A Termite’s Guide to Undermining SNAP

Conservatives long have had it in for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly known as food stamps.[1] Ronald Reagan hated it so much that he refused to reverse severe program cuts even when faced with mounting hunger amidst a deep recession, choosing instead to send surplus “government cheese” to states to distribute to the poor. Newt Gingrich nearly derailed his assault on the social welfare safety net in his eagerness to replace federal nutrition programs with block grants to the states, a step too far even for fellow Republicans. The so-called Tea Party made SNAP a target in its budgetary brinksmanship with Barack Obama, and today’s Koch Brother-fueled Freedom Caucus would love nothing more than to shrink SNAP, and the federal government overall, to infant size – making it easier, as anti-tax advocate Grover Nordquist would say, to drown in the bathtub.

Some of this animus is fiscal. SNAP is the nation’s largest food assistance program and its second largest income supplement for the non-elderly, after the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). With annual spending hovering around $100 billion, providing food assistance to around 40 million Americans, SNAP is a target for Republicans looking to slash federal spending.

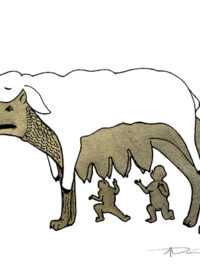

Artist: Drew Martin

But at its core the loathing is ideological, reflecting conservative insistence that any government aid should go only to a narrow tranche of the “deserving poor” – those too young, too old, or too sickly to fend for themselves. Even then, help should be given by local and state governments or, ideally, charity. The 19thCentury beckons.

The language on SNAP in Project 2025, the Heritage Foundation’s urtext for the Second Trump Regime, makes clear the sensibility: “Ostensibly, SNAP sends money through electronic-benefit-transfer (EBT) cards to help ‘low income’ individuals buy food.”[2] Note the snarky adverb and the quote marks. The folks at Heritage apparently doubt that any deserving poor exist, so their zeal to go after the program is no surprise.

However, conservatives know that their hostility to SNAP, like much of their austerity agenda, is not widely shared by their fellow citizens. Sure, most Americans tell pollsters that they loathe “welfare” and that everyone who can work should. When asked, they also support ideals of small government and individual self-sufficiency. All things being equal, Americans are small-government conservatives, right?

Not quite. Social scientists long point out that Americans are ideologically conservative in an abstract way but programmatically liberal when asked about specific government supports. Social Security? Everyone’s favorite entitlement, and you dare not touch it. Medicare? Ditto, not surprisingly. Food assistance to the poor? Yes, even to that: Two-thirds of respondents in a January 2023 YouGov poll supported SNAP, and 40 percent thought the program deserved more funding, not less. While support was highest among self-identified Democrats, two-thirds of Republicans surveyed held favorable views, underscoring that SNAP is seen by most Americans as the safety-net program of last resort.[3]

The budget slashers in Congress and at the Office of Management and Budget know this, and this past summer avoided a direct assault on SNAP in the hilariously named One Big Beautiful Bill, in which they sought budget cuts to offset tax giveaways for billionaires. They made similar attacks on SNAP in the debt-ceiling hostage negotiations with Joe Biden in early 2024. In both instances, the attacks were during struggles over the federal budget, not “normal” legislative deliberation, which pretty much disappeared from the World’s Greatest Legislative Body even before Trump regained the White House.

A bit of history helps. Conservatives have failed over the decades to cut SNAP eligibility and spending during once-regular reauthorizations of the Farm Bill, the omnibus legislation in which SNAP is housed despite being authorized under the Food Stamp Act of 1964.[4] Why is the nation’s largest nutrition program tucked into the Farm Bill? Simple: To ensure urban and suburban Democratic support for welfare for Big Agriculture in return for Republican votes for food stamps.[5] Quid quo pro. Given their need to get votes, most Republicans were reluctant to sacrifice SNAP on the altar of austerity lest their rural constituents suffer reprisals. (Nice corn subsidy you got there. A shame if something happened to it…) They failed in 2014 after two years of budget brinksmanship with Obama, and even in 2018, when they controlled both chambers of Congress and had Trump in the Oval Office. The lesson for conservatives was clear: avoid the “regular” legislative process.

So they again took advantage of the rules on budget reconciliation, in particular its suspension of the Senate’s usual need for supermajorities to overcome objections by the minority. Thus was the OBBB steamrolled through Congress. But even here the assault on SNAP was indirect. Nowhere in the Blobbb is there an outright cut in the program’s budget, in contrast to what happened to foreign food aid and public broadcasting. Instead, conservatives inserted several administrative termites in the program’s foundation. Left alone, the termites will nibble away, and over time SNAP’s house will collapse. Here’s how:

Step 1: Layer on administrative burdens

SNAP is an entitlement program authorized under the Food Stamp Act of 1964. If you qualify, you get a level of benefits based on household income and size as determined by Congress and the US Department of Agriculture, which oversees the program. Unless Congress restricts the SNAP budget, which it hasn’t tried to do since the 1990s after repeatedly overturning its own caps, the only way to cut spending is to change program rules to make it harder for eligible households to apply, or to renew benefits. To do so conservatives like to layer on what public administration scholars Pamela Herd and Donald Moynihan term “administrative burdens.”[6] Such rules are designed to make life harder for those seeking government benefits, unless they are from favored groups like senior citizens, veterans, and farmers. The very nice people at the Social Security Administration are praised for their willingness to help their constituents get the benefits they rightly deserve. The folks at many state welfare offices, not so much.

Among SNAP’s administrative burdens is every conservative’s favorite stalking horse, work requirements for Able Bodied Adults Without Dependents, which with the OBBB now apply to adults 18-64 (previously 18-52) and to once-exempted former foster youth age 18-24, veterans, and homeless people. Work requirements on so-called ABAWDs have been a feature of SNAP since 1971, when southern conservatives insisted them in return for supporting expanded program eligibility and higher benefits. Rules on work requirements were intermittently tightened and loosened in ensuring decades depending on the political winds, and attained current form in 1996, when Gingrich and Company imposed new SNAP work rules as part of so-called welfare reform. Those rules mandate that to get benefits ABAWDs had to work at least 20 hours per week or be enrolled in a state-sponsored employment and training program, and they could only get benefits three months over any three-year span.

Independent scholars who study work requirements identify three problems with them. First, and despite the popular image promoted by conservatives, most adults in SNAP households who can work already work. They just don’t make enough money to feed the household through an entire month. Indeed, economists point out that SNAP has become a support for the working poor, not the destitute.[7] Those who do not work usually have something else going on in their lives, from physical and mental health problems to caring for children or elderly relatives. Often a bit of both.

Second, there is little evidence that work requirements incentivize work. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, which funds considerable scholarly analysis on work requirements, put it bluntly: “Decades of research show that these policies do not move people off assistance and into self-sufficiency. Instead, work requirements harm health, keep eligible people from obtaining needed assistance, and drive people and families already struggling to make ends meet deeper into poverty.[8]

Third, inflexible work requirements impose high administrative burdens on potential enrollees. Making it harder for otherwise eligible adults to obtain or renew benefits tends to discourage application at all and makes it easier to deny or revoke benefits for those who do apply. The result: fewer enrollees, and lower program spending – the entire idea.

Less appreciated is the administrative burdens inflexible work requirements place on the states, which must ensure that applicants meet considerable paperwork requirements to prove their eligibility, and do it all over again each time households seek to renew their benefits, which for ABAWDs is every three months. Put simply, work requirements are difficult and costly to administer, and states long sought waivers from enforcing them.[9] No more: one provision tucked into the OBBB now restricts states from seeking waivers on the three-month benefit time limit for ABAWDS unless an area has 10% or higher unemployment rate (Alaska and Hawaii get a little flexibility).

Put simply, broader and more rigid work requirements will impose more and costlier burdens for the states – just as the federal government is about to make the situation worse.

Step 2: Offload administrative costs to the states

While the federal government (still) fully funds SNAP benefits and sets rules on eligibility, the program is administered by the states, which obviously incur costs in screening applicants, calculating benefits, and ensuring program compliance. In the Food Stamp Program’s first decade the federal government picked up only 30% of these administrative costs, leaving states on the hook for the rest. As one would expect, some states regarded those costs as prohibitive or not worth incurring and did little to nothing to enroll technically eligible households. In 1974, Congress raised the federal portion to 50% precisely to entice all states to participate. Program enrollments climbed thereafter, as intended.

The OBBB returns us to the Bad Old Days. Starting in October 2026, states will be required to cover 75% of SNAP’s administrative costs, the highest fiscal burden in program history. While for large states like California and Texas this will mean hundreds of millions in new expenses, even small states will have to pony up more to implement an otherwise federal program.

The likely impact? Unlike the federal government states cannot run budget deficits, so higher costs to administer SNAP will force them to cut elsewhere or to do as little and as cheaply as possible to enroll technically eligible households. You would not be wrong if you bet that many, if not most states will do the latter. Deterring applicants is a cost-effective strategy. Let the austerity commence.

Step 3: Punish States for Administrative Errors

Starting in October 2027 – safely after the midterms – states with high SNAP “error rates” will be required to will pay up to 15% of program benefits, the first time in the sixty plus years of program history that the federal government will renege on its commitment to cover those costs. “Error rates” are not the same as fraud by enrollees or retailers, both of which are less common than the loudly parroted anecdotes on Fox News have one believe. Error rates reflect mistakes by states in enrolling applicants. Some errors are in approving benefits at all, but most are in calculating benefit levels – typically too high. The USDA in the past tried fining states with high administrative error rates but found that offering bonus funds to states with low error rates was a better way to encourage more accurate program implementation.

The likely outcome of this new rule? States will be desperate to avoid paying millions in program benefits on top of the extra administrative costs already layered on them, so they will focus on reducing error rates to as close to zero as possible. How best to do this? Make applying even more onerous. Demand more paperwork. Deny benefits to any but the most obvious and most “deserving” cases. Some states may even decide that SNAP isn’t worth it. Despite SNAP’s status as a federal program, states are not required to participate, although all have since the early 1970s because of federal inducements. While I doubt most states will pull out – SNAP still is seen as “free” federal money with considerable economic multiplier effects – they can do as little as possible to administer it, functionally the same result. Where you live will again determine your access to food assistance.

The rules changes in the OBBB thus insert administrative termites into SNAP’s foundation.

Over time, the combination of higher administrative costs and the prospect of being forced to pay some portion of program benefits will lead to wildly variable state program administration, lower enrollments, and weakened program political clout as SNAP serves fewer and more marginal households. If enacted in full, these changes will put SNAP into a programmatic death spiral, just as conservatives intend. The bathtub awaits.

Notes

[1] See Christopher Bosso, Why SNAP Works: A Political History – and Defense – of the Food Stamp Program (University of California Press, 2023).

[2] The Heritage Foundation, Project 2025: A Mandate for Leadership (Wasington, DC: 2024), p. 299.

[3] Linley Sanders, “How Americans evaluate Social Security, Medicare, and six other entitlement programs,” YouGov, February 8, 2023; at https://today.yougov.com/topics/politics/articles-reports/2023/02/08/americans-evaluate-social-security-medicare-poll

[4] Each ‘farm bill’ is titled something like the Agricultural Act of 2018 but is known colloquially by its generic name.

[5] See Christopher Bosso, Framing the Farm Bill: Ideology, Interests, and the Agricultural Act of 2014. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2017.

[6] Herd and Moynihan, Administrative Burden: Policymaking by Other Means New York: Russell Sage, 2018.

[7] See, for example, James Ziliak, “Why so many people on SNAP?” in Judith Bartfeld, et al., eds, SNAP Matters: How Food Stamps Affect Health and Well-Being (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2015):

[8] Issue Brief, “Work Requirements: What Are They? Do They Work?” Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, May 2023.

[9] For example, Ed Bolen and Stacy Dean, “Waivers Add Key State Flexibility to SNAP’s Three-Month Time Limit,” Center for Budget and Policy Priorities, February 6, 2018,