Roger Frie’s Edge of Catastrophe: Erich Fromm, Fascism, and the Holocaust

Roger Frie’s new book on an underexplored aspect of Fromm’s life, namely, his experiences with Nazism and the Holocaust is a significant—indeed, groundbreaking—contribution to Fromm scholarship as well as to Holocaust research. In addition to offering a thoughtful and meticulous analysis of parts of Fromm’s life hitherto generally hidden from view, the book explores a range of topics that are germane to Holocaust research, including racial hatred and bigotry, oppressive socioeconomic structures, ethics, and questions of personal and collective responsibility in the face of oppression and genocide. On a personal note, I must confess that as I started reading this book, my engagement with it was coloured by a bias of sorts. I was initially convinced that the subject matter of the book would likely have been approached with more nuance, care, and sensitivity by a Jewish author, one who is also familiar with Fromm’s work or is a scholar of Fromm. It seemed obvious to me that the task this non-Jewish author set himself in tackling this important topic was too great of a challenge and that the text would likely miss important nuances with respect to Jews’ collective traumas and fall short in important respects. I was delighted to be proven wrong.

The book has many strengths, and one such strength is that the author manages to balance historical, psychological, and philosophical perspectives in his illuminating considerations rather skilfully and with considerable clarity. For example, Frie weaves commentary on Fromm’s early life with insights about the nature of trauma, loss, and pain as he constructs a compelling narrative of the formative influences in Fromm’s life and intellectual development and convincingly demonstrates that Fromm would later turn to writing and activism as a way of coping with the horrors associated with the Holocaust. One of the book’s other strengths is that the author does not shy away from offering criticisms of Fromm’s views on various issues, including his views on and embrace of matriarchy (69-70) and his (undoubtedly naïve) willingness to accept Albert Speer’s questionable account of his own involvement in carrying out the Holocaust (134-139).

In chapter 1, Frie presents the very personal and emotionally charged correspondence between Erich Fromm and his close relatives who remained in Germany as Nazism was gaining momentum and the Holocaust loomed on the horizon with acuity, tact, and sensitivity. The letters in question were exchanged over the course of the months leading up to the extermination of Europe’s Jews in the Holocaust and as deportations to concentration and death camps were beginning to take place. Among other things, they document the growing anxiety and feelings of powerlessness among German Jews who remained behind, not able to make it out of Germany in time. Those who were fortunate enough to leave Germany early on, like Fromm, had to live with the knowledge that many of their relatives who remained behind were facing an uncertain future. As what the Nazis were planning came into sharper focus, the anxiety and guilt accompanying this knowledge naturally mushroomed. Fromm did everything in his power to secure his relatives’ freedom and facilitate their escape, including aiding them in obtaining exit visas and travel documents. Some of the relatives he was closest to perished in the Holocaust despite these admirable efforts. The author analyzes these correspondences attentively, bringing into focus their personal dimension, which is coloured by uncertainty, sadness, anxiety, and grief (chapters 1 and 2). We are also given a glimpse in chapter 1 of the vibrancy of German Jewish communities in Germany prior to the emergence of Nazism, with the founding of the popular Jewish Free Learning Center in the years before the war being a notable case in point (21).

Frie perspicaciously observes that for those Jewish individuals who managed to make it out of Germany in time, knowledge of the catastrophe and the loss of friends and loved ones would beget trauma, guilt, and sadness that would accompany them for the rest of their lives (111-114). A case in point is the tragic fate of Fromm’s second wife, Henny Gurland. It is likely the case that during her marriage to Fromm her psychological well-being was undermined by her tragic personal experiences with Nazism and the Holocaust. Noteworthy in this regard is that she appears to have taken her own life (113). It is also worth mentioning in this connection that she accompanied Walter Benjamin on his ill-fated journey of escape from Europe as the Holocaust was unfolding and was with him during the last hours of his life after he swallowed a lethal amount of morphine pills (106-110). On the other hand, Frie also presents a case study in human resilience as he explores the extensive troubles faced by Fromm and his relative, Heinz Brandt, during the Nazi period and beyond. Brandt was forced into confinement for many years yet, with help from Fromm and others, managed to survive and apparently even thrive. Both he and Fromm clearly chose a life affirming path despite the numerous hurdles and tragedies they had to endure throughout their lives, and as Frie points out, their shared interest in writing and activism was one conspicuous manifestation of this biophilic orientation (122-125). True, Fromm’s work as a public intellectual and prolific output were undeniably shaped and informed by the myriad traumas and losses he endured as a result of Nazism and the Holocaust (124-128, 145-147). It is important to recognize, however, that Fromm’s decision to become a public intellectual was driven not only by trauma and a sense of responsibility but also by the affirmation of life and its possibilities, including that of a healthy society. Perhaps this crucial point could have been made more explicit by the author.

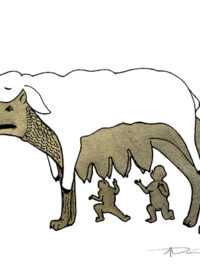

In chapter 2, Frie provides an overview of factors and events in Fromm’s early life, including his Orthodox Jewish upbringing and World War I, that would play a pivotal role in shaping his outlook later in life and his response to Nazism and the Holocaust (59-61). Fromm’s terrifying and life-altering experiences with German nationalism ensured that Fromm’s mature outlook would be staunchly anti-nationalistic and, as Frie notes in a subsequent chapter, this position informed Fromm’s hostility toward Zionism (145-147). Frie also engages in an interesting discussion, throughout chapter 2 and with a focus on the work of the German artist Käthe Kollwitz, of the power of art as commentary on social issues and potentially even as a form of resistance to various forms of oppression. He also notes here that Fromm understood early on in his career as a writer that patriarchy lends itself to and reinforces authoritarianism and saw challenging it an ethical imperative (69-72). Admirable and bold is the author’s willingness to confront his own family’s Nazi past (95-98). He discusses his grandfather’s association with the Nazi party in some detail, and contextualizes his family’s extended silence on the issue as he was growing up in terms of the broader problem of Germany’s reluctance, in the decades following the war, to acknowledge and reckon with its Nazi past and the complicity of many of its citizens (116-122). It is clear that Fromm’s inclination to speak up and take principled positions on a host of social issues in the wake of the Holocaust, including anti-Black racism in the United States (126-127), has to be understood, as least in part, in terms of his awareness of the terrible things people can facilitate and become complicit in when silence, indifference, and denial are normalized.

Equally commendable is the author’s nuanced and thoughtful discussion of Antisemitism in the American context and its likely effect on what Fromm and his Frankfurt School colleagues felt they could and could not express in their writings in their new home country (100-102). As the author notes, “Antisemitism was also strongly ascendant in the United States, the very country where the Institute and its members and associates had found a new home” (100). The fact that Fromm and his colleagues were left-wing Jewish intellectuals would have made them targets of anti-Jewish bigotry (100-101). This is a very important point, one easily overlooked against the backdrop of the catastrophic consequences of antisemitism in Nazi Germany. As the author notes, it is certainly possible that American antisemitism played a role in Fromm’s reluctance to directly address antisemitism in Escape from Freedom, which was published in 1941, but he concludes (rightly, in my opinion) that given Fromm’s courage and “willingness to speak out and challenge the status quo throughout his career” it is probably the case that Fromm’s choice not to address antisemitism directly in that book has more to do with the trauma and pain he was experiencing as he was working to save his family members who remained in Germany (101).

Frie also explores Fromm’s tense relationship with the Institute for Social Research and eventual departure from the Institute as he embraced a novel framework for analyzing social psychological phenomena that was anathema to the other leading members of the Institute, including Horkheimer, Adorno, and Marcuse (88, 103). In chapters 4 and 5, Frie accomplishes a number of things, including offering an engaging discussion of ethics and social responsibility as well as the constructive and transformative power of love, hope, and human solidarity. But perhaps most notable among these accomplishments is bringing Fromm into dialogue with a number of prominent Jewish intellectuals who were Fromm’s contemporaries, including Hannah Arendt, Primo Levi, and Martin Buber.

I would now like to offer several, very minor criticisms of the book. First, the comparison of the affinities of Fromm’s ideas with those of Buber is fruitful and promising, and should have been pursued further (154-155). Both Fromm and Buber are prominent philosophers of dialogue and Fromm scholarship can greatly benefit from a more thorough exploration of convergences and divergences in their positions and views. Second, it would have made sense to devote an additional chapter to reflecting on the implications of the letters and correspondences presented and discussed in chapter 1. The book being structured the way it is, Frie’s consideration of them in this chapter is eclipsed by the following chapters and the reader is likely to lose sight of their centrality to the evolution of Fromm’s unique outlook and insights. Additionally, it would have also made sense to devote more space to a discussion of the uniqueness and contemporary relevance and implications of Fromm’s social psychological insights. There is, after all, much to say on the subject with Trumpism and other authoritarian populisms lurking in the background. The author himself acknowledges as much with respect to Escape from Freedom in particular: “Escape From Freedom is relevant in other ways too. Fromm’s account of authoritarianism, especially in times of uncertainty, helps to explain the attraction of right-wing populism” (104). Indeed, the themes of evil, racial narcissism, human destructiveness, and willing submission to powerful and manipulative leaders, introduced by the author in the penultimate chapter, have an eerie contemporary resonance that he could have engaged further and explored in more detail. It would have been helpful to have clearly formulated insights about how Fromm’s emphasis on the socioeconomic conditions that give rise to authoritarian politics (132), and perhaps texts like Escape from Freedom and The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness (with its unique and helpful typology of aggression) in particular, can inform analyses of the resurgence and appeal of authoritarianism across the globe today. The author notes: “Fromm thus reminds us that the potential for evil is directly related to the conditions and contexts in which it emerges. In order to guard against malignant aggression, we must work together toward ensuring a healthy and functioning society” (132). I suspect most scholars of Fromm and the Frankfurt School would agree with this conclusion. Yet it begets the obvious question, what exactly does a healthy and mature society look like and how do we get there? Fromm was adamant that socialism is the answer, as Frie notes more than once in the book, but it is unclear whether the author himself shares this view. It would have made sense to devote at least a few pages to a discussion of this pressing question.