Kevin M. Kruse, One Nation Under God-How Corporate America Invented Christian America. New York: Basic Books, 2015.

How did conservative evangelical Christianity become the default religion of the US government, despite the legal separation of church and state? Kevin M. Kruse sees this as a Twentieth Century development, a process that started with the Eisenhower administration, continued through several others, and eventually solidified with the Reagan administration. The book offers impressive detail about the people, places, and events that united government with organized religion in general and conservative evangelicalism in particular. I don’t take issue with the evidence or with Kruse’s interpretation as far as it goes. However, he does leave the central thesis from the subtitle unresolved: how did corporate America invent Christian America? Indeed, I don’t think he addresses this question at all, either in the narrative or in the running discussion. Nevertheless, the book offers significant historical context and details about the activity of notable players, despite the imperceptible critical deliberation of their activities.

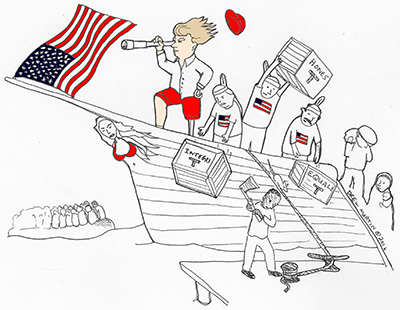

The historical narrative begins with the New Deal and moves quickly to post-war America, when the religious onslaught really begins. We see many leaders, all of them religious, fiercely patriotic, and often both. Among them, James Fifield and Abraham Verheide invoked the old-time religion of the previous century, but Billy Graham rose above the rest in religious ferocity, patriotism, right-wing politics, and with considerable political savvy, became a recurring character in the drama of American politics. Strangely absent, however, were corporate executives. While corporate leaders no doubt played a major role as well, they were apparently not directly involved with the religious side. In the absence of direct evidence, let’s consider the logic of such an alliance, if it did exist. Mentioned here and there, Kruse depicts ‘the corporation’ as a kind of malevolent Great Oz behind the curtain.

How would severe religious moralism and pro-war patriotism benefit this nebulous and fiendishly clever entity, the corporation? With the only intact industrial base in the post-war era (except for the Soviet Union), US capitalism embraced mass production consumerism in order to sustain the over-production of the war years. Instead of tanks, planes, and guns, industry cranked out ever new and improved cars, appliances, and all manner of objects to satisfy any desire both subtle and gross, and roads to connect the meccas of consumer indulgence and consumption—shopping malls and immersive simulations like Disney World. Consumerism only intensified over the next several decades. How does conservative evangelicalism support such indulgence? What would the nature of their alleged political alliance be?

The best that Kruse offers is speculative, that “Hollywood and Madison Avenue…helped promote this understanding of America as a religious nation and Americans as an inherently religious people” (p. 293). If Hollywood and Madison Avenue played such a decisive role, he doesn’t show this. If the corporate world deployed religion as some kind of market encouragement, how would this increase profits? Overwhelmingly, the book focuses on the cultural battles and political maneuvering of religious leaders and conservative politicians. The book offers no discussion or even awareness of class or capitalism. These mighty and mysterious things, the corporations, remain shadowy phantoms in Kruse’s mid-Twentieth century America.

A major figure throughout the book, Billy Graham’s hard-edged condemnation of sin, organized labor, and quest for a moral awakening embodies a particularly conservative evangelicalism that makes it compatible with conservative political agendas in some ways, but Graham and his ilk did not speak for all of the devout, especially those who later condemned American imperialism in Korea and Vietnam. Let’s also remember that the Civil Rights movement (which Graham strongly opposed) started in Black churches. Graham’s uniquely conservative and highly moralistic agenda brought him and his Washington Crusade to the capital in January 1952 in the closing months of the Truman administration.

The overt outcome of the rallies and lobbying led to Congress passing the National Day of Prayer, which bound Truman and all subsequent Presidents by law to call the nation to prayer. Less than enthusiastic, Truman spent the day watching a baseball double-header. Nevertheless, Kruse sees this as a decisive turning point. Although Graham insisted that he was non-partisan and would never reveal his political leanings, “he spent much of the 1952 campaign dropping what seemed to be considerable hints” (p. 61). He railed against communism and left-wingers, political corruption, and leftist religious leaders such as Reinhold Niebuhr who organized political opposition to Graham’s fusion of patriotism with the Gospel.

Based on the material that Kruse presents, conservative evangelicalism won many symbolic—rather than policy—victories in conjunction with President Eisenhower, who for example signed the Statement of Seven Divine Freedoms meant to demonstrate that “the United States of America had been founded on the principles of the Holy Bible” (p. 91). While this remained mostly a political touchstone for candidates claiming a “Christian” allegiance, the national pledge of allegiance became a much more public victory by officially inserting “under God” between “One nation” and “indivisible.” Eisenhower also approved the new one dollar bill which added the phrase “In God We Trust.”

In all of these symbolic outcomes, where is the corporate presence? How did the industrial capitalism of the period promote or benefit from conservative evangelicalism? Although Kruse mentions popular public figures (p. 160-161) such as Walt Disney and Cecile B. DeMille who used film to hint at (Disney) or openly promote (DeMille) Christianity, they behave more like Graham and other pastors—as religious entrepreneurs—not as corporate capitalists. DeMille’s big budget film The Bible and Disney’s simulations, like the pledge of allegiance and the innumerable campaigns of the period against sin and communism, like the Gideon’s placing Bibles in motel rooms (to which Catholics, among others, objected, because it was the King James version), are far more in the cultural realm than the economic.

The closest we get to actual capitalists with some direct public involvement with politics arrives years later with the Nixon administration, when the Mormons J. Willard Marriott (Hotel entrepreneur) and George Romney (CEO of American Motors) attended the inauguration ball (p. 247). Kruse is correct that decades of religious mobilizations and public displays of tacit political support made evangelicalism into a political force, but Marriott and Romney attended as individuals, not as representatives of their respective corporations. Halfway through the book, Kruse still has not shown that the ‘One Nation Under God’ colludes in some way with corporate America.

Far from a unified movement towards domination, Kruse’s narrative shows how the success of the early 1950s produced a backlash by the late Fifties that locked the two sides in battle throughout the Sixties and Seventies. Far from a decisive conservative triumph, Kruse shows instead how conservative religious activism divided the nation on many major issues, including race, gender, and sexuality.the late 1960s, the broad fusion of patriotism and piety “had become an important touchstone in an aggressive new conservatism” (p. 241). Billy Graham had fallen from favor under successive democratic administrations, but when Richard Nixon became President in 1968, he reinstated Billy Graham as the religious voice of America.

Although Nixon at least symbolically included Jewish, Catholic, and non-evangelical leaders in his religious celebrations (p. 245), the more conservative leaders held the greatest influence, and this reveals something of which Kruse seems unaware. While correct that conservative religious figures support(ed) the Republican party, Nixon, like his predecessors, restricted their influence to the symbolic realm and thus used their support for votes, but made only feeble if any attempts to enact any of their moral agenda. Just as he did in the early 1950s, and would again in the early 1980s when Reagan became President, Graham pontificated at the Nixon inauguration that “the religious pillars of our society have eroded in an increasingly materialistic and permissive society” (p. 246). Moral attacks on permissive indulgence, or indeed, anything that might reduce consumer spending is not what most corporate leaders want to hear. Moral entrepreneurs may bring in the votes, but Kruse can’t show that they ever really get a seat at the policy table.

For his part, Nixon added some more symbolic religious celebrations, including the National Prayer Breakfast and regular Sunday services. He let Billy Graham rave on about sin and the need for American redemption. He gave tacit support to Graham’s pro-America rallies and acknowledged the “Silent Majority” who allegedly supported the Vietnam war and prayer in public schools, opposed civil rights, inter-racial marriage, women’s rights, and environmental protection. Kruse notes donations from General Motors, Caterpillar, and Union Carbide among others, which seem in line with opposition to things like environmental regulation, but Kruse does not show that they supported the religious agenda in any way beyond their own economic interests.

For example, GM was one of the first major corporations to racially integrate its fabrication and assembly plants in the late 1950s, and the first industrial business of any kind to hire women engineers when Joan Klatil joined the Cadillac design studio in 1967. Granted, profit rather than social integration motivated GM, but as Marxists have realized since Marx, the inherent primacy of profit tends to minimize value systems grounded in religion or other traditions that inhibit the acquisition of profit. Class, not culture, eventually becomes the primary battleground. Kruse is clearly no Marxist. Neither is he a materialist or a social thinker; his narrative documents only the efforts and battles of individuals and their ideas in the transcendent realm of politics from where mandates flow once the deal-makers have concluded their business.

As a historical narrative, Kruse remains dedicated to the facts and offers only a bare-minimum running commentary. Consequently, we can interpret his extensive evidence ourselves, or simply file it away and bring out his book as a useful reference for something more critical and especially, for something more committed to class analysis. Kruse does not venture into conceptual discussions, much less any sort of theory, so we find very little basis of disagreement, but likewise very little basis of insight.

If corporate capitalism played any role in the rise of conservative evangelicalism or vise-versa, this book doesn’t show that. At all. Despite the legacy of overt piety and political affiliation that Kruse documents in great detail, the religious right has been remarkably unsuccessful in terms of actual policy. Today for example, we have national gay marriage, increasing legalization of marijuana, and very few young people make any attempt to avoid sexual activity until marriage.

The “Madison Avenue” advertising machine and the “Hollywood” cultural industry, the very champions of religious piety according to Kruse, in fact have and still market sensuality (revisit the steamy scenes back in 1945 between Bogey and Bacall—‘you know how to whistle dontcha Steve? You just put your lips together and blow’). Advertising has always tried to connect happiness with consumer consumption, not abstinence. Porn sites are the most popular on the internet, and they cater to every possible preference and fetish. If corporate America built and elevated conservative Christianity to political preeminence, where was (and is) the religious moral legislation? Kruse conflates symbolic displays of piety, of which there were and are many, with actual policy and legislation. Corporate America has invented ways to make profit from nearly everything, and if Kruse has shown anything, it would be that the political-economic system assimilated organized religion and turned it into another commodity, and in the process negated its power as an independent political force (but the reader must infer this as well).

Have the more secular democrats ever been any less beholden to corporate power? Were FDR and Truman less committed to big business than Eisenhower or Nixon? While some particular corporate owners and CEOs may at times express personal religious beliefs, this book does not show that a corporate-religious nexus has ever existed, nor that conservative religion ever wielded more than symbolic power. It gets out the votes, but the money is in secular profit, not in religious renewal or moral imposition. A better subtitle would be: How the religious right created and ultimately lost the culture wars.

George Lundskow is a professor at Grand Valley State University, Allendale, MI. He has published widely on the intersection of god, money, and power. For some of the people he studies, they are really the same thing. He dislikes disciplinary boundaries and embraces work from anyone that brings passion and insight to vital issues.