Hollywood’s African-American Films Since 2012

It seems such a long time ago since the “Beer Summit,” of 2009. When President Obama sat down with Harvard Professor Henry Louis Gates and Cambridge Police sergeant James Crowley. The Summit occurred after Crowley, had arrested Gates for breaking and entering his own home.

Although it was a minor though toxic incident, it appeared at a time when we had begun to fantasize that our racial divide might be simply resolved with some rational discourse and good will on each side.

However, in 2012 came the murder of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin by George Zimmerman, when even the President, who had long avoided calling attention to his own racial identity and issues, stated that Martin could have been his own son.

In many ways it was Martin’s death that first inspired a new generation of activists to take to the streets and protest against a system they felt held the lives of African Americans in small regard. In swift succession Martin’s killing was followed by the police killings of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri of Eric Garner in New York City, and the death of Freddie Gray in Baltimore in 2014. It led to a number of riots, and the rise of the “Black Lives Matter” movement, which demonstrated against the deaths of numerous other African Americans by police actions or while in police custody. In the summer of 2015, Black Lives Matter began to publicly challenge politicians to state their positions on BLM issues.

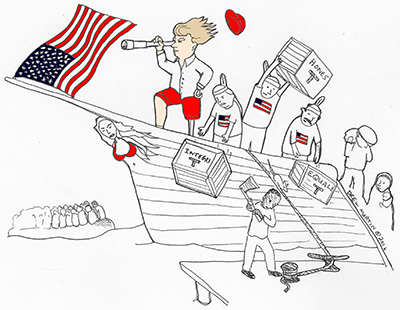

So it seemed that after all the complacent boasting of a post-racial society, that developed after the election of Barack Obama in 2008, America’s original sin and prime domestic problem was back in the forefront of our consciousness. It even included a proposed boycott of the 2016 Academy Awards by Black actors and directors, who were upset, because no African-Americans had been nominated for the leading awards.

There is an ironic aspect to this last incident, because awards aside, if one looks back on the period between 2012 and 2015, one sees a succession of films about the African –American experience that would certainly hold their own against mort of the best films produced in American cinema. The films include some that dealt historically with the African-American experience as well as others exploring issues of contemporary African–American life, including events that predated and might even have inspired the “Black Lives Matter” movement.

The first of these, and the most historically resonant, was the Academy Award winning 12 Years a Slave (2013), directed by Steve McQueen (Hunger, 2008, Shame, 2011). 12 Years a Slave was adapted from the 1853 memoir of the same title by Solomon Northup, a relatively prosperous freeman and violinist living in Saratoga Springs NY, who was kidnapped by slavers in Washington D.C and then sold South.

Through all the horrors he goes through, Northup (Chiwetel Ejiofor in a low-keyed, subtle performance), renamed Platt, survives. In a telling moment that is illustrative of what horrors slaves were confronted with, he and a couple of other slaves debate whether to resist or to acquiesce to their condition. Northrup chooses what he thinks will be temporary acquiescence. He would rather survive than fall into despair. For a fellow slave dying is better than being in servitude.

Platt is sold to William Ford (Benedict Cumberbatch). The ineffectually kind but hypocritical Ford believes he is good to his slaves because he reads scripture to them. However, he allows his vicious overseer Tibeats (Paul Dano) to torment them, chanting “run nigger run” while they work. Platt driven to the brink by Tibeats’ resentment and bullying strikes the overseer, and for this offense is hung from a tree with his toes barely touching the ground to prevent him from choking to death.

No scene evokes the historical powerlessness of the slaves in the face of absolute white power as this moment in the film. As Platt hangs from the tree, McQueen captures the other slaves on the plantation, fearing for their own lives, going about their business as usual, none of them, except one, even acknowledging Platt’s horrific predicament.

Finally, released Platt is sold to the volatile, alcoholic, God-invoking slave breaker Edwin Epps (Michael Fassbender). The brutal Epps works his slaves mercilessly, imposes crushing quotas of cotton, whips them for the slightest infraction, has them dance after a day’s labor for his own pleasure, and curses them out as ‘black dogs.” He even flaunts his sexual relationship with the beautiful slave Patsey (Lupita Nyong’o)–his “queen”– in front of his unhappy, enraged termagant of a wife (a powerful high-pitched performance from Sarah Paulson), who goads him to punish her. Patsey is so profoundly tormented by her fate as a sexual possession that she asks Platt to kill her—she sees it as a “merciful” act. Instead Platt is later coerced to lash her mercilessly turning her back into a bleeding sore when she defies Epps, forcing Platt to become a collaborator in the victimization of his own people.

After a number of futile attempts at contacting someone who might help him, Northrup, with the help of a sympathetic, anti-slavery contractor Bass (Brad Pitt), makes contact with people in Saratoga and is finally freed. Pitt, one of the film’s producers, gives himself that sympathetic role, and though he speechifies a bit about justice and righteousness, the film never loses its way, and becomes a polemic.The film’s stirring conclusion depicts Northup’s tear-filled reunion with his wife and by now fully grown children. In the aftermath of this, and what is not shown in the film, is Northrup’s later career as an abolitionist spokesman both in the United States and abroad.

Despite McQueen’s, who came out of the London gallery-and-museum world of short films and videos, tendency to compose stunning images in long shot, and shoot some scenes using striking chiaroscuro, 12 Years a Slave never seems too aestheticized. It neither romanticizes American slavery as Gone with the Wind (1939) in its creation of an ante-bellum plantation idyll does, or turns it into a source of eroticism as in Mandingo (1975). Instead we see the terror and savagery of a world where slaves are never seen as human beings, but as property to be used and abused by their masters according to their every whim and desire. Slavery in the film means men and women being sold like cattle, children, torn from their mothers, and men, women, and children laboring ceaselessly whose only reward was not being whipped. It is a world of white power and privilege built on the backs of slaves.

By centering the film on a respectable, caring, well-spoken freeman like Northup, a man who must hide both his personal history and the rage he feels towards an institution that dehumanizes him, the film forcefully conveys how there wasn’t anybody that was black, however advantaged (Northup had been ostensibly accepted in Saratoga, and knew whites who were willing to rescue him), that did not suffer the consequence of America’s horrendous racism. It permeated every aspect of the society. In long takes and penetrating tight close ups McQueen’s camera focuses on a despairing Northup, whose sorrow is overwhelming, but no more so than the millions of slaves that could not read and write, and would never taste freedom in their lives.

In a sense Lee Daniel’s (2013) begins where 12 Years a Slave ends. Cecil Gaines (Forest Whitaker) witnesses the rape of his mother (Mariah Carey) and the murder of his father (David Banner) by a drunken white plantation owner (Alex Pettyer). Touched with guilt the plantation owner’s mother (Vanessa Redgrave), who is a racist, takes in Cecil to work as a servant, initiating what would eventually become a three-decade career as a butler in the White House.

Cecil’s story was a adapted by Lee Daniels (Precious, 2009) and his scriptwriter Danny Strong from a 2008 Washington Post article by Will Hapgood about Eugene Allen, who worked for 30 years as a butler in the White House. Cecil is a stoical but perceptive observer of history as he alternately serves Presidents Dwight Eisenhower (Robin Williams), John F. Kennedy (James Marsden), Lyndon B. Johnson (Liev Schreiber), Richard Nixon (a profoundly uneasy and politically calculating John Cusack), and Ronald Reagan (Alan Rickman), a star-studded cast all performing generally on target cameos. It’s a breezy run through of the Presidents’ diverse personas and their relationship to the civil rights movement.

Cecil’s submissiveness—he almost never raises his voice– and commitment to playing it safe (he adheres to the dictum that a butler should be invisible) is vividly contrasted with the political activism of his estranged son Louis (David Oyelowo), by Daniels’ fluid crosscutting. Louis is alternately a participant in sit-ins, Freedom Rides, and even for a brief time becomes is a member of the Black Panthers–talking radical cant. Though he is turned off by their emphasis on guns and violence and leaves. While Cecil and the other black butlers mutely serve at formal, all-white dinners at the White House. Cecil’s chain-smoking, heavy-drinking wife Gloria, played with verve by Oprah Winfrey, also has a very different personality than Cecil’s. She is as expressive, and aggressive as Cecil is emotionally controlled and passive. Still, he is the apotheosis of decency. (He is even sufficiently affected by the civil rights movement that he drops being submissive for a moment, and asks his contemptuous white boss for equal pay and greater opportunities for the black staff.) When Nancy Reagan (Jane Fonda) invites Gloria and Cecil to a White House state dinner, Gloria is exhilarated, but the invitation, which Cecil sees as mainly “for show,” doesn’t have any effect on Ronald Reagan’s right wing policies. (Reagan still refused to vote sanctions against the apartheid regime in South Africa.)

The Butler is most incisive as a cinematic evocation of W.E.B Dubois’ seminal insight that African-Americans wore “two faces.” It also clearly illustrates the black poet Paul Dunbar’s lines that African-Americans of generations before the civil rights movement, “wear the mask that grins and lies.”

Otherwise, it’s a film that explicitly spells out its point of view, wearing its message on its sleeve. It never stops manipulating our emotions, even using a melancholy tinkling piano to underlie the scenes depicting Cecil and Gloria aging. Close to the film’s conclusion, Cecil has an epiphany, and begins to share his son’s political vision. He now sees him as a “hero” committed to saving the “soul of the country.” Daniels ends the film on a triumphant note, with Obama winning the Presidency–a result of the actions of Louis, and all the courageous, risk-taking activists that preceded him. The Butler can’t fail to move us–offering the audience an abridged and flattened historical pageant, with characters that can’t help elicit our sympathy. This is a shallow, obvious, conventional film that one can’t stop watching.

The masks that Cecil and the other butlers wore are non-existent in Ava Duvernay’s (I Will Follow, 2010) 2014 film Selma, which chronicles the struggle of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (David Oyelowo) to gain voting rights for African-Americans. Duvernay and her scriptwriter Paul Webb portray King as a visionary who is totally focused on gaining equality for his people. At the same time it portrays in much less detail his conflicts with his wife Coretta (Carmen Ejogo), who suspects him of infidelity, and his conflicts over political tactics with young radicals of SNCC such as James Foreman (Trai Byers) and John Lewis (Stephan James).

Duvernay avoids portraying King as a man free of self-doubt. One sees this most poignantly when late one evening King calls the singer Mahalia Jackson (Ledisi Young) and asks her to let him hear the voice of the Lord, and she sings him the gospel classic “Precious Lord Take My Hand.”

Nonetheless, King is also shown to be an astute political tactician, who has learned from previous defeats of the movement’s efforts that only white intransigence and violence can gain the movement the kind of media coverage (i.e. the brutal response of Alabama’s racist and demagogic governor, George Wallace) that will produce action on the part of the federal government. And he is also no slouch in standing toe to toe with President Lyndon B. Johnson (Tom Wilkerson), himself no stranger to shrewd political maneuver, to attain his goals. Ultimately, the terrible violence of “Bloody Sunday,” (March 7, 1965), when Alabama State Troopers attacked the marchers, and the sympathy it generated throughout the country, resulted in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1965.

In her commitment to the heroism of King and the black protest movement, Duvernay seemed to go overboard by diminishing the political significance of LBJ’s commitment to civil rights. He is shown as initially hostile to the efforts of King. However, many historians1 of the period have denied this. Indeed some of Johnson’s former aides2 have even argued that he encouraged King and they worked together to pass the Civil Rights Act.

Nevertheless, what the film most reminds us of is how charismatic and eloquent King could be. For legal reasons, DuVernay had to reimagine King’s oratory, but the soaring words still have King’s cadence and moral resonance. If they lose something in authenticity, their authority remains.

There is no denying the power of these historical recreations. What were equally potent and compelling were the films depicting aspects of contemporary African-American life–their problems, victories, and tragedies. Benh Zeitlin and Lucy Alibers indie Beasts of the Southern Wild (2012) carries a hint of the anthropological, but is also clearly influenced by the romanticism of Terence Malick. It is set in a fictional place in Louisiana called “the Bathtub.” The Bathtub is a swamp-ridden, barren-looking bayou neighborhood of black and white families living in ramshackle homes and beached wrecked boats, whose lives seemed to revolve mainly around heavy drinking and fishing. Their homes are squalid, and the neighborhood is filled with rubbish and dogs, chickens and pigs freely wandering about. The people live lives far removed from middle class norms and behavior. Still, they may be dirty, and living on the margins, but they adhere to a serious code of their own: “You don’t let anyone down who’s in trouble.” One also feels the sense of true community among them where race plays no role.

The film focuses on the lives of the too cutely named Hushpuppy (the precocious six year old non-professional, Quvenzhane Wallis, whose point of view and voice dominates the film) and her angry father Wink (the non-professional Dwight Henry). Wink is an irresponsible father. He feeds Hushpuppy a steady diet of chicken, leaves her alone to fend for herself for long stretches of time, hits and shouts at her, but despite it all one can see that there is a fierce love and attachment between them.

Hushpuppy who narrates some of the film is an almost magical child—a bit too self-consciously and pretentiously so. She mourns and fantasizes about the mother who deserted her, communes with the animals, talks about the universe, and has a rich imagination. The film includes magic realist scenes of ferocious primordial beasts called Aurochs who are dislodged from polar icecaps and drift down to wreck havoc on the Gulf Coast. The images may be too literal, but Hushpuppy conjures them up at times to make some sense of the darker aspects of her life.

The community is destroyed by a storm, and, despite protests, everyone is evacuated to a medical center where they are given clean clothes. After the death of Wink, who has heart problems, some of the inhabitants of the Bathtub including Hushpuppy throw off the new clothes given to them by aid workers and march over water proudly back home in a scene reminiscent of Soviet filmmakers choreographing Chekhov’s Three Sisters striding off to Moscow. In its final image, this quasi-fable embraces the indomitability of an impoverished, mixed race community; a lovely, utopian fantasy.

Equally fierce in their attachment to their culture and to their origins in South Central L.A. are the young Black men who became one of the first gangsta’ rap groups N.W.A (Niggaz Wit Attitude ) in Straight Outta Compton (2015) a film directed by F. Gary Gray (The Italian Job, 2003). Dr. Dre (Corey Hawkins), Ice Cube (O’Shea Jackson, Jr. , son of the real Ice Cube), D.J. Yella (Neil Bron Jr.) M.C. Ren (Aldis Hodge), Eazy-E (Jason Mitchell) make up the group after Easy E, tired of the constant danger of dealing drugs, decides to finance their venture into rap.

On one level the film is a rags to riches tale as the group burst onto the music scene from nowhere and is catapulted to fame and fortune including grand houses with pools where bikini-clad young women party with the rappers and their entourage. But it is also a cautionary tale of what big money can do, as the group begins to break apart as a result of squabbles with their shrewd, duplicitous manager, Jerry Heller (Paul Giamatti) around cash and contracts. For N.W.A. whose limited knowledge of the world is tied to the street ethos, and their obsession with money and fame, their absence of any business sense (they are easily preyed upon by anybody who can read a contract) begins to undermine their success.

But more importantly the film is about the social world–the street culture– out of which the group emerged. Or as Ice Cube put it, “Our art is a reflection of our reality.” And that reality is conveyed in the unfiltered rage and obscenity laced lyrics about volatile inner city life–guns, weed, cars, intimidating, vicious cops and toxic violence– that became the hallmark of West Coast Rap. (Much of that same self-destructive rage, but without the shaping of an artistic sensibility, determines some of their personal encounters.) Perhaps the moment in the film where that is most clear is when, after being warned not to, the group does its most famous rap “Fuck the Police,” and it causes, given the lyrics, a riot: “They have the authority to kill a minority

Fuck that shit, cause I ain’t the one

For a punk motherfucker with a badge and a gun”

As we write–police have killed more black men–and we can see how little has changed in that dynamic.

The film also depicts some of the seamier sides of the rap world. For example, hovering around the group, and doing his best to turn them against one another, is the thuggish, violent record producer Suge Knight (R. Marcus Taylor), who is surrounded by heavyweight enforcers. There is nothing redeeming about Suge. The group, and the film’s final moments coincide with the death of Easy E from AIDS–a result of his bad life choices, but also a genuinely forlorn and moving conclusion.

Nor does the film follow the lives and careers of the N.W.A. rappers after the group dissolved. So nothing is said about the most successful of the rappers, Ice Cube, who parlayed the group’s success into a career as an actor (Boyz in the Hood, 1991) and film producer (Barber Shop, 2004, and Ride Along, 2014). In addition there is no mention of Dr. Dre, who became a rap album producer, but was more noted for his brushes with the law, which resulted in a prison sentence in 1995. And while the other members of the group did not disappear into total obscurity their careers were hardly equivalent to their success with N.W.A. as D.J. Yella became a pornographer, and M.C. Ren turned from rap to the Sunni Moslem faith.

The reality of Black life that N.W.A. rapped about could have been a chorus’s comments on the life of Oscar Grant III (Michael Jordan). Grant was killed by a police officer January 1, 2009, and it was turned into a quietly powerful, realistic film closely based on the real story, Fruitvale Station (2013) directed by Ryan Coogler. The film begins with actual cell phone video from that fateful night.

Oscar is an ordinary man who at times can be sweet and kind, and is trying to be faithful to his often disappointed girlfriend (Melonie Diaz), dotes on their lively, smart little daughter (Ariana Neal), and attempts to be a good son to his strong, nurturing mother (Octavia Spencer). The director adds gratuitously to his virtues by having him sensitively comfort a dog after an accident. But try as he might Oscar has a hot-tempered, self-destructive and feckless side (he know he is a “fuck-up”). He is fired from his job working in a supermarket for constant lateness, and in order to pay his bills he deals drugs–an offense that he has already done some hard jail time for. But he suddenly decides to give up dealing drugs, and transform his life.

But on that fateful night Oscar is dissuaded from driving into downtown to celebrate New Years Eve, and instead ventures with friends and girl friend out on BART (Bay Area Rapid Transit). The trip, depicted by Coogler, is initially a festival of diversity, as white, black, and Hispanic, gay and straight, drinks, dance, sing, and celebrate on board the subway car. But when a fight breaks out, the police are called—they are viewed in the film as either brutal or dangerously inexperienced– which leads to Oscar’s angry and deadly confrontation with them.

In a hint of countless demonstrations to come, there were large-scale protests in Oakland over Oscar’s death. And eerily prefiguring the future: the police officer that shot Oscar was convicted of involuntary manslaughter because he claimed he thought he was shooting Oscar with a taser instead of a gun. Of course, he received a sentence of a little over a year, and was released in 11 months, typical of the minimal or non-existent punishments that were meted out to police in the killings that followed.

More than just a memorial to Oscar Grant III, Fruitvale Station is a stirring reminder of how often these kinds of scenes have been re-enacted in this country even before Ferguson, New York City, Baltimore, St. Paul, Baton Rouge and into the future. The film makes no explicit critique of the nature of American society. But the film strongly suggests that there are too many young black men with potential like Oscar’s adrift, and that there will be a long wait until we achieve a post-racial society. A modicum of economic and social justice and police restraint is all we can hope for.

These films one knows are just the first step of the many works that will follow focusing on both African-American history, and on the social and psychological reality of black life in present day America. Though there can be no expectation that films can in any way cure the ills of our society, they can dramatize the texture of black life–its strengths, imperfections, and clear, justifiable grievances. So, if we ever begin to believe we can make the kind of progress that makes race and racial issues a peripheral rather than primary problem (a color-blind society?); these films may make a difference. More importantly for African-Americans, the films may help them achieve what Professor Henry Louis Gates spoke of after the Beer Summit that, “If we take control of our own stories, we can take control of the narrative.”

Notes

- David Garrow, Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Morrow, 1986.

2.” ‘Selma’ Controversy Grows Over LBJ Clash with Martin Luther King on Civil Rights,” The Wrap, Alicia Brooks, January 2, 2015.