Thinking Protests in Iran

Forty-four years ago, the image of an Iranian woman, dressed in the traditional Shiite chador and holding a G-3 automatic rifle, had become one of the hallmarks of the Iranian revolution of 1979. Today, the key iconic image of the protests in Iran, which has being going on for four months, since the death in custody of Mahsa (Jina) Amini, a 22-year-old Kurdish Iranian woman, on September 16, is that of a young woman burning her headscarf and chanting against the Iranian clerics. For the past sixteen weeks, people around the world have been witnessing scenes of nation-wide revolts around Iran, confronted by an unprecedented cruelty and violence of the Iranian security forces and the paramilitary militia (the Basij). According to some human rights organizations outside Iran, at least 459 protesters have been killed by Iranian security forces since the beginning of the urban revolts. including 64 minors. Also, despite the efforts of many Iranian and non-Iranian activists around the world and the symbolic sanctions implemented by countries like Canada, the UK and the European Council, there has been no real negative effect on Iranian officials. Nearly 16,000 individuals, including journalists, academics, artists, sportsmen, feminists, filmmakers, and students have been arrested and tortured by Iranian Revolutionary Guards, while the death toll of protestors is rising every day and the mass trials of those in jail because of the recent events are fast approaching.

Let us not forget that state violence and mass executions have been going on in the Islamic Republic of Iran for the past four decades. As such, the Iranian regime has responded with violence, election frauds, lies, corruption, imprisonment, and murder to all the economic, social and political demands of Iranian citizens. For forty-four years, many social categories of the Iranian population, especially women, have been trying to get back their personal lives, which were destroyed by the Iranian revolution in 1979. Yet, despite the rule of the political theology in Iran and the divine concept of sovereignty, which is derived from God’s will through the medium of Shi’i institutions of an Imamate and bestowed on the existing faqih (today Ayatollah Ali Khamenei) as the rightful ruler of the Shi’ite community, dissent and urban riots have been a common feature of the social and political life in Iran. From the demonstrations of the Iranian women against mandatory veiling on March 8, 1979, less than a month after the taking of power by Ayatollah Khomeini and the Iranian Islamists, to the students protests of 1999, the Green Movement of 2009 against the fraudulent re-election of Mahmood Ahmadinejad, and more recently the 2017 and 2018 urban protests which spread to 140 cities around Iran, practically every five years or even less, Iran has been the scene of a series of social movements, urban demonstrations and nonviolent activism, which were encountered by violent government crackdowns.

Yet, the key question to ask would be: if the young and middle-class population of Iran has repeatedly opposed the clerical regime in Iran, why are we in a position to say that with the recent protests we are already in the middle of a new process of change, which could be characterized as a “revolution of values” rather than a classical political revolution? There are many reasons to this, First and foremost, one should point at the generation gap and the growing sense of disenchantment, disillusionment and frustration that exists with the Iranian youth regarding the Iranian clerical establishment. It goes without saying that since its early days, the Iranian regime has failed to deliver on all its social, political, and economic promises, and it has functioned as a criminal, corrupted and cruel apparatus. Second, the series of sentiments which existed against the Iranian theocratic regime, such as the widening frustration over social restrictions and especially the hijab, have now turned into a legitimacy crisis for the Supreme Guide of the Revolution and the whole Islamic nomenclature in Iran. Third and last, the theocratic establishment and the Revolutionary Guards have been completely take aback by the audacity, velocity and persisting character of the protests of the young Iranian women. This is not only a frustrated generation, but a social category which sees no prospect for a better future in Iran. But at the same time, we are talking here of a new generation which has been exposed in the past twenty years to a different world through the social media. Therefore, of 1265 urban revolts organized between September 16, 2022, and November 11, 2022, in Iranian cities, at least 1,158 protests were led by young women. This shows that the Iranian regime has not been able to cope with the dreams and desires of young Iranians, who are in search of a life style free of the restrictions imposed by a dusty Islamist ideology.

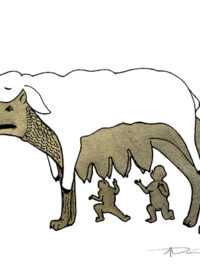

Some non-Iranian observers have wrongly described the massive wave of protests in Iran as a Shi’a Spring, after the Sunni dominated Arab Spring of 2011-2012. However, though Iran is officially a Shi’ite state, unofficially the majority of Iranians have a preference for a secular state, as a reaction to the enforced rules of the Islamic Sharia in the country. The truth is that if the Iranian government were to hold tomorrow a free referendum on the necessary nature of the Islamic Republic, nearly 85% of the Iranian population would clearly oppose it-among them bazaris, villagers, workers and professionals. As a result, for the first time since the victory of the Islamic revolution of 1979, the world is dealing with a new social movement in Iran, which has a vast network of popular groups and political clusters inside and outside Iran. Maybe this is also because women have been at the centre of the current protests, trying to gain back their status of a first class citizen in the Iranian public sphere and the right to divorce and not to wear the hijab, which were the rights they had obtained during the reign of the Shah. The modern agency of Iranian women in post-revolutionary Iran and their struggle against sexual Apartheid obtained a significant structural presence in the Iranian society. Thus, Iranian women became the torch-bearers of the ongoing nonviolent civil resistance against patriarchy and dictatorship in Iran.

Iran today is undergoing a feminist revolution, which is at the same time a revolution of values. One needs to understand how three generations of Iranian women helped to reinvent a new culture of dissent and change in Iranian society by spinning both feminist and democratic values into its fabric. It is through this revolution of values and the feminization of Iranian politics that the younger generation of women in Iran are teaching the Iranian patriarchal and authoritarian leadership that it is time for change. Unfortunately, Iranian clerics and the Revolutionary Guards did not learn their lessons from the Arab uprisings in 2011-2012. However, we need to wait and see how the next few months will unfold in Iran and how the last chapter of the Iranian revolution of values will be written.