Vincent Czyz, Adrift in a Vanishing City, Rain Mountain Press, New York City 2015

Not to find one’s way in a city may well be uninteresting and banal. It requires ignorance—nothing more. But to lose oneself in a city—as one loses oneself in a forest—that calls for quite a different schooling.

—Walter Benjamin

“Nothing is careless about this writing at all,” declares Samuel R. Delany in the introduction to Vincent Czyz’s Adrift in a Vanishing City, a robust collection of stories, each as ferociously poetic as they are distinctly structured.

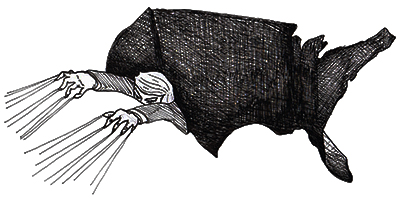

Admittedly, though, “structured” doesn’t capture the sensitivity of these compositions. If, for instance, sixty percent of contemporary American short fiction is tract housing, and thirty-five percent brazenly Bauhausian, aimed only at revealing literary performance, Czyz’s Adrift is working in that same narrow space where we locate, say, the mature spirit of Frank Lloyd Wright. In other words, Adrift is organically architectured, its stories sprung not from tired crafting tricks or radically experimental plotting, but from a seasoned yearning for harmonization between language, landscape, and reader.

When Delany says, “Nothing is careless,” he does not mean this book is mechanically meticulous, but replete with caring. Character, conflict, dialogue, POV—these elements grow from Czyz’s lush and unabashed devotion to imagery, to the sacred act of painting Place.

She thinks of him during long winter nights silent and clear as a sky full of constellations (he has shown her the place where her sign rises, how his is framed at certain times of the year by her bedroom window). The ice jackets on tree branches, on overgrown grass, shiver and crinkle with the slightest breeze, tinkle like chimes. During the season of changing colors with its misty-breathed mornings, she wonders who is waking up next to him. One of those free-love girls with big tits and too much mascara he likes so much most likely, shaking her can all over the bar he met her in.

Annie Proulx said, “If you get the landscape right, the story will come from the landscape.” Read her prose as a testimony to this narratival phenomenology, the might of her murals, their absolute authority, how Place demands character conformity. In Proulx’s narratives a story is weather roiling lyrically across the hard truth of universal human nature, and Czyz writes with this same wisdom, though minus, I think, Proulx’s cynical grit.

I assert this contrast as caveat, because the cynical reader will struggle with the level of sincerity needed to read the whole of Adrift. The book boasts rampant humor and wit, and tremendous moments of graphic action, and strenuous, existentialist discussions of disillusionment, but it requires of its reader an open-hearted, even mystical, earnestness. It demands we remember that how we read is of utmost importance, that reading can and must be an act of caring—that reading teaches how to care about relationships, communities, contexts, and the unfathomable power of words (which, in this political climate, with so much populist rhetoric about “common sense” and “straight talk”, with a new president who, in a July 2016 The Washington Post story, is quoted as saying, “I never have [had time to read]. I’m always busy doing a lot,” is a message that can’t be overstated).

Of course, humans do a great deal of things with their bodies without doing much with their minds, and, sadly, even less with their hearts. But in the pages of Adrift, humans inhabit worlds wherein physicality is born of emotionality—not the other way around—and where metaphor is not a utility of the human, but the human, in all its fragile agency, is realized solely through metaphor.

And on those sweaty Kansas evenings her hair just won’t stay, a hot orange moon big over the fields, crickets rub against each other’s solitude and she misses him most.

From the opening story, “Zee Gee and the Blue Jean Baby Queen”—the Midwestern evening sweats as a body sweats, as she must sweat, which is physiological and emotive. We feel the evening’s paradoxical density, the dirge of blackening day and the fiery lift of night. Night, however, does not fall, but hovers. Night is cypher, where sun is to eye as moon is to hollow socket, and she, observer, sees but is not seen, her gaze eternally unreturned. While, also, the moon is her hair, red, a monolithic passion, and the fields, in all their plurality, are the strands gone feral, reaching out as thoughts untethered. Evening, when the mind turns from prosaic cares to mythic ones, when metaphor is the only way to navigate desire. The world around her, in every way, detaching, and hers is a loneliness too big for one human body. Her loneliness is something stared at but impossible to confront in all its totality: love—

As chafing crickets magnify this truth. Their rub the orchestra of desire’s irony—how it is always there and always not. Czyz reminds us that there is something hyper-ritualistic about crickets serenading a rising moon, but ritualistic only in the way the moon is ritualistic, which is to say as a projection of a certainty that can’t be grasped. The crickets absorb this projection, for they, too, are living and dying things. Crickets playing the friction of their own bodies, but all at once, and, as such, much bigger than they will ever be in their singular insignificance….

Or how, in this same way, the crickets are her little city, Pittsburg, Kansas, the dark center of America, its great silence that isn’t a silence. The crickets are a pulse, a yearn, that is, yet cannot, be isolated. They are home in the way home is never where we left it. Crickets give you their sound when you don’t seek them out, but should you look, you’ll never locate, and, in doing so, destroy all that beautiful noise of human ache, how it reaches out but is forever unable to grasp and arrest, to denote some clear division between need and plea, here and there, then and now.

Possibly I took that close reading too far, but one can’t help it when tackling Adrift. The book not only undertakes, but stimulates, the grandest poetic speculation, each paragraph a million little emotional pilgrimages. In the second story, “Overhead, Like Orion”, we encounter the him of her missing.

From a few hotel stories up, this town don’t look like much, a little cross-hatchin a tar streets an’ concrete sidewalks on the plains, could be swept away by one a those summer thunderstorms, angry clouds comin in like a dark billowin herd driven by wind riders, winds up takin up the whole sky, lightning spiderin across a stretch a black big as half the state, but town’s still here, the dust a worn out years blown down Broad…

Unlike her, so close in third-person omniscient, we meet him from the distance of the unreliable first-person, the center of his own language, his own faulty idea of who it is that he tells himself he is. He has returned, yet again, to the heartland, to his hometown, which is her reality, not, he tells himself, his. He is looking down at the lack he sees, the fragility he wants to see. His are the eyes of one who has gone and returned, who has compared and sought and experienced a glut of Other-ness. Now this Kansan town—his past—is just sketch and façade, somehow, to him, less material than the weather.

Or, again, that’s how he wants it to be. He affiliates his own perspective with the storms and the wind and the lightning—but, within his own metaphor he’s confronted with a veracity much more sweeping than his own nomadic vision: the town, his past, his roots, her, these things are resilient, more than he hopes them to be, more than he’ll ever be. He thinks,

Man’s always been hollow, since the day a goddess breathed him alive … just solid enough to build cities. Me, just empty enough for dust storms to kick up. Not something to wait out, but something that wants out.

Zirque’s his name. The perpetual prodigal of savant drawl, only back in body, though, back in Pittsburgh, Kansas, but still dreaming Berlin and New York, Paris and Hollywood. Zirque, the book’s protagonist—not always by name, but certainly by archetype—embodies the troubled profundity of what one individual caring for another means. Here is the tethered drifter, the devoted philanderer, the master jack-of-all-trades. Here is erudite redneck, the world-wise American.

Zirque is our central character who’s only central in that he’s the greatest hole in the text—haunting each story in the collection either directly or indirectly. He’s the archetype and its yawning interior. In this way, every story in the collection gestures at the title. To be adrift in a vanishing city is to be a fluid being in a maze of watery projections. But these projections must be treated as concrete, for they are what transforms the flimsy to the collective, to the shared, to the meaningful. Cities represents the human’s attempt to turn caring into something tangible. They are built by relationship in order to house and protect relationship. There are numerous cities in this book—large and small, ancient and new, vibrant and destroyed—but they are all the same; they are the human’s need to ardently invest and the human’s inability to create something that might actually eternalize that need.

With “Cada Edad Tiene Su Encanto”, third in the collection, the reader’s progress with the two lovers and their small-town hearts seems startlingly aborted. Czyz whisks us to an entropic, Mexico City hotel, and introduces yet another narrator, this in second-person. Here is a voice akin to the controversial journalism of the wildly talented Joseph Mitchell, that of the wizened biographer whose passion for engaging a subject inevitably collapses subject and object, observer and observed. This narratival voice paints for us a portrait of Eduardo, but, like the “editorial you” that, when you read it and occupy it, is not editorial at all, Eduardo is, simultaneously, glorious phantom and plaintive human.

Resting his creaky back against a chair in the lobby, Eduardo must have directed a comment at the aging manager who steps from past to present, past to present and loses a frame of motion, the continuity, in between—

For twelve years Eduardo’s haunted the decrepit El National, living out of one of the forgotten room’s in this once-regal hotel:

You will not be able, even in the pliable realm of imagination, to restore the balding carpets in the hallway, the dulled paint (un-evenly done in the first place) in need of dusting and a fresh coat, the water-stained ceilings, the bare-bulb lighting, the brownish tapwater (The Victorian clock with wrought-iron hands has stopped in the lobby but rust marches on in the pipes). Time is a measureless matter of daylight filtering through the exhaust-fume sky through yellowish shades brittle as old newspaper.

You, reader, will not be able, but you are compelled by your rationale to try, to construct (like the reporter/narrator) from the way things are the way things were. But this sort of calculus is impossible in the realm of imagination, because imagination has its own principles of measurement—those of the heart, not the mind. In the book’s Afterword, Czyz writes,

Unlike most works of fiction, which begin with a familiar disclaimer, this one ends with more or less the opposite intent. The fact is, many of the characters closely resemble persons both living and dead … Eduardo Lerma, whom I had met in Mexico City, died well before the collection was even published. I learned of his death via a long-distance phone call I had made to El Congreso (the real name of the hotel where he had lived). I took the loss all the harder, knowing Eduardo would never read about himself or ever realize how much he’d been in my thoughts in the years since I’d met him.

In other words, if there is a moral—or, no, a revelation—that runs through this collection, it might be: to care is to vanish. Ah, but also to expand. Because with caring, Czyz shows us, there is no middle ground … there is just ground. You can’t not think of somebody; they either exist in your consciousness or they don’t. You either care or you don’t—it’s not an intellectual choice; it’s visceral, automatic, and transcends petty categories of logical awareness, of acceptance and rejection, or, say, fiction or nonfiction.

Human biology is hard-wired to care about its physical well-being, the pragmatics of survival, but what undermines this intuition is an even greater caring, an absurd, mythological, blind-groping species of caring, the ineffable tenor of caring—love, truth, heartache and the search for validation of one’s existence in the existence of the Other.

“Nothing … careless … at all.” To not be careless is to be attentive. It is to be actively alert to the energy of living things in a living world. Delany wants to convey Czyz’s remarkable ability to hear beyond what he’s writing, to tune into more and different and other tributaries that a given story unearth:

Some nights in drizzle more like drifting mist Pap saw her, long read hair shimmery with it, smeared with light from the streetlamps, and up a block a couple arm in arm, and in some other city maybe Zee Gee was thinking of her, the falling mist in her was pain. No shape, it found its way everywhere, seeped through her, rubbed off on you when you took her hand, want and need and sadness that smelled of her.

In story four, “The Night Crawler”, our narrator is both inside and outside of Pap, this town drunk, this sorriest soul in Podunk, Kansas. Our narrator watches Pap watching Rae Anne, watching through other eyes, story eyes, the eyes of another man, Zirque—or Zee Gee, her absent lover. Pap becoming narrator then, through his yearning as universal of all characters’ yearning, authority dispersed, slipping about with the sound of the scene, giving renewed focus to the how—for who is it that smears the light and smells the sadness? And how, when she or he, or you the reader, is a block or a continent away, or a book, away, yet can still reach out and take a hand?

“…a particular aesthetic consciousness…” Delany calls Czyz technique, but the same by any other name, for Czyz’s writing offers up his reader to the consciousness of each story. The looping trajectory of desire between two people becomes the desire between all people in all places at all times, and, more fundamentally, the irrationality of desire within every person.

As Zirque develops as character and, more essentially, as theme, we see his growing discomfort with how comfortable he has become running away from feeling comfortable. This, I believe, is Czyz decisive critique of the postmodern impulse. These love stories—and they are all, clearly, love stories—don’t seek to deconstruct the notion of love to some cold, plastic irony, but re-assert love as something that both infuses and transcends the finite logics of literature. For even as these stories sprawl they vanish, even as they roam and carve, as plotlines wheel off on their own orbits, so too do they come clawing back together. Reading deeper and deeper (or over and under), the sequential melds with the synchronic.

In a way, this can make for jarring transitions between each work, at least for readers who don’t pause at each formal ending, but who feel a need to—especially if the next tale is an obvious continuance of the same narratival world—scout for some manner of assurance that the voice nurtured in one’s skull will survive and grow comfortable. For to grow comfortable even with earnest is to grow careless and destroy that earnestness (you can’t go looking for the crickets). It is a merging from relationship (which is synchronized conflict and contained discord) into singularity, into unity. To grow comfortable reading is to vanish into the book as unimaginative lovers vanish into one another, having lost the diverse foci that engaged them in the beginning.

So Adrift makes voyeurism impossible. There is no fine point to how this impossibility works; I can only say, again, that the reader’s earnestness is demanded, endlessly.

Blamin my restlessness on anything that can’t get up to argue the point, I take the way of greatest desire, whatever the moment dangles before me. A blue print drawn up by expectation, most often endin in disappointment.

The point comes later, the argument in the form of memory, contemplation, in the wake of damage done. We subvert logic, we break our bodies, we carouse and suicide, all in order to care and not care. Zirque’s body is a living testament—twisted and tooth-broke from rodeo and car-wrecking and dope deals gone south. Attempting to live fully in the present, Zirque is even more pronouncedly cursed by desire’s relationship to disappointment. He wants to care about not caring, but to do this he can’t pause to contemplate. The minute he does pause, return, hold—that is to say, in the moments his memories, or others’ memories of him—turn from action to assessment, all the poetry and the romance, turns the ugly shade of damaged relationship. Zirque’s homegrown beloved, Rae Ann, says he’s broke her heart a hundred and fifty times at least, that he’s does so each time he leaves. Which stirs up the question of whether or not she’s the one breaking her own heart—if the human is capable of not breaking its own heart. Zirque tells her,

The heart ain’t a muscle but a place, where you either live, or you don’t.

And then he says,

But I always come back. I got a chronic case of claustrophobia that’ll turn terminal if I don’t get away from time to time. You can’t call it id or superego, it’s an illness a the spirit around since the time a the ziggurat-builders in Sumer.

While two woman want to breach his city walls, waiting and not waiting in their own ways. Two women, two overlapping landscapes, caring for Zirque. Rae Ann, the high school sweetheart, caring blatantly, and Veronique, the Parisian sophisticate, caring clandestinely, almost coyly. For Zirque’s carelessness inspires their caring. Here is the love-triangle trope re-drawn as a circle, until chasing and chased are indistinct, passion because hopelessly timeless, held together by periphery but empty in at its core.

And what is to be done with those of us who have an aching for a myth to support our lives, a backbone, an Yggdrasil whose roots curl like a fist around our trouble hearts, whose leafy branches disappear in the strange horizon where vision blends with the sky lording over it, the pale moon and occasion lumps of burning rock-iron-copper angels who fall through it, gather at our feet as dust that has traveled light years to be stepped on and forgotten except for that one phosphorescent moment when we knew to make a wish before it was already too late.

So Veronique muses, which begins as a question, but, in the spirit of Czyz’s entire collection, bursts free of its directive, reaching out as leafy branches, in the same way Rae Ann’s hair strands were strewn below that implausible moon. For to assume any serious answer actually exists is to deny, in the first place, the ache for myth.

Though then we have Zabere, the writer character, the essayist, or attempter of answers. Zabere is Veronique’s best friend, removed from the love triangle by his homosexuality, but immersed in the love circle in the way caring operates (his sexuality a displacement, but, somehow, also a relegation to the status of not-so-impartial commentator), meaning how we will read other lovers, and take our sides, and scribble our interpretations, as if our fleeting analyses have any bearing on the reality we are attempting to document.

Zabere is the reader collapsed into writer, scratching away in his journal, the café poet attempting to catalog the now even as it evaporates into ink:

How strange what separates us from one another is so easily snapped broken breached and yet so rarely. We prefer to go on with our isolation, like dots on a balloon spreading ever farther apart as the space around us keeps getting bigger, more babies are born, more cities are built, fewer loves form over the distances

—

From moment to moment, cities vanish and newborn cities sprout in their stead. One can never walk the same street twice, or walk the same street with another person. Same goes for the reader: one can never return to the beginning of a sentence, a story, a book, and find it in the condition one left it. Same goes for reading, one can never read the story the writer has written, we can only tell ourselves we have to protect from that which might, as Zabere points out, snap too easily.

With this review, I have trekked deep into the book. Zabere’s story, “Bring on the Night,” is number seven in the collection of nine. It marks Adrift’s most distinct swing toward formal innovation, interspersing journal entries written in the “now” of the story’s “now”, which draws attention to the way humans seem most desperate to attempt frames for those things we feel unframeable, and, in so doing—like photographers feverishly snapping photos of the very moments they’re missing—try to protect our sublime sense of caring from getting out of hand. And this seventh-story shift to formal metafiction is heightened in the final two stories, as if the reader has earned an earnestness capable of, now, revisiting the postmodern without its comfortable armor of irony.

“Nothing … careless … at all.” Delany strings together these hyperbolic absolutes as not mere observation or warning or praising—he’s doing all of these things, yes—but mostly he’s reminding us how we need writers like Czyz; we need writers who will challenge us to care not reasonably, but with every ounce of our emotional might.