Beyond the Collapse: Clearing the Ground for What is to Come

Regimes in their death throes, attached to and driven by no longer viable forms of institutional power and psychosocial organization, do not go quietly. To the contrary and to the horror of those who watch, and see, they relentlessly tighten their faltering grip using every dark bit of leverage those forms allow. In the process, ever more blatantly and shamelessly sharpening the contradictions – and their sentence of fatality – awaiting, ever more conspicuously they act out the condemnation of history that they have come fatalistically to expect.

“It shouldn’t be that way.” “Isn’t there something we can do to stop them?,” you say, the wanton cruelty, the gloating callousness to others’ basic humanity, to the fate of the world, and the species, even (especially?) to their own ultimate survival? What accounts for such virulent irrationality beyond Freud’s mere positing of a primal death wish, an explanation refuted by the continuing and expanding presence of life on earth over the vast millennia? Always in a Shakespeare tragedy, all the lead characters’ bodies strewn about, someone must pick up the pieces and carry on.

We have come, for some suddenly, into the dynamic space between Thucydides and Plato at the origins of Political Theory. Perhaps we witness again the collapse of the Athenian dream of release from the circularity of fate into linear progress probingly chronicled by Thucydides, a dream whose very hubris ensured for that writer the same outcome as the early Greek tragedies. Yet it was Plato who pointed us away from such a narrow framing, who insisted on what Hegel following Augustine would inscribe in history, that the destinies of great projects flow not from their geopolitical aggrandizements but from the ideals that are shaped in their ascent (and often furthered by their geopolitical failure and cultural decline).

No one would conclude from this that the lead actors in this tawdry tale of implosion have an inkling of their role as the tarmac of history. They have seen a vacuum open at the center of the American world-historical – in the negative and positive sense – project, and have leapt to fill it. “Surely the center will hold,” those once-progressives intent on defending Obama’s quixotic and myopically flawed political geometry assert. “This is just another swing of the pendulum,” we hear, “by which America provides space for political and cultural differences in its big tent.”

One may want to respond that every regime tolerates its internal tensions until it doesn’t, that the present crisis is upon us because most Americans took for granted that the center would hold despite the vast erosion of core political, legal, economic, and psychosocial structures over several decades, that even as these seismic changes led them to withdraw their faith in the classic American institutions and values they preferred to indulge in a massive feeding frenzy, assuming the old order would carry on without their fealty. Instead of boldly embracing their own shift in values and aspirations from a ruthlessly competitive, hierarchical and consumption based society, they turned away from their own recognitions, their own new imaginings, counting on the elites to keep the ship on course and protect them from having to really identify new ways to live and new institutions and social practices to ensure the advance and consolidation of the transformative post-industrial project.

And now, in shock, Americans want to blame the elites for grabbing the whole thing they were given, we called it euphemistically and enthusiastically marketizing, incentivizing, privatizing, deregulating, the schools and the environment, and the sciences and the universities, and the financial markets and the military cadres projecting global power and force. We say to these elites they have no right, but they show us the warrant we signed – “hold onto the center for us while we bowl alone, and just make sure that we do not get a call in the middle of the night that something has gone horribly wrong, let us sleep the sleep of the well-fed and the complacent, of moralists without morality and pietists without religion and armchair warriors armed with 401K’s and a place in Florida.”

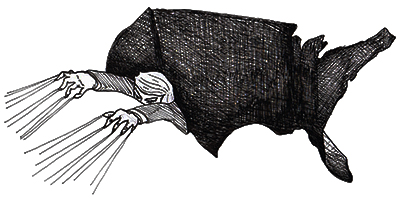

Well, the wakeup call has come anyway, that we are in the midst of a constitutional coup, that the center – the legislative and judicial and state governmental and electoral and administrative checks – has flown the other coop, that it is now a one-party state, the envy of an earlier Latin America, poised through control of the system and the states to repeal the twentieth century and force through constitutional amendments that would make Pinochet blush. And why the center did not hold, why there was no center there to hold, is just the first step in a process of painful – and yet ultimately liberating – realizations.

The collapse of the consensus about the viability – and indeed the ultimately validity – of the American experiment as the cutting edge of modernity dates from the early 1960s. It was not conservatives but cultural radicals and political progressives, most eloquently expressed by an emerging generation of youths and young adults in the Port Huron Statement, but also by Fromm, Riesman, Galbraith, Marcuse, and a host of others cultural analysts, who recognized that in the unprecedented productivity of post-industrial society opportunities for post-work priorities, creative and innovative ways of living, unprecedented distributional justice and self-realization, community and democracy were more attainable than ever before. They in turn challenged the addictive consumption and routinized work, the atrophied selfhood and lack of authenticity and meaning, of dreams and aspirations, signified in the end of ideology and the installation of the organizational liberal behemoth as the ultimate American dream. Above all, the new measure of a life well lived was now the extent of self-actualization within meaningful lives and communities, no longer the effectiveness of self-repression and self-routinization and self-abandonment in the name of future commodified returns in status, power, and privilege.

Set loose by modern post-industrialism and the consumer society from traditional normative (superego) expectations of moral rectitude and the utilitarian demand for efficient and system supporting practices of the Protestant-liberal work ethic, the initial dreams fostered by release led many to embrace the immediacy of unconstrained gratification. Inattentive to the long-term complexities and challenges of institutional and psychosocial transformation, they allowed indulgence to become an end in itself, further exacerbated by the consumerist mobilization of hedonism. As a result, the momentum for significant change stalled. Many radicals and progressives began drifting toward mainstream values and certainties, not out of conviction but rather self-doubt, pragmatism, and disillusionment.

And yet, with the cogency of the critical analysis of the increasing emptiness and misdirection of American life and the realization that everything was now permitted, the invisible internalized tie lines holding most Americans to their traditional commitment to its values and institutions dissipated. Suddenly, the message spreading through the culture was that limits and restraints were only for those too compliant to indulge. Even the conservative defenders of traditional psychic and behavioral arrangements from more repressive backgrounds, both elites and populous, heard the call. With little capacity to or interest in forging a new common ethos, this large constituency could not resist acting on the temptation to seek revenge, to lash out against the “destroyers” of their way of life, to reassert their sense of dominance, often patriarchal, against those who were trying finally to improve their life conditions or assert their individuality. At a much deeper, largely inaccessible level, rage also erupted from betrayal by the system that had stunted their lives and sense of possibility, that had fed them the rhetoric of the American dream with only fishhooks inside to grab possession of their souls. The irony was that this reactive and reactionary, destructive and self-destructive, campaign that increasingly fuels American life was equally the product of consuming appetites.

The result was a release of desire through the culture without any impetus toward self or social transformation or even normalizing order. These conservative turned reactionary legions were easily manipulated by elites intent on consolidating power. Mobilizing disaffected constituencies with a serial con game, promising the fulfillment of unrealizable apocalyptic fantasies of return to an imagined sense of unlimited privelege and promise from Reagan to W to Trump, they undertook a concerted effort to disassemble the system and its institutional limits on unrestrained power. Meanwhile progressives and liberals and other cultural experimenters, lacking any alternative vision and fearing the oncoming deluge, became (quixotic and half-hearted) defenders of the system from which they had just pulled the rug of legitimacy. Pursuing meritocratic careers and similarly pushing their young into the system of institutional rewards, they turned to the accumulation of technocratic credentialism and administrative leverage.

To what end? As Thomas Frank has emphasized in Listen, Liberal, the meritocratic pursuit was no longer attached as in the past to the rise of administrative cadres who had seen their mission as advancing anti-plutocratic forms of social justice and administrative fairness. The new agenda was rather to institutionalize ‘rational’ and efficient and cost effective social policies that would legitimate their role as the managers of power. But lacking any broader ends for the society as a whole, the meritocratic center no longer maintained its connection with any electoral base or constituency with and for whom it labored. It thus became its own form of privilege for itself and its progeny in contest with plutocratic privilege, fighting up the organizational ladder and mobilizing its children with every benefit and form of social capital to commandeer the social capital for competitive advance. Exploiting their advantages over those young who came from the sectors with less social capital they had once sought to help, they now regarded ordinary citizens as less successful or worthy or deserving of help, for they had failed in the meritocratic Hunger Games. In this way, the link to the larger public was further severed.

The problem was that, lacking goals and constituencies, the meritocratic sector has been easily co-opted by the organized and determined plutocratic sector which has carried out a forty year (and longer) campaign for control. For it is this sector which provides jobs, careers, rewards and status, organizational and governmental leverage, cultural and non-profit funding and the many forms of university research and competitive branding that now sustain the careers of talent. And with the merging of government and plutocracy now fully consolidated, its exertion of control over the meritocracy will enter a new phase of overt dominance. This was the reality that Hillary Clinton could not either counter or address, that her predecessors Bill and Barack rendered inevitable by deferring to the corporatization of the nation and the isolation of the meritocracy from the rest of society

Ironically, this shift leaves this once-liberal sector more closely allied to the organizational and corporate elites than to sectors in need of change. They have no independent base in their position of subservience to pursue either an egalitarian institutional agenda to assist descending white and minority constituencies or a cultural, psychosocial agenda of greater post-industrial self-realization and humanized communities. Moreover, as the Reaction gains steam and the effort to repeal the New Deal proceeds, the result is a progressive relapse to a focus on basic living standards reminiscent of the first half of the twentieth century and the utter absence from public discourse of demands so obviously needed to address the structural shifts of post-industrialism with new social priorities.

The present situation would appear to be one of great danger. In a condition in which both internal and systemic restraints have been seriously breached and even undone and appetitive monomania carries its own justification, the elites believe they can mobilize mass affect for a plutocratic consolidation. The notion that mass expectations can be reduced now that appetite is out of containment is hard to imagine, particularly given that it is now in service of unbounded elite appetites and agendas. Given that these elites are themselves out of control – and have been increasingly since Reagan, however, it is hard to imagine them convincing anyone of the need for moderation. With fear of elites (the classic strategy of repression) of limited mobilizing value to commandeer a formal if corrupt popular society, the more likely course will be diverting mass appetite from recognition of mainstream decline toward the fear of others.

The likelihood, in other words, of a traditional authoritarian, neo-feudal solution of popular compliance is substantially lower than of need to appease a mobilized public with at least some faux populist trophies. To appease mass appetites without offering anything of substance that will even slightly diminish their Midas-like hunger suggests the path of least squares toward war, scapegoating, repression of the marginal, the Thucydidian trajectory of imperial limitlessness, displays of naked power and will, at first costing only speeches but very quickly to the fatal drain on treasure and soul that empires eventually accede to with the inevitable – sooner rather than later – overreach.

Where does that leave us? A window into the underlying dynamic is provided in the 2016 film Neruda by Pablo Larrain. This cat-and-mouse chase featuring the Chilean poet and a member of the fascist police explores how fascism is driven by no vision of its own but rather by its resentful inability to imagine and create lives of meaning. The hunt for Neruda represents the effort to expunge the tellers of transformative and humanizing stories because of this moral and spiritual vacancy, their vast cisterns of nihilist self-inadequacy (and really envy) fueling the underlying rage and violence. Once we understand that the Reaction is driven by the elite mobilization of uncontrollable rage and envy, we can get a better sense of how historically outmoded movements mobilize and gain power.

The fact that this movement is immune from questions of real outcomes or even real goals beyond revenge, from the logic of governance or the urgent global issues now accelerating, from the contradictions, hypocricies, and self-aggrandizing irrelevances of its leaders, makes it necessary to address the underlying feelings of envy, of being cut off, starved, ruthlessly deprived, of the possibilities of genuine self-actualization that other sectors seek to realize. This Claggart-like desperation to immobilize and demean others, to beggar all who yearn for well-being and wholeness, an insatiable need to destroy anything that hints of hope, now shorn of its theocratic apocalypticism in naked aggression, reveals what we are up against. Moreover, as we watch this culture that has everything but its own inner compass and feels deprived, hollowed out, betrayed by large dreams that have turned to dust, that indulges in the immediate because it has no time line for the future, pursues a scorched earth campaign because it has nothing to plant, we must know that the system that we have long realized was at the end of its days is preparing its own final acts.

This dynamic of being caught by historical change, unable to adapt, is one that lies behind similar self-destructive movements. Most notably, Wilhelm Reich described the mass psychology of fascism as the reaction of vast groups of Central Europeans raised with traditional authoritarian character structures who were unable to adjust to the collapse of village economies and the rise of individualistic modern society with its meritocratic capitalist industry and fluid and morally unregulated urbanism. We can see here how elite class warriors are playing the cards of race and gender war to mobilize groups unable to adapt to the loss of male and white psychosocial status with the rise of a post-industrial, technocratic society. Humpty-Dumpty, the privileges attaching to traditional American life, cannot be put back together nor its provincial incentives and shelters maintained as its own best and brightest leave for the city and technocratic lives, leaving wastelands of neglect and futility.

This paradoxically makes them the perfect lever for continual mobilization. These are groups that never came to terms with modern liberal individuality, and have fallen continually behind as they have felt the nation taken away from them. With the further shift to post-industrialism and a yet more developed sense of self-actualization, which in turn propelled people toward greater wishes for social justice and diversity and new forms of individuality, further away from traditional status markers, all the stops have come off the rage and wish for retribution.

As for the elites, there are always such groups with a diminished sense of self lurking to exploit psychosocial vacuums to fill their desperation for power and advantage to feel worthy, and it is not entirely accidental that Trump’s favorite (only?) reading is Hitler’s speeches. The American constitution was designed to protect elites from factions, but factions per Madison of the poor and urban constituencies. As a result, there were no safeguards against an organized elite faction with a broad reach that could much more easily mobilize on a national level as they had precisely done with the Declaration, the Revolution, and the Constitution itself.

Richard Rorty, in accurately foreseeing a couple of decades ago in Achieving Our Country the cosmopolitan, meritocratic turn away from social justice and equality toward caste privilege just as a new hereditary caste elite of the “international super-rich” was seizing power and the left was disappearing, called on and called out progressives to reject the incendiary path of claiming an “America unforgiveable” and more so “unachievable.” I believe contrarily from more recent evidence that America as an early modern psychocultural and institutional achievement is not capable of taking the next step to new post-industrial forms of self-development and mutuality. This would require in Erich Fromm’s terms the cultivation of motivations of psychological abundance, selfhood, and internal empowerment rather than the incessant, unyielding drives of deficit and deficiency that fueled the liberal age. Too many, even progressives and radicals, have not yet come to terms with inward wholeness and empowerment (we thus, as Deresiewicz’s “excellent sheep,” have more but are less or not enough), to take on the power grab in the short run that seeks with total power to reinscribe absolute authority.

Plato saw as Thucydides that the logic of this system has an endpoint as tyranny consumes itself. The question for Plato and for theory (and all of us), however, is “what do we want instead?” As the contradictions and cleavages intensify, the disparity between the claims of this society that it fulfills appetites and the increasing wish for real gratification and authorship will become apparent. As the progressive and counterculture search for lasting and intrinsic fulfillment, for genuine meaning, self-worth, broke the liberal containment and appropriation of genuine libidinal possibility, a way forward will emerge: a new psychosocial and psycho-historical framework, such as that envisioned by Plato amidst the ruins of Thucydides’ Athens, a new ethos not like Plato’s proto-Christianity but based in a much different age on Rousseau’s distinction between a self-love that is abundant and genuine versus that vanity which arises from felt deficiency and the terrible hunger for (any) compensation to fill the hole at the center of one’s being.

The goal will be an authority constituted within oneself, in one’s own being, to flourish individually and collectivity while repelling aggrandizers and tempters and appropriators. This is the society gestating, the world that will emerge among the young, of the meritocracy, of the excluded, perhaps even of the plutocracy, who see in the paths of their parents and adult society lives of self-repression, self-abandonment, empty sorrow, hollow appetite, and power without meaning, who yearn for a world of self-embrace and care for others.

Those who foresee this new world are, then, not simply victims of the present scourge, but the instigators of the present civilizational crisis as a way toward making new dreams viable, who pulled out of a collapsing world view because of a more expansive humanity that could no longer fit, who recognize that this world will not emerge in the interstices and channels of the old (though born there), but in spaces where transformation is both possible and nurtured, where the ground has been cleared and prepared.

We and the generations that follow are thus makers of history, the seekers of a more realized world of possibilities that liberalism gave birth to but in the end could not provide. As I sat recently at an American soul and gospel concert on Christmas eve in Valencia, Spain, a capitol of the Spanish Republic, and saw local residents join hands in the transracial and transethnic dance of a new birth as reimagined by those from across the ocean, it struck me that the spirit released by American envisioning and the American promise, symbolized in the great movements and alternative cultures of the post-war era, will connect with others, republicans, indignados, anarchists, seekers, democrats, poets, who will come together in many places and many ways. Rome must come to an end – even if by the hand of its leader-executioners – that we all may move ahead. It is for us to create that path.