A Socialist Mayor for New York? What History Suggests

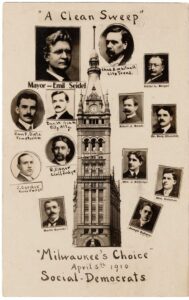

In the spring of 1910 newspapers around the country speculated about what was going to happen in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, as the result of the election of a Socialist mayor in that city. The mayor, Emil Seidel, tried to calm the fears of those who predicted a dangerous revolution was about to take place. Still, after he took office, one writer noted: “Some people are a little surprised that Milwaukee’s socialist mayor did not appear at his desk with a red flag in his teeth and a bomb under each arm.”

Artist: Drew Martin

Similar concerns have been expressed by the possible election of a socialist as mayor of New York in November 2025. While predicting events is always risky and no attempt is made here to do so, a look back suggests a history of socialist mayors that is a bit more comforting to those fearful of a drastic step toward radicalism in New York should a socialist be elected.

The Controversy

In the late 1890s, socialists in the United States began to focus on political activity on the municipal level. These practically minded Socialists with a strong working-class, pro-labor, bias began breaking away from a doctrine-based party of ideologues and outsiders to join an on-going drive to improve the operation, structure, and performance of municipal governments. Many of them hoped to become insiders as office holders at the municipal level, and, from that status, to facilitate the revolutionary cause as much as possible while, and at the same time, bringing meaningful improvements in the quality of life for ordinary people in their communities.

During the early 1900s those, in the right wing, conservative faction of the party, were political action was favored, put considerable emphasis on securing victories on the local level. They argued that winning local offices would give the party a chance to demonstrate that it could be trusted to govern, thus paving the way for success on the state and national levels where more meaningful reforms could be made. It also provided an opportunity to further educate the people in the principles of Socialism, generate support for broader and more fundamental changes, give Socialists experience in governing which would be drawn upon when the opportunity to do bigger things came along, and, on a more practical level, build the party by providing employment for party members. One Socialist editor argued that the prime benefit of capturing local office was that the public “will find that Socialists are merely people who are honestly seeking to promote the public good and the false things that have been told of them will cease to have effect.”

Those on the left side of the party remained opposed to the idea of socialists getting involved in political party activity, feeling it was a waste of time and effort. To them emphasis had to be placed on direct action against employers to bring the capitalist system down as soon as possible. In responding to right-winger’s call for local political activity, leftists supplemented their arguments against political activity in general by arguing, as did several others, that local activity was especially unlikely to accomplish much of anything even if by some miracle a Socialist slate of candidates captured a city or town. In power, they could only do what the state would allow them to – which was not much of real value. If socialists had to get into politics, it would make far more sense to compete for offices on the state and national levels which were in a far better position to do something for the workers.

Beyond the legal and financial limitations on local action, questions were raised not only by Socialists on the left but non-Socialist observers as to whether Socialists in office would want to or dare to do much of anything to seriously promote the Socialist revolutionary cause. Socialist office holders, they argued, were likely to get mired down in trivia, dealing with day to day problems all local officials had to face and take their eye off the revolutionary goals. Such goals, moreover, were likely to take second place at best to the goal of doing what had to be done to win and keep winning office. All in all, they argued, power was going to shift from idealists to practical pragmatic people, bringing watered-down platforms and comprise with the party’s principals in addressing issues.

Along with this came the prediction that simply winning an election would effectively sober up Socialist candidates, making them more conservative and cautions, fearful of taking chances, because they actually had to face reality, make hard decisions and accept responsibility for what happened under their watch. In the end, Socialists in power would wind up losing much of their revolutionary zeal and their parties would be little different than the political parties they condemned. Moreover, whatever meaningful reform, if any at all, that came out of a Socialist administration would likely be undone or used in the interest of the privileged few when the Socialists fell from power as was bound to happen.

Winning Elections

Despite all the controversy, a surprising large number of socialists were elected to office of mayor or a comparable position of chief executive under different titles, such a Village President. Voters were willing to experiment with having a socialist mayor, to see what they could do, and socialist mayors were often able to demonstrate their ability to govern. My research, presented in Socialist Mayors in the United States (2022) found that from 1898 to 1920, voters in 216 municipalities in 34 states chose a socialist mayor or chief executive. Some of these places had more than one socialist mayor bringing the total of mayors to 237.

Socialists started out slowly when it came to victories. With the momentum built up by the victory in Milwaukee in 1910 they hit a high point in 1911 with the election of 80 mayors, doing particularly well in Ohio, Illinois and other places in the Midwest. They held on to 30 or so victories in elections immediately in the few years that followed but picked up only a few wins in the years after 1917, when the “red scare” led to their suppression because of the party’s opposition to U.S. entry in the first world war.

Campaign Postcard of the Social Democratic Party of Wisconsin, 1910

Unlike the situation in New York, today, where we find a self-identified socialist running as candidate of the Democratic Party, nearly all the socialist candidates for office in this earlier period were nominated by local chapters of the Socialist Party of America, over time, officially doing so in compliance with primary election laws the nature of which varied from state to state. Then, as now, a socialist running as a Democrat for mayor in a large city dominated by Democrats, had a far better chance of victory than a candidate of the Socialist Party, though getting the Democratic nomination would as now an earth-shaking event. In the early 1900s, however, socialist leaders were bent on making their party the party of reform (and ultimately more fundamental change) and were inviting others to join their party and support their candidates rather than trying to influence the nominations of other parties (though some party members did do this).

In running for office, the socialist candidates generally sought to assure the voters that they were not, as often charged, wild-eyed un American radicals bent on destruction, but well established citizens concerned about the welfare of the community. They still felt Socialism, meaning the collective ownership of the means of production and the establishment of a cooperative commonwealth would follow capitalism, but only gradually one step at a time through the political process and would be brought about without violence. But rather than talk about these things, they focused on immediate practical problems facing the voters in employment, education, taxation and a variety of other areas. They wanted to win.

Like non-socialist progressive candidates in the races for mayor socialist candidates called for greater honesty and efficiency in running municipal governments. This was a time when the reputation of municipal governments was at an all-time low – they were commonly viewed as captured by corrupt political machines that governed in their own interests. Socialists stood out in their call for greater democracy on the local level, including the addition of the initiative referendum and recall. They also led in the call for the creation of municipally owned and operated enterprises relating to the supply of water, electricity, transportation and many other services.

Many of them saw the Socialist Party’s future closely linked to the growing labor movement. The trade unionists though were practical people. To win them over socialists had to focus more on immediate problems of concern to workers rather than the reasons for wage slavery and what could be accomplished in the eventual revolution. The politically minded Socialists also sought to reach out to the middle class as well as the lower working-class and to farmers as well as industrial workers, and, indeed, to whomever they could get to vote for them. As they saw it, the party had the choice of either becoming politically active in a practical sense or accepting the status of a limited doctrinal party of outsiders basing its appeal on principals and moral argumentation, being kept alive by a small cadre of true believers but having little if any effect on the political life of the country other than possibly in the realm of ideas.

The socialist candidate’s best chance of winning the office of mayor in a general election was in competing in a three way race, facing candidates from both major parties, where they could win by getting the most votes but did not need a majority of the votes, and their worst chances came when Democrats and Republicans fused, so that the contest was one in which the socialist faced a candidate supported by both of major parties and needed a majority of the votes to win. Major party fusing became a major barrier to the election or re-election of a socialist mayor.

Socialists initially felt they would do especially well in large cities because of the concentration of the working class in these places. As it turned out, several factors gave them a better chance in medium-sized and small, often very small, towns than large cities. While the size of the working class was not large enough as a percentage of the total population in most large cities to do much for the Socialists in city-wide elections, it was sometimes large enough in smaller places to have a significant impact on the Socialist vote for mayor. This was true in heavily industrialized and unionized small towns and mining camps where Socialists enjoyed much of their success.

Overall, it was also relatively easy for workers in smaller places to dominate the political process because of their numbers and their economic importance to the community. Workers and their political spokespersons could form social and political ties with local businesses and professionals they patronized and knew on a personal basis. They could find middle and upper-middle class citizens who sympathized with their resistance to the control and abuses of large corporations headquartered elsewhere. More generally, it was also far easier for Socialists to organize and conduct campaigns in smaller jurisdictions and the face- to- face personal nature of politics in these places greatly reduced the significance of partisanship ties, thus taking away a huge advantage enjoyed by major party candidates in larger jurisdictions where party ties were virtually all that most voters knew about the candidates.

Constraints and Accomplishments

Once in office, socialist mayors often found other socialists to be a major problem. They continued to hear complaints from socialists on the left about wasting time and resources doing the wrong thing, though when it came to putting controls on the police during labor disputes, those on the left were happy to have a socialist mayor. Socialist mayors in many places had a difficult time with leaders of the local social party that nominated them. Party constitutions and rules gave local party leaders control over what their nominees did if elected to office. Their nominees signed advanced letters of resignation from their public office, which, should they happen to become mayor or any other official, party leaders could submit to the city council, removing the socialist from office in the event they found the official was ignoring their directives.

Local party leaders expected to call the shots –to them the citizens had voted for and expressed their confidence in the socialist party, not the mayor or another official as an individual. Socialist mayors were generally willing to work with the party but sometimes acted on the assumption that citizen demands and interests, not those of the party, came first and, in the event of a conflict, the mayors had to listen to the people. On these occasions mayors ignored or downplayed the significance of their letters of resignation. Mayor-party disputes produced a great deal of tension and turmoil. The letters of resignation were seldom, if ever, accepted by the councils but on several occasions, mayors had enough with party intrusions and resigned from the party or were expelled from membership in the party by equally irritated party members.

Political Cartoon from Chicago Daily Socialist on Occassion of Seidel’s Election, 1910

Mayors were also often in conflict with other socialist officials including those elected to the city council. Socialists had a hard time agreeing about anything (and still do). In many cases, there were not enough socialists elected to council positions to back up the socialist mayor’s position even if they were inclined to do so, and little could be accomplished. The lack of socialist representation in city councils reflected in part the use of elections at large rather than neighborhood districts to select council people. Socialists opposed inclusion of elections at large as part of the municipal reform package.

Like most politicians the socialist mayors wanted to be re-elected, as evidence of success not only themselves but their party, as a way of demonstrating that a socialist mayor could do the job. Many saw themselves and their party on trial — the voters had decided to give them a chance, to show what they could do and they had to do well, more exactly, do well enough to win enough votes to get returned to office.

When socialists mayors won it was usually because a lot of non-socialists voted for them. Some, perhaps many of the non-socialists, simply voted for change in response to the evident failures of one or both of the major parties. To keep their coalition together socialist mayors had to do more than please the socialists. Re-election required some flexibility as to position taking, a search for issues that would work regardless of how they related to socialism and a toning down on the use of radical rhetoric.

It would be wrong, however, to say that Socialist mayors were only “Socialist politicians” without any fixed principles or beliefs or, alternatively, indistinguishable from Progressive mayors who were Republicans, Democrats, or independents. Socialist mayors were different. They were more ideologically inclined, more innovative, more disruptive of the status quo, and more likely to take on the powers that be. They were also more strongly resisted.

If Socialist administrations did not do much or fell short of expectations it was not because they did not try, but because of the condition of places where they won. Socialist mayors, like other mayors of the time who served in these smaller places were limited by the lack of authority, financial resources, staff, and time brought about by short terms and term limits. Mayors in all cities found that their powers and resources were kept in check by hostile state legislatures (socialists generally had little representation in these bodies) and hostile courts. As suggested, further difficulties stemmed from the conflict within the party between the right and left wings, and the constant interference of party members who insisted on exercising control over the mayor’s actions.

More importantly, just being a socialist also meant being associated with a party that the business community and powerful interests associated with it, perceived as a definite threat. Socialist mayors could only go so far without losing a bid for re-election. As Daniel Hoan, who won several election bids as Socialist mayor of Milwaukee, serving from 1916 to 1940, observed in a letter he wrote a Socialist alderman in 1913, if he became mayor of Milwaukee “I may be able to give them some Socialism” but he’d “have to feed it to them in small doses.”

Socialist mayors played a distinctive role in pursuit of working class objectives and the cause of municipal reform around the country in the 1900-1920 period and, while faced with a number of serious obstacles, and sometimes frustrated because of the slow pace of reform, generally held on, and demonstrated their ability to govern. When it comes to accomplishments one can reasonably argue that Socialist mayors equaled or excelled the performance of other mayors.

*This article is largely drawn from the author’s book, Socialist Mayors in the United States, Governing in an Era of Municipal Reform, 1900-1920.