Leadership Beyond Presidential Power: A Tribute to Jimmy Carter

My Rationale for Paying Tribute to Leaders

Over the years, I have paid tribute in differing ways to national and global leaders. Even as I wrote about these leaders, I posed to myself the question why I dared write about people who were so important and well known that it did not need me to promote their legacies. What value would my tribute add to their immortal profiles? I concluded that my recollections were about my personal connections with those individuals, and to that extent, the tributes were about both the persons I paid tribute to and me. I have always been mindful about the risks involved in this ambiguity. But my hope has been that in a modest way, my personal connection with those individuals might shed some added light to understanding them as human beings with laudable merits, albeit with some human shortcomings. It is with these considerations in mind that I have the pleasure and honor of paying tribute to President Jimmy Carter as I knew him as a global leader and an individual human being.

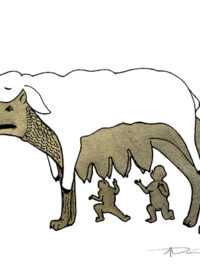

Jimmy Carter and Kofi Annan in South Sudan. Photo by Ranjit Bhaskar

President Carter as a Partner in Search of Peace

Although I had numerous interactions with President Carter over the years, I will focus on a few occasions which have particular significance to my remembering him. One event stands out as the core of my relations with him over the years. We were at a meeting in the United Kingdom in some historic venue to discuss conditions in Africa. When President Carter arrived, we were all lined up to be introduced to him. When the introduction reached me, Carter surprised us all by saying, “You do not introduce Francis to me. I have known him for almost as long as I have known Rosalynn.” Of course, the remark was complimentary and was meant as such, but I also felt it discomforting for the President to compare me with his lifelong beloved Partner-Spouce. The President went on to say, “Francis and I have been working together for a long time to end the war in Sudan.” I interjected, “And Mr. President, the degree of our success shows in the way the war continues.” President Carter in turn responded, “But we never give up.” I fully shared that sentiment.

First Encounter with Carter and the Camp David Accords

I first met President Carter during President Jaafar Nimeiri’s visit to Washington. I had been appointed Minister of State for Foreign Affairs in 1976 after having served as Ambassador in Washington. I began to hear much about Jimmy Carter shortly after his election during the African American Conference in Lesotho in 1976 when many participants in the conference, among them Andrew Young, soon to be US Ambassador and the Permanent Representative to the UN, had much to say about the President Elect. I then met him in person shortly after the conclusion of the Camp David Accords between Egypt and Israel in September 1977. Nimeiri had sent me to prepare for his visit to Washington, being his first visit under Carter’s presidency and second visit after the first successful visit during Gerald Ford’s presidency that I had arranged at the tail end of my term as Ambassador to the US. The Camp David Accords were concluded during Nimeiri’s flight to Washington.

After he settled into Blair House, the Official Guest Quarters of the US President, members of the Sudanese delegation, including Rasheed El-Tahir Bakr, Vice President and Foreign Minister, after Dr. Mansour Khalid, and the President’s Press Advisor, left. Our ambassador, Omer Salih Eissa, and I stayed with the President. Nimeiri then handed me a handwritten note to read. The note which was in Arabic was a press statement the Foreign Minister and the Press Advisor proposed for the President to make in response to the Camp David Accords. The statement was a rejection of the Accords in solidarity with the position of the Arab League. I could not believe what I was reading.

Before I elaborate on my reaction to the statement, it is important to provide the background to the positive evolution in our bilateral relations with the US from a very low point to a remarkable level of cordiality. The proposed rejection of the Camp David Accords would contradict and reverse all that we had achieved in improving our relations with the United States. The following long detour may be a distraction from our focus on the peacemaker role of President Carter, but it is essential to appreciating the long journey in cultivating close ties with the United States which would make the proposed rejection of the Camp David Accords incongruent to that monumental achievement.

The Challenges of my Mission as Ambassador to Washington

I had just been successful in reversing a near-break in our bilateral relations with the US in the wake of the Palestinian Black September terrorist assassination of the American diplomats, Ambassador Cloe Noel and George Curtis Moore, along with other Western diplomats, at the Saudi Arabian Ambassador’s residence on March 1, 1973. The nation was celebrating in Juba, the capital of South Sudan regional government, the first anniversary of the 1972 Addis Ababa Agreement. I was then Ambassador to the Nordic Countries and attending the celebrations. The Foreign Minister, Dr. Mansour Khalid, asked me to draft condolence messages to the countries of the victims. President Nimeiri, outraged by what was popularly seen as an Arab affront to the Addis Ababa Agreement with the non-Arab South Sudan, vowed to make every day of the Black September Organization ‘black’. The terrorists were tried and sentenced to long imprisonment terms and then handed over to the Palestinian Liberation Organization in Egypt to serve their sentences there. The US considered this to be exoneration of the murderers and reacted by nearly breaking ties with Sudan. I was assigned to Washington as Ambassador at that lowest point in our bilateral relations with the near-impossible mission to reverse the situation toward improving relations.

The success of my mission came as a result of intensive engagement with influential individuals in pivotal circles of decision-makers. On the Hill, these included Senator Charles Percy, Senator Frank Church, Senator Jacob Javits, Senator Michael Mansfield, Senator George McGovern, and many others. At the Central Intelligence Agency, CIA, I met with the Director, George H.W. Bush, later to be President. And in the State Department, I had a very positive meeting with Joseph Sisco, Undersecretary of State for Political Affairs. Finally, I had a meeting with the Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, whom I privately learned had been contacted by some of the influential personalities I had won over, foremost among them George H.W Bush. The meeting with Kissinger was the decisive factor in the success of my mission in Washington. Kissinger stated US reaction to what he saw as the release of the assassins with a hostility that bordered on being diplomatically offensive. I responded in kind, politely but assertively, by explaining the tough way Sudan had responded to the Black September assassins, with President Nimeiri vowing to make every day of their life ‘black’, which was more than any other Arab government could have done. I said that they had been tried and severely sentenced. I explained further that for internal security reasons, the terrorists had been sent to Egypt to serve their prison sentences, not released as the Secretary had alleged. I said that while the reaction of the US was understandable, the Sudanese were a proud people, and they were beginning to question why they were humiliating themselves by running after the US for friendship. As a result, even the friends of the US were being discredited and were reaching a point of despair. I concluded by stating that the US risked losing a friend who genuinely shared their values.

Secretary Kissinger surprised me by saying, “Mr. Ambassador, I agree with all that you have said, especially when you say that at this point, our policy risks becoming counter productive.” I expected a big BUT to follow. To my pleasant surprise, the BUT did not come. Instead, Kissinger turned to the Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs, William Schauffele, and his deputy, and said, “Unless you think differently, I suggest we reverse our policy on Sudan”. I had already won the support of both men, and they enthusiastically supported the change. In fact, I believe they had already convinced Kissinger who was only putting on a show of toughness to make a point. I had actually been warned by my supporters to expect a characteristic aggressive, often rude, talk from the Secretary with African ambassadors and had been advised not to react with anger. Their anticipation had played out. Kissinger then suggested that the change be made cautiously and discreetly to avoid a backlash. My next issue on the agenda was to present our proposal for a visit by President Jaafar Nimeiri which Kissinger welcomed but suggested that it be announced as ‘private’ even though it would in effect be conducted as an official visit. The meeting was successful beyond our expectations.

President Nimeiri’s visit took place and proved to be most successful. The theme of the President’s talks was to build on our domestic achievement of peace as the foundation of our foreign policy. His engagements included meeting with President Gerald Ford, the Congress, the CIA Director George H. W. Bush, and a wide range of prominent individuals in government and the private sector. In addition to Washington and New York, the delegation visited eight states. The delegations was warmly received wherever we went. The President occasionally asked me to speak for our delegation. Our case was that Sudan had ended a seven teen year war between the Arab-Islamic North and the African-Christian South through the 1972 Addis Ababa Agreement. The agreement had set the country on a course of substituting violent conflict with equitable development. Sudan was now equipped to play a major role in fostering African-Arab cooperation and contributing effectively to the promotion of regional peace and security. In a Congressional Breakfast Prayer, I was asked to introduce the President. I began by saying that it was not easy for an ambassador to introduce his President, but, recalling Nimeiri’s narrow escape from the Communist attempted coup of July 19-22, 1971 athat only failed after three days of virtual success, I said that the one thing I could say with confidence was that apart from Jesus Christ, President Nimeiri was the only one I knew who rose again from the dead after three days. The comment was met with loud laughter, and Nimeiri himself obviously relished the comparison with Jesus Christ.

President Nimeiri was widely covered in the media as a regional and international peace maker. I had worked very closely with the President and Dr. Mansour Khalid as Foreign Minister, in framing our foreign policy around these principles. In fact, I had been appointed Minister of State for Foreign Affairs and allowed to continue my mission in Washington to oversee the visit of the President before undertaking my new ministerial assignment. Wearing the two hats of Ambassador and State Minister had in fact enhanced my profile and effectiveness in Washington. I had focused my attention in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs on using our domestic achievements as pillars for our foreign policy, with a focus on our relations with key international partners, in particular the United States and the Western countries.

Sudan’s Contentious Support for Camp David Accords

The negative response to the Camp David Accords, which the senior foreign minister and the press advisor were proposing, was a clear repudiation of the core principles which the Foreign Minister, the President and I had developed and postulated for our foreign policy. “What do you think?” the President asked me after I had read the paper, passed it on to ambassador Omer Salih Eissa, and pondered over it in conspicuous silence. I told the President that I could not see how he could make such a statement. After all, he was the guest of the President of the United States of America. And the Camp David Accords were going to be among President Carter’s major achievements as President. How could he react negatively to such a major achievement of his host. “What do you suggest?” the President asked me. I told him that if asked for a position, he should say that he got the news while en route to Washington, that he had institutions for decision making at home, that he would ask the appropriate institutions to study the situation, and, on his return, would consider their reports on the basis of which he would then make his decision. Ambassador Omer supported my position. The President received our advice in silence, not showing any sign of agreement or disagreement.

Nimeiri’s meeting with President Carter the following morning was very cordial. Nimeiri spoke in Arabic, and I interpreted. When Nimeiri introduced his ministers, President Carter responded jokingly, “You have a more educated cabinet than mine. Most of your ministers are PhD holders from our universities.” I did not need to translate President Carter’s remark, as Nimeiri knew English enough to fully understand the humor, but I injected my own jocular comment by saying, “And that is the President’s problem.” People laughed. The discussions proceeded amicably. President Carter pleaded for President Nimeiri’s support for the Camp David’s Accords. At least three times, he said, “Mr. President, I need your support.” I do not recall President Nimeiri’s words in response, but he was implicitly supportive. Without saying so, he seemed to follow the advice we had given him. That became his response to the press. That visit was also very successful. The delegation returned, but President Nimeiri asked me to remain behind to follow up on some matters.

When I returned to the Sudan, I found that all our institutions, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Army, the Intelligence Agency, and the Socialist Union, all recommended standing in solidarity with the Arab rejectionist front. When I met with the President in his office, he asked whether I had seen the reports. When I answered that I had seen them, he asked further, “And what do you think?” I told him that he knew my answer. I said that our policy was based on our domestic considerations and national interests. We had ended our long war through a negotiated agreement which had been much appreciated regionally and internationally. The cordial way he had been received in the United States was a testimony to the success of our policy. How could we contradict our policy that was not only based on our domestic realities but was also serving our interests positively regionally and internationally? Besides, how had the hard-line Arab position served the interest of the Palestinians since 1948? The Arab cause had steady been losing ground and the United States mediation that resulted in the Camp David Accords was was reversing that downward trend. For all those reasons, I strongly recommended our support for the Accords.

The President asked me to write for him my own position, but to do it discreetly, indeed confidentially and not share it with anyone even in my Ministry. If I needed the research assistance of one of our diplomats, I should also do it discreetly and confidentially. That was precisely what I did with the research assistance of a young diplomat. I wrote my report in English by hand and presented it to the Minister for Presidential Affairs to be typed and translated into Arabic. After the Minister had it typed and translated, he gave me the original handwritten version and complimented me lavishly. He said the President was very happy with it. He advised me to keep the handwritten document in a safe place as it was an important historical document.

The President convened a meeting of the Politburo of the ruling Socialist Union to which he presented his proposal for Sudan’s policy on the Camp David’s Accords. From what I later learned, with minor editorial details, such as deleting the references to the way he had been personally applauded in the West for his peace policies, the statement was essentially a full adoption of my proposal. That was soon confirmed by the President’s televised statement to the Nation announcing the policy. The reactions by my colleagues in the government ranged from people who thought the policy could not have been written by anyone in the country but was probably prepared by the American CIA or the Egyptian intelligence service. The Islamist leader, Dr. Hassan al-Turabi, told me that he thought it was a good statement but too pragmatic. He did not indicate whether he thought I had a hand in it. Only one person, Abel Alier, the President of the Autonomous Southern Regional Government and Vice President of the Republic, with whom I had a longstanding relationship, told me that he saw my shadow behind the President as he read his statement. The implications of our policy on the Camp David’s Accords, which made Sudan the only Arab country to support the agreement, were far reaching in the West and in the Arab world. Our bilateral relations with the United States radically improved to the point that Sudan became third to Israel and Egypt as recipient of development and security assistance. With time, individuals began to show signs of knowing that I had a hand in shaping our Camp David policy. It was even indicated to me that I was stigmatized by rejectionists in Arab circles abroad. But that is beyond the objective of this recollection. My aim is simply to reflect on my connection to the presidency of Jimmy Carter and their effect on US-Sudan relations.

Entering the Partnership with Carter for Peace in Sudan

Most of my recollections about President Carter relate to work of the Carter Center in promoting international human rights and the efforts to end the war that had again erupted in the Sudan as a result of President Nimeiri’s paradoxical unilateral abrogation of the Addis Ababa Agreement. That was the gist of President Carter’s response to my being introduced to him when he referred to our long-standing cooperation for peace in Sudan. In a blurb to my 2010 book, Sudan at the Brink: The Dilemmas of Unity and Self-determination, he wrote, “This book is a timely reminder of Francis Deng’s lifelong efforts to advance peace and cooperation among Sudanese. It provides a strong basis for dialogue on the future of Sudan and insight on how the country’s most challenging questions can be answered.”

As former President, Jimmy Carter demonstrated that there was effective and credible leadership beyond power. Pursuing peace in the Sudan was very much on his global agenda. When I was at the Brooking’s Institution, where I was a Senior Fellow and directed the Africa Project of the Foreign Policy Studies Program, President Carter convened a meeting on the Sudan at the Carter Center, chaired by Archbishop Desmond Tutu. President Carter asked me to prepare and present the lead paper for meeting. As expected, the meeting was highly emotive. Some of the politicians were uncomfortable about the role I had been assigned and started rumors that I had lobbied for the assignment. When I heard that, I was outraged and asked to be excused from the assignment. President Carter himself intervened and persuaded me to continue with the assignment. At the meeting, he referred to the rumors and that he had personally asked me to present the leading paper for the discussions.

In my introductory statement, I recounted an interaction I had with a US diplomat with whom I had shared a ride to the Carter Center. After I answered his question about developments in the Sudan, he asked me whether I was a Southerner or a Northerner. I asked him back whether, based on what I has said he thought I was a Northerner or a Southerner. His response was that he thought I was a Muslim from the South. I told him that I was neither a Muslim, nor strictly speaking from the South, since I was from Abyei whose people, though ethnically and culturally South Sudanese, were administratively in the North. When I told this anecdote at the meeting, the late Professor Mohamed Ibrahim Khalil responded humorously that I spoke not as a Muslim from the South but as a Muslim from Iran, which made me a Muslim fundamentalist.

After the conference, while President Carter was in Nairobi, I was called by one of his aides to tell me that the President was about to have a mediation meeting with representatives of the government and the rebel Sudan People’s Liberation Movement – SPLM – and wanted to seek my advice on some issues, including information on the individuals involved. I was somewhat curious about the initiative for the mediation since I did not think that the leader of the SPLM, Dr. John Garang de Mabior, whom I knew well, was interested in mediation at that point. So, I asked the aid how the initiative for the mediation had come about. She did not know but thought that the parties had requested the President to mediate. We discussed the specific issues on which the President wanted my advice. I later learned that the mediation had not gone well, and that the President was offended that the parties sought his intervention when they were not prepared to negotiate. John Garang himself told me that he had informed the President that they were too far apart for his mediation to bear fruits. He told me that he had in fact advised the President against the initiative. Ironically, President Omer el-Bashir also told me the same thin. He said President Carter had offered to help and there was no way he could turn down such a noble thought. When I was informed by the President’s aide about what had transpired, I advised that should the President want to take such initiatives in the future, I would suggest that the Center convene a meeting with experts on the situation to give him some advice on how best to carry out his intervention.

Diverging Views with Carter on Sudan’s Conflict

Sometime later, the Carter Center informed me that they wanted to convene a meeting with Sudan experts. Could I suggest the names of persons who could attend the meeting with me at the Center. I suggested several names, and asked Professor William Zartman, a leading scholar on conflict resolution, to be a member of our team and the spokesperson. We spent the morning discussing the Sudanese civil war and agreed on recommendations to submit to the President at a concluding lunch meeting with him. At the lunch meeting, Professor Zartman presented our findings and recommendations. Central to his presentation was the regime’s imposition of the Arab-Islamic agenda in a country of diverse religions, races, and cultures. He said that imposition of the Islamic agenda was threatening the unity of the country as it justified the demand of the South for self-determination. Shortly after Zartman began his presentation, President Carter interrupted to say, and I am paraphrasing: “Wait a minute. From what you are saying, you are alleging that it is the Government that is obstructing peace in the country.” Zartman responded “Yes.” Carter resumed, “I disagree. It is the rebels who are making demands that the regime cannot accept. They are therefore the obstacle to peace. I have been to Khartoum. And I saw Christians going to Church. There is religious freedom in the country.” Alluding to the fallback goal of self-determination and potential secession of the South, he said that there was no support for self-determination that might lead to breaking up the country.

Of course, I did not agree with the President, but although I felt dumbfounded by what he said, I did not know how to express my disagreement without being disrespectful. And yet, I decided that the stakes were high and that I had to speak my mind. “Mr. President, this is a regime that has declared itself Islamic and has imposed Sharia law on the country and is openly committed to building an Islamic state. Can you say that there is religious freedom in such a country just because you saw some individuals going to Church?” As for the risk of partitioning the country, I argued that the best way of supporting the unity of the country was not to say that no one wanted the country divided, but to tell the government that the country was in danger of falling apart if conditions for unity were not created. Otherwise, the government would not feel any pressure to reform its policies. To my pleasant but uncertain surprise, the President said, “I completely agree with you.” I felt enormous relief that the President who had expressed disagreement with what Professor Zartman had reported was in full agreement with what I said. I saw the goodness in what he said, because he was offering ground for agreement. It was the drama of my confrontation with Kissinger that ended positively playing itself out again.

President Carter went on to say that he had no vested interest in whether the country was united or partitioned. I saw all this as a mix of a personal point of view and a sincere desire to explore a common ground. It also revealed that the President was more driven by the lofty vision of peace and did not want to be distracted or constrained by contradictory details. Our differences did not in any way impact negatively on my highest regard for the goodness of his motivations. And as he said when I was being introduced to him, we continued to work closely together in the search for peace in Sudan.

In seeing the rebel movement as the obstacle to peace, President Carter was alluding to the movement’s vision of New Sudan of inclusivity and equality that would transform the system in a way that threatened the establishment and therefore unacceptable to the system. I recall a discussion at a dinner hosted by the Zartmans that was attended by the US Ambassador to Sudan. The ambassador’s argument was that John Garang was too hard a negotiator and was making demands that the government in Khartoum could not sell to the people. I found the argument disingenuous as Garang was the aggrieved and calling for justice. But I was almost amused when Garang later intimated to me the tactic he used in negotiating with Vice President Ali Osman Mohamed Taha. He said he would raise the bar step by step and persuade Ali to concede each step until he reached a point from which he could not descend. Ali Osman would incrementally thereby commit himself to more than he had planned but could no longer retreat. He was essentially corroborating what the ambassador had told me, but which I had vigorously refuted.

In our discussion with President Carter, after revealing what appeared to be some empathy for the Sudan government’s pursuing an Islamic agenda, he made an off-the-cuff, presumably jocular remark, “If I could make the United States a Christian country, I would.” The President was presumably alluding to the tension between his subjective aspirations for the role of religious values in public life and the well-established principle of separation between religion and state, especially in religiously pluralistic societies. President Carter has been described as ‘a progressive White Evangelical Christian’ who believed in the values of Christianity but strongly opposed White racism and discrimination as unchristian. That was what took him close to Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Rev. Andrew Young and other civil rights leaders.

Evangelicalism and the Role of Religion in Public Policy

I witnessed the progressive Evangelical Christianity in the activities of the Christian Fellowship which, at the time I was ambassador in Washington, was championed by Doug Coe, an Evangelical leader of a Christian organization primarily known for hosting the annual National Prayer Breakfast. Doug was very influential in the Christian Fellowship Movement and built a wide network of powerful political leaders in different parts of the world. He was able to gain access to presidents and other influential leaders worldwide without drawing public attention.

Doug was a very pleasant, smiley, and gentle operator. Discreetly active in Washington diplomatic circles, he approached me shortly after I arrived in Washington as Sudan’s Ambassador to recruit me into his Fellowship. I shared with Doug my religious skepticism, the result of my comparative religious experiences starting with my background in traditional African spiritual tradition through educational transition in schools that were dominated by other religions, including Christianity (both Catholicism and Protestantism) and Islam. Surprisingly, the more he learned about my skepticism, the more he seemed to believe that I was the right person to target. He said he did not believe in the dogmas of formal church but in Christ whom he said represented universal values. He was persistent enough to win me over. He in fact became one of the main supporters of my mission in Washington. He helped facilitate the Congressional Prayer Breakfast for President Nimeiri. And he later hosted one of Garang’s visits to Washington by accommodating him and his delegation their Fellowship Guest House and organized Prayer Breakfast for him and his delegation. The Fellowship has since evolved into a powerful political constituency in Washington, thereby intensifying the tension between separation of religion and state and the linkage of the religious agenda with politics and public policy.

I do not know what role religion played in President Carter’s global mission for peace, but his dedication to the search for peace in Sudan was deeply spiritual and relentless. In 1993, when Congressional leaders were trying to reconcile Dr. John Garang de Mabior with his rival comrade in the liberation struggle, Dr. Riek Machar Teny, and the two were invited to Washington for that purpose, President Carter tried to intervene to help the mediation process. He therefore invited both men to Atlanta for mediation talks. Riek Machar accepted the invitation, but President Carter got no response from John Garang. So, he called me to intercede with John Garang. Unfortunately, Garang presented me with a dilemma. He definitely did not want to go to Atlanta for the mediation talks with Riek Machar. He did not see what those talks could achieve that the Congressional mediation could not do. Besides, he recalled the previous experience with the President when he said he had advised him against interceding between them and the regime in Khartoum as they were far apart. He said the President had decided to proceed with his efforts, but was then offended when he could not reconcile the differences between the parties. Garang did not want to repeat that experience. But what should I tell the President? Of course, I could not tell him what Garang had said to me. And yet, I could not misrepresent the situation. I procrastinated. And the issue faded away seamlessly.

Although Washington had long ceased to accuse the SPLM of communist leaning and the Movement had in fact become popular, the country was divided on US policy on Sudan. There were those who saw the demands of the SPLM for a New Sudan too idealistic and unattainable. And there were those who sympathized with the cause of the South for secession. My impression was that President Carter was poised in the middle. He wanted the war to end within a framework of unity, but he also appreciated the cause of the South. This became clear to me in a conversation I had with him. I reported to him a discussion I had with John Garang. I told Garang that I of course shared his New Sudan Vision, but I asked him whether that should be pursued at all costs, even at the risk of our people getting exterminated in the process, or should we accept a compromise solution to save our people and strengthen their capacity to pursue the New Sudan Vision politically over time? Garang’s response was “What you are asking me is to compromise even if it means that our people remain second class citizens. And why would people allow themselves to be exterminated any way?” I argued that people do not allow themselves to be exterminated; they get exterminated against their resistance. Garang was of course not persuaded. When I told President Carter my discussion with John Garang, his reaction was, “I understand what he means.”

CSIS Task Force on US Sudan Policy

It was to develop a cohesive and unified US policy on Sudan that in July 2000 the Center for Strategic and International Studies, CSIS, set up a Task Force on US Policy to end Sudan’s War to be submitted for the consideration of the incoming administration of George Bush or Al Gore, whichever of them would win the Presidential elections. I was honored to co-chair with Stephen Morrison, a diplomat who headed the African Program at CSIS. Our friends in Washington were opposed to the Task Force because they suspected Steve Morrison as being pro-Khartoum. They advised me against accepting the co-chairmanship and even warned Garang against the risks involved in the mandate of the Task Force. The United States Institute of Peace which provided the funding for the Task Force wanted me to co-chair it. I also felt that if I did not do that, someone else would do it and there was no telling whether that would be in our interest. Although our friends succeeded in persuading John Garang to be suspicious of the Task Force, he approved of my participation for damage control. At the beginning, I had some Sudanese in Washington from both North and South invited to attend the meetings of the Task Force. But the confrontation between them soon proved disruptive to the work of the Task Force, and they were therefore excluded from the meetings. That left me as the only Sudanese on the Task Force.

In its report on the Task Force, CSIS wrote: “The CSIS Task Force on U.S.-Sudan Policy, funded through a grant from the U.S. Institute of Peace, was launched in July 2000 with the aim of revitalizing debate on Sudan and generating pragmatic recommendations for the new administration. Cochaired by Francis M. Deng, then senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, now distinguished professor at the City University of New York Graduate Center, and J. Stephen Morrison, director of the CSIS Africa Program, the task force at all points operated on a nonpartisan, inclusionary basis. It relied on the active participation of more than 50 individuals and presentations by several experts on select topics. Regular participants included congressional staff, human rights advocates, experts on religious rights, academic authorities on Sudan, former senior policymakers, refugee advocates, representatives of relief and development groups, and officials of the Clinton administration and United Nations, among others.”

The work of the Task Force proved to be very challenging. The overwhelming majority argued that the United States had no strategic interests in Sudan. The only concerns of the United States were Sudan’s involvement in international terrorism, its destabilization of neighboring friendly countries and the humanitarian tragedy caused by the civil war between the North and the South. The General view was that if George Bush won the elections, his focus would be internal and less on foreign policy. They argued that the peace process should be left to Europe, and the US should only assist in the background. They were also against self-determination by the South that would risk partitioning the country.

Of course, I did not agree with that position. Though careful not to abuse my position as co-chair, I argued that Sudan, located as it is at the intersection of North Africa and sub-Saharan Africa, was at a strategic meeting point of civilizations, races, cultures, and religions. It could be a point of peaceful and conciliatory interaction or of confrontation and violent conflict with repercussions extending into the Middle East. Sudan was also rich with vast natural resources, including plentiful arable land, livestock, and minerals. The United States as the sole super power could not afford to be indifferent to a country of such strategic importance.

I argued that we should reverse the order of the policy considerations specified to prioritize ending the war. Sudan’s involvement in international terrorism was in reaction to support they believed South Sudan was receiving from the Christian West. They therefore identified with the Middle Eastern anti-West terrorists on the ground that the enemy of my enemy is my friend. Destabilizing the neighboring Black African countries was also in reaction to the support these countries were understood to be giving South Sudan. And of course, humanitarian tragedy was the result of the war. End the war and Sudan’s involvement in terrorism would end, destabilizing the neighborhood would also end, and humanitarian tragedy would be mitigated. As for the objection to self-determination, as I had said to President Carter, the best way to ensure the unity of the country was not to deny the right of self-determination to the South, but rather to challenge the government that unless they created conditions for unity, the country was threatened with patrician. Self-determination did not need to be viewed as a predetermined path to Southern secession, but as a pressure to make unity attractive to the South. I therefore supported self-determination not because I wanted the South to secede, but in order to help create conditions for consensual unity.

I concluded that since unity was the shared vision for the country, the challenge for the Task Force was to make possible the impossible and reconcile the irreconcilable. If the North insisted on the Arab-Islamic agenda, then let that be. And if the South wanted to build their governance system on their African culture and value system, let that be too. The two should then create a framework of unity in diversity. The trend of the discussion gradually shifted in that direction and The Task Force ended on recommending a framework of ‘One Country, Two Systems.’ The Task Force also recommended that the US should play a leading role in the peace process.

The Pivotal Initiative of the US in Ending Sudan’s War

When George W. Bush won the 2000 presidential elections, contrary to the prediction of the Task Force that he was domestically focused and not interested in foreign affairs, he became actively engaged in international issues, including involvement in the Sudan peace process. Christian Right constituency was particularly active in advocating the cause of Southern Sudan. President Carter was a neutral peacemaker who obviously pursued that mission after his term in office. He recruited President George W. Bush to join him in that call. In his remarks at the dedication of President George W. Bush Library on April 25, 201, President Carter recalled the way he got President Bush involved in the Sudan peace process. “My wife and I were the only two volunteer Democrats on the platform. George and Laura afterwards came up and thanked us for coming, and so he said “Now, if there’s anything I can ever do for you, let me know.” Which was a mistake he made. I said, “Mr. President, the Carter Center has programs in 35 countries in the world, and the worst problem now is a war going on between North and South Sudan, and millions of people are being killed. And I’d like for you to help us have a peace agreement there.” And in a weak moment, he said, “I’ll do it.” And I said, “when can I meet your Secretary of State and your National Security Advisor?” He said, “Well, I haven’t even chosen them, yet. But give us three weeks.” So three weeks later I came up and met with Colin Powell and Condoleezza Rice and President Bush kept his promise. He appointed our distinguished senator from Missouri, John Danforth and a great general from Kenya named Sumbeiywo. And in January of 2005, there was a peace treaty between North and South Sudan. that ended a war that had been going for 21 years. George W. Bush is responsible for that.”

What to Remember President Carter For

It would of course be presumptuous of me to pay tribute to President Carter’s accomplishments in areas which are well known globally. Enough to note that he was a Nobel Peace Laureate. His stance agains racial discrimination and support for advancing civil rights in the United States is widely acknowledged. Jimmy Carter also worked to combat world hunger and poverty. His success in the eradication of deadly diseases, specifically Guinea worm and river blindness, which afflicted large numbers of school children in South Sudan, is a spectacular accomplishment. His Habitat for Humanity programs in which he built homes for the poor, contributing his own physical labor to the construction, is another towering legacy. And there is also his unflinching commitment to the politically sensitive promotion of human rights protection worldwide. While in office and as former President, Carter did so much more than I can even attempt to cover comprehensively in this modest tribute. It is what I call leadership beyond power.

Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter acting as referendum observers in South Sudan.

The experience of Sudan shows that promoting peace, unity and reconciliation is a complex process in which roles undertaken by different individuals and entities are complementary and mutually reinforcing. The pivotal role the United States eventually played in mediating an end to the war was a commutative outcome in which regional and international organizations and think tanks played roles at various stages, with varying emphases on the issues involved. While a few individuals and organizations featured prominently as the decisive peacemakers, and most remain incognito, it is fair to acknowledge the outcome as a collaborative shared achievement that should be gratifying to all concerned. President Carter was certainly a tower pillar in this collaborative peace architecture. For me personally, it was most touching that President Carter referred to our working together for peace in the Sudan in the flattering way in which he responded to my being introduced to him.

In that sense, President Carter’s efforts and achievements in the search for peace in Sudan and elsewhere in the world are those of a leader among countless collaborators and partners of varied profiles and positions. He will be missed but remembered by a wide range of people across the globe. As I have often said, immortality, holistically perceived, is a combination of the life hereafter conceptualized by the Christians and Muslims as Heaven, and the continued identity and influence of the departed in this world through the memory of the living, which is the core of the indigenous African belief systems. On both grounds, the continued identity and influence of President Carter and his lifelong Partner-Spouse, Rosalynn, in both worlds are undoubtedly assured.

So, what is the value of my paying tribute to this towering world leader? The answer is to share a personal, albeit modest, human dimension of his impact on me and through that experience shed some light on his portrait as a global leader who related to all people deferentially and with unprecedented display of decency, humanity, humility, and dignity. I hope that in my modest way, I have done some justice to a man whose immortal profile is far beyond my words.

May the Almighty God rest the souls of Jimmy Carter and his beloved lifelong Partner-Spouse, Rosalynn Carter, in everlasting peace which they together, so vehemently pursued for humanity in this world.