Something in the Air: Assayas’ Portrait of Political and Personal Upheaval Post May ‘68 France

In May 1968 France was roiling with mass demonstrations, student occupations, strikes, and riots. Initiated by a student revolt–more social and cultural (against convention and authority) than political–the students were then joined by workers in an assault on France’s most venerable institutions. Occurring during a time of relative economic prosperity, this upheaval turned into the first ever nation-wide wildcat general strike by workers (breaking from the traditional trade union–often Communist–leadership). At the height of its fervor, the turbulence virtually brought the entire French economy to a halt. The strike involved 11 million workers, and went on for two weeks, almost causing the collapse of French President Charles De Gaulle’s paternalistic and conservative government.

It was the workers’ strike that was most threatening to the government, not the student movement–and they generally followed separate paths. The students’ demands and perspective were more diffuse–often sexual, and philosophical in nature (e.g., “The liberation of humanity is all or nothing or “Boredom is counterrevolutionary.”) However, among the students there were left sectarians –Maoists who were more rigidly ideological. The workers’ demands were more precise. And when the government responded by offering pay rises and reduced working hours, a 35 per cent increase in the minimum wage, a shorter working week and mandatory employer consultations with workers, the strike came to an end, and the movement petered out.

The protests of ‘68 may not have lasted long, but in no other country did a student rebellion help to almost bring down a government, nor had one ever led to a workers’ revolt. I know the American student movement never came remotely close to having that large an impact, and blue collar workers in this country were often fiercely antipathetic to both the student movement’s counterculture and Left elements.

A number of French films have dealt directly with or touched on May ‘68. They include: Godard’s epigrammatic, irritating, and fractured narrative La Chinoise (1968); Louis Malle’s satiric May Fools (1990); Bernardo Bertolucci’s erotic, sensual, and nostalgic The Dreamers (20003); and Phillipe Garrel’s dour, tedious, and exquisite Regular Lovers (2005). One must also add Olivier Asaayas’ (e.g., Summer Hours, Carlos) semi-autobiographical Something in the Air (or Après Mai, the French title)—though it takes place a few years later in 1971. The film’s thin, pale, sensitive, long haired 17 year-old protagonist, Gilles (Clément Métayer)– acted by a non-professional like almost all its young actors -–is Assayas’ alter-ego. He is in his last year at a suburban Paris lycée, where Marx and Pascal are taught and discussed, and he is on his way to art school.

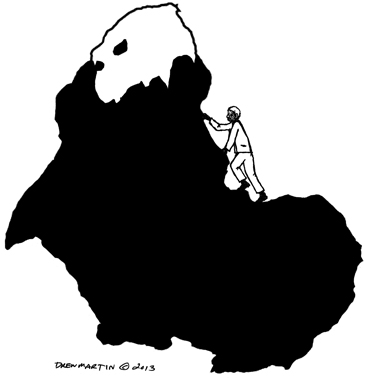

Gilles, who sees himself as an anarchist (Assayas was intellectually influenced by the Situationists who combined a passion for experimental art with anti-authoritarian left politics) is involved with the radical high school movement–handing out leaflets and broadsheets, spray-painting graffiti slogans on the walls of school buildings, and engaging in violent confrontations with school security guards, and with the brutal baton-wielding Parisian riot police. Assayas depicts the conflict with the police with visceral immediacy, and the protestors, though banged around and arrested, take pleasure in proving themselves through combat. He also seamlessly captures the ambience of those earnest political meetings where political tactics and ideology were articulately and endlessly debated. The students here engage in a strenuous attempt to define a political line, and a range of factions– Trotskyists, Maoists, Anarchists– all take part in ideological dispute, with the exception of the Communists, who feel the tactics of these young radicals discredit the Left.

But the joy, wit and utopian impulse that was part of May ‘68 no longer exists for these young radicals. They are ideologically solemn, rhetorical, and at times gratuitously destructive. They know the political moment has passed, but they continue the struggle–possibly as much out of nostalgia for ‘68 than out of conviction. And Assayas’ portrayal of them is sympathetic, though never sentimental. In some ways he’s critical, conveying a clear-eyed but never explicitly judgmental view of their adolescent pretensions and moral callousness. (e.g., Engaging in an act of violence they send a security guard to a hospital with a coma, exhibiting not an iota of guilt for what they have done.)

Gilles’ political commitments turn out to be secondary to his desire to become an artist. In Assayas’ words: “The center of the movie is really the evolution of the history of the relationship to art. It starts from Gilles’ painting and drawing abstraction to accepting he will one day become a filmmaker, and that cinema in a certain way can be considered as a superior form of representation. It’s really the undercurrent of the film.”

Still, Gilles, while pursuing his artistic ambitions (trying to find a medium and style) in a disciplined not dilettantish fashion, remains political, though he begins to convey a touch of skepticism about adhering to a hard political line. He reads Orwell, and a book critical of Mao, and travels to Italy for the summer with a film collective that makes agit-prop films for workers, who they romanticize. Gilles quietly questions the philistinism and conventionality of their films’ syntax, implicitly affirming the 1970 Godard (One Plus One) who believed revolutionary films demand an experimental, revolutionary style and who therefore rejected social realism. In Godard’s words, “The problem is not to make political films, but to make films politically.” I remember the intensity of the aesthetic conflicts between political filmmakers and critics who espoused an experimental style, and those who wanted art to be populist and accessible. Assayas succinctly captures the nature of that debate, as he does so much else of the period’s atmosphere.

He does this, however, by eschewing the construction of a tight narrative, and doesn’t bother filling in all the details. He leaps from episode to episode, leaving many unanswered questions about the characters’ behavior. His aim is to create an impressionistic portrait of a period of personal and political upheaval as seen through his younger self. Consequently, we get a powerful feeling of the era’s radical turbulence without any real analysis of the ideological differences on the Left, or of the movement’s failures.

One episode is a summer vacation trip to Italy with two radical high school friends, a fellow committed artist Alain (Félix Armand), and sweet, low-keyed Christine (Lola Créton), who he becomes involved with. They drift from place to place working at their drawing, and hanging out with a group of too beatific-looking hippies singing political folk songs. Christine is more unwaveringly political than the two boys, and leaves them to join an older filmmaking collective–where she is unhappily relegated to shopping, cooking, and doing pedestrian work, and cut off from decision-making. (Assayas in passing commenting on her playing a subordinate role, echoes the fate of many women on the left in that period.)

Among the hippies is a red-haired American diplomat’s daughter Leslie (India Salvor Menuez), a student of modern and sacred dance. She and Armand develop into a couple, but their inexpressive interaction never comes alive, and their scenes together undermine the film’s momentum.

In fact, Assayas centers the film on Gilles’ coming of age, and except for his first love, Laure (Carole Combes)–a striking-looking, mysterious, aesthetic, depressed young woman– who Assayas sees as embodying “the spirit of poetry” (a perfect hard-to- fully-get-hold- of fantasy woman for an artistic adolescent like Gilles), none of other characters are given much dimension. One friend, Jean-Pierre (Hugo Conzelmann) is an unsmiling full time revolutionary, diligently mimeographing leaflets and writing for Left papers, who views Gilles as a political outsider, choosing artistic solitude rather than radical action. But he makes little impact on the film. Nor does Gilles’ father, a television scriptwriter forced by Parkinson’s disease to employ his recalcitrant son in adapting Simenon’s Maigret for French TV. Gilles ultimately takes the work, but condemns his father for being a hypocritical hack, and then shows how smart he is by smugly criticizing the structure of Simenon’s work.

The film is filtered through Gilles’ egocentric personality (e.g., he displays no sympathy for his father’s illness), so every place and person is seen through his eyes. It’s not only his friends who remain ciphers, but also we learn nothing about the nature of the suburb he grew up in. Also, as he drifts away from politics, he is pushed by Jean-Pierre to demonstrate that he’s still an anarchist by blowing up a car. It’s a symbolic but nonsensical act that feels just dropped into the film.

The strength of Something in the Air lies in its perceptively conveying the feeling of adolescents (albeit mostly privileged, financially comfortable ones) seeking to define themselves, by taking on new roles and identities. The film’s fragmentary, drifty style perfectly suits the collective psyche of Gilles and his friends. It’s both a heady and difficult time for them. They are adolescents free to make choices, travel about the world, and have a great deal of unself-conscious, pleasurable sex. And a number of them, including Gilles, seem to drop their political activism without much reflection or guilt, though without turning to the right.

At the film’s conclusion, Gilles is working in London as a gofer on a ridiculous science fiction movie complete with papier-mache monsters and a Nazi U-boat. He has stopped searching and found his calling, but this is just the first fledgling step on the path to making the kind of films he ultimately wants to direct. Those are the films he goes to see at the avant-garde Electric Cinema in Notting Hill, where while he is sitting in the theater the image of Laure is suddenly resurrected on the screen—strikingly embodying the artistic life that Gilles will follow.

Something in the Air does not delve deeply into Gilles’ internal life. But without being formally virtuosic or in any way experimental, Assayas utilizes the underground music of the period, and stirring images of chaotic parties and street battles which leave an indelible portrait of a time, and of a sophisticated adolescent’s coming of age. Though the politics of many of the adolescents may be rigid or ephemeral, Assayas is a director with a keen political intelligence, and critical commitment to the Left. This is a film that has never received the attention it deserves.

Leonard Quart

.