Stuart Jeffries. Grand Hotel Abyss: The Lives of the Frankfurt School (London: Verso, 2016)

In Hail, Caesar! the Coen Brother’s recent paean to 1950s Hollywood, there is a curiously political scene in a later part of the film: Baird Whitlock (George Clooney) a popular cinematic heartthrob is kidnapped by a group of disgruntled (and secretly communist) screenwriters. Having hidden him in a well-appointed beach-front property, the kidnappers add insult to injury when they force the leading-man to attend their interminably boring Marxist discussion group. Initially confused, Baird Whitlock falls under the spell of the circle’s philosophical guru, a vaguely mitteleuropäische academic named Prof. Marcuse and is soon speaking a leftist lingo, spouting talk of “theories generating their own anti-theories”. For those in the know, “Prof. Marcuse” was a recognizable figure, a barely concealed remake of Herbert Marcuse, the radical German-Jewish social theorist. And Marcuse’s densely-worded philosophy is accorded a similar status as the sword-and-sandal epics and camp musicals pastiched in Hail, Caesar!; all are cultural artifacts from a distant past. For sure they are presented with a fairly gentle nostalgia. But it is a nostalgia that reinforces how old-fashioned this all is for twenty-first-century viewers. Densely Hegelian Marxist philosophy is a lot like technicolor cinema; they don’t make them like that any more.

Stuart Jeffries’ wonderfully readable group biography of the Frankfurt School (of which Prof. Marcuse was only one of several key theorists) politely disagrees; the critical theory of Marcuse, Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer and, more recently, Jürgen Habermas has great relevance for our hyper-mediatized and profoundly unequal world.

The Frankfurt School, officially the Institut für Sozialforschung [Institute for Social Research], emerged out of a sense of disillusionment after the collapse of the Spartacist Revolution of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht. The founding members were gripped by a sense of despair; the question of why proletarians, rather than seeking revolution, instead seem content with their own oppression would continue to animate their philosophical writings. The Institute was initially devoted to a fairly orthodox Marxism, with the work of the economist Henryk Grossman and Carl Grünberg, a historian and Director of the Institute, to the fore. At this early stage, Jeffries points out the odd incongruities that defined the Frankfurt School; heavily Marxist but with an anodyne name that would allow them to escape too much scrutiny from the authorities or from their hosts at the University of Frankfurt; suspicious of the far-right and capitalist modernity in equal measure, but housed in a custom-built modernist building designed by an architect who would later develop Nazi sympathies; anti-capitalist but bankrolled by Hermann Weil, the wealthy father of their official founder, Felix Weil. Indeed, as Jeffries regularly points out, the majority of the charter members of the School had remarkably similar backgrounds: Jewish sons of wealthy fathers who rejected their bourgeois heritage, but still took their monetary inheritances.

In 1931, Max Horkheimer took over the Institute’s directorship and soon signaled a radical change in the Frankfurt School’s work. The emphasis on a strictly economistic conception of Marxism was abandoned, in favor of a focus on popular culture and an admixture of Freudianism. The centrality of Labour in Orthodox Marxism was abandoned for a new focus on consumerism. Horkheimer had already been going in this direction in his work, as had the classical musician-turned-philosopher, Theodor Adorno. Under Horkheimer, the Institute went interdisciplinary; “The Frankfurt School… decided to remove the white gloves… and get its hand dirty. It would study horoscopes, movies, jazz, sexual repression, sadomasochism, the disgusting manifestations of unconscious sexual impulses, take critical notes at the trough of mass culture, and explore the shabby metaphysical foundations in the basements of rival philosophies.”

The rise of Nazism and the continuing concern of why large fractions of the German working class sought salvation through their own oppression, were obvious impetuses here. For the Frankfurt School, Nazi oppression was of a piece with the general oppressiveness of life under Capitalism. But what would come to be called Critical Theory was not just a response to a specific moment of genuine political crisis; it was an attempt to synthesize a diverse array of influences. As Jeffries points out, the posthumous publication of Marx’s Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844 – more humanistic than his later economic writings – also played a part. As did the work of György Lukács – whose History and Class Consciousness helped introduce themes of alienation and reification into the Frankfurt School’s work – and Walter Benjamin, who had long had informal connections with the School and whose musings on life under capitalism and on a haute-bourgeois German-Jewish childhood resonated with his comrades. Jeffries lingers for quite a while on Benjamin; he becomes almost a central character in this group biography, despite never being an official member of the Institute for Social Research. There is a similar pause to take in Lukács’ ideas. The narrative is languorous and meandering, but not tiring or self-indulgent. This is a history that capably takes in many of the Frankfurt School’s diverse tributaries.

The other major shift occurring under Horkheimer’s direction was the relocation of the School out of Germany. Even before the Nazi seizure of power, a branch of the Institute had been set up in Geneva. After 1933, the entire Frankfurt School left Germany, managing to find an institutional home in Columbia University. In some ways, the arrival in Morningside Heights did little to change the School. Their intellectual combativeness remained intact, as did their view about the essential similarities of capitalism and Nazism, a position that was even less tenable in FDR’s America and which the author rightly pinpricks; in general, Jeffries wisely pushes against the polemical flourishes of Adorno et al whilst salvaging the many valuable parts of their analyses.

When Adorno moved to Los Angeles in 1941 he became even more dyspeptic about American culture. He was appalled by Hollywood even as leading figures in the city’s arts and entertainment community embraced him. Adorno played piano at parties in Charlie Chaplin’s house by night, and excoriated American popular culture by day. In one particular reflection, Adorno compared this new country’s commercialized music to “the sound of dropping dog food in a bowl”. Such thinking was channeled into the more sober investigations of Dialectic of Enlightenment, a study of modernity and the roots of Nazism co-written with Horkheimer, and one of the most important works of all the School’s output. Other members of the School were less detached during their American sojourn. Herbert Marcuse found employment interpreting German society for the Office of Strategic Services, precursor to the CIA, an anti-Fascist action he would later be called on to explain when he became a mentor of the counter-culture.

Toward the end of the War, Adorno completed his study of The Authoritarian Personality, a sociological investigation of the political temperaments of 2,099 participants. Unsurprisingly, he saw authoritarian tendencies as ever-present in the USA. It was a grim parting gift for his hosts; in 1949, the year before The Authoritarian Personality was published, Adorno left America to take up a position back at the University of Frankfurt.this time, his hopes for a future socialist revolution were non-existent. Horkheimer, who also returned to Germany, had reached a similar set of conclusions. Their work studied the repressive nature of capitalism whilst foregoing the possibility of escaping capitalism. They were now far removed, Jeffries points out, from Marx’s famous view in his Theses on Feuerbach, that “The philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point, however, is to change it.” Perhaps most shockingly, Adorno was becoming a respectable academic.

Conversely, Marcuse stayed on in America, eventually teaching at Columbia, Harvard, and Brandeis, and remained less pessimistic about the future and less domesticated. He also attained a certain amount of late-career popular appeal, first with his 1955 work Eros and Civilization, later with One-Dimensional Man, a favorite among student radicals. The widening gap between Adorno and Marcuse is neatly highlighted by Marcuse’s shock when he heard, in 1968, that his old colleague had gone so far as to call the police on students occupying the buildings of the Institut für Sozialforschung. For Adorno, the 68ers were dangerously authoritarian, for Marcuse they were potential allies. (Though Marcuse was less conciliatory when students led by Daniel Cohn-Bendit protested one of his own talks during a visit to Rome that year).

The savants of the Frankfurt School ranged across sociology and philosophy, economics and popular culture, sexuality and political science. The complexity and diversity of their writings are intensified by an infamously inaccessible style. When a young Angela Davis went to Frankfurt in the early 1960s as an exchange student, she presumed her difficulties understanding Adorno’s lectures were due to a lack of proficiency in German; her German classmates soon told her they found Adorno equally incomprehensible. Stuart Jeffries does a remarkable job condensing and explaining the School’s collective output, though some might feel his compression misses out on some of their nuances and complexities. He weaves their works into a compelling narrative that still leaves room for amusing sidebars (two highlights being the bizarre James Bond-esque Soviet spy, Richard Sorge, who ingratiated himself with the Frankfurt School in the 1920s, and Max Horkheimer’s awful teenage novels).

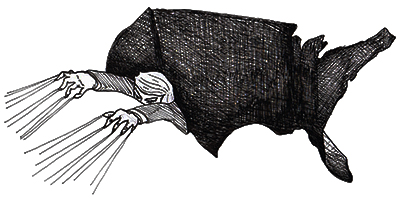

Jeffries ends this book making a strong case for the importance of Adorno, Marcuse and Co. to contemporary discussions of authoritarianism, consumer culture, and the penetration of capitalism down into the deepest crevices of society. Reification, the projecting of autonomy and human characteristics onto commodities and commercial relations, a recurring trope for the Frankfurt School, is certainly a relevant idea for understanding the commodity fetishism of late capitalism, for understanding iPhones, Hipsterdom’s veneration of faux-artisanal products, and a social media that encourages us all to become our own consumer brands. Herbert Marcuse’s qualified skepticism about the chances of social revolution seem almost tailor-made for a world in which anger is rife and yet supposedly There Is No Alternative. And the recent course of American politics only bears out the importance of Adorno’s emphases on authoritarianism (indeed in December The New Yorker ran with the headline “The Frankfurt School Knew Trump Was Coming”). Grand Hotel Abyss might just be a creepily relevant book for 2017.

Aidan Beatty is Scholar-in-Residence at the School of Canadian Irish Studies Concordia University, Montreal and is author of Masculinities and Power in Irish Nationalism,1884-1938.