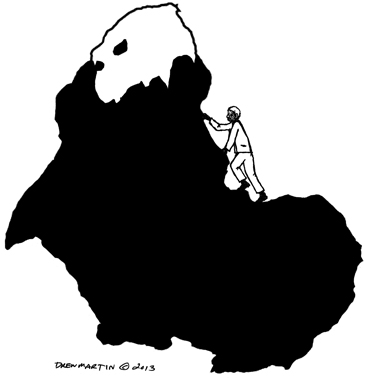

John Nichols, On Top of Spoon Mountain

John T. Nichols (not to be confused with The Nation columnist), age 73, is a novelist, non- fiction author and screen writer who moved to Taos, New Mexico from the East Coast following the success of the 1969 film version of his best selling novel, The Sterile Cuckoo. Nichols fell in love with his adopted home, and applied to northern New Mexico his exceptional skills as a writer and environmental-political activist while hiking the region’s peaks and gorges with fishing pole, hunting rifle and camera. His “New Mexico trilogy” includes the novel The Milagro Beanfield War, which in 1974 was adapted into a famous movie by Robert Redford. He is the subject of a 2012 documentary The Milagro Man: The Irrepressible Multicultural Life and Literary Times of John Nichols.

On his own rather whimsical web site, Nichols states, “I’ve been married and divorced three times, helped raise two kids, and survived open-heart surgery in 1994.” He also comments on his own puzzlement about “where all the money went” and on the currently precarious state of his health: “my heart is locked in permanent atrial fibrillation, I’m in congestive heart failure, I take Lanoxin and Carvedilol and aspirin every day, and my doctor says I’m a walking time bomb ready to have a stroke. So it goes.”

Nichols’s unflagging good humor and deep concern for our collapsing environment show through in this bemused autobiographical sketch, just as in his latest novel, On Top of Spoon Mountain, whose main character and narrator is an aging Taos-based author named Jonathan Kepler, who wonders early in the novel, “There is a new sense of foreboding in my life that makes me anxious. Hungry wolves are gathering on the edge of my perimeter. Have I segued into my own end game?”

Jonathan Kepler is a 64 year old, unrepentantly-radical sometime mountain-climber (“I ate Spoon Mountain for breakfast.”) and formerly-famous novelist and screen writer who hasn’t had a best seller or a hit movie in many years now. Jonathan lives in semi-obscurity and declining health in a New Mexico mountain town where the forests are burning up, the rivers are drying up and both the planet’s and his own future prospects seem dim, and where he might understandably have surrendered to isolation, cynicism and despair. Jonathan is even bogged down in a frustrating effort to complete an unwieldy final book which he calls “my Magnum Opus”: ”The Magnum Opus is a novel, a massive, and, I would like to think, clever satire about pending Armageddon. . . . At nearly a thousand pages so far, the manuscript of my Magnum Opus is daunting. There are over fifty characters. I like to think big (hence I usually fail big). . . . Although the entire project is a muddle I am not discouraged—yet I need to wrap it up, don’t I? . . . Time is of the essence. And these days I hear Time’s winged chariot drawing near. . . . I don’t know what is wrong with my shit detector.”

Still, despite a long series of disastrous marriages and liaisons, Jonathan clings to love, or to the hope of love. He does have a still-beloved movie adaptation of one of his most loved novels, The Lucky Underdogs (which closely resembles that famed New Mexico book-movie pairing Milagro Beanfield War) under his belt, and he has a little grand daughter whom he deeply loves and who loves to play with him.

For those reasons, Jonathan still clings to a cock-eyed optimism, despite all evidence to the contrary, that his life might turn out alright in the end. Just as the aging T.S. Eliot, despite being the 20th century’s prime poet of rational despair, found comfort in late-life love and the company of cats, Jonathan clings to what works for him. Jonathan and his grand daughter conduct raucous private conversations in the squawking lingo they’ve learned from the ravens observed munching garbage behind a popular Taos, New Mexico bakery and breakfast stop which bears more than a passing resemblance to Taos’s Michael’s Restaurant. Likewise, the often-arrogant yet self-deprecating fictional Jonathan Kepler himself in many ways resembles the author who created him, Taos writer John Nichols. (How much of this story is true autobiography, and how much is pure imaginative metaphorical invention? Only John Nichols himself knows the answer to that one, and I for one would love to ask him, though I doubt he would give a straight answer.)

Understandably, Jonathan’s daughter, Miranda, the grand kid’s mom, is skeptical about the educational value of Raven-speak, and lets Jonathan know her doubts in no uncertain terms. That’s not the only doubt Miranda has about her wayward Dad. In a hilariously cacophonous family gathering scene well into this hilariously bittersweet novel, Miranda blows a cork and unloads some four decades of filial exasperation and disappointment upon poor Jonathan, who is attempting in his own befuddled way to celebrate his sixty-fifth birthday with his family. Even Jonathan’s usually taciturn and stoic son, Ben, lurches into the melee, fists-swinging and bellowing. Jonathan, of course, is appalled, and only vaguely aware to what degree he himself has precipitated this emotional family melt-down.

You see, Jonathan wants nothing so much in the world as to be surrounded by his kids and grand kid, and perhaps to have his current girlfriend and some old pals also on hand. Yet, when he actually gets such good folks close, Jonathan seems unable to resist his inherent tendency to blow it. At one point, he even fears he may have unwittingly alienated his worshipful grand daughter just as he unintentionally alienated his children: “You would not believe how fast things can fall apart when promises are broken. I lost touch with my own children. I lost touch with the earth. And the years whizzed by like rooftops blown off by a hurricane.”

Seems that’s been Jonathan Kepler’s life story, at least according to Jonathan himself. He gets close to the emotional and material and familial prizes he so desires, then boots them out of reach, snatching defeat from the jaws of triumph. But if he could just gather his family around him and hike them up one more time to the daunting heights of thirteen thousand foot tall Spoon Mountain. Then all—including Jonathan himself–just might be redeemed. He might turn out to be a winner after all. Even if he has to match wits with a bedraggled and hungry bear to get there. Sometimes you do eat the bear!

What happens? Does Jonathan reach the heights he belatedly longs to reach? Does the bear eat him? Does he achieve any reconciliation with his daughter and other distanced relatives and friends? You will have to read this brief, fast-moving book to find out. Be warned, though, you will have to stop reading often to indulge yourself in chuckles, guffaws and outright belly laughs. And perhaps a few sympathetic tears for poor old Jonathan and his entropic world.

John Nichols is that kind of a writer. And On Top of Spoon Mountain is John Nichols at his funniest and most humanely engaging. This is John Nichols, one of our best story tellers, at the top of his game. In this book he confronts both his (and our) inevitable mortality and the awful prospect that the earth itself may soon die. He doesn’t back down from that ultimate facing up, and readers are very likely to enjoy climbing along with him. This is a bravely-written, highly entertaining and, ultimately, surprisingly encouraging read.

Bill Nevins writes for Z, Roots World, Eco-Source and other magazines and teaches English, Journalism-Communications and Screen Writing courses for the University of New Mexico (Valencia and Rio Rancho West campuses) and has lived in New Mexico since 1996. An active poet and grand-dad, he curates the annual New Mexico Film Festival and is profiled in the award-winning documentary film Committing Poetry in Times of War (available via HULU and Netflix). He can be reached at [email protected]