The Life and Times of the Underground Press — Part 2: Art and Design

Books reviewed:

Power to the People: The Graphic Design of the Radical Press and the Rise of the Counter-Culture, 1964-1974, edited by Geoff Kaplan.

Full Circle: The Life & Works of Karl-Heinz Meschbach, written by Karen Black.

BUSTED!

It was late 1968, after the protests and repression around the Democratic Convention. KOed by asthma, I looked forward to diving into the pages of The Chicago Seed—the underground newspaper I edited—when my then-girlfriend, the eponymous “Mary Sunshine,” brought the latest issue home. The Seed was one of hundreds of radical / counter-cultural periodicals of the 1960s and early 1970s. As Karen Black, the biographer of one of The Seed’s best artists, puts it:

Articles on the latest “far-out” musicians appeared next to mantras about

rights and equality for Blacks, Women and Native Americans…prison life, abortion and draft-dodging.[1]

A highlight of this particular Seed was a typically meticulous pen-and-ink spread—“Memories”—containing scores of images by Black’s subject, Karl-Heinz Meschbach. Karl’s finely detailed cornucopia included “Thou Shalt Not Kill” and soldiers with rifles, Jesus and “Hope,” a local DJ and a Chicago cop. If you looked hard, a headshot of Mayor Daley sat just below an image of, well, someone giving head.

Karl wasn’t arrested, but two paper sellers and I were, for obscenity. One count of the indictment had me being “reckless in my editorial responsibility.” Charges eventually were dropped but not without a verbal slap from the judge: “The Seed was “trashy, but not obscene.”

We ran the arbiter’s quote on the masthead. But Karl, who’d trained as a Certified Decorative Painter, had the last word, in an open letter:

I demand that my work be judged solely on the basis of artistic merit…

I am willing to defend my work in any time in any place to intelligent

people….[2]

Most every underground paper had an encounter like this one, because they deliberately pushed the envelope, or because the authorities wanted to repress their dissident politics or cultural expressiveness. Whichever it was, design was key to their message. The papers’ visual presence varied far more than that of typical mass-circulation dailies. The Seed wasn’t as “Tibetan Book of the Dead” as The San Francisco Oracle, with that paper’s swirls and third eyes,[3] but it used far more graphics than photos and illuminated them through a split-fountain press process that allowed colors to flow into each other. While legibility could succumb to production glitches, realistic and metaphysical images alike flowed through their pages.

In contrast, The Berkeley Barb was an enraged inkblot, with black-and-white photos augmenting street-fighting dispatches. New York’s East Village Other (EVO) probably was the biggest exponent of underground comix, hipster-themed panels that substituted The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers for Dick Tracy. Boston’s Avatar and the San Francisco Good Times were crisp; others barely rose above the mimeograph level even as they got the word out.

To date, most accounts of underground press graphics have centered on the comix of R. Crumb, Gilbert Shelton and other celebrated cartoonists.[4] Now, two profusely illustrated books—a strong overview of the papers and a loving tale of one artist’s evolution—enrich the literature.

IMAGES AND ESSAYS

Power to the People: The Graphic Design of the Radical Press and the Rise of the Counter-Culture, 1964-1974 notes how technology from margin-justifying typewriters to cheap offset printing presaged today’s Internet disruption. To this end, Power starts with a found document: “How to Make a Magazine,” rescued from the lesbian magazine Amazon Quarterly as a template for organizing through media. Today it’s at once primitive and redolent of endless hours spent around a light table forging “news from below.”

Power’s editor, Cal Arts design professor Geoff Kaplan, cites the papers’ “…do-it-yourself ethos, their fervent belief in freedom of expression and their staunch advocacy of both a politically radical and countercultural lifestyle.”[5] Their design fueled “…a vehement challenge to the dominance of official media and a critical form of self-representation.”[6]

Power is oversized, and its meat consists of hundreds of well-reproduced illustrations. Though dates are noted, the collective arc is non-sequential, stressing energy rather than evolution. Perspective comes from several incisive essays, which themselves are offset by colorful yet highly legible typography.

This combination makes Power to the People a worthy successor to a 2006 collection, Free Press: Underground & Alternative Publications 1965-1975.[7] Free Press, also oversized, carries striking images and author Jean-Francois Bizot drew on his time as founder of the French undergrounder Actuel to annotate issues into a lively concluding timeline that is missing in Power. But Power’s imagery is more comprehensive, and it explores corollaries such as The Whole Earth Catalog (early Wikipedia in print) and video collectives.

Power could use more recollections of artists conjuring up images to capture the latest street clash or psychedelic journey, more snapshots of the layout nights that East Village Other veteran Steven Heller elsewhere described as “the closest thing I had ever come to a tribal ritual”[8]

But Power’s essays, though sometimes slipping into sociologese, do add a thoughtful layer to the work. Speaking about the Oracle, San Francisco State art history professor Gwen Allen cites an article by uber-Beat William Burroughs extolling LSD, laid out with circles, mandalas and distorted columns—truth in packaging, indeed. Allen’s larger point: “…these alternative papers did not report on reality but sought to transform it.[9] The montages published in underground papers were not seamless, but announced their constructed nature through uneven, torn edges and jarring contrasts in scale and perspective. They registered a sense of crisis, of rupture and conflict, of things breaking apart.[10]

Clenched fists and images of cops as pigs “defined shared struggles and common enemies,”[11] Allen notes. However, Allen admits that sexist and racist images not only offended “conventional social codes” but were “walking an exceedingly thin line between lampooning stereotypes and perpetuating them.”[12] This led to internecine conflict, especially over how women were represented. One person’s sexual liberation could be another’s sexism.

The general appraisal is warts-and-all positive, as summarized by author / musician / UC Davis professor of technocultural studies Bob Ostertag:

“created shattered under the combined weight of state repression, sectarian politics and too much drug use. But if instead of looking at flags and governments, we look at real-life human relationships, a quite different picture comes into view. Nearly every type of human relationship emerged from the era profoundly changed, and in every case the change was toward greater equality.[13]

Ostertag then goes all-in:

Measured by how real people live real lives, the 1960s can be considered the most successful revolution ever, certainly far more successful than those revolutions that succeeded in seizing the reins of state power.[14]

And these ideas “…were first introduced to the world in the pages of the colorful, zany joyous, tripped-out pages of the underground press.”[15]

ART AFTER THE REVOLUTION

Power to the People covers papers that largely ceased fire nearly 40 years ago. For every artist who kept his (most were men) Rapidograph pens honed, several became mainstream or commercial designers, or simply left their craft behind. Comix artists seemed most likely to stay the course, but even the archetypal R. Crumb recently illustrated a faithful version of the Book of Genesis.[16] Steven Heller has authored scores of books and is an expert on typography and graphic design at The School of Visual Arts after a long career at The New York Times Book Review.

Karl-Heinz Meschbach continues to create evocative art.

A frequent Seed freelancer, Karl’s background differed from most others at the paper. While we were rebelling against middle-class conformity and U.S. interventions, Karl’s drawings were informed by secret-police interrogation in his native East Germany, a stint in a refugee camp and being penniless not by choice. He’d later served in the U.S. Army, as a gunner—ironically in (West) Germany. This wasn’t necessarily predictive—the biggest “freak” at The Seed had spent time in a displaced person’s camp in Italy—but, perhaps ironically in light of “the bust,” Karl’s work avoided trendy beliefs. As Black notes, “…in many of his [early] works, there is a lone figure musing about the world.”[17]

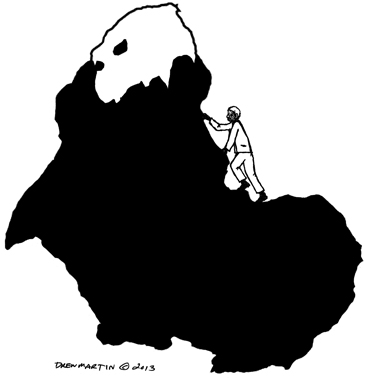

Black, herself a painter, characterizes Karl’s work as “some earthy, some ethereal.”[18] Even drawings of chained Black Panther leader Bobby Seale circa the Chicago Seven trial and the Statue of Liberty as a crowned skull convey an elegant sensibility. But as the paper’s politics moved toward hyper-militancy Karl, like others, headed for the exit. “Having escaped Communism, Karl had absolutely no tolerance nor understanding for that ilk,”[19] Black writes. The paper became more internationalist, with more talk of revolutionary violence. The art became coarser.

Being in The Seed launched Karl into the larger society, but Full Circle goes far beyond his relatively brief radical-press period to trace the evolution of a talented artist. Black’s oversized book depicts Karl’s move toward oils and an array of female nudes, gatherings of men, landscapes, abstracts, flowers—most marked by the lushest of color palettes. Karl’s work receded from public view, then gained national attention with a burst of decorative murals for homes. Walls and ceilings became his canvas, trompe l’oeil a specialty. Now he lectures internationally and continues to paint—“skyscapes” are one recent subject.

In 2010, Karl made the first of what have become several working and teaching visits to Berlin. There he received an Honorary Master Certificate from the Berlin Master Painter School. He has, indeed, come “full circle.”

Notes

[1] Black, Karen, writer, Full Circle: The Life & Works of Karl-Heinz Meschbach, Studio K Galleries, 2012, page 31.

[2] Black, ibid.

[3] Oracle editor Allen Cohen anthologized a facsimile edition of the paper in 1990 and a CD-ROM “digital re-creation” in 2005. A posthumous paperback appeared in 2011 (Global Recording Artists).

[4] In addition to works by individual underground artists, overviews specific to underground comix include: Estren, Mark James, A History of Underground Comics: 20th Anniversary Edition, Ronin, 2012; Kitchen, Dennis, and Danky, James, Underground Classics: The Transformation of Comics into Comix, Abrams 2009; Rosenkranz, Patrick, Rebel Visions: The Underground Comix Revolution, Fantagraphics, 2008; Skinn, Dez, Comix: The Underground Revolution, Thunder’s Mouth, 2004.

[5] Kaplan, Geoff, editor, Power to the People: The Graphic Design of the Radical Press and the Rise of the Counter-Culture, 1964-1974, University of Chicago, 2013, page 6.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Jean-Francois Bizot, Free Press: Underground & Alternative Publications 1965-1975,

Universe, 2006.

[8] Heller, Steven, Steven Heller’s Dada, The Local East Village, January 15, 2012.

[9] Ibid, Gwen Allen, page 81.

[10] Ibid, page 101.

[11] Ibid, page 111.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid, Bob Ostertag, page 197.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Crumb, Robert, The Book of Genesis, W. W. Norton, 2009.

[17] Black, page 27.

[18] Ibid, page 49.

[19] Ibid, page 35.

————–

Abe Peck is a professor emeritus in service and senior director of the Media Management Center at the Medill School of Journalism, Northwestern University. He is the author of Uncovering the Sixties: The Life and Times of the Underground Press, edited The Chicago Seed underground newspaper and was on the steering committee of the Underground Press Syndicate during the 1960s. He edited Dancing Madness and co-edited Medill on Media Engagement, worked at Rolling Stone, Outside, The Chicago Sun-Times and The Chicago Daily News, has written for numerous publications and consults on media worldwide.