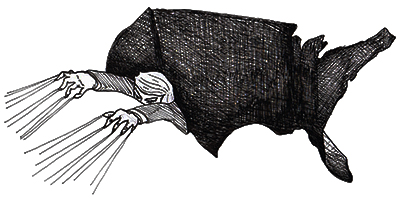

Back to Basics: Trump’s Counter-Revolution, Resistance, and Solidarity

The State of the Union speech by the new president, Donald Trump, has come and gone; so too his address before the joint houses of Congress. The shock of the 2016 election is lessening, it is time to take stock. Trump’s triumph evinces the worst of what Richard Hofstadter called “the paranoid streak” in American politics. That has a long tradition reaching back over Joe McCarthy to the heyday of the Ku Klux Klan to the “know nothing movement” of the late 1840s.

In our own time, President Barack Obama was surely correct that a straight line connects Sarah Palin’s nomination to Vice President of the United States in the 2008 election to the triumph of Donald Trump eight years later. The overwhelming majority of the GOP had moved to the far right long before he entered the race for the presidency. The establishmentarian opposition to its extremist agenda had already crumbled and Trump’s rivals in the presidential primary were equally reactionary. His victory was the product of their internal squabbling and an efficacious strategy predicated on divide and conquer. The right-wing upsurge was therefore not simply due to Trump. He was simply more radical in his rhetoric, less concerned with truth and the explanatory power of blatant bigotry for certain sectors of American society.

2016 witnessed a miserable presidential campaign. Unjust attacks on Hillary Clinton over emails, and baseless rumors of her supposed involvement in conspiracies of one sort or another had a terrible impact. But, still, Trump lost the popular vote by nearly three million votes – almost exactly the same number as that of the fraudulent votes supposedly cast (unanimously for Clinton) by three million illegal immigrants. But he won the electoral college with 306 votes. Undemocratic from its inception, designed to mitigate the power of everyday citizens and subvert the influence of states with larger urban populations, 2016 marks the second time in the 21st century – Governor George W. Bush’s victory over Senator Al Gore in 2000 was the first — that a conservative candidate used the electoral college to claim victory without a majority of the vote. In addition, a mushrooming scandal points to Russian interference in the election and collusion between Trump and Putin as well as the inner circles of the two leaders. Trump’s presidency is thus seen by many as illegitimate – and he knows it. This helps explain not only his sensitivity to criticism,

obsession with “leaks,” and rants about a media conspiracy directed against him, but also the flurry of activity that marked the first 100 days of his administration.

As for the liberal media, such as MSNBC, much of it pandered to supporters and condescended to opponents. They presented themselves as champions of honesty, tolerance, and social progress. Liberal media attacked Trump vociferously day after day –and always with the smug self-satisfaction of the “insider.” Too many jokes and groans greeted Trump’s daily disparagements of a “gold-star” military family, the disabled, women, Mexicans, and Muslims. Visions of higher ratings pushed Hillary ever more into the background thereby strengthening already existing feelings that the only justification for her campaign was that she wasn’t Trump. In short, other than for their devotees, the liberal media was a turn-off. Indeed, while mocking his supposed inability to raise campaign funds, the liberal media provided him with millions of dollars in free publicity and air-time while forgetting the old publishing adage: “better to be attacked than ignored.” They had little to say about Clinton’s “mistake” in supporting the Iraq War, her stance on the Libyan debacle (beyond her unfair treatment by Republicans over Benghazi), her calls for a no-fly zone over Syria and Sudan, her support for neo-liberal trade policies, or her anachronistic view of Russia. Liberal media deftly avoided discussing the sleaze associated with the Clinton Foundation, or the collusion between Hillary’s and insiders on the Democratic National committee in sabotaging the presidential campaign of Bernie Sanders. Unwilling to deal with such issues frankly, the liberal media actually heightened mistrust of Clinton and her candidacy.

But this didn’t matter much. Relentless attacks on the press and the media for its “fake news” and dishonesty marked the early days of the Trump presidency. European leaders of the far right followed his lead. That is the way of the “alt-right” and the neo-fascist. They also rely on the “cult of the personality.”

Unpredictability becomes a virtue: what the leader says in one venue is contradicted in another. Seeming incoherence enters into the formation of policy. Executive orders by Trump have targeted environmental regulations on coal production, and facilitated building the Keystone Pipeline (thereby inevitably raising carbon emissions), and placed climate change on the back burner as the hottest year on record passed into history. Elite friendly revisions of the tax code complement $1 trillion being devoted to infrastructure; free market policies and deregulation arise amid calls for protectionism; the dismantling of Obamacare is seemingly tempered by commitments to child care; restrictions on abortion are demanded while individual responsibility is privileged; building the “wall” and blocking Muslim and Latino immigration is threatened and then sweetened by a softer rhetoric; civil liberties are constrained, private prisons are praised, oversight of police control is lessened while freedom is proclaimed. Cabinet members are appointed because they condemned the offices they now lead and foreign policy is (purposely) conducted in haphazard manner.

The chaos is purposeful and the frenzied activity of the new administration seeks to throw opponents off balance. Progressives have responded in multiple ways and on multiple fronts. They have called for a special prosecutor over the Russia mess, employed legal actions in the courts, “truth squads,” bad publicity and mass demonstrations. All have contributed to keeping pressure on the new administration (with some success) and giving its faint-hearted and more opportunistic supporters cause to ponder their allegiance. Liberal media is focusing on the hypocrisy of one-time conservative critics of Trump like House Speaker Paul Ryan or Senator Mitch McConnell (R-KY) who have jumped on the president’s bandwagon. Republican unity has proven elusive. Election experts in the Democratic Party will surely investigate those regions of the “Rust Belt” that had previously voted for Obama but turned on Hillary Clinton and switched to Trump. The role of the left in the Democratic Party has grown. Senator Barbara Boxer (D-Ca) has introduced legislation that would abolish the electoral college –even though, to this point, it has gone nowhere. Beyond tactical concerns, however, it is important to recognize the magnitude of the current counter-revolution, the ideological confusions and naïve strategic assumptions prevalent among progressives, and the preconditions necessary for strengthening solidarity in the future. What follows are a few thoughts that might prove sobering.

Unfortunately, it would seem, little was learned from the Al Gore-George W. Bush presidential debacle of 2000 in which the former won the popular vote and the latter the electoral college while Ralph Nader (the consumer advocate) played the spoiler. This hotly contested election was ultimately determined by the pro=Republican Supreme Court. Admittedly, Gore lost his home state of Tennessee but, more importantly, 250,000 Democrats voted for Bush in the crucial state of Florida. Bush won there with 537 votes thereby sealing the election. Yet, it could have gone the other way. Nader pulled over 91,000 votes in that state and the great majority of his supporters, as he admitted in an interview for the Wall Street Journal (May 31, 2008) would have voted for Gore. That would have thrown the election to the Democrats—thereby probably sparing us the effects of a neo-conservative foreign policy, two wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, deregulation of markets, and wholescale attacks on the welfare state.

Third parties often raise issues and demands that establishmentarian parties ignore. Had Nader told his supporters a week or so before the election to vote Democratic in key and hotly contested states his project would have proven itself useful and legitimate. Unlike Bernie Sanders, however, he didn’t – and, whatever other factors might have existed, it cost Democrats the election. The situation was no different with the presidential candidate for the Greens, Jill Stein, in 2016. Others, mostly on the right, voted for Gary Johnson and his Libertarian Party, which received 4.5 million votes. A slim majority would probably have gone to Trump, but that is not our concern. The 1.5 million Stein voters considered themselves people of the left – and it was Democratic votes that they wasted. Numbers don’t lie. Trump won Michigan by roughly 11,000 votes—Stein received 51,000; Trump took Pennsylvania by 47,000 votes –Stein received about 50,000; and Trump’s margin of victory in Wisconsin was 22,000, where Stein received 31,000 votes.

Losing these three states would have deprived Trump of 46 electoral votes, leaving him with 260, or ten shy of the minimum necessary to become president. Apathy played a role. All in all, along with those who were not hindered from voting, but chose not to vote, less than 58% of those eligible to vote cast their ballots. Some believed it unethical to accept the lesser of the two evils; others embraced misguided beliefs in “the worse the better” while thinking that a Trump victory would usher in the revolution. There are still arguments flying around the Internet that question the need to take a position on conflicts between “neo-liberals and reactionary populists.” Their advocates apparently found it better to turn their backs on political reality – and, objectively speaking, apologize for the winner. Unlike old campaigns by communist and socialist parties, moreover, the Greens left nothing resembling a qualitatively more radical agenda on the table. They simply, again, played the spoiler.

All elections rest on choosing between the lesser of the two evils. Legislating an agenda always involves compromise. That would also surely have been the case for Nader or Green had they won. The issue is not what progressive social movement or interest group or even party is joined before crucial moments of decision take place. What counts is the decision to engage political reality when that moment of decision comes, when the stakes are high, the future hangs in the balance, and there is a choice between stubbornly standing alone or in solidarity with those who will assuredly bear the brunt of a more reactionary future. That is particularly the case in the context of a single-district winner take-all system that makes it virtually impossible for third parties to grow over time. The huge anti-immigrant demonstrations and women’s marches, mostly organized by those who chose to vote Democratic, demonstrate what should be obvious: solidarity with the disenfranchised and exploited is the precondition for opposing the new expressions of fascism.

Anti-fascism rests on the ability to fuse the defense of liberal political principles that impact upon all minorities with a socialist economic agenda that privileges the general interests of working people. That is true today no less than it was during the heyday of the Popular Front during the 1930s. But the requisite unity is arguably even more difficult to achieve under circumstances where interests are strong, political parties are weak, and so much of the discourse revolves around personal identity whose logic projects an ever-increasing specificity and particularism. Women took the primary role in standing up for women, people of color did the same, and so did gays. As cultural change flourished, however, economic inequality reached record levels. Indeed, whatever the positive cultural benefits it has achieved, identity politics has manifested a fragmenting dynamic that has had a negative impact on economic equity and class power.

Critical self-reflection and institutional analysis are necessary to deal with the problem. It will not vanish simply by chanting “the people united will never be defeated.” Fragmentation occurs in a way that is very much in accord with the vision articulated in The Federalist Papers (especially Number 10 and 51) written by James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay in 1787-88. So, for example, women’s liberation originally spoke to all women. If a woman is also gay, black, and working class, however, it is questionable whether her specific identity can be determined by the National Organization of Women or any of the more generic original groups. A person can obviously share multiple identities and new forms of hybridity or “intersectionality” will constantly appear. New organizations then become necessary to represent them. Each will thus appear as a (quite traditional) “faction” intent upon privileging the interests of its own clientele. Interest groups can often agree on the need for specific reforms. They can work with established political parties and cooperate in single-issue coalitions – often to great effect. With the multiplication of lobbies and interest groups, however, comes an ever-greater competition for resources and loyalty. Alliances rise, fall apart, and then rise again so that there is a constant need to reinvent the wheel. Class drops out (or turns into yet another identity) so that it becomes ever more difficult to comprehend the workings of capitalism. In short, the whole becomes less than the sum of its parts.[1] And that defines the current situation.

Identity formations tend to highlight the sufferings of one victim as against those of others. Such an aim is embedded in the structure of interest groups and, of course it facilitates a policy of divide and conquer. That has always been of importance since the bigot rarely targets only one group but, instead, hates in clusters and often employs interchangeable stereotypes. Today, however, the situation is particularly dire since the old rhetoric of prejudice is being supplemented by seemingly respectable justifications: curtailing voting rights is not discriminatory, for example, but a way of preventing (non-existent) electoral fraud; shrinking the welfare state builds character and individual responsibility; making taxation more regressive fosters investment; attacking historical “revisionism,” evolution, and abortion rights protects tradition, religion, and the family. Nevertheless, if the rhetoric of bigotry has changed, its traditional targets haven’t.

A coordination problem exists. Fashionable claims that reliance on unifying categories, universal values, and institutional or “grand narratives” tend to squash “difference” is profoundly misguided. Exercising personal identity actually depends upon the extent to which civil rights are operative and a state is required to sanction their employment. Adherence to the liberal rule of law is not simply an add-on to identity or even social equality—but decisive. Not only does it place protection of the individual above the state but it also serves as the precondition for establishing reciprocity among working people in all social movements and identity groups. “Identity” is organized politically not by social movements and idealistic activists but, instead, through interest groups whose professional leaders are intent upon privileging the material concerns of their members over those with other identities. Solidarity, in short, is usually institutionally short-circuited through the moral economy of the separate deal. That is what the liberal rule of law both legally and ethically rejects: it treats all identities and social movements equally and, at least in formal terms, refuses to privilege any of them.

The same is necessary when it comes to class politics. As things now stand, the working class is identified with older white industrial workers living in regions like the Midwestern “rust belt” (who tended to vote for Donald Trump). This makes things simple: the working class is given a “natural” and empirical identity that lets it be understood in the same terms as women, people of color, gays etc. Class becomes just another identity among a host of (transclass) identities. And, since loss of electoral votes from the rust belt cost the Democrats the presidency the common (if simplistic) wisdom suggests the need for policies that target the (white) working class and bring it back into the fold. But the conceptual and practical mistake is obvious. Privileging that sector of the working class will alienate other sectors. There are black workers, women workers, and gay workers. The working class surely also includes those office workers and others whom one encounters on subways during rush hour. The need exists for coordination among progressive forces and new categories that cut across those cross-cutting cleavages.

Fostering unity among working people calls for understanding the working class not simply in arbitrary empirical terms but as the class that sells its labor power on the market in conditions not of its choosing —- and feels its exploitation in doing so. “Class” should offer a perspective on unity among the disenfranchised and exploited that no other “identity” can provide – if only because it blends (universal liberal political) principles with (universal economic and social) interests. That is the type of unity required to fight the counter-revolution. Its mass base will undoubtedly exist in the cities where resistance will most likely congeal against a counter-revolution that, like its predecessors, is lodged in the less economically developed and non-urban parts of the country. Class solidarity today calls for confronting what Marx termed the “political economy of capital” with the “political economy of labor,” and inventing a class agenda that clarifies the material concerns of working people within each identity-based social movement without privileging any. Such an outlook requires what in Socialism Unbound I termed “the class ideal.”

Reducing the working class to the white industrial working class defines the universal in terms of the particular. And it is no accident that the most anachronistic elements should become the symbol of the working class given the backwardness of the American labor movement. Class is a logical derivation of the capitalist accumulation process and it cuts across other (transclass) identity formations thereby creating conflicts of interest within and between them. So, for example, the elitist preoccupation of Hillary Clinton’s supporters with cracking the “glass ceiling” blinded them to the concerns of poor and working class women who were far more worried about avoiding the economic pitfalls of the trap-door. Just as commitment to the generalizable principles underpinning the rule of law makes possible the exercise of diversity, indeed, targeting generalizable interests of the working people makes possible the exercise of class solidarity. There are no guarantees of success. The class ideal is nothing more than an ethical imperative born of political need.

Thousands and thousands of individuals are engaged in the seemingly countless groups that comprise the progressive community. The problem is not apathy as the huge demonstrations that have marked every political ebb and flow since the 1960s will attest. Especially in periods of economic downturn and rigid labor markets, such coalitions are constantly threatened by what might be termed the moral economy of the separate deal. Yet, unity cannot be imposed from the outside by some vanguard organization. Only activists within each of the social movements and engaged in identity politics —– those whom Foucault called “empirical intellectuals” — can effectively articulate the programs necessary to further unity. Such is the dialectical irony of our times.

A new political culture is confronting argument, evidence, and science with dogma, faith, and intuition. Intellectual sloganeers are already speaking about the “post-truth” society. The Other is being held in contempt; Immigrants are in danger of deportation; a useless wall separating the United States from Mexico is being built; Syrians and those coming from crisis torn nations in the Middle East are in danger of being sent back; protectionism is deluding workers and straining relations with other nations. Fear of the Other and the crudest stereotypes are being fueled by paranoia, hysteria, and resentment. Trump seems to view foreign policy as a smorgasbord; he has taken his admiration for pre-emptive strikes from George W. Bush, his belief in “no-fly zone” in Syria from Hillary Clinton, his super-power fixations from liberal “realists,” and his contempt for international organizations such as NATO and the UN from the neo-conservatives. Trump’s conspiracy fetishism speaks to provincial feelings of exploitation and ingratitude by the world community. His use of the slogan “America First!” projects the vaguest possible notion of the national interest even as it highlights the chauvinism that marked his presidential campaign.

Trump and his followers have also instigated what might be termed a “post-truth” perspective. Numerous organizational fact checkers report on the far more numerous lies and distortions of empirical reality that have shaped the president’s pronouncements and influenced policy from his anti-immigrant stance to denial of global warming to his assault on Obamacare. Experts, intellectuals, scientists, and the general commitment to education are now the “enemy of the people.” Trump’s use of fabrications and falsifications of fact, his own conspiracy fetishism, and the psychological projections of his own actions upon opponents, all contribute to his fundamental aim that is common among both bigots and authoritarians: avoid engagement in a critical discourse and the need to justify arguments and claims. Privileging “street smarts” is the traditional way in which fascists have indulged the elitism of the mob. Milquetoast liberals, who warn against “demonizing” Trump’s supporters, misunderstand not merely the direct authoritarian threat they pose but the style of their public stance. Of course, it is true that some are simply misinformed and embrace the new authoritarian in good faith. But that doesn’t change matters. The belief that they have been somehow carried away and not responsible for the choice that they made is worryingly reminiscent of the way in which it was claimed that the German people were somehow mesmerized by Hitler and that, as Hannah Arendt would have put the matter, they had lost the ability to “think.”

But they didn’t lose that ability. Such a claim actually deprives fascists both today and yesterday of their culpability as well as, ironically, their free will as individual subjects. Supporters of Trump and the Tea Party made an ethical and political choice. They chose to endorse thugs and “think” accordingly. Authoritarianism, bigotry, and intellectual thuggery, or the elitism of the little man, have always exhibited a certain elective affinity with one another. Progressives today must defend liberal principles from those who hate them—and who have achieved power. Economic programs calling for building infrastructure through “public-private” means have always been easy for fascists to support. It is a small price to pay for the success of an authoritarian politics. Trump is no classical liberal tied to civil liberties, free markets, and a small “watchman” state. He and his friends want a strong state – so long as they are not held accountable for the ways that they exercise power. Principled political opposition is required. Progressives must refashion the enlightenment legacy for our time, privilege its liberal and socialist traditions, and promulgate a new cosmopolitan sensibility. This constitutes a complex pedagogic and political task. Nevertheless, progressives need to meet the challenge if their more humane outlook is to reclaim its influence and rise like a phoenix from the ashes.

Stephen Eric Bronner is Board of Governors Professor of Political Science at Rutgers University and an Editor of Logos. His books include The Bigot: Why Prejudice Persists (Yale University Press); Moments of Decision: Political History and the Crises of Radicalism (Bloomsbury), and Reclaiming the Enlightenment: Toward a Politics of Radical Engagement (Columbia University Press).