On Creationism and Our Dark Politics: One Hundred Years After the Scopes Trial

May 25th marked the hundredth anniversary of the Scopes Trial. On that day in 1925, a Tennessee science teacher, John Scopes, was indicted and convicted for teaching evolution. Recognizing that the issues that gave rise to the Trial remain stridently relevant today, I want to use this centenary occasion to take a deeper look.

The Scopes Trial was in great measure a battle between “East Coast elites” and the rural sectors of the American populace that has long considered itself under the thumb of the privileged classes. The conflict between Darwinism and creationism was a conflict of ideas and the content of the science curriculum in public schools. But it was much more than that. It was a cultural conflict writ large, encompassing issues of religion, economic class, social status, and prestige, and who controls education. It reminds us that the divisions we now painfully witness have long defined American society.

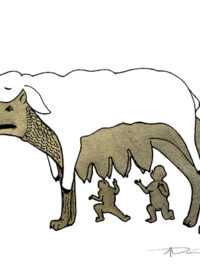

The Scopes Trial, which brought William Jennings Bryan to Dayton to prosecute the case, and Clarence Darrow, recruited by the American Civil Liberties Union, to serve as Scopes’s defense attorney, attracted widespread national attention. Though Scopes lost, the evangelicals suffered embarrassment so great that they retreated from the political arena, not to reemerge until the Moral Majority came onto the scene in the late 1970s.

Historian Heather Cox Richardson, in a recent Substack newsletter, marks that retreat. But she also notes that a strategy adopted by fundamentalists post-Scopes was to try to transform business in ways that aligned with their Christianity. They came to see the New Deal and the move toward social welfare as hostile to religion. The foundations for free enterprise, individualism, anti-Enlightenment, and anti-intellectualism, grew stronger. With Christian nationalism today on the march, and fundamentalists being a mainstay of the MAGA movement, the forces that intensified in the wake of the Scopes Trial are reaching a feverish pitch. The alliance between ultra-conservative religion and politics has become dark and ominous.

According to a Gallup poll conducted last year, 37% of all Americans believe God created the first human beings less than 10,000 years ago, a belief that is the intellectual equivalent of contending that the earth is flat. Not more than 24% of Americans believe in the natural evolution of the human species absent any divine intervention. Interestingly, despite the stridency expressed by politicized fundamentalists, the numbers espousing pure creationism have grown smaller in the past few decades and those affirming an unalloyed Darwinism have risen. This seemingly counter-intuitive finding may result from the fact that those who attend church regularly tend to affirm creationism in greater numbers, and there has been a large drop in church affiliation in recent decades.

Creationism may not be the most salient issue of our times, but it assuredly is an iconic one. Embedded in it is a value system that stands in defiance of the Enlightenment, embraces anti-intellectualism, gives no credence to science, and more broadly ignores the rules of evidence. It holds in disregard the assertions of learned authority. The conflict between evolution and creationism exemplifies the breach between modernity and the religion-fueled zeitgeist of earlier and darker times of human history. Its assertion is emblematic of the cultural and political demands that so fretfully are tearing American society asunder.

In light of the anniversary of the Scopes Trial, I want to take a deeper look at creationism and its claims. I want to briefly examine why creationism wins wide assent while evolution continues to fall on such hard times in the popular mind, and its place within a broader range of issues.

First, at the risk of sounding dogmatic, there is no alternative to the theory of evolution in the scientific community. Since Darwin published his Origin of Species in 1859, the brilliant idea that all species, including our own, evolve by the process of natural selection, stands as a pillar of biology, as fundamental to science as the heliocentric theory or the germ theory of disease. Whatever debate there is, and there is plenty of debate, takes place within the theory of evolution, not between evolution and alternative explanations of how species came to be. Indeed, it is a strategy of anti-Darwinists to paint the internal debate within the biological community over the nuances of evolution as a weakness, when, in fact, it is a strength of the theory of evolution, as it is of all robust science. As Ian Hacking, a philosopher of science has noted, the theory of evolution has gone “from strength to strength.” He says that the theory of evolution “constantly reacts to counterexamples and difficulties by producing new theories that overcome old hurdles. When challenged it does not withdraw into some safe corner but explains new difficulties with an even riskier, richer, and bolder story about nature.” In other words, any science is not a static body of knowledge, but a dynamic process, that continually grows through overcoming internal problems. Though the basic principles that Darwin laid down 166 years ago endure, they have been refined, nuanced, and expanded so that the theory of evolution rests on even firmer ground today than it did then. In brief terms, the theory of evolution itself is evolving.

In the face of the attacks of the anti-Darwinists, (and they come in several different forms) the most common response of the scientific community is not to answer them on their own terms, but essentially dismiss and refute creationism as not being a science, but simply as gussied up religion, and as such not worthy of a scientific response.

In the 1970s and 80s, in the wake of their failure to eliminate the teaching of evolution from the schools, those who favored a biblical version of the origin of the species did two things. They gave the Genesis stories of creation the trapping of a science, which they referred to as “creationism” or “scientific creationism,” and eliminated all references to God, Jesus, or Satan. They also built institutes such as the Institute for Creation Research, in San Diego, to give their cause the patina of respectability and to further their cause and increase their financial base. Most importantly, they developed a fallback strategy. Rather than bar the teaching of evolution from the public schools, they demanded equal time for the teaching of “creation science” appealing to the notion that education would be best served by exposing students to all sides of the issue, again, suggesting that the jury was still out on the legitimacy of the Darwinian theory of evolution. After all, what could be more appealing than allowing creationism in the schools on the basis of “fairness,” or “equal time,” or “permitting all sides of the debate to be heard?”

This initiative was tested in the courts in the 1980s after Louisiana and Arkansas passed laws permitting creationism to be taught in their public schools. To its credit, the court, including the US Supreme Court, in what was sometimes referred to as Scopes II, unmasked creationism for what it is, namely an effort to bring religion into the schools by clothing it with the language of science. Expert witnesses, including the famed paleontologist, Stephen J. Gould, testified that creationism fails to meet the test of science. Among other things, science in order to be science must be amenable to change when it is confronted by new evidence. Creationism, by contrast, is insulated from the scientific method, because its notion of the special creation of fixed “kinds” is simply a given, which is not amenable to change based on evidence. In other words, it is a religious doctrine and whatever it is, it is not science, and as such has no place in a science classroom.

My point here, again, is to show that the prevailing way in which the scientific community has dealt with creationism is to discard it as not being science, and therefore beyond consideration as a science. It is religion and not science, and therefore outside the reach, interest, or even competence of science to consider. In other words, it is simply irrelevant. Science has its realm; religion has its own realm. Science answers questions dealing with facts and how the world works. Religion deals with metaphysical speculations and morals, and why things are the way they are, not how. Science has nothing substantive to say about religion; religion should keep its hands off of science. Since creationism is really religion, not science at all, the scientific community should ignore it, and its specious claims.

Because this opinion is so widespread, I was particularly intrigued when I found a book that takes a different approach. Living With Darwin, by Columbia University philosophy professor, Philip Kitcher, has been broadly and favorably reviewed.

Kitcher’s approach is rather than dismiss creationism on the grounds that it is not a science, he concludes that creationism is “a failed science.” Creationism, of some sort, actually has a long pedigree. It was not born with the Moral Majority in the late 70s. Nor, did it emerge right before the Scopes Trial in 1925, nor with the birth of modern fundamentalism in the early decades of the twentieth century. What is not apparent to most critics of creationism is that prior to the advent of Darwinism in the late 1850s, special creation was the normative theory of the origin of species held by the scientific community. What these naturalists, mostly British and Americans, held was that each species of plant and animal was fixed and that God either brought new species into being through an act of miraculous intervention, or through some law of nature that was not understood, but reflected God’s will and his purpose. Among those who held to special creation were the scientific luminaries of the day, including the British geologist Charles Lyell, who provided the proof for the great antiquity of geological forms, and thus laid the groundwork for Darwinian evolution, and Louis Agassiz of Harvard, who was the most important natural scientist in America before the advent of Darwinism. As Agassiz once said, “There runs throughout Nature unmistakable evidence of thought.” What he meant by thought was divine thought; God’s thought and God’s will.

It should be noted that Darwin, whose theory does not require indwelling thought, divine or otherwise, but asserts that the evolution of species is explicable by blind natural forces alone, understood very well what was at stake in his biological theorizing. Though he was not a theologian, Darwin realized profoundly the revolutionary effect that his Origin of Species would have on religion, which I will discuss later.

When Agassiz speculated that nature reveals divine thought and purpose, he was expressing a very powerful impulse in both nineteenth-century science and religion. In briefest terms, it can be said, that the prestige of science among educated people was at its high water mark in the nineteenth century. As such religious thinkers would look to science itself in order to strengthen and confirm their religious beliefs and claims. Most powerful was what was known as “natural theology.” It was the belief that the natural world confirmed the existence of a purposeful God and that a belief in such a God, was therefore warranted.

The centerpiece of natural theology was the so-called “argument from design,” which has experienced a rebirth in the work of contemporary creationists who now espouse the doctrine of Intelligent Design, as the latest attempt to get God into the schools.

The premiere theologian of the natural design argument was an English Protestant, William Paley, who in 1802, put forward his tremendously influential and well-known theorem, which has come to be known as the “watchmaker argument.” Paley tells us that if you are sauntering on the beach, and come across a pebble or a rock, you can well conclude that its formation is the product of the natural forces of erosion. But – you come across a watch, with all its interlocking moving parts, and you can only conclude that it is the creation of an intelligent, purposeful designer in the form of a watchmaker. By simple analogy, the watch is to the watchmaker, as the world is to a Cosmic Designer, a Creator God. If we look at the human eye, isn’t it clear that it is exquisitely designed? In all its minute, harmoniously working parts isn’t it made for the purpose of seeing? The implications of this argument are far-reaching. The world and us in it are created for a purpose. And since God is the Creator, his purpose is not only to guide the world, but it is also benevolent.

Paley created a cottage industry of natural theologians, who comfortably overlooked the fact that there was nothing Christian about the Watchmaker God. He didn’t even have to be omnipotent. Any god simply powerful enough to create the world would do. Even polytheism, with many gods, would satisfy the argument from design,

What Darwin did, of course, was to radically destroy natural theology and this kind of reasoning. The eye was not purposely designed for seeing, but evolved slowly over eons from crude photo-sensitive cells, as species struggled to survive and to adapt, and as mutations accidentally fitted certain individuals with light-sensitive receptors which enhanced their survivability. Purpose, divine or otherwise, had nothing to do with it. It is blind nature all the way down. Indeed, it is the theory of natural selection that lays bare that nature, in the struggle for survival, is immensely destructive and wasteful, and given the suffering of innumerable sentient creatures, unspeakably cruel as well.

I mention this history, to point to the fact that creationism is nothing new, and in fact has a long, and at one time, respected pedigree. Creationism in its current form has gone through three stages, which Kitcher, in his book, argues has been thoroughly discredited. I will go through the arguments very briefly.

The first type of creationists has been called “Genesis creationists,” or, “young earth,” creationists. These are the ones who contend that the earth is no more than 10,000 years old, and who hold literally to the creation story as it appears in the book of Genesis. A big question that confronts these literalists is how to account for the fossil record. The answer is simple they say: fossils were created in the recession of the waters of Noah’s flood.

The fossil record does appear in strata of rocks with the earliest organisms at the bottom and the more recent ones in the upper layers of the rock formations. Superficially this might seem to comport with the Genesis story. We do find the fossils of fish, for the most part, at the lower strata, and birds always at the top. Genesis creationists have argued that this confirms their theory: As the waters of the flood receded, fish were entombed early, whereas birds flew away, and were entombed later near the top strata. The problem is in the details. Dolphins, which are mammals, occupy the same habitats as fish, yet dolphins are always found in the top strata of the fossil areas, while sharks, which are fish are at the bottom. When we look at the fossil record of birds, according to the arguments of creationists, we should expect to find flightless birds, like ostriches and penguins at the bottom strata with the fish, yet flightless birds, like all birds are found in the upper layers, just as evolution would have it.

Kitcher’s conclusions, when we take creationism at its word, as a science, beyond conceptualizing how Noah would have gotten millions of species onto his ark, and kept predators away from prey, dismally fails on the basis of the more sober evidence, as this small example reveals.

Having lost that scientific battle, creationists had generally given up the “young earth” hypothesis and moved on to what is known as “novelty creationism.” What this affirms is that natural selection can perhaps explain variations within species, but it cannot explain macroevolution, that is major transitions from fish to reptiles, or reptiles to birds or to mammals. For these major transitions, there needs to be a special intervention, an act of special creation, and we can conclude that this pertains to the creation of the human species as well. In so doing, such novelty creationists deny that the living world is one seamless organic whole, a complex, interconnected tree of life, which was the illustrative metaphor that Darwin himself employed.

The novelty creationists have adopted the strategy that a good defense is a strong offense. They point to weaknesses in the theory of evolution, making the claim that if species evolve from earlier ones, then we should be able to find in the fossil record the remains of transitional species, which we do not. This absence in the fossil record troubled Darwin himself. Yet, the novelty creationists are wrong.

Paleontologists have indeed found fossils of such transitional species, the most famous one being the archaeopteryx, which is intermediate between reptiles and birds. They have found many fossilized remains of so-called therapsids, that is, species transitional between reptiles and mammals. As suggested earlier, there are examples in the contemporary natural world of different stages of the development of the eye in different species, moving from simple photosensitive cells that can merely discriminate between light and darkness, all the way to the complex eyes of mammals and birds.

Having failed the test of evidence on that score, the creationists have pulled out their last card; by resurrecting the argument of Intelligent Design. The claim here, briefly stated, is that organisms in some instances, especially on the molecular level, are so complex, that natural processes alone are simply not adequate to explain them.

In the 1990s, Intelligent Design theorists found a champion in Michael Behe a professor of biochemistry at Lafayette University, who has written several texts criticizing the alleged inadequacy of Darwinian selection.

Looking at the flagella of bacteria, the tiny motors that enable some species of bacteria to move, Behe argues that they are so irreducibly complex that all the biochemical components need to be in place simultaneously for the flagella to work, and that natural selection that produces random mutations one at a time, can not accomplish this. Only by resorting to an Intelligent Designer can we explain the complexity of the bacterial flagella.

Behe has thrown up some interesting challenges for evolutionists. Many have been able to answer these challenges in terms of the theory of evolution. But even if all his questions have not been fully answered, there are certainly fallacies in his reasoning. Just because the answers to his questions are not currently, fully known, it doesn’t mean that they are unknowable. Perhaps more importantly, by invoking an Intelligent Designer as the cause of what he claims is irreducible complexity, Behe has told us nothing that adds to our understanding. Indeed, Darwin has shown us that merely because a system looks as if it is designed, doesn’t mean that it is. Furthermore, by making the claims that certain organisms are the product of an Intelligent Designer, such creationists have told us nothing about the mechanisms by which this designer works. Therefore, the claim is scientifically useless.

The summit of public notoriety of Intelligent Design theory was reached in 2005, in a landmark court case in Dover Pennsylvania, wherein the deciding judge, John Jones, in a tightly argued opinion, concluded that Intelligent Design is not science. He concluded that it is “the progeny of creationism” and the latest effort to get religion taught in the public schools, and as such unconstitutional.

But we need to ask, despite 160 years of solid science, why is the commitment to anti-Darwinism so broadly and so deeply held in the minds of most Americans? There are many reasons, and, as I bring this survey to a close, I would like to proffer a few.

The first has to do with the frightful poverty of science teaching, and more broadly, an appreciation for critical thinking skills.

It’s my belief, however, that this is not enough to account for this broad-based and lasting phenomenon. More far-reaching is that Darwinism in its pure form, more powerfully than any science robs human beings of a providential God who cares for them, assures that they have a place in the universe, and, therefore, their life has meaning. This reality is a tough pill for human beings to swallow. It is a harsh blow to the human ego, to one’s deep-rooted feelings of security, and to the fears occasioned by the harshness and the vicissitudes of life, tragedy, and death. Most people don’t want those anchorages taken away from them. But if one takes the implications of Darwin seriously, it becomes very difficult, if not impossible, to retain these anchorages.

But even these deep-rooted, existential dynamics, are, of themselves, sufficient to explain the broad rejection of Darwinism in American life. After all, our European cousins look at the creationist phenomenon with incredulity and bewilderment.

I think there is a third reason, specific to American culture. My eyes were opened to this explanation when I read the historian Garry Wills’ description of the Scopes trial and what was at stake in it. It appears in his book on American politics and religion entitled Under God. The play and movie, Inherit the Wind about the Scopes trial in 1925, as noted, pitted William Jennings Bryan, the once Secretary of State and three-time presidential candidate, against the great agnostic from Chicago, the most acclaimed defense attorney of his day, Clarence Darrow. At the trial, Darrow called Bryan to the stand to defend the truth of the Book of Genesis. In the press of his day, as in the play and movie, Bryan was depicted as a narrow-minded fundamentalist and a fool.

But in truth, Bryan was not at all a fool and he was not even a strict biblical literalist. He was a progressive political fighter, who was also a populist, whose concern was defending the rights and integrity of the powerless. And as Wills makes clear, what was going on in Bryan’s mind in Dayton, Tennessee, was not primarily a fight against the biological theory of evolution. It was foremost a battle against social Darwinism, that much-touted philosophy of the rich and powerful, which perverted Darwinism into a social theory that claimed that “the survival of the fittest” (a term that Darwin himself never used) ensured that nature itself dictated that those who were rich and powerful deserved to be so, and those got the short end of the stick, those who lost out in the economic struggle which was part and parcel of the capitalist system, the poor, powerless, and disadvantaged, also got exactly what they deserved. As the wealthy and privileged heard the gospel of social Darwinism preached in their churches, the poor retreated to their churches where they found consolation in the old-time religion which was deeply ingrained in their cultural identities. And so it has remained.

Anti-Darwinism does not have much of an audience in the large cities of America, and it has little following in the Northeast. Where it does flourish is in the rural outbacks of the South, the Midwest, and the Rocky Mountain states. And the reasons for this flourishing, I believe, most of all, are multi-cultural reasons. From the perspective of those outside the Washington-Boston axis and the West Coast, those areas, especially the Northeast, are the locus of federal power, of Wall Street, of those who own the corporations and the factories, the publishing interests, the dominant cultural expressions, and the educational norms which set the way of life for everyone else. In brief terms, the anti-Darwinian movement is a political movement; it is a populist political protest against the dominant power centers of America. It is a protest against elitism, against know-it-allism, against the pretensions of intellectualism and its perceived condescension. It is an expression, in the truest sense, of the culture war, which uses religion as a weapon to fight that war.

As I am attempting to convey, the persistence of creationism has roots that are far deeper and more extensive than the issue itself. Where the future lies, no one can predict. In the narrow sense, I think the forces of enlightenment are winning this battle. Darwinism has been vindicated in the arena of science. But as we have painfully come to learn, this victory will be built on a shallow foundation unless broader economic and social conditions start moving in a more promising direction. In briefest terms, I don’t believe that the erosion of the middle class, an immoral wealth gap, growing economic malaise, and substandard education speak well for an enlightened, rational, populace that will joyously embrace the truths of science, and its glories, evolution included.

In closing, with regard to religion, I believe it is very difficult, indeed virtually impossible to give credence to Darwinism and accept the traditional notion of a supernatural God who cares for us and will ensure that everything will turn out for the best in the end. In the face of Darwinism, religion needs either yield to secularism or be transformed in ways that can accommodate the revelations of empirical science. The traditional religions now reflect two basic tendencies. There are those that are hardening. They have become more rigid, parochial, and fundamentalist. In ways that deny traditional understandings of religious faith, the evangelical churches have become primarily reactionary political organizations rallying their followers by condemnation of those of liberal persuasion. By contrast, the mainline Protestant churches and the liberal Jewish denominations, under the pressures of modernity and science, have liberalized and placed themselves greatly in accord with the values of the Enlightenment. It is these religious denominations that are experiencing the greatest loss of affiliation.

The Chinese adage that “we are bleeding from a thousand wounds” aptly describes our times. Our nation was founded on several principles that have defined it for 250 years. Central to our democracy has been a system of checks and balances. Having broken free of monarchy that the founders held in contempt, and fearing the centralization of power, the founders created a system of divided authority, which Trump is rapidly destroying.

The United States was created at an era when wars of religion, sustained by state power, had drenched European soil with the deaths of countless Catholics and Protestants. Beyond the American experience, religion sustained by the state has been the breeding ground for the darkest expressions of authoritarianism. History witnessed this in Franco’s Spain, in Argentina’s “dirty war,” in Putin’s Russia, in the early decades in Russia under the czars, and in much of the Islamic world.

Keeping religion and government separate has been a mainstay of freedom. It is a bulwark of liberal government. But under the pressure of Christian conservatives, the wall of separation is being torn apart brick by brick. Ominously, we have a Supreme Court that is increasingly sympathetic to this tragic turn. The denial of evolution is apiece with Trump’s assault on knowledge, education, science, and democracy. It takes its place with a list of other incursions of religion into the public square, inclusive of bringing prayer back into the schools, using tax money to support religious education, and denying health benefits that offend the religious doctrines of employers. No doubt this list will expand.

We witness now the ugly forces of Christian nationalism. It’s a grossly intolerant, reactionary, movement in the vanguard of Trump’s despotic destruction of liberal democracy. It seeks to establish the United States as a Christian nation and make fundamentalist doctrine the law of the land, imposed on believers and non-believers alike.

It is a hundred years since the Scopes Trial, and the extraordinary success of science, conjoined with the achievements of modernity, has not vanquished the forces of ignorance. Despite its failings, we who have lived through the decades of post-war America have enjoyed the gifts of liberty, knowledge, and the promise of a more bountiful and just future. We need to struggle however we must to ensure that the light not be extinguished.