What is Genocide?

Most discussions regarding what has become by now an almost chronic question: “what is genocide?” tend to focus on the epistemological aspect of this question. This question is understood as an inquiry regarding the adequacy of a specific analytic concept to a specific factual pattern of events.

This recurring pattern is supposedly traceable in a certain – yet highly contested – canon of historical situations, such as: the Nazi liquidation of the European Jewry during the Second World War; the destruction of the Ottoman Armenian populations by the Young Turks regime during the First World War; or the annihilation of alleged Tutsis by the Hutu Power in 1994 Rwanda. Is genocide, for example as defined by the 1948 UN convention on the prevention and punishment of the crime genocide, a good enough analytic description of what actually happened in those historical situations? Do any of the other definitions of genocide, suggested over the years, enable a better analytic description of such events?

Obviously such epistemological inquiries are not naïve in the sense of assuming an independent historical reality – an already structured constellation of hard facts, which was objectively out there as such – waiting for us to adjust and fine-tune our analytical concepts to the point of perfect accuracy. There is a deep interdependence between the formation of analytical concepts and the uncovering, construction and interpretation of historical hard facts. The very canon of possibly-genocidal historical situations is paradoxically both constituted by the definition of genocide and is also the empirical basis from which one is supposed to extract such a definition. This means that such epistemological inquiries are in a way an endless reciprocal movement between the factual and the conceptual, each underpinned by the other and yet also transcending the other, hence perpetuating the process further.

It is for this very reason that the definition of genocide in the UN genocide convention cannot be a very good definition of the phenomenon concerned. One could hardly argue that Raphael Lemkin – who originally proposed the term – or the various drafters of the convention, were somehow miraculously able to bring the factual data available to them at the time and the conceptual pattern they extracted from it, to such a perfect accord that could not be surpassed ever since. In the sixty years that passed since the adoption of the UN genocide convention, an avalanche of historical, anthropological, political, sociological and physiological studies on genocidal events were published. In view of all these new insights on the phenomenon concerned, certain conceptual modifications to the definition of genocide were indeed already called for. In fact, some have already argued, that the way we understand what had actually happened in the historical situations concerned has been so revised by now, that the very foundational components of the concept of genocide are no longer applicable. From an epistemological perspective, we can no longer narrate or analyze such historical situations in terms of a concrete collective actor (“the perpetrators”) that is intentionally perpetrating a certain systematic act (“the genocide”) to an identifiable pre-existing group of victims (the “victims”) in front of by-standing third parties (“the by-standers”). Far from corresponding to the grid that the concept of genocide presupposes, some have suggested that the historical situations concerned should rather be described in terms of various groups of perpetrators that are targeting various groups of victims because of various motivations and by means of various kinds of violence.

Such defused and micro-level oriented descriptions may indeed be far closer to the detailed way in which things actually happened; yet they do not merit abandoning the concept of genocide or its re-conceptualization. We should note that the concept of genocide – originally coined as a legal concept – is not simply referential (i.e., describing states of events), but rather what the philosopher of language J. L. Austin influentially termed: performative. The concept of genocide is performative in the sense that rather than describing the world as it is, it is meant to do something in the world. The concept of genocide is meant to shoehorn a complex reality into a rigid framework that will enable a certain processing of what happened and in reaction to what happened. This was in fact intended to prevent such a phenomenon – genocide – from happening again. A proper concept of genocide should surface and accentuate certain aspects and dynamics in a given historical situation, so as to facilitate the tracing of culpable agents, the delimitation of the concrete criminal actions and the clear identification of their victims.

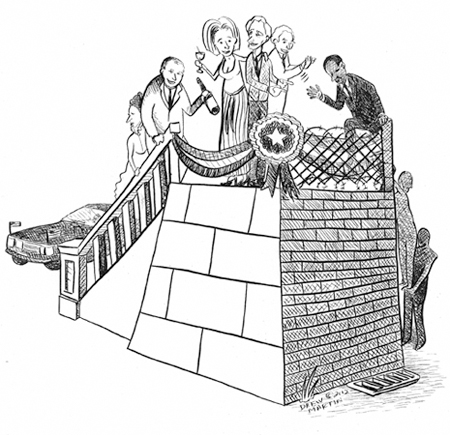

Certain definitions of genocide, though suppressing significant parts of what actually happened – crudely homogenizing a rather diverse aggregation of agents, actions and victims into a unified pattern – may nevertheless be preferable to definitions that open up a far richer and detailed description of the concerned events. A proper concept of genocide makes for an efficient narrowing of vision – a tunnel vision that will bring into sharp focus certain limited aspects of an otherwise far more complex and unwieldy reality. The conceptualization of genocide was meant to make that phenomenon legible in the sense used by the political anthropologist James C. Scott. By making a phenomenon legible, Scott means legible to the state – legible so as to enable the state to govern and administer the concerned phenomenon by means of law. Shoehorning the inexhaustible multitude of details actually found in a phenomenon into a rigid grid may be the only way to make it administrable, regulatable and controllable.

However, in the case of the conceptualization of genocide, the phenomenon concerned was not made legible to the state – it was made legible to that rather contested entity referred as the International Community. The problem was – and still is – that the exact meaning of making a certain phenomenon legible to the International Community is an essentially contested matter. How much should the International Community be allowed to govern, regulate and monitor certain situations and patterns of conduct? We may describe the drafting of the genocide convention as a far from trivial attempt to properly describe the phenomenon concerned so as to make it legible to the International Community, while at the same time still struggling to understand how far the drafting countries were willing to make their internal affairs internationally legible.

The above means that the epistemological aspects of the question: “what is genocide?” are strictly subjected to the political aspects of this question. Hence, we should not be asking if the exact difference that the convention established between acts that do constitute genocide and acts that are “less than genocide” is accurate or false. Instead we should ask other kinds of questions: Why was such a difference deemed necessary to create in 1946? Who benefited from its establishment? What did such a difference facilitate? What did it prevent?

Why did countries (55 of them in 1946 and 58 by 1948) agree to create and than actually adopt the UN genocide convention, circumscribing the Westphalian ideal of absolute state sovereignty? Why would any government favor establishing an effective independent international authority, the sole purpose of which is to constrain its domestic sovereignty in such an unprecedentedly invasive manner? By creating and ratifying the genocide convention states did not just give away a certain portion of their internal sovereignty. They also committed themselves to actively intervene under certain circumstances in the internal business of other countries even if they do not have any direct interest in doing so, and even if doing so will be against their direct interests. It may well be argued that the willingness of states to provide in certain situations resources (whether manpower, equipment or funds) for dealing with problems that may not affect or concern them at all, is just as puzzling as their willingness to allow other states to intervene in their own internal business. Why than would states subject themselves to sacrifice valuable resources in order to address the problems of others?

There is no single answer here of course – a single explanation applying to all states. Different states under different circumstances did so for different reasons. The obvious first explanation will suggest that states participated in the drafting of the convention and adopted it because they were coerced into doing so – compelled to do so by great powers, which externalize their ideology. The tightening tensions of the emerging cold war were of course manifested in the drafting discussions, as each of the blocks tried to word the convention in a way that will express its own ideological sensitivities and interests. A characteristic statement in this regard was for example made by the Polish representative who argued during the drafting discussions of the convention held in the Sixth committee of the General assembly that: “if the inclusion of the protection of man in the political field was being considered, I would ask why the protection of man in the economic field should not also be included. Poor working conditions, starvation wages or lack of labor legislation, were also ways of annihilating people”. As the statement of the Polish representative exemplifies, the two blocks were equally on guard, cautioning against the other side’s attempts to harness the convention for the dissemination of its ideology. As opposed to such ideological excesses, it was assumed that there is a certain obvious to all, core idea concerning what was that phenomenon termed genocide, and how should the convention prevent it from happening and punish its perpetrators.

A second explanation may hence suggest that states participated in the drafting of the convention and adopted it because they were normatively persuaded into doing so – swayed by the overpowering ideological and normative appeal of the values that underlay it. As the American representative stated in the opening of the convention drafting discussions in the General assembly’s Sixth committee: “having regard to the troubled state of the world it was essential that the convention should be adopted as soon as possible, before the memory of the barbarous crimes which had been committed faded from the minds of men”.

Having said that, the states that took part in the drafting of the genocide convention needed to define the concept of genocide in a way that will on the one hand apply to those notorious and spectacular perpetrations of the Axis states before and during the war, while on the other hand clearly not apply to any of the systematic attacks on civilians or to the populations engineering policies that were sponsored by the Allies during and after the war. Hence the drafting states sharpened and radicalized a notion of an “obvious difference” allegedly separating acts of genocide from any other seemingly bordering acts. This notion of an obvious difference was constructed by stressing the peculiarities of Nazi ideology, innovative industrialization of murdering and even the spectacular plethora of perversions that the Nazi era indeed cultivated. Responding to this tendency during the drafting discussions, the Chinese representative drew the committee’s attention to: “the fact that Japan had committed numerous acts of that kind of genocide [genocide committed through the use of narcotics] against the Chinese population. If those acts were not as spectacular as Hitlerite killings in gas-chambers, their effect had been no less destructive. In drawing up a convention of universal scope it was appropriate to keep in mind not only the atrocities committed by Nazis and Fascists, but also the horrible crimes of which the Japanese had been guilty in China”. The Venezuelan representative also protested against the over identification of genocide with the spectacular perpetrations of the Nazis: “the human conscience was particularly shocked by those acts of genocide which constituted mass murder […] yet less spectacular crimes should not be overlooked and the concept of genocide should extend to the inclusion of acts less terrible in themselves but resulting ‘in great losses to humanity in the form of cultural and other contributions” for which it was indebted to the destroyed group'”.

And indeed, the Venezuelan representative seemed to express in this statement the original intentions of Raphael Lemkin himself. Lemkin intended genocide to mean the metaphorically defined murdering of the genos itself – the effective annihilation of that certain collective wholeness that though somewhat elusive so fundamentally distinguishes a genos from any mere aggregation of individuals (such that may be found for example in a refugee camp, or in a busy airport terminal). And yet, the final version of the convention defined genocide as the intentional annihilation of a national, ethnic, racial or religious group, exclusively by means of physically murdering its members. During the drafting process, acts, that while resulting in the complete shattering the group’s collective existence, do not bring about the physical death of its members (such as: forced mass transfers of populations, destruction of identity defining assets, preventing the group members from practicing their identity sustaining practices), were excluded.

This is not very surprising given that the Allies shouldered the forced transfer of around twenty million people in Southern, Central and Eastern Europe between 1945 and 1955. Between 1947 and 1951 around 7,000,000 people were uprooted and transferred from India to Pakistan and about the same number were uprooted and transferred from Pakistan to India. And there were still other cases of uprooting and mass transfers of populations that took place in those years. The lion share of all these brutal transfers of populations was perpetuated in the very same days as the convention was being drafted. Reference to acts such as uprooting and forced transfer of populations, were already suggested in the very first draft proposed by the delegation of Saudi Arabia in 1946. In the Saudi draft, one of the acts constituting genocide was the: “Planned disintegration of the political social or economic structure of a group, people or nation”. And yet although several references to such acts were proposed over the following two years (interestingly mostly by Muslim countries), they were not included in the convention.

It is in light of such exclusions that we turn to a third and final explanation. An explanation suggesting that the states participated in the drafting of the convention and adopted in order to hide behind it all the agreements and institutions they were not interested – or no longer interested in creating or joining. The drafting of the UN genocide convention was part of the establishment of a very certain international regime of rights, created in the aftermath of the Second World War. The Whiggish take on the matter argues that the drawing and the adoption of the UN genocide convention, with all its faults and shortcomings, constituted a step forward in humanity’s civilizing process – stabilizing a consensual definition for an essentially contested concept. It expressed the modest yet unprecedented willingness of independent states to give away a certain portion of their sovereignty by subjecting themselves to a carefully phrased higher moral standard. Given all that was perpetrated during the Second World War, it really seems that the creation of the UN genocide convention was the least humanity could do, if being human was to retain any of its core meaning.

Yet what if this is indeed all that the drawing of UN genocide convention really was – literally the least that the international community could do? What if, the creation of the UN genocide convention was also a way to practically waive and veil all that the states were not willing to commit themselves to avoid doing? Rather than a long over-due element in the linear progression of the international rule of law, the creation of the genocide convention was part of the reconstructive dismantling of the former – evidentially dysfunctional – international regime of collective minorities’ rights, established after the First World War.

Since the end of the 1930s, all were unanimous in arguing that the inter-war international regime of collective minorities’ rights failed completely. Commentators repeatedly stressed the way Nazi Germany (and even certain elements within the Weimar Republic before hand) abused the international protection of minorities in order to mobilize into so called “fifth columns”, the German minorities in Germany’s neighboring countries. Yet those commentators tended to down-volume the fact that the inter-war minorities’ protection system was also not universal at all. It applied only to some of the defeated or the newly created states. The system was clearly damaged by its undisguised discriminatory nature. The states bound by it felt themselves humiliated – robbed of absolute sovereignty over their own territory and populations. Nevertheless, any attempt to transform international Minorities’ protection system into a truly universal regime, by which all “civilized nations” were bound, was decisively aborted by the great powers.

After the Second World War, Britain, France, the US or the USSR were still very unwilling to commit themselves to any minorities’ protection system. Hence, in the name of establishing a truly universal regime of rights, the underlying principle of collective rights was replaced by a principle of individual human rights. The celebrated rise of the international protection of individual human rights, codified in the UN 1948 declaration of human rights, effectively camouflaged the disappearance of the inter-war international protection of collective minorities’ rights.

And yet, distinctively referring to the annihilation of the genos itself rather than to the individuals composing it (which are protected by other concept such as crimes against humanity and war crimes), the genocide convention clearly emanated from the former principle of collective rights. As such, it should be interpreted as a remnant of that debased principle. The genocide convention is the minimal protection of collective rights that the post-war international system was still willing to provide: the right of a collectivity not to be annihilated by means of the physical destruction of its members. Having said that, since the collective existence of human groups could still be dismantled by many other means (such as the forced displacement of the group’s members or their forced assimilation into another group) one may rightly wonder: which right exactly was actually protected by the genocide convention? Only by assuming, against all existing historical evidence, that the mere physical survival of the group’s members is sufficient to enable the reconstruction of its shattered collective existence, can the genocide convention be interpreted as truly protecting the right of national, ethnic, religious or racial groups to exist.