anti-racist socialist feminist activism, I am more committed than ever to a socialism that is fully democratic but this necessitates an end to sexual and racist violence that nurtures economic violence. My kind of socialism demands an end to economic exploitation and the inequities of wealth and power derivative of the selfishness of profit-making. And this necessitates the dismantling of white supremacist misogyny that structures all profit, from chattel slavery to the carceral state. Much of this argument about the foundational role of chattel slavery in everything U.S. has recently been spelled out in the acclaimed New York Times project “1619.”

I argued early on for a socialist feminism—that capitalism was always mutually dependent on patriarchy, and therefore socialism would have to be feminist as well as Marxist.[1] I have further specified this argument, clarifying that patriarchy always has been white supremacist, so that socialism needed to be anti-racist and abolitionist of racist and gender hierarchies and inequities.[2]Neither democracy nor socialism has been fully representative and inclusive of the gender and racial varieties of humanity.

In order to be inclusive of humanity, socialism must become fully democratic, free and/or liberatory. Liberation is more radical than democracy as people of color and the poor have known it—liberation points to the inadequacies and exclusions of democracy as it has been lived. Liberation requires an end to patriarchal racism and capitalism, while democracy often has protected aspects of each structural system.

In order to be democratic, socialism must dismantle the racist and misogynist structuring of the division of labor, both waged and domestic. This requires an explicit assault on white supremacy and its intimate structuring of sexual violence. Their interdependence with capitalism reproduces power systems that are most often hidden and occluded. This naming of misogynist racism allows it to be seen, and problematized for restructuring.

As such, socialism has the potential to become radically democratic and liberatory. This specified critique directs us to look at the newest divisions and structures of power and profit across the globe creating complex transnational patriarchal family structures. The poorest of the poor today are women of color as they become the newest migrants and refugees—trying to escape sexual violence as they do the domestic and familial labor of the rich.

Sexual violence, embedded both in the workplace and domestic labor in the home, glues the entire power nexus together. There can be no liberatory democracy with sexual violation, sexual harassment and rape. Each of these violations is threaded through the structures of racial segregation, racial violence, and racial exploitation. S/exploitation is endemic and structural. Hence, no socialism can be democratic enough without being anti-racist and feminist. In its naming, socialism singularly focuses on economic exploitation and occludes its multiple underpinnings and tentacles of power

There is more than one kind of democracy, although democracy is most often equated with its liberal, bourgeois and Western forms. This particular solipsism hides the racist and misogynist class-based underbelly of bourgeois and liberal structures. Socialism is under siege today by liberals and right-wing conservatives, but not for its exclusivity. The critique charges that there will be a mind-numbing egalitarianism of mediocrity and sameness, with no individuality. In this instance, bourgeois individualism is equated with individuality. A liberatory socialism dis-allows the selfishness and greed of bourgeois individualism, but nurtures the individuality of the social being. The Eastern European revolutions of 1989 only heightened the confusion that democracy needed to be Western and liberal.

Democracy did not work out for the revolutions of 1989. People in the former Soviet Union wanted their lives to be like the rich Western model, not the South Bronx. Socialist revolutions abided women’s equality and bodily autonomy until they needed an uptick in the population/labor force. Abortion became illegal for too long in Russia after the 1917 revolution. Post-’89, women were made equal, which meant they entered the labor force alongside all they already did, leading to the triple day of work for most women: wage labor, domestic labor, and consumer labor. Oppression—the stealing of labor in unpaid form—underpinned this newly socialist exploitative system.

After the fall of the Soviet Union I found the term “socialist” more problematic than helpful. The promise of (Western) democracy became further compromised with the inequities of capitalism. In this period—the 1990’s—I stopped identifying as a socialist, because it no longer was helpful in naming the critique of capital accumulation as a core commitment.

By never actualizing full equality, democracy has not worked out for the U.S. civil rights and women’s movements. Democracy is not working for the people in Philippines, Venezuela, India, Turkey and Poland or the U.S., as authoritarians and despots take over.

It is interesting to now once again ponder the meaning of democratic socialism, or socialist democracy in the present right-wing context of the U.S. and much of the globe. Why wonder about the relationship between democracy and socialism in 2019? Socialism has new legitimacy, as several U.S. presidential hopefuls either identify themselves as such or borrow socialist elements for their platforms. And there is now broad support for programs such as “Medicare for All,” often described as socialist. And, of course, Trump takes every opportunity to say that the U.S. will never become socialist, making the concept intriguing to many voters who detest all that he represents.

Given the context of the 2020 presidential election and the identification of Trump as anti-democratic, authoritarian, racist, and misogynist, socialism as an idea has new efficacy. It looks kinder and fairer. It looks more like democracy than Trump. I am not sure you can legitimize socialism with democracy in this fashion. But given the present presidential dialogues, there is new efficacy for using this radical possibility to jump-start a radicalizing of democracy with socialism.

Although I do not think radical enough notions of democracy or socialism currently exist, I do think that extant partial politicized fragments may help show the way towards a vision of a radicalized democratic socialism. Bourgeois, liberal democracy has never been socialist enough, and yet it instigates new struggles towards inclusivity: peoples of every color, and gender, and sexual identity.

2019-20 is a time of political and economic upheaval where nations have been exploded by global capital, and white supremacy and its misogynist base has been exposed by the Black and Brown world. Nations appear powerless against global demands, and yet nation states sputter forward—looking inept and yet doing great harm. So, I have more questions than I have answers about political paths to take in this period.

I once thought that the struggle for liberal democracy might radicalize itself by its own promissory beyond its class, race and gender structural constraints. But I no longer think that liberal democracy can deliver on socialist democracy, so to speak. Neo-liberalism has been the response to the most democratic/egalitarian demands of the civil rights and women’s movements. Neocons and neoliberals argued that democracy had become too democratic and therefore ungovernable. Democracy for the people has been under relentless attack in the U.S. since the mid-1970’s.

But as the rich have gotten richer and the poor and middle classes feel the pain, this trend may be changing. These newest excesses expose the very power that the powerful wish to keep hidden. And these exposures—of and by people of color as a majority force, and the changed constellation of white supremacy and its excessive economic greed, may just lay the basis for a liberatory socialist democracy.

A liberatory model of socialism that demands abolition of profit and the color line and gender hierarchies may already be in process, and needs nurturing. It is quite possible that a liberatory socialism will emerge from the newest constituencies—especially women of color in the present struggles of the day. Let us look to the future, rather than the past, in order to develop these initial imaginings.

It does not help to assume that political identities and structures are static and unchanging. The modes of production continue to change with new global arrangements and cyber technologies that don’t recognize old borders of countries or public and private realms. So control of the modes of producing/exploiting requires new ways of seeing and knowing where power, specifically economic class power is located. There are new layers of mystification and protection that keeps the power grid brilliantly functional.

Socialism is an economic system based on human needs rather than profit motives. Profit negates the humanity of production and the new ways to exploit labor are endless. So I know that socialism cannot allow the stealing of labor in any of its forms: economic, sexual, gendered, raced, etc. The hierarchies of labor divisions must be dismantled and repaired with reparative models. “Equal pay” as a feminist slogan is no longer sufficient.

Democracy has morphed from liberal, to neo-liberal, to fascistic. None of these varieties can assist socialism. If we are going to use the left-overs of the present war on socialism and democracy as a starting point for a liberatory socialism, we might mobilize around: taxing the rich; protecting the climate; providing housing to all in need; offering free access to health care and day care and the care of loved ones; nurturing healthy environments; providing a guaranteed income; ending exploitative profit-driven labor and consumerism; and so forth. Such a program would necessitate a rethinking of labor and its relationship to knowledge, robotics and AI (artificial intelligence), and a plan for the organization of everyday labor and the production of needed goods without dehumanizing jobs.

Would this be more democratic? Yes. Would this be socialist? It would be a start towards socialism. I am asking for a process that will define itself out of the options that are created out of the struggles to find a more humane way to sustain the planet and its people. I agree with Rosa Luxemburg that we need theory to guide our practice; but our practice must also guide our theory, and naming/s.

There is no established checklist that declares “socialism exists.” How do you take control of the modes of production when systems of production sometimes no longer have “modes” that are recognizable? The new constructions of power, exploitation and oppression require new imaginings of socialism/s and anti-racisms and feminism/s. When present day progressive thinking so often privileges economic justice and the problem as one of “class,” too much else that defines the hierarchies of class is silenced and hidden. This repetitive problem may explain the insufficiency of past socialist struggles.

When I think of the long history of struggle about the meaning/s of the welfare state, the debates between reform and revolution, the severing of articulated demands like the Green New Deal that underline the democratizing of socialism—I see a long difficult process of radicalizing democratic struggle.

I want to embrace the elasticity of political identities by making sure that their silent specificities—often of exclusion by silence—are named explicitly. The more specified the notion of democracy and socialism, the more inclusive and universal their meaning. So the democracy must be anti-racist and feminist and anti-capitalist.

I continue to think that this may be a rare and unique moment for radicalizing socialism towards egalitarianism and radical democracy, because of the traumatic and punishing level of hunger, desperation, and climate crisis for a majority of the globe. The U.S. is more racially diverse than ever before. Huge numbers of women of color are super-exploited in the labor force, while their daily domestic and consumer labor remains unpaid and completely stolen. One cannot fix this oppressive exploitation without addressing its racist and misogynist structuring.

Not surprisingly, women of color, especially Black women, are the most mobilized and radical voters today. Stacey Abrams, who came close to winning the 2018 governor’s race in Georgia, is now committing her full political power and attention to addressing voter suppression. Other women of color, especially recently elected Democratic women Ayanna Pressley, Rashida Tlaib, Ihan Omar and Alexandria Ocasio Cortez, lead a radical electoral assault today while embracing socialism, whatever that might particularly mean to each of them. Trump has singled these WOC out for special ridicule, calling them “the Squad” and telling these American born elected officials, except for Omar, to return to their crisis-ridden countries.

These four WOC bring a serious indictment to the neoliberal Democrats. They stand with and for a progressive socialism—one that practices egalitarian commitments—a Green New Deal, pro-Palestinian politics, and a guaranteed income. It is no surprise that these women are supported by, and come out of and represent, progressive movements of and for democratic socialism and socialist democrats.

It may now be possible to take the electoral politics of socialism and radicalize it beyond the usual liberal or welfare state conception. It may be possible to use the serious indictment that the “Squad” has leveled against neoliberalism to build a radical electoral politics that hopefully can defeat Trump, and lay the basis for an extra-legal/reform movement towards a revolutionary anti-racist socialist feminism.

That the concept of “Medicare for All” has taken hold in the 2020 election cycle is a rare offering, and must not be ignored. Activists must use the attacks on socialized medicine to make clear why socialism and curbing private profits and its excesses are needed. Right wing Republicans jab away at Democrats as socialists when most of them are hardly either. But why not use this entry point to demand a radical politics of health care that includes food and shelter for all, while embracing the need for socialized medicine? Use this politics of the possible, while also demanding the seemingly impossible radicalized notion of an abolitionist socialist feminism.

“Health care for all” is a radical demand because it focuses on our bodies; and bodies are always a truth-telling site. Organize from here to fight for a socialism that is not white supremacist and misogynist. Sickness and illness could not be more democratic in that everyone is susceptible; and yet our options once ill are gravely unequal and punishing.

In this vicious right wing moment infecting the globe, I stand firmly committed to a radically liberatory socialism while recognizing that the revolution we need is unknown to me at this time. So I embrace as much love and integrity and imagination as is possible, to see what the complexity of a democratic anti-racist socialist feminism might look like. Maybe we might get it right this next time.

Struggles are always defined and limited by existing conditions, although they do not have to be circumscribed to these limits. So for this moment, let us make radical liberals and electoral radicals into radical socialists. It should be no surprise that out of the shifts and upheavals it is young women of color showing the possibility of a radically democratic politics.

This promise of a radically democratic socialism and a radically socialist democracy lies in the liberatory practices and demands of WOC that may allow for an abolitionist socialist feminism, one that is truly democratic, and hopefully liberatory.

Notes

[1] In Capitalist Patriarchy and the Case for Socialist Feminism, ed. Zillah Eisenstein, Monthly Review Press, 1979.

[2] In my book Abolitionist Socialist Feminism: Radicalizing the Next Revolution, Monthly Review Press, 2019.