John Matisonn, God, Spies and Lies: Finding South Africa’s Future Through its Past. Vlaeberg: Missing Ink, 2015.

South Africa seldom reaches news headlines nor are its politics a topic of much public concern elsewhere anymore. It has, in a certain sense, fallen into benign neglect. Internationally, the anti-apartheid sympathy for the Mandela administration extended itself right up to the current political regime, giving current president Jacob Zuma an unearned reprieve from scrutiny. John Matisson, a veteran South African journalist, here sifts expertly through the last 40 years of local journalism. What he turns up is a dismaying story of a long struggle to expose the inequities of racial segregation and apartheid, first basking in the enlightened free press during a short period after the democratization in 1994 and then a sorrier tale of relinquishing those same gains to Zuma’s more authoritarian style of regime.

The author, a well-known National Public Radio contributor and former Washington correspondent for a South African newspaper, draws on considerable personal experience, especially his long contacts with many major players. In addition, he provides evidence from confidential documents and more obscure published sources. The book covers far more than the decade preceding democratization and the decades after. The title itself, “Gods, Spies and Lies”, suggests his explanatory intertwining of religion, secrecy and intrigue.

The first section deals with the long early period from 1800 to 1966 where Matisonn sets the stage here for the rest of the critical narrative. From the early 19th century onward a crucial divide split the white population of the Cape. The conservative sections rejected racial equality and eventually rejected British rule too to found their own republics to the North. This rift only widened and hardened after the British colonizers defeated the republics in the Boer War. The humiliation and suffering of war fueled an intense national consciousness among the Dutch-descended Afrikaners, which eventually led to their victory at the polls where they unseated the United Party, a coalition of Afrikaans and English speakers. This dominant new National Party would remain in power until the democratic turnaround in 1994.

Afrikaner Calvinism based itself on the narrow interpretations of the Dutch theologian, and later statesman, Abraham Kuyper. He advanced the notion of the pillarization in society, meaning that separate religious and cultural orientations in a society are justified and sanctified to rule as sovereign entities. This extremely convenient form of self-legitimation underlay the apartheid system and the political mobilization of Afrikaners. The Afrikaner Broederbond (Pact of Brothers), comprising male elites, took on the self-imposed mission of building the solidarity of the Afrikaner people while at the same time countering any opposition by liberals and integrationists. Newspapers and media were important instruments for this suppressive purpose. English language newspapers were clearly on the other side of the divide and Matisonn gives us an insider view of how the liberal press dealt with the twisted arguments of their opponents as well as providing a voice for the excluded majority of Africans.

In the 1960’s nationalism triumphed across many African states. Other states were involved in struggles, with rebels often supported by the Soviet Union. This caused great consternation among Afrikaners who now, by way of their media mouthpieces, denounced African nationalism as entirely inspired and controlled by foreign Communism. The English language press came under the most intimidating suspicion. This was South Africa’s own little McCarthyism episode. Matisonn discloses how The Daily Mail and The Sunday Times struggled to exercise whatever freedom of expression they could manage under the energetic censorship of a paranoid, racist system. Mattisonn cites Charles Bloomberg’s contributions to unraveling the historical and ideological underpinnings of Apartheid. Bloomberg got hold of crucial Broederbond documents, which were then published in The Sunday Times. The “treachery” of the Afrikaner theologian, Geyser, who handed over the documents, was indicative of fault lines in the Afrikaner fold. Similarly, among English speakers there were turncoats like Craig Williamson, who spied on his colleagues.

In the second section, “Slugging it Out”, Matisonn covers the period during which the country’s cordon sanitaire, comprising Mozambique, Angola, South West Africa (now Namibia) and Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) came under attack by nationalist forces and, with their transformation into independent states, ultimately crumbled. The South African government believed the country was under both external and internal attack. Internally, these attacks happened not only by way of sabotage but also ideologically through a hostile and disloyal press. The governing forces therefore clandestinely funded startup of an English language newspaper, The Citizen, to counter what it deemed to be anti-government propaganda by the mainstream English press. Matisonn relates, tongue in the cheek, how this maneuver backfired and let to the downfall of major political figures, including the president J.B. Vorster.

Revealing also are personal encounters with actors such as the editor Percy Qoboza and the photographer Peter Magubane who played crucial roles in the development of media in the African population during the awakening of political consciousness among the youth. This was the era of Steve Biko and the Black Consciousness Movement, the Soweto student uprising and its bloody suppression. The political turmoil and violence of the aftermath of the Soweto received wide international attention – and Matisonn’s own contribution was substantial to consciousness-raising in America. Public outrage put the U.S. policies of constructive engagement with South Africa under such pressure that they had to be abandoned. The writing was on the wall for apartheid. The ongoing war in neighboring territories became too expensive and fruitless, international support evaporated, sanctions were biting hard and the economy was declining. President P.W. Botha started to drop certain apartheid laws and delegations of liberal whites including the author, business people and academics started meeting with the African National Congress (ANC), the leading liberation movement, outside the country in order to discuss the return of the exiled political movements and to plan the road ahead.

The third part of the book discusses the years of transformation between 1994 and 1996. This was the period preceded by the hammering out of a new constitution by the new body, the Convention of a Democratic South Africa (Codesa). The ANC’s insistence on ‘one person, one vote’ triumphed over the whites’ demand for the enshrinement of group rights. Codesa paved the way for the first democratic election in April 1994. Matisonn soon was asked to direct the South African Broadcasting Corporation’s (SABC) election coverage for 23 radio stations. The SABC was, up to now, the official mouthpiece of the government and was set for an uneasy transformation in the new democratic age. The election put the ANC under Mandela solidly in power. The economic transformation and redistribution plans were formulated in the Reconstruction and Development Plan. This document was deemed to be “unrealistic” in IMF terms and was superseded by the Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) program under Mandela’s successor, Thabo Mbeki. In the meantime Archbishop Desmond Tutu launched the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC).

The last section is perhaps the most interesting one to readers concerned with what happened since democratization. It is the period of both raised hopes and many frustrations as Matisonn himself experienced. It is a very detailed section that examines the euphoria of the first years as it gradually curdled into a sense of chaotic decline among the public. One trajectory Matisonn was closely involved with was the Independent Broadcasting Authority (IBA) created in 1993 “to promote greater diversity and historically disadvantaged ownership and content on radio and TV.” (p. 316) At first the IBA jealously guarded its independence. Gradually it eroded as councilors started accepting gifts in return of favors. Matisonn made himself very unpopular among councilors due to his opposition to corruption and he ultimately left.

One major scandal followed the other. There was a huge arms deal, the collapse of the educational system and more. A noteworthy chapter is devoted to foreign relations revealing South Africa’s pre-invasion relationship Iraq. South Africa had expertise in its own disarmament of weapons of mass destruction, nuclear and chemical. At the beginning of 2003 it played an active role in confirming Iraq’s disarmament. However, the USA planned its Iraq invasion against all evidence to the contrary. Mbeki and Mandela repeatedly notified the Bush administration of the non-existence of WMDs in Iraq. Mandela tried to reach Bush personally but was fobbed off. He remarked in front of cameras: “President Bush doesn’t know how to think.” (p. 360)

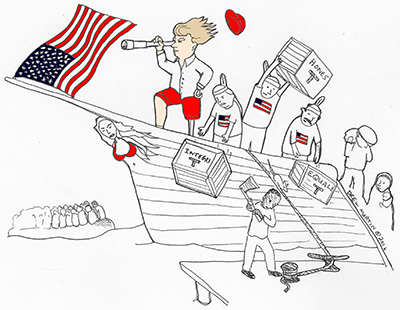

Jacob Zuma ascended to the presidency in 2007, inheriting a host of intrigues, corruption and monopolizations and turning them all to serve his personal agenda. The SABC degenerated into a pure government medium, suppressing opposition again. In the past it turned a small profit, now it had a thirteen-figure debt. Since publication of this book a Broadcasting Amendment Bill was placed before parliament. Its intent was to reduce a public broadcaster to a state broadcaster. This year the Chief operating Officer of the SABC Hlaudi Motsoeneng introduced pro-government censorship that spurred the resignation of a number of board members. The wheel seems to have made a complete spin, backwards to the apartheid era. However, there is still fierce opposition to these tendencies. Matisonn concludes: “For a brief, shining moment, we thought we had harnessed history, and perhaps we had. But history is an unruly mount. …..A new generation must embrace its challenge. They inherited a constitution that makes it possible. It’s up to them to find the will.” (p. 329) The new generation are the “born-free”, born after 1994. The challenge of facing up to despotic forces bent on destroying the constitution is indeed formidable.

From an analytical point of view he documents the struggles for control of the public sphere. In the early years the English language press made a valiant effort to pry open the closed system of information of the religiously legitimated establishment. In the 1960’s the hermetically sealed Afrikaner establishment showed cracks. A refreshing, inclusive liberal dialogue across racial borders ensued. It then became eclipsed by the anti-Communist, ‘black peril’ discourse and virtually froze during the violence of the 1980’s. Yet the foundations for an inclusive public sphere were laid in this period and blossomed in the early years of the new democracy. The interest of the emerging class of privileged cadre politicians soon darkened the transparency and accountability of political power. The extension and preservation of the public sphere is one key to deter the country from sliding towards a failed state.

In conclusion, this is a thoroughly readable and worthwhile work from the perspective of an engaged journalist. The writer of this review is a contemporary of Matisonn who grew up at the same time and the same area, though on the other side of the political divide as an Afrikaans speaker. My advantage in reading the book was a substantial prior knowledge and first hand exposure to events. For the not so initiated the narrative is sometimes jumpy and the chronology may be difficult to follow.

Gerhard Schutte taught Anthropology and Sociology at the University of the Witwatersrand until 1986 when he emigrated to the US. His research interests include comparative racial and ethnic relations.