Poisoning the Well: Demagoguery versus Democracy

I am your voice.

Donald Trump, Republican National Convention, July 2016

Let us all hope that the dark clouds of racial prejudice will soon pass away and the deep fog of misunderstanding will be lifted from our fear drenched communities, and in some not too distant tomorrow the radiant stars of love and brotherhood will shine over our great nation with all their scintillating beauty.

Martin Luther King, Jr., “Letter From a Birmingham Jail”

Nearly all of us have been participants to informal, social conversations about contemporary politics or what’s commonly known as current events.

Whether with family or friends over a meal or with strangers in a bar or coffee shop, there’s always a sense of equality in these moments; everyone’s opinion has equal value and import. In part, this situation is magnified (and repeated) when others find out you teach government and politics for a living. The conversation often starts with the innocent, inquisitive “So, what do you think of the elections?”

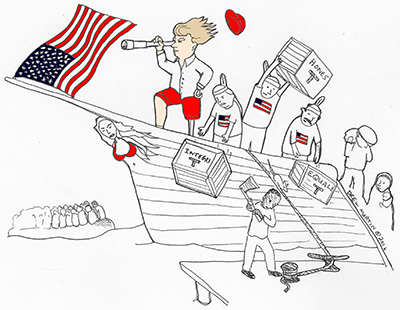

Our preferential tact is to turn the question back on the questioner, soliciting their analysis. In this election cycle the common refrain about Trump is a version of “He says the things that are on people’s mind. He says what lots of people think but don’t have the nerve to say.” When you probe further your (social) friends might try to fill in the blanks with “about immigration” or “about the rights of hard working Americans” or “about what’s wrong with this country.” [pullquote]Trump has tapped into a sentiment expressed as hatred of the political, and an existential fear that something is very wrong with America that only a singular “strong man” can rectify.[/pullquote]The response, often vague but indicative of a strongly felt sense of loss about something positively existential; about how things are not as they once were, how working people can’t achieve what they once could, how we’re no longer the great nation we once were, somehow lost at sea without a rudder. As Trump proclaims, he’s going to – personally – make America great again. And for this reason he is lauded.

Seemingly with each passing day Trump unleashes another racist, sexist, anti-Muslim, xenophobic comment; disparaging remark about the disabled or prisoners of war; a contradictory or incoherent policy statement; a veiled incitement to violence. The problem with these comments about the present state of affairs in America and how Trump says what is on “everyone’s mind” is that he does it. The people don’t. But the people also take no responsibility to illuminate or clarify what exactly is the problem and how it can be – democratically – remedied. Maybe there’s a reason why people who feel this way don’t feel any need to reasonably clarify their feelings; because we know they’re inconsiderate, selfish, privileged, marginalizing, exclusive, objectifying, dominating and deeply undemocratic. Trump is awarded for speaking like the bad child in the elementary school class. He alone speaks out of turn, caring little about the ramifications of his words. He says what others only wish they could say but thankfully, at least until now, know better than to be so brash.

As we have argued elsewhere, Trump capitalized on a conservative touchstone in the history of America – fear, disdain for established social, political and international norms, and the proposition that leadership through strength is the solution to the malaise created by ‘soft’ liberalism and political correctness.[1] Trump has tapped into a sentiment expressed as hatred of the political, and an existential fear that something is very wrong with America that only a singular “strong man” can rectify. It’s deeply undemocratic and speaks to a dangerous kernel of authoritarianism that lurks behind the veil of equality and liberty for all.

What emerges from this admiration for Trump as the one who speaks what’s on people’s mind is a voice conveying a passion for white ethnic nationalism, militaristic anti-Islamism, and appeals to bloodlust in foreign policy not to mention a desire to physically assault or incarcerate the political competition. These kinds of sentiments are not particular to Trump. Recall in the early days of the political season Trump was not alone in making public personal, bigoted statements. Both Ted Cruz and Ben Carson made such forays only to be outlasted by Trump who made such statements the centerpiece of his campaign. Despite occasional, tepid criticism of Trump’s comments by the standard bearers of the Republican Party House Speaker Paul Ryan, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, and Chair of the National Republican Committee Reince Priebus have stood by the Republican Presidential Nominee indicating the Republican establishment’s concurrence with the Trump vision.

What these candidates – or better the words they use in public – have managed to do is lower the bar on what might have always often been with us in the American political vocabulary and thoughts, a xenophobic and racist desire to scapegoat racial minorities and non-white immigrants. Hardship, whether it be real or perceived stokes racial as well as nativist resentment among underemployed, low wage, and middle-class whites whose economic position has eroded over the past forty years. The symptoms are real. Concern is with the perceived source of the problem and the proposed, nearly insane solutions such as a border wall with Mexico, trade wars, recusal of judges due to ethnic or religious bias, mass deportation, incarcerating the opposition, physically threatening those who dare criticize the nominee.

For many on the right, equality is synonymous with white oppression, politics synonymous with corruption and thoughtfulness synonymous with weakness. Donald Trump is not the first candidate to draw on these resentments among whites. Patrick Buchanan in his presidential runs in the 1990s did as well, framing whites’ economic insecurity as the product of racial equality, immigration, and economic internationalism. A passion for someone who says “what’s on people’s minds” in this instance is troubling because it obscures an understanding of the real culprit of economic hardship for whites, blacks, and Hispanics, namely, market fundamentalism. Market fundamentalism is economic system and accompanying ethic in which the maximization of profit and accumulation of wealth by corporations and investors is hegemonic. The power of corporations and wealthy individuals to manipulate the political and economic system to their corporate bottom line is the source of American workers’ predicament. It is undeniable that manufacturing employment in the US has been decimated. Undocumented immigrants have a large presence in our agriculture, food processing, landscaping, food service, and construction industries. The average American sees this when he or she unpacks his/her brand new electronic device and notices it is made in China. Or, when driving along the interstate and noticing Latino (documented or undocumented) agricultural workers picking the vegetables that end up at our dinner table. The average American’s immediate reaction may be that Latino workers and “the Chinese” are responsible for underemployment, stagnant wages, and increased economic insecurity. What this average American does not see are the massive profits of agribusinesses or tech companies, all of whom in the interest of maximizing profit margins have made the conscious decision not to employ the American workforce, insure dignified working conditions, and pay respectable wages. Trump himself boasts about these profit preoccupied employer decisions by hiring foreign guest workers at his resort and manufacturing his own ties in China. And this man proclaims as he accepts the Republican Party’s nomination for President of the United States, “I am your voice”? The insatiable pursuit of profit and wealth accumulation rests upon a compliant or confused political system that conflates results for causes and redirects people’s legitimate anger toward those least responsible for their condition.

In July 2016 Newt Gingrich can say in a CNN interview about national trends in crime and FBI violent crime data (what Gingrich refers to as theoretical facts) that, “as a political candidate I will go with how people feel and I’ll let you go with the theoreticians.” [2] That he would choose campaigning on feelings versus campaigning on facts (suggesting that feeling are facts) makes it easy to see how people’s economic condition can be supplanted by feelings rather than viewed through the lens of policy analysis and political discourse.

Public policy has exacerbated the upward transfer of wealth, the power of capital over labor, and the resultant economic crisis afflicting the vast majority of Americans. Both Trump and Bernie Sanders acknowledge this condition and empathetically spoke to these aggrieved Americans, hence Trump’s belief that Sanders’ voters will flock to him in the general election. Sanders’ analysis correctly placed the blame for the current economic state of affairs on powerful economic actors (corporations and the wealthy) and their friends in government. Tellingly, Sanders’ robust populist campaign was actively sabotaged by the Democratic Party. [3] Whereas, Donald Trump’s vague, dystopian diagnosis was legitimated by the GOP who refused to challenge him and by the circus-like media coverage his campaign received.[4] For those most acutely hurt by this unprecedented shift in wealth and power in America the political discourse has been framed, broadcast, and reified in cultural terms as the feeling that America is not what it once was. As vague and general as this sounds it is the dominant narrative that trickles down from the political class to the public discourse, then repeated as the new reality.

And so where does this leave us as educators who live for enlightened public discourse, a desire to continuously learn how to relearn what we know, to build on what’s good and make it better, to balance a passion for politics with a sense of the fragility of the status quo, an understanding of history and the dangers of demagoguery inherent in our democratic system? How do we as professionals dedicated to balance, reason, and teaching people how to think, speak, and behave politically confront this moment in history? Just how do we respond to such hatred, fear, passion and short sightedness?

To be sure, what we cannot do is to ignore divisive, hateful speech and hope that it is only a temporary manifestation and that it will go away if/when Trump is defeated. Nor can we retreat from it deriding such talk as frustratingly irrational, racist, xenophobic, etc. and so justifying our disengagement from the conversation. Democracy requires a commitment to rational discourse and to a public philosophy informed by the notion that the people need to know how to govern and be governed. To return to our hypothetical but common conversation with which we began the essay engagement prioritizing the principle of rationale, factually based public discourse constitutes the core of the democratic project. Such conversations might contribute to a greater understanding about America, so that, as King aptly states, “…the deep fog of misunderstanding will be lifted from our fear drenched communities” and we might, as educators, point the way towards an informed and civil democratic discourse.

Notes

[1] James E. Freeman and Peter Kolozi, “Trumpism is Conservatism: The New Conservative Mainstream,” Logos 15.1 (Winter, 2016), https://logosog.chrismordadev.com/2016/freeman_kolozi/

[2] Alisyn Camerota’s interview with Newt Gingrich at the RNC. See, “Feelings vs. Fact-Newt Gingrich-RNC Topic on Violent Crime-Feelings trump FBI Stats!”, youtube.com, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xnhJWusyj4I (published July 27, 2016)

[3] Marquita Peters, “Leaked Democratic Party Emails Show Members Tried to Undercut Sanders,” NPR (July 23, 2016), https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2016/07/23/487179496/leaked-democratic-party-emails-show-members-tried-to-undercut-sanders.

[4] On a comparison of media coverage of presidential primary candidates see Harvard study, Thomas E. Patterson, “Pre-Primary News Coverage of the 2016 Presidential Race: Trump’s Rise, Sanders’ Emergence, Clinton’s Struggles,” Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy (June 13, 2016), https://shorensteincenter.org/pre-primary-news-coverage-2016-trump-clinton-sanders/