Henry A. Giroux, America at War with Itself. City Lights Books, 2016

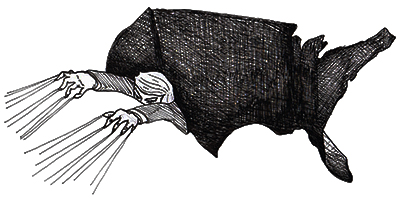

Henry A. Giroux is a prolific scholar and public intellectual best known for his work in the field of “critical pedagogy” and on issues commonly grouped under the hypernym: “social justice.” His latest book, America at War with Itself, offers readers a way to “see through” the “dark clouds of authoritarianism” gathering over America, Europe, and the world, while “point[ing] to alternative pathways offered by critical pedagogy, insurrectional democracy, and international solidarity.” In a brief Foreword written by Robin D.G. Kelley, Giroux is described as “the intellectual descendant of Antonio Gramsci,” a revolutionary thinker who diagnoses the ills of neoliberalism, militarism, authoritarianism, environmental degradation, racism, nationalism, violence, civic illiteracy, and the collapse of the public sphere. While such claims may be a dash hyperbolic, there is real value to be found in America at War with Itself, particularly as a readable summary of some of our most pressing social, economic, and political problems.

Giroux strives not only to recount the most unsettling current events but to contextualize them with reference to the broader ideological landscape of twentieth and twenty-first century America. The book is praiseworthy for bringing together analyses of the rise of Donald Trump, the victimization of Sandra Bland, the water crisis in Flint, Michigan, America’s gun epidemic, ISIS and global terrorism, the economics of austerity, right-wing political movements, the relationship between police and military organizations, the degradation of journalism, and more. These events and trends are too often presented and perceived as isolated or exceptional incidents. Indeed, one of Giroux’s most important theses is that it is crucial “to connect” these issues to the institutional structures that propel them, to the ideological system — what a successor of Gramsci might have called the superstructure — that both shapes and is shaped by them, and to the individuals who experience them first-hand.

The book — divided into eight chapters and four parts — begins with “Donald Trump’s America,” Giroux’s signature example of “the menace of authoritarianism.” The menace of Trump or Trumpism, however, is “not new,” according to Giroux, but has been hiding in plain sight for decades, as militaristic and corporate forces have overrun civic and political spheres, culminating in a fascistic politics of “the unthinkable.” Giroux then turns his attention to four deadly political ills: lead-contaminated water in Flint, Michigan (and other areas), America’s epidemic of gun violence, the brutal treatment of Sandra Bland at the hands of Texas State Troopers, and the 2015 terrorist attacks in Paris, France. While these examples — along with the depths of their analyses — are quite varied, Giroux strives to connect them by reiterating in Parts 2 and 3 what has come before: that racialized class warfare, violence, and a culture of fearful ignorance define today’s version of what Albert Camus once called an état de siege [state of siege]: a political, moral, and psychological state of human degradation. Chapter 7, “Paris, ISIS, and Disposable Youth,” co-authored with Brad Evans, stands out in its development of a compelling theory of how attitudes and policies that rely on the premise of intractable conflict both recruit and attack young people, robbing them of alternative imaginations or “alternative image[s] of the world.”

In spite of the book’s usefulness in cataloging the challenges before us, however, what really seems “to connect” the tragedies Giroux describes and the “dark clouds” from whence they are distilled is that progressives are against them. While there are good reasons to be “against them,” the adversary Giroux sets up in his book is hydra-headed, invested with an almost demiurgic quality, and yet remains so vague as to inspire confusion. For instance, while Giroux is surely correct that the dangers we face are not “new,” they are most often attributed to that preferred whipping boy of contemporary progressives and academics: “neoliberalism.” The concept of “neoliberalism” has been used and abused to the point of meaninglessness, serving now primarily to unite Leftists under a common banner. Giroux, himself, holds “neoliberalism” responsible for plutocracy, militarization, racism, xenophobia, sexism, celebrity worship, entertainment-culture, the degradation of public education, the erasure of historical memory, the elimination of public spaces, the absence of solidarity among citizens, the privatization of time, and more.

And “neoliberalism” is not the only slippery signifier relied upon by Giroux. What is denounced as “fascism” on one page is decried as “authoritarianism” on another, “totalitarianism” on another, “demagoguery” on another, and “tyranny” on another. In Chapter 3, entitled, “The Menace of Authoritarianism,” there is even a subsection entitled, “The Menace of Totalitarianism.” Not only does this relationship of sub- and super-ordinacy seem counter-intuitive, but nowhere in the book can the reader find a description of (Giroux’s understanding of) the relationship between these important concepts. Later, Giroux argues that “totalitarianism throws together authoritarian and anti-democratic forms that represent a new moment in American history.” The claim that we are facing a “new” moment in history not only seems to contradict Giroux’s central thesis that current events are “not new,” but is exemplary of the confusion we face if we take seriously ideas like totalitarianism, authoritarianism, and democracy. In calling attention to these discrepancies, it is not my intention to focus excessive attention on semantics, to be petty, or to trivialize the issues treated throughout the book. On the contrary, we learn something vital by attending to Giroux’s language.

While it is well beyond the scope of this brief review to offer definitions and distinctions between concepts such as fascism, authoritarianism, tyranny, and totalitarianism, they may be usefully distinguished by the relative importance of charismatic leadership, the influence of nativist or racist political dogma, the degree of state-intrusion into private lives of citizens, the relative influence (or lack thereof) of the rule of law, and several other identifiable (although not always quantifiable) variables. To use such terms interchangeably suggests that Giroux’s attempt to “connect” issues and problems may not be so much an intellectual endeavor as an emotional one. That is, the goal would seem to be to affirm the enemy, in all of its guises, to forge emotional identifications between readers and victims, and to form a sort of loosely-knit group defined by opposition to the overwhelming evil objects named and re-named throughout the book. Put simply, when terms and concepts like these are muddled in this way, they serve primarily to reassure us that we are in danger, that we are together, and that we are on the right side.

For instance, while it certainly holds rhetorical appeal, Giroux’s decision to call the Flint, Michigan water crisis an act of “state violence” and “domestic terrorism” seems intended to rouse us to anger more than to help us understand the (potentially interesting) connections between neoliberalism, the politics of austerity, racism, and terrorism. If we wish the idea of terrorism to be at all meaningful — and almost any reasonable definition involves terrorism’s symbolic nature: its emphasis not on the infliction of injury but on spectacular violence that engenders widespread fear and psychological distress — then naming the Flint crisis “terrorism” without further explanation teaches us little about the Flint crisis and terrorism. To say it another way, the “connection” Giroux strives to accomplish here is not a connection based on understanding but on outrage and anger. If both terrorism and poisoned water unite us in outrage in anger, then perhaps we need not think about whether it is reasonable to suggest they are the same. Or, if the goal of making this connection is, as I have suggested, an emotional one, then perhaps we would rather not think about it.

Giroux does not reflect on the irony that, in a book dedicated to resisting “the unthinkable,” antagonizing forces are made indecipherable and, to that degree, “unthinkable.” This unacknowledged internal tension, however, does not necessarily decrease the book’s value, at least not if we can read Giroux “against the grain,” as Terry Eagleton would say. Indeed, such a reading is illuminating, for it reveals that even a brilliant mind, like Giroux’s, engaged in a noble pursuit, such as formulating opposition to totalitarianism, may fall victim to patterns of thinking and emoting that are, themselves, totalizing. Perhaps the most obvious example of this is that the very title of the book, “America at War with Itself,” turns out to be nothing but a slogan, repeated eight or nine times, but not once examined or explored. It is difficult not to remark the irony in the book’s call to judgment when the reader is asked to reflect on “the banality of evil” and on the figure of Adolf Eichmann, whom Hannah Arendt famously condemned as a man who could think only in slogans.

In Part 4, which contains a single chapter, we find Giroux’s proposed solution to the overwhelming dangers we face. Giroux exhorts us to implement a “resurgent and insurrectional democracy,” although this concept is never defined. If we take “resurgency” and “insurrection” at face value, we are left to wonder whether blending these practices with democratic values would require the destruction of existing civil and political institutions, and even whether the combination of democracy, resurgency, and insurrection could uphold the basic tenets of democracy, such as political equality and the possibility of collective deliberation. But Giroux quickly returns to more familiar ground, the need for a “critical pedagogy,” a complex and controversial term popularized by Paolo Friere and Giroux, himself.

By “critical pedagogy,” Giroux means, among other things, the renewal of an “ethical imagination,” a concept that is puzzling but potentially rich. What is surprising is that the complex but possibly illuminating relationships between the imagination, criticality, and ethics are not explored here. Instead, the reader finds a description of a pedagogy that seems quite uncritical. For Giroux, pedagogy must be defined as “a moral and political exercise” in order to “‘refresh the idea of justice going dead in us all the time,’” as the poet Robert Hass would have it. Learning to be a “skilled citizen,” according to this pedagogy, means adhering to a particular set of moral and political values, which include pluralistic democracy, socio-economic egalitarianism, non-violence, and the importance of “service to a greater collective good.” And while many of us would likely applaud these ideals, the imposition of specific moral values upon any pedagogy should prompt serious questions about what we mean by terms like “critical,” “ethical,” and “imagination.”

If a “critical” pedagogy means that students are instructed to identify with the oppressed, to hate oppressors, and to dedicate themselves to particular forms of moral and political activity identified as “good” by their instructors, then it replicates, at the most fundamental level, the dynamics of totalitarian education. Even the notion that a pedagogy should “provide the conditions for students to be engaged individuals and social agents,” predetermines the meaning of “the good” as social “engagement” and “agency,” seemingly neglecting other ethical and democratic values, such as autonomy, solitude, and resistance to the imposition of any (group) identity.

Related to the democratic and pedagogical renewal Giroux proposes is a long list of needed intellectual, cultural, and global “changes” which, while laudable, lack definition and explanation. In addition to the renewal of “public spaces,” Giroux implores us to create “a new language,” a “new discourse,” new “global alliances,” a “new form of politics,” a “new political conversation,” and “new forms of agency.” We “need to invent a new system from the ashes of one that is terminally broken,” we need an entire “rethinking [of] the space of the political,” and we need always to “connect issues,” for “there has never been a more pressing time to rethink the meaning of politics, justice, struggle, collective action, and the development of new political parties and social movements.” So, faced with the specter of “the unthinkable,” urged on by indistinct and overwhelming “dark” forces with too many names to count, we must embrace the hope that an all-encompassing personal and political renewal can be accomplished by enforcing a progressive pedagogy focused on emotional identification with oppression, victimization, and injustice. Here, the language of resistance becomes difficult to differentiate from the language of totalitarianism.

The admirable scope, ambition, and intellectual dexterity displayed in Giroux’s latest work will not surprise his fans. It may well become an important reference for those seeking “connections” between seemingly disparate instances of social and political injustice in our time. But Giroux’s book also seems intended to coax the reader to align his or her judgment with Giroux’s, or, rather, to solidify a congruence of judgment already established. But there remains (or there must remain) a difference between the activity of critical thinking and the activity of solidifying moral judgment, for, as much as we may oppose our political adversaries, we can not preserve a space for critical examination and genuine opposition if our moral judgments and group identities are pre-formed and solidified via emotional identification, or, to paraphrase Christopher Bollas, never thought but deeply known.

Instead, we must recognize that moral judgment, while clearly necessary at times, can also contribute to thoughtlessness and unthinkability, that morally judging ourselves and others can be a means of repressing thought and attacking ethical being and relating. While engaged in the activity of moral judgment, it is tempting to neglect nuanced understandings and self and other and to seek to shore up the hatefulness of the enemy by calling him, her, or it (many) names and by imagining him, her, or it in exaggerated, overwhelming, and even grotesque forms. In totalitarian regimes, the values upheld by the ruling powers pervade all aspects of public and private life, even thought. But in our hurry to critique and combat totalitarianism, we, too, may be drawn into a cycle of short-circuited thought, facile moral condemnation, group-oriented political identities, and a kind of symbolic violence by which we call out all the “dark forces” of the world, only to find that, by taking this stance, the values and principles upon which our condemnations are founded have become more, not less, obscure, and the “dark forces,” themselves, have become more, not less, difficult to resist.

In one sense, Giroux’s work holds a certain affinity with Paul Potter’s famous exhortation at the (1965) March on Washington, D.C. to “name [the] system” that wages war on the Vietnamese people, that disenfranchises and impoverishes its own citizens, that creates “faceless and terrible bureaucracies” in which we work and live, that “consistently puts material values before human values,” and more. “We must name it,” Potter declared, as the first step in a longer list of imperatives. That is, we must not only “name it,” but, then, “describe it, analyze it, understand it, and change it.”

If, with concepts like “neoliberalism,” we seem to have come closer to “naming” the system responsible for tragedies suffered in contemporary America and around the world, we may have also discovered that “naming” the system is not enough; indeed, that “naming” it may even inhibit our ability to “describe it, analyze it, understand it, and change it.” In an irony shared with Giroux, Potter argued that we must “name” the system precisely in order to “to build a democratic and humane society in which Vietnams are unthinkable.”

While Giroux’s latest work shares the urgency and sincerity of Potter’s speech, both force us to ask ourselves whether the emphasis placed on “naming” (or, as we like to say: “calling out”) intolerable aspects of our political, social, and cultural institutions — as “neoliberal,” “fascist,” “authoritarian,” or the like — offers real help in achieving our greater objectives: developing and sustaining the personal and political capacities needed to understand, critique, resist, challenge, and ultimately change those institutions.

What would make Giroux’s book even more valuable would be some “critical” and reflexive attention paid to the possibility that “naming” the ills of the world may reflect not only a desire to combat them, but also a (tragic, ironic, or perhaps even unconsciously self-destructive) effort to make them unthinkable. The effort to make something unthinkable reflects an ambivalent intention: It means not only to make something vanish from our memories and imaginations, but to keep that thing around in a form so ill-defined that it is capable of containing all that is bad or wrong. This “dark side” of our opposition to the “dark forces” we face makes it likely that we will develop an emotional dependence upon unthinkable evil forces and our endless struggle against them.

To be able to think them, on the other hand, offers greater opportunities to break from the past and to give up on this ultimately unproductive relationship with the evil forces that unite us. Of course, to comprehend our situation and to re-imagine the terms of our struggle may be to give up on powerful emotional identifications and group affiliations that provide comfort, particularly in times of crisis. Thus, in facing down what appears to be an authoritarian revival, we may find that the first struggle is an internal one: to reflect upon and resist the temptation to totalize ourselves and others, a process by which, paradoxically, the enemy is obscured while the legitimacy of our opposition is made crystal clear.

Matthew H. Bowker, Ph.D. is Clinical Assistant Professor of Humanities at Medaille College in Buffalo, NY. He is the author, most recently, of A Dangerous Place to Be: Identity, Trauma, and Conflict in Higher Education (with D. Levine, Karnac, forthcoming, 2017), D.W. Winnicott and Political Theory: Recentering the Subject (with A. Buzby, Palgrave 2016), and Ideologies of Experience: Trauma, Failure, Deprivation, and the Abandonment of the Self (Routledge 2016). He welcomes communication at mhb34@medaille.edu.