The Metonymy of Light: Three Early Works by Stan Brakhage

At the heart of preeminent American avant-gardist Stan Brakhage’s cinema, there lies a central tension or struggle between abstraction and representation. Film critic and Brakhage chronicler Fred Camper has posited The Riddle of Lumen (1972) as a kind of central work in this regard, arguing for that film as a turning point in Brakhage’s work which anticipates his later “closed-eye vision” films (Roman Numeral Series (1979), Arabics (1982), Egyptian Series (1983)) in its steps toward a further degree of abstraction than had been previously seen in his work, while still retaining in the finished film a faint semblance or recollection of the objects being filmed. If Brakhage’s later “closed-eye” films might be said to give themselves over more completely to abstraction, then some of the films that followed these mysterious and jewel-like works, such as A Child’s Garden and the Serious Sea (1991), seem to forge a paradoxical unity out of this central difference, wherein floating bodies of light become paired with photographic effects within spaces of skeletal physicality. In this regard, light itself occasionally seems to acquire a metonymic or metaphoric status in Brakhage’s cinema, a capacity to hold a part of the meanings of the objects that it touches and illuminates, as well as a capacity to extend or transform those meanings. Of course, the luminous bodies that the viewer encounters in Brakhage’s cinema are not merely meant to illuminate objects in the physical world, but also in some sense become the main subject of some of Brakhage’s films, at times rendering material entities in the physical realm rather ephemeral. (Camper has himself called The Riddle of Lumen an “inventory of different kinds of light,” a notion which might also apply to the filmmaker’s more famous The Text of Light (1974).) Though this argument might be said to apply more meaningfully to Brakhage’s photographic works than it does to his later hand-painted films, it might be worth examining the different qualities that bodies of light possess, acquire, and emanate across a range of Brakhage’s films in relation to other aspects of form.

Stan Brakhage, The Wonder Ring (1955)

Brakhage’s The Wonder Ring (1955), which has been regarded by the critic Michael Sicinski and some others as the filmmaker’s earliest masterpiece, uses various forms of glistening luminosity to create palpable visual textures which transform the space of New York’s Third Avenue elevated railway into a charged, impossible, and otherworldly zone. (This film was commissioned by the avant-garde artist Joseph Cornell, who not long after made his own reversal companion piece comprised of outtakes from Brakhage’s film, entitled Gnir Rednow (1955).) Following the film’s distinctive, hand-scrawled “By Brakhage” title cards, the viewer becomes sensitized early on to the ways in which light will become a source of enchantment and delight in this film. In the second shot, Brakhage applies an upward-vertical, hand-held camera movement to a shot of the staircase leading up to the elevated railway station. But because Brakhage elects to use only readily available lighting sources for this film, and because there are no artificial sources of light in this particular space, the industrial staircase itself becomes very difficult to discern within the enveloping darkness of the stairwell. Rather, the abstract pattern of light glowing onto the stairs from the sun outside, fragmented in spots by shadows from the hand railing, appears to be the “main subject” of this shot, a tilted vertical grid of long, rectangular blocks which Brakhage’s camera appears to survey with reverence, contemplating it slowly upward like a rising, majestic skyscraper. The luminous pattern is both the main interest of the composition and appears to supersede in importance the industrial structure which it touches. Though light will be used in more complicated ways later in the film, this early shot seems to in some sense give the viewer instruction on how to proceed in functionally reading the rest of the film, a way of subtly suggesting that a sensitivity to light will be required to unlock the mysterious nature of this work.

Brakhage increases the complexity of his approach by collecting and contrasting several different types of light in the next sequence of shots, which examine the elevated floor and platform of the railway station before the enchanted ride has commenced. Brakhage begins this section of The Wonder Ring with a series of horizontal pans which survey details from the upper walls of the station, replete with different kinds of signs, windows, and window frames decorating its chipped walls. Brakhage here inaugurates a technique that he will deploy throughout the rest of the film, in which he reverses the direction of apparent camera motion from the shot that preceded it, creating a reversal of movement that imbues the paired shots with a feeling of symmetry even when they are not surveying the exact same section of the station, and which seems intended to create a kind of hypnotic effect on the viewer through its illusion of back-and-forth motion. In these shots, the viewer may observe at least four different kinds of light: 1) artificial light emanating from visible sources within the shot, such as lighting fixtures; 2) artificial light emanating into the shot from unseen sources (these first two kinds of light often create striking, contrasting colors within the frame); 3) natural light emanating into the station from the sun outside; and 4) reflected light beaming off the glass windows around the station, which act as mirrors and sometimes show a reflection of their source (this last kind of light can be either natural or artificial).

Stan Brakhage, The Wonder Ring (1955)

The voluminous, varied array of types of luminosity being collected here (Camper’s decision to call it a kind of “inventory” feels apt) might at first seem an attempt to disorient the viewer, but by being paired with the hypnotic reversals of Brakhage’s subjective “camera-eye”, they instead have the effect of making strange (in the Shklovskian sense of the term) a familiar public space, disrupting our perception of the everyday and imbuing the open-air chambers of the station with a charged and vibrant atmospheric potency marked by its utter unfamiliarity. While light was first introduced in The Wonder Ring as a source of enchantment and delight, it now also seems to carry an air of unfathomable mystery, an otherworldliness which becomes one of the film’s key strengths. Layered reflections and unaccountable, floating orbs of rich hue alter our perception of the structural surfaces which they glisten and glow upon. Softly textured halos around objects and lighting fixtures become combined with multiple reflections viewed simultaneously, creating a kind of alien collage of luminous effects. The lulling reversals of the camera seem designed to gesture the viewer deeper into this world which has gradually become one of deep visual strangeness.

Once the train ride which will comprise the remainder of the film begins, hitherto unseen effects emerge: while previous camera movements in the film had been generated by the motion of Brakhage himself, he now contrasts these generated movements with the automatic movement provided by the train itself, allowing his camera to remain still while the viewer is granted scenic views of the city which fly past almost as quickly as one can apprehend them, recalling the first camera movement films of the late nineteenth century, done by the Lumière company, which were also created by placing the camera aboard a locomotive. While these spectacular views of 1950s Manhattan in bright, natural light might at first seem like a startling contrast to the beginning of the film in their uncluttered splendor, Brakhage quickly distances the viewer from the outside world by privileging shots which emphasize the mediated quality of our vision: window reflections create odd, naturally derived superimpositions which act as barriers between the camera/viewer and the architectural structures on display, and Brakhage twice includes an effect in which the glass panes of the train window create a striking rippling effect across the buildings, optically transforming them from a solid state into a kind of liquid one. The way these compositions seem to reflect on the various ways that light passing through a surface (in this case, glass) can alter one’s perception of the exterior, material world serves as a reminder that the tension between abstraction and representation was present in embryonic form even in this early work by Brakhage, though here this fundamental tension feels more playful and enchanting than serious and intense, a magic carpet ride of sorts.

The overt beauty of these views of the urban world beyond the railway become interspersed in the editing with more hermetic shots of details within the interior of the train car, which some viewers have commented on as feeling strangely depopulated of passengers, but this may merely be because Brakhage’s camera displays an interest above all in non-human entities. One memorable shot in this section contrasts the shaking, turbulent motion of the train car doorway with the transitory serenity of patches of sunlight pouring onto the carriage floor. The way these blocks of natural light flash in and out of existence (depending on whether they are being blocked by structures from the outside world) seems to act as a foreshadowing to the film’s fourth and final section, in which light gradually recedes, becoming enveloped and fragmented by the darkness of shadows created by the contours of the city. Brakhage announces the arrival of this fourth section by having the train ride begin to move in the opposite direction, which can be seen as a kind of automatic reflection of the earlier reversals of movement he had been performing at the station, an eloquent formal device writ large.

Brakhage’s prior interest in forms of artificial light gradually decreases and fades out in this last section of the film, becoming replaced by shots in which pieces of reflective natural light, viewed through the train windows, have been reduced to discrete blocks within images of greater darkness, possibly filmed during a later part of the day. The earlier tone of playfulness becomes replaced in this section by a feeling of hushed reverence, with Brakhage in some sense appearing to lay bare the secret that light had been the true subject of his film all along. A large part of the pleasure of viewing The Wonder Ring resides in the alert viewer’s gradually increasing awareness of how to perceptively read the film, how to become sensitive to its disparate and contrasting luminous properties. What this ultimately amounts to is a work in which the effects created by light itself, and the way that these effects intersect with movement, seem to contain a greater part of the work’s pleasures and meanings than the objects and surfaces they are cast upon. The film is less a document of the Third Avenue elevated railway than it is a tour of light-effects both spectacular and spectral. The metonymic relationship between light-object and material-object, the way that physical structures become reflected but also distorted into glowing, otherworldly entities, acquires a powerful sense of mediation which makes The Wonder Ring a special and groundbreaking work in Brakhage’s early filmography.

Stan Brakhage, Window Water Baby Moving (1959)

In Brakhage’s later film Window Water Baby Moving (1959), a genuine classic of the American avant-garde which records the birth of the filmmaker’s first child, light seems to forcefully assert its innate qualities of elemental intensity in a way which gestures the status of the film away from being a mere personal documentary on a natural event, instead rendering the work into a kind of love-film. The varied ways in which natural light interacts with and illuminates the small, closed set of physical entities one encounters in the film, the way that light at times seem to match in intensity the pains of childbirth while at other times existing outside of it, imbues this pungently physical work with a mysterious and charged air of ritual. Indeed, the very title of the film, “Window Water Baby Moving,” when uttered aloud repeatedly, begins to take on a quality of hypnotic incantation or spell, rhythmically gesturing the speaker toward a different and perhaps trance-like state, a quality which becomes reflected in the film’s repetition of shots. The bewitching, incandescent quality of the colored light in this film, and the way that it interacts with the list of other elements revealed in the title, seems to possess a similarly transformative energy. It may be easy to overlook the fact that the first word of this title, “window,” is also the first thing one sees in the film’s opening shot, an opening to the outside world through which light can pass and illuminate the proceedings. The open window of the Brakhage home, shown repeatedly throughout the film, is no less important to an understanding of the work than the “water” or the “baby” are.

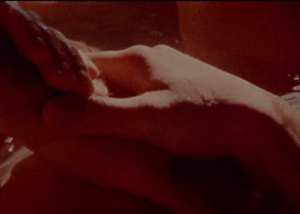

Window Water Baby Moving neatly divides itself into sections that are clearly separated by frames of black leader which act as caesuras, brief moments of respite which allow the film to approximate a sense of breathing as well as a form of poetry. (In this latter regard, the film resembles a much later Brakhage film, the exquisite, hand-painted work From: First Hymn to the Night – Novalis (1994), in which hand-scrawled frames of text writing out fragments of a German romantic poem are deployed throughout the work, rather than merely at the very beginning or very end as they are in most of Brakhage’s films.) In the first section, the interplay of incandescent red light and a purer, but no less intense, white light creates stunning, rippling illuminations on moving water and human skin, often simultaneously as one sees Jane Brakhage’s various limbs and body parts become submerged into the water of a bathtub. The pervasive red light filling the frames of these early shots seems to convey a potent sense of atmospheric foreboding, though crucially not a kind of foreboding which implies a spirit of malevolence or menace (as reddish light will in Brakhage’s later The God of Day Had Gone Down Upon Him (2000)), but rather a deep sense of anticipation, a kind of bracing of subject, filmmaker, and viewer alike ahead of the difficult and painful (yet also beautiful and natural) event which is about to unfold.

Brakhage often films a section of Jane’s body engulfed in total light, while another section remains in a darker visual field, illuminated only by a faint, wavy glow from the water. While it seems unlikely that the filmmaker was giving much direction to Jane during the progression of such an important event in their personal lives, this unusual way of lighting the human figure has a way of gesturing the viewer toward a more natural and more primal state, allowing us to, for once, regard the human body with a kind of purity of vision and in a way which feels divorced from the way nude bodies have been presented in most commercial contexts, without any trace of consumerism or pornography. (In this regard, the film might be cross-referenced with Brakhage’s Wedlock House: An Intercourse (1959) from the same period, which makes fornication look as strange and beautifully alien as childbirth does here.) This sense of returning to a kind of pure state of vision remains one of the clearest and most successful demonstrations of Brakhage’s quest, as discussed in his Metaphors on Vision (1963), of restoring the perceptual visions of infancy, of the way a child might see the world.

Once Brakhage begins to show Jane’s water-dappled belly heaving from contractions, he cuts to a shot of her face in labored concentration, and at this moment an explosion of blinding white light fills the frame, temporarily cutting off the viewer’s access to any subject in the visual field. This moment remains striking for the way that light seems to momentarily take on the painful intensity of Jane’s labor, or at least for the way that a luminous body has temporarily become aligned with a physical state within the vision of the film. This moment might also be regarded as a kind of apotheosis, a climax or turning point of sorts, which is quickly followed by a series of very lovely shots of the filmmaker kissing his wife, which represent a tonal shift. The filmmaker’s decision to include his own presence and his own face in the finished film remains an interesting one, as Window Water Baby Moving differs from many (but not all) Brakhage films in this respect, and the shots in which he and Jane occupy the same frame appear to be bathed in a softer, more golden light which emanates a feeling of sanctity. (This is one of many aspects of the film which seem almost miraculous, as though Brakhage could not have foreseen or authorized it due to the spontaneous nature of the event he was filming, and which gives this film a special status within his vast filmography.)

Stan Brakhage, Window Water Baby Moving (1959)

It’s in these shots of the filmmaker touching his wife’s labored body, while still somehow remaining sensitive to the changing qualities of light from shot to shot, that the film announces itself as a form of love-film, not a romantic film in the conventional sense but a work which appears to show heterosexual love in a way which approaches nature and biology. Yet far from being documentary-like or coldly scientific, as this subject matter might typically call for (and which the unflinching shots examining female genitalia and its liquid discharge sometimes are), the film instead communicates a deeply emotional current of this love between man and woman which seems to be achieved through the film’s sensitivity in capturing different forms and textures of luminosity. If one were to view this film alongside Brakhage’s The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Eyes (1970), which examines the human body after the moment of death just as this one does at the moment of birth, one would observe stark differences in the way that Brakhage lights and films the human figure. While the later film might be said to veer toward the status of documentary in its more sterile lighting and frontal presentation, the light in this earlier film grants it an awesome sense of beauty which at times borders on holiness. But the way that Brakhage achieved these effects in Window Water Baby Moving ultimately remains mysterious, a source of the film’s seemingly inexhaustible fascination and richness.

Though Window Water Baby Moving does not delve as forthrightly into abstraction as The Wonder Ring and most of Brakhage’s other films do, its journey from bewitching nature-ritual to rapturous love-film becomes achieved in part through a sensitivity toward the various ways in which luminosity may alter the viewer’s perception of the human figure and human action. And while it might be added that these two films have an antithetical relationship to one another in terms of the respective levels of interest and disinterest they display toward the human, in both cases light seems to extend the meanings of what Brakhage chooses to show us, in a way which departs extremely from, and goes beyond, the way lighting typically functions as mere accent in most forms of non-experimental cinema. While light-effects in The Wonder Ring seem to exist as discrete elements within the image (reflections and patterns which seem to float and hover around objects, operating distinctly from one another), the quality of the light in Window Water Baby Moving possesses a more totalizing effect, subjecting all objects and entities within the frame to undergo a kind of mass transmutation. The critic P. Adams Sitney identifies Window Water Baby Moving as one of a group of “lyrical films” which Brakhage made between his great breakthrough work Anticipation of the Night (1958) and his major “epic of mythopoeia”, Dog Star Man (1965). But while Anticipation of the Night predates Window Water Baby Moving in the chronology of Brakhage’s filmography, it exceeds its successor in terms of both length and formal complexity, while also offering a broader range of variation in luminosity.

Stan Brakhage, Anticipation of the Night (1958)

While the nature of the event being filmed in Window Water Baby Moving occasionally brought issues of authorship and intent into question, one never feels this way when confronted with the grand design of Anticipation of the Night, a work which self-consciously divides itself into sections, movements, and reprisals, and which evinces a structural ambition up to that point unseen in Brakhage’s oeuvre. In Anticipation of the Night, the relationship between light (both natural and artificial) and movement (both camera movement and figurative movement) implies an act of searching, perhaps a kind of spiritual searching, which forms a structural counterpoint against the film’s submerged narrative, which acts as an intimation of suicide. Broadly speaking, the compositions one encounters in this film may be divided and categorized into two dominant strains: 1) shots which provide information about the film’s central figure, clearly a man, and often interpreted as a version of the filmmaker (which seems appropriate given the personal and subjective nature of Brakhage’s cinema), and 2) more abstract and external shots which feel isolated from any narrative or subtext, and which as such may be read more openly, perhaps as subjective visions of what the film’s central character is seeing or perhaps not. It’s in this second strain that a tonal counterpoint becomes developed and resides within the work, one which allows the film to avoid becoming overly monotonous or depressive, thereby enriching its emotional texture and thematic complexity.

Within the first compositional strain, Brakhage often films expressionistic shadows moving within vivid pools of bright, natural light in darkened interiors as a way implying figuration without photographing himself or another human subject directly. These shots, which begin quite early in the film’s duration, might be described as quite unlike anything one sees in Brakhage’s subsequent work, not only because of their angular expressionism, but because they seem definitively intended to impart an aspect of drama onto the film – not precisely a sense of fiction or of narrative, but certainly a sense of internal conflict and, given the powerful feeling of solitude that they convey, perhaps even a sense of anguished personhood. Though Sitney has put forth the argument that Anticipation of the Night represents a break from Brakhage’s earlier psychodramas and the beginning of his period of lyric films, it might be more accurate to say that the film represents a kind of grappling, a struggle between the psychodrama and the lyric film, in which the filmmaker has not yet completely ridded himself of the last traces of the former. In this regard, one could even surmise that Anticipation of the Night is a film that Brakhage needed to make as a means of becoming the artist we now know him to be.

The second compositional strain might be described as much more characteristic of Brakhage’s mature style in the sense that its shots more closely resemble the kinds of images one sees in later films. Most critics, Sitney included, have chosen to interpret these shots (which far outnumber those of the first strain in their frequency of appearance) as being visual representations of what the film’s central male figure is optically seeing. (Sitney: “The great achievement of Anticipation of the Night is the distillation of an intense and complex interior crisis into an orchestration of sights and associations which cohere in a new formal rhetoric of camera movement and montage.”) While this interpretation does carry some validity, the body of the film itself doesn’t seem to be inviting the viewer to definitively read it in this way, and these compositions might instead be regarded with equal validity as free-floating entities which exist in counterpoint to the veneer of drama one encounters in the first strain, a lyrical opposition which works to corrode the psychodrama undergirding the film.

Even by the high standards of Brakhage’s cinema, Anticipation of the Night remains a stunning visual tour-de-force by virtue of the sheer variety of types of shots one encounters in this second strain, a sense of variety which extends to the objects being filmed, the types of movement which are enacted by the camera, and the types of luminosity which are captured by the camera, all of which combine to create near-constant feelings of surprise within the viewer through their contrastive placement in the editing. Rapid, back-and-forth hand-held camera movements upon brightly artificial light, generated by streetlamps and amusement park rides filmed in total darkness, provide a sense of thrilling visual pleasure which bears resemblance to a fireworks display, and which starkly contrast with the sense of isolation one encounters in the more still, shadowy compositions of the work. More decisively, a series of low-angle, upward-vertical camera movements (which echo the one Brakhage enacted earlier in The Wonder Ring) within the outdoor settings of a forest and a grassy lawn convey a profound sense of search. Though the meanings of a work as radically open as Anticipation of the Night ultimately belong to the individual viewer (and Brakhage likely would have agreed), these upward-vertical camera movements, which begins at ground-level and end by looking upward at the intense light of the sun pouring into the camera lens through the tree branches above, may be imaginatively interpreted as a kind of lifting, an action which implies an attempt to overcome some obstacle or to escape from some low place or position. The way these compositions embrace beauty and forms of movement at times seems to narrate an attempt to overcome despair rather than accept it, and they imbue the work with a sense of struggle, a kind of war between two contrasting emotive forces.

Even more than in The Wonder Ring and Window Water Baby Moving, light seems to take on the status of primary subject in much of Anticipation of the Night: in the sequences described above, the directionality of camera movement seems to be motivated above all by the position of luminous objects, rather than objects which belong to the physical world. The way that Brakhage’s camera-eye appears to be drawn toward this light, moving toward it in violent, labored, or haphazard ways like a moth toward a flame, instills much of the work with a quality of seeking, a search for light within vast regions of visual and emotional darkness. In this regard, the use of light in Anticipation of the Night might be said to transgress the metonymic quality seen in earlier films, moving instead toward a kind of metaphoric status. Here, light itself finally becomes allowed to occupy a position of equal importance within the work’s organization and construction as the latent meanings generated by the film’s protagonist and drama are, and in fact seems to be placed into a kind of dialectical relation with those elements, elements which Brakhage himself will soon be moving away from in his work.

And what does this metaphor describe, exactly? Camper has provocatively called Anticipation of the Night a “testament to the failure of imaginative seeing”, and this profound sense of failure haunting the work can of course be related most obviously to the act of suicide that ends the film, which Brakhage narrates by showing the protagonist’s hand tying a noose to the branch of a tree, followed by the silhouette of his head and neck hanging from it for several moments as his shadow writhes in a kind of struggle. The final event one sees in the film, though, is not precisely this despairing act, but rather an orb of orange light flickering and then enveloping the dim gray-blue sky, expanding in size and eventually turning to a blistering white as it overshadows our view of the protagonist’s struggle. Given the importance that luminous objects have assumed throughout the work’s duration, this final detail should not be seen as trivial, and it gives the ending a different quality than a more conventional cut to black would. Brakhage seems to be, in some mysterious and submerged way, metaphorically relating the protagonist’s “failure” with an inability to properly see light and to properly heed the beauty that its illumination provides, and the way that light finally outlasts this anguished struggle residing in the material world (a struggle which has informed much of the body of the film) appears to be an illustration of this idea, a notion which can also be seen as a statement of artistic intent informing the rest of Brakhage’s cinema. Abstraction finally triumphs over representation at the end of Anticipation of the Night, which at a mere 42 minutes begins to acquire the contours of an epic in the grand scope of its ambitious construction and in the depth of its ideas.

Stan Brakhage, Anticipation of the Night (1958)

If Anticipation of the Night has often been (rightly) regarded as a work of central importance in Brakhage’s cinema and in his artistic development, this is partly because the filmmaker’s subsequent films seem to have in some sense absorbed the reconciliation of the struggle he enacts in this work and the lessons that this experience provided. Brakhage himself spoke about this through the lens of leaving behind the influence of drama: “I would say I grew very quickly as a film artist once I got rid of drama as a prime source of inspiration. I began to feel all history, all life, all that I would have as material with which to work, would have to come from the inside of me out rather than as some form imposed from the outside in.” But it isn’t merely this changing attitude toward drama and external influence which makes the film a watershed for the filmmaker; it can also be felt in the way the film represents both a culmination and a next step within an evolving approach toward light and abstraction in his cinema. The transformation from light as a source of metonymic power in earlier works like The Wonder Ring into one of metaphoric power in Anticipation of the Night eventually leads to more hermetic experiments which examine the potentiality of luminous abstraction on its own terms.

Subsequent works like The Riddle of Lumen and Sol (1974) seem to display an interest in exploring and contrasting different levels of abstraction for their own sake and in a way which does not possess any kind of fictive or metaphoric relation to the material objects being filmed. This general plunge toward abstraction culminates in Brakhage’s late films, the majority of which were hand-painted and have no (or only a very tangential) relation to notions of the photographic or the indexical. Revisiting early works like The Wonder Ring, Window Water Baby Moving, and Anticipation of the Night remains a thrilling experience, not only because watching these films represents an opportunity to witness the filmmaker’s development in action, but also because one can see in them a more direct or causal relationship between physical and abstract elements of the image, a relationship which would become more difficult to define in the latter part of Brakhage’s career.

Bibliography

Camper, Fred. “Program Notes on Brakhage”. fredcamper.com, https://www.fredcamper.com/Brakhage/FC.html, 20 April 2003.

Note: My citation of Camper throughout the first paragraph of this essay combines certain comments that the critic makes in the piece cited above, which was written for a 2003 Brakhage program in Ithaca, NY and has been reproduced on his website, as well as comments he made at another Brakhage program which took place at the Gene Siskel Film Center on 2 December 2023, entitled “Stan Brakhage: Imagination and Perception”, which I attended and which to my knowledge has not been published in written form.

Brakhage, Stan. “From Metaphors on Vision (USA, 1963)”. Film Manifestos and Global Cinema Cultures: A Critical Anthology, edited by Scott MacKenzie, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014, pp. 62-69.

Adams, Sitney P. “The Lyrical Film”. Visionary Film: the American avant-garde 1943-2000. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Camper, Fred. “A Review of Brakhage’s Last Films”. Chicago Reader, fredcamper.com, https://www.fredcamper.com/Film/Brakhage3.html, 16 May 2003.