Tracing the Çapulcu: Historical, Ethnographic, and Global Perspectives on Mass Politics in Turkey Today

Blurry photographs of tear gas and swinging bobby clubs, headlines announcing unprecedented police violence and political strife: for most consumers of the international news media, the demonstrations surrounding Gezi Park (Gezi Parkı), in Istanbul’s central Taksim Square, which began in late May and continue sporadically in spite of state and police repression, amount to little more than these images and words, indistinguishable from countless other contexts around the globe. As historians well know, such images and words may constitute the fodder, the raw material of historical narratives, but they do not provide these narratives in and of themselves. Unfortunately, this crucial distinction between images and narratives regularly eludes the mass media, with its double imperative of sensationalism and immediacy. Such has been the fate of the Gezi Park demonstrations among international commentators and interpreters. Even when reportage on the protests does offer an explanatory narrative, it tends to reduce the intricate, multifaceted context to the simplistic binary of “secularists” vs. “Islamists” (e.g. https://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/14/opinion/global/turkeys-growing-pains.html?_r=0); I have already criticized this dubious, if intractable, dichotomy and the manner in which it frames Turkish politics here: (https://blogs.ssrc.org/tif/2013/06/10/an-excursion-through-the-partitions-of-taksim-square/). In this brief essay, I aim to expand and complicate the field of interpretation of this summer’s protests in Istanbul along three dimensions: the historical, the ethnographic, and the global.

Two key aspects of the demonstrations—their initial focus on Gezi Park, a small stand of sycamores and crabgrass adjacent to Taksim Square, and their rapid diversification, which weaved together a whole host of causes and complaints—only make sense in the context of a broader political history of public space in Istanbul. Since the dawn of the modern Turkish Republic in 1923, Taksim Square has been the privileged locus and epicenter of mass politics and protest in Turkey. In 1928, only five years following the dismantling of the Ottoman Empire, the Republic Monument (Cumhuriyeti Anıtı), a massive statue depicting Mustafa Kemal Atatürk—war hero and revered father of the Turkish nation-state—was erected at the center of Taksim Square, thus proclaiming the hegemony of the Turkish state project and saturating Istanbul’s preeminent public space with this project (Image 1). In 1977, against the backdrop of escalating street violence between leftist and rightwing nationalist groups—the eventual, partial cause of the 12 September 1980 military coup—Taksim was the site of a notorious instance of state violence against civilian protestors. A broad coalition of unions and leftist organizations gathered in the square to commemorate May Day (known in Turkish as “The Worker’s Holiday, İşçi Bayramı). When state security forces began to clear the square, general panic ensued among the 500,000-odd demonstrators, resulting in the deaths of at least thirty-four. Beginning in 1979, May Day demonstrations were prohibited in Taksim Square; while the ban was lifted temporarily in 2010, it was reinstated this year, ostensibly due to the very redevelopment project that ignited the current protests.

More recently, Taksim Square has become an object of desire for members of Turkey’s new political establishment, the Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi; AKP). Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, whose increasingly draconian political demeanor is a central complaint of the Gezi protestors, first proposed the construction of a massive mosque on the square during his stint as Istanbul’s mayor in the mid-1990s; plans for the mosque continue to resurface every several years, and have even resulted in a widely-praised proposal by a prominent Turkish architect, Ahmet Vefik Alp (https://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/24/world/europe/mosque-dream-seen-at-heart-of-turkey-protests.html?pagewanted=all). Reportedly, Erdoğan rejected this proposal as “too modern”—he would prefer a design in the Ottoman architectural tradition. Unsurprisingly, an array of secular political and civil society groups have adamantly opposed the mosque plan—from their perspective, a monumental, government-sponsored mosque would violate the secularist character of the square. The aforementioned statue of Atatürk is the principle custodian and guarantor of this secularity of Taksim’s public space, but it is also embodied by state institutions such as the Atatürk Cultural Center (Atatürk Kültür Merkezi, AKM), which Erdoğan has threatened to dismantle as part of the current redevelopment of the square (https://www.radikal.com.tr/politika/erdogan_akm_yikilacak_taksime_cami_de_yapilacak-1135947).

Clearly, the dominant narrative of a zero-sum competition between Turkey’s secularists and Islamists is an unavoidable aspect of the politics of public space in Taksim Square; it is unsurprising that international media have by and large favored this narrative. My point here, however, is different. Taksim has served as the proscenium of Turkish mass politics throughout the history of the Turkish Republic; that it continues to do so today, on an international stage, is no coincidence. At certain moments and conjunctures—notably May Day 1977—demonstrations in Taksim have been entirely indifferent to the narrative of Islamism and secularism. More generally, the puissance and resonance of Taksim as a site of and for mass politics exceeds and defies regimentations of specific interests, causes, and political narratives, including the narrative of Islamism and secularism. Even a casual ethnographic portrait of the Gezi Park demonstrations vividly evinces the excessive heterogeneity that characterizes both mass politics in general and the politics of protest in Taksim specifically.

Regrettably, I was not in Istanbul when the demonstrations began in late May. When I arrived on June 24th, in Turkey on a forty-eight hour layover, I immediately made my way to Taksim. The scene was curious, reminiscent of the afterhours following a raucous party that the participants have yet to reconstruct fully in memory. Gezi Park itself was entirely closed—the police had emptied it on June 15th, and maintained a cordon to prevent any ambitious demonstrators from reoccupying it. Official signs printed in the familiar font and characteristic bureaucratese of the city government proclaimed, with mute irony: “Gezi Park is being renewed by the Directorate of Parks and Gardens (European Side) of the Greater Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality.” (Image 2) In the square proper, just to the south of the park, a handful of protestors silently faced the aforementioned Atatürk Cultural Center, which was draped in a giant banner of Atatürk himself, limned by two equally-massive Turkish flags (Image 3). The protestors mimicked the pose of the “standing man” (duran adam), Erdem Gündüz, who reinvigorated the demonstrations with his silent vigil on June 18th (https://www.huffingtonpost.com/christopher-burgess/duran-adam-standing-man_b_3475014.html). Near the front of the small group of silent demonstrators, two young men held a sign announcing a march planned for the following evening, to protest the release of Ahmet Şahbaz, the policeman who fatally shot a protestor, Ethem Sarısülük, in Ankara on June 1st. Several young children milled through the crowd selling bottled water; purveyors of tea, Nescafe, and simit, the distinctive, sesame-encrusted Turkish bagel, plied their wares on the margins of the square.

The solemnity of the scene on Taksim Square that I witnessed in late June contrasts sharply with the carnivalesque atmosphere that pervaded Gezi Park prior to its police-enforced evacuation. In conversation, friends who had spent time in Gezi regaled me with their effusive enthusiasm. As one of my acquaintances put it in an email prior to the park’s evacuation, “While walking through Gezi Park I feel better than I have in my entire life…it’s as if a free environment has come into being, one in which everyone can express themselves, in which nobody judges one another, in which no pressure is applied…(here) we are all in solidarity with one another (buralarda dolaşırken kendimi hayatım boyunca hissetmediğim kadar iyi hissediyorum, kimsenin birbirini yargılamadığı, baskı uygulamadığı, kendilerini ifade edebildikleri özgür bir ortam oluştu adeta, herkes dayanışma içinde).” Most importantly, any attempt to reduce this unique sociality of solidarity to a single political aim or social demographic would be both futile and cynical. Although most of the Gezi Park demonstrators expressed intense dissatisfaction with the person of Prime Minister Erdoğan and the decade of neoliberal AKP governance in Turkey generally, they were not a simple agglomeration of “secularists” aligned against the “Islamists”. As Ateş Altınordu observes in a refreshing, unique essay on the demonstrations (https://blogs.ssrc.org/tif/2013/06/10/occupy-gezi-beyond-the-religious-secular-cleavage/), one of the most active, visible institutional occupants of Gezi Park were the “Anti-Capitalist Muslims” (Antikapitalist Müslümanlar: https://www.antikapitalistmuslumanlar.org), hardly a “secularist” body. More generally, the heterogeneity of the participants in the demonstrations—LGBT groups, unions, environmentalists, leftists and anarchists of every stripe, Sufi-inspired mystics and yogis, as well as self-identified secularists—constituted a watershed moment in Turkish mass politics, one no longer defined by singular issues and identities. Perhaps the best testament to the distinctiveness of Gezi—its novel political sociality, the “free environment of expression and solidarity,” irreducible to a single cause or aim—is the fact that a large number of participants espoused no particular “identity” or “interest” at all. No less prominent a political theorist than Slavoj Žižek emphasizes this very “aimlessness” in a fine essay comparing the Turkish protests with the ongoing demonstrations in Greece:

It is also important to recognize that the protesters aren’t pursuing any identifiable ‘real’ goal. The protests are not ‘really’ against global capitalism, ‘really’ against religious fundamentalism, ‘really’ for civil freedoms and democracy, or ‘really’ about any one thing in particular. What the majority of those who have participated in the protests are aware of is a fluid feeling of unease and discontent that sustains and unites various specific demands. (https://www.lrb.co.uk/v35/n14/slavoj-zizek/trouble-in-paradise)

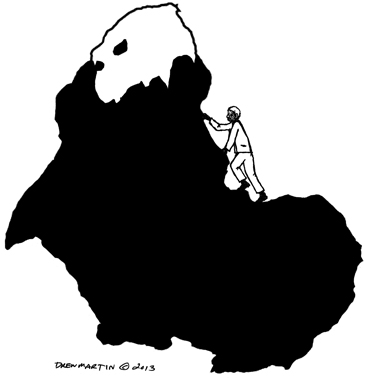

In his own way, Prime Minister Erdoğan has also gestured to the definitive heterogeneity of the Gezi demonstrators. During a speech on June 2nd, he drew on a rather obscure Turkish term, “çapulcu” (roughly translatable as “looter”) to describe the protestors as a whole (https://haber.sol.org.tr/devlet-ve-siyaset/erdogan-onbinleri-birkac-capulcu-ilan-etti-diktatorluk-kanimda-yok-dedi-haberi-739). Rather unsurprisingly, the protestors seized gleefully on the label themselves, coining the neologism “chapulling” in the process—a Youtube video titled “Everyday I’m Chapulling” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j5s0yuPPw9Q) concisely captures the festive, mischievous contrarianism of the “çapulcu.” Indeed, if a single “identity” can be said to encompass the demonstrators, it is surely that of the çapulcu, a new figure on the Turkish scene who has yet to take up a single banner or cause.

From the vantage of this ethnographic portrait of the Gezi demonstrations, with its emphasis squarely on the carnivalesque, expressive heterogeneity of the protests, we can now briefly direct our gaze to their global dimension. An immediate response of many commentators was to compare and contrast Taksim Square with the two major urban mass political movements of the past several years, the Arab Spring and the Occupy Movement (e.g. https://arcade.stanford.edu/turkey-occupy-not-spring). Other, fruitful comparisons could no doubt be drawn with a myriad of other contexts, including the ongoing protests of the “Salad Movement” in Brazil, student protests in a variety of countries, including Croatia (2009) and Chile (2011-2013), and anti-austerity demonstrations across Europe. More important, perhaps, is the manner in which the Gezi protests articulate with the shifting forms and powers of global capitalism—as Žižek underscores in his essay, protests such as those in Turkey and Greece demonstrate the gradual decoupling of liberal democracy and neoliberal capital. In closure, however, I want to pause on the novel, heterogeneous, carnivalesque sociality that was so vivid and visible in Gezi Park, embodied especially in the figure of the çapulcu. This festive sociality, which is deeply political without being instrumental, or even easily instrumentalizable, has clear analogues in other contexts of mass politics and protest throughout the globe. We have seen çapulcus reveling in Zuccotti Park, holding vigil in Tahrir Square, and swarming around Oscar Niemeyer’s Congresso Nacional in Brasilia. Ultimately, one lasting contribution of the Gezi Park demonstrations may be to lend a coherent title to this carnivalesque figure of contemporary mass politics on a global scale. Time will tell. Until then, well, “everyday I’m chapulling…”

*The author thanks Karin Doolan for her invaluable comments and guidance.

Jeremy Walton is Postdoctoral Fellow for the Study of Secularism and New Religiosities, CETREN Project, Georg August University of Gottingen.